P62 is a versatile protein involved in the delicate balance between cell death and survival, which is fundamental for cell fate decision in the context of both cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. As an autophagy adaptor, p62 recognizes polyubiquitin chains and interacts with LC3, thereby targeting the selected cargo to the autophagosome with consequent autophagic degradation. Beside this function, p62 behaves as an interactive hub in multiple signalling including those mediated by Nrf2, NF-κB, caspase-8, and mTORC1. The protein is thus crucial for the control of oxidative stress, inflammation and cell survival, apoptosis, and metabolic reprogramming, respectively. As a multifunctional protein, p62 falls into the category of those factors that can exert opposite roles in the cells. Chronic p62 accumulation was found in many types of tumors as well as in stress granules present in different forms of neurodegenerative diseases. However, the protein seems to have a Janus behaviour since it may also serve protective functions against tumorigenesis or neurodegeneration.

- p62

- autophagy

- apoptosis

- cancer

- neurodegenerative diseases

1. Introduction

P62 is a multifunctional protein that was originally identified as a component of the sequestosome, a cytoplasmic structure which serves as a storage place for ubiquitinated proteins [1]. The p62 encoding gene was then isolated and termed sequestosome 1 (SQSTM1). The protein was the first adaptor involved in selective autophagy identified in mammals[2]. Studies on selective protein degradation reveal a crucial role of p62 in autophagic digestion of poly-ubiquitinated protein cargo. During the early steps of autophagosome formation, a dimeric form of p62 is phosphorylated in Ser407 by Atg1/ULK1 kinase, one of the upstream ATG gene products that trigger the autophagic flux. This phosphorylation destabilizes the p62 dimer and renders the protein prone to undergo subsequent phosphorylation by other kinases (casein kinase2 or TANK-binding kinase1) to increase the binding affinity of p62 for ubiquitin chains[3]. It is well known that p62 can preferentially bind to Lys63 ubiquitin chains and this might represent a subtle level of regulation during selective autophagy[4].

Following binding to ubiquitinated proteins, p62 undergoes oligomerization and interacts with the autophagosomal membrane protein LC3, thus delivering the cargo aggregates to the autophagosome[5]. LC3 exerts multiple roles in autophagy including membrane fusion, cargo selection and autophagosome mobilization. LC3/p62 interaction is indispensable for autophagic degradation of polyubiquitinated cargo. Moreover, the same p62 becomes degraded by the autophagosome, which makes the protein a marker to monitor the autophagic flux. Indeed, a precocious increase in p62 cellular levels is usually observed during autophagy execution, and a subsequent decrease, due to autophagic degradation of the protein, occurs later when autophagy is completed[6][7].

As a multifunctional protein, p62 not only takes part in selective autophagy, but also interacts with many factors that play important roles in determining cell fate. p62 behaves indeed as a signalling hub and can be considered a main regulator of key pathways including the nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2/Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Nrf2/Keap1) oxidative defense system, NF-kB mediated-inflammation and pro-survival response, mTORC1 related nutrient sensing, and caspase-8- mediated apoptosis[8][9][10][11]. Due to its versatile behaviour and capability of recruiting diverse binding partners to influence many cellular processes, p62 is clearly involved in important diseases including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders[12][13] exerting a Janus role.

2. P62 Structure, Post-translational Modifications and interactors

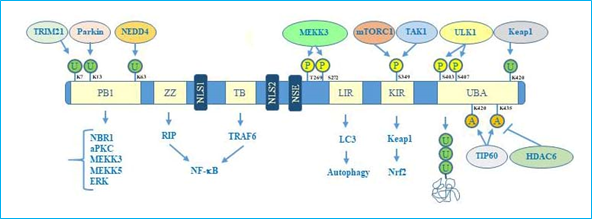

Concerning the structure, human p62 exists in two protein isoforms that originate by alternative splicing of three mRNA variants. p62 mRNA variant 1 encodes the full length 440-aa protein. The other two mRNA variants (2 and 3) share the same coding sequence but differ in their 5′UTR regions. Both these variants encode p62 isoform 2, which is 84 amino acids shorter than p62 isoform 1 at the N terminus. While the precise function of this isoform remains unknown, the full length p62 is widely expressed and represents the predominant one[14]. The full length p62 protein structure, including domains and multiple interactors, is reported in Figure 1.

Figure 1. p62 structure, functional domains, post-translational modifications, and interactors. In particular, the figure shows Phox/Bem1p (PB1) domain, which is important for p62 oligomerization, with indicated ubiquitination sites, relative ubiquitinating enzymes (Trim21, parkin, NEDD4) and interactors (NBR1, atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), MEKK3, MEKK5, ERK); Zinc finger ZZ and TRAF bindingTB domains necessary for interaction with receptor interacting protein (RIP) and TRAF6, respectively, to activate NF-κB signalling; nuclear localization sequences (NLS1 and NLS2), and nuclear export sequence (NES) which account for nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of p62; LYR and Keap1-interacting region (KIR) domains that interact with LC3 and Keap1 respectively to promote selective autophagy and nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like 2 (Nrf2)-mediated signalling. Ubiquitin associated (UBA) domain is fundamental for recognition of poly-ubiquitinated cargo during selective autophagy. Post-translational modification sites including phosphorylation, acetylation, and ubiquitination together with the respective regulative enzymes (MEKK3, mTORC1, TAK1, Keap1, Tip60, HDAC6) are also indicated.

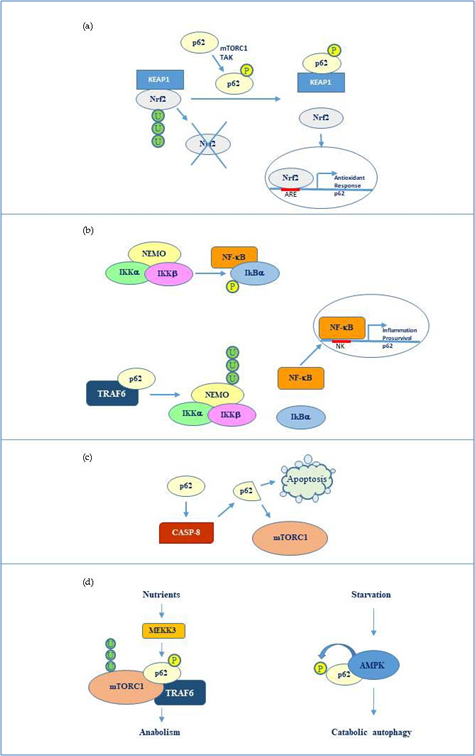

Overall, the flexible structure of p62 and the fine regulation due to post translational changes makes this protein a versatile interactor and a key factor regulating diverse cellular processes by cooperating with multiple specific partners. The main p62 interactors are indicated in Fig 2.

Figure 2. p62 molecular interactors and relative signalling. (a) Phosphorylated p62 (Ser349) activates Nrf2-mediated oxidative response and cell survival by sequestering Keap1. p62 expression is then activated by Nrf2 in an amplification loop. (b) p62 promotes NEMO ubiquitination via TRAF6 favouring NF-κB activation and consequent transcription of genes involved in inflammation and pro-survival response. NF-κB also induces the same p62 expression. (c) p62 stimulates caspase-8 which in turns cleaves p62 thus promoting apoptosis or mTORC1-mediated nutrient sensing. (d) mTORC1 modulation by p62 via TRAF6 and stimulation of anabolism in the presence of nutrients and AMP kinase mediated p62 phosphorylation during starvation and consequent catabolic autophagy.

3. OncoJanus Role of p62

3. OncoJanus Role of p62

The different properties of p62 and diversified roles deriving from the broad spectrum of interactors make the protein a double edged sword in cancer. A number of papers supports an oncogenic role of p62 in a wide variety of human cancers[12]. Accumulation of p62 has been found in several forms of tumors including hepatocarcinoma, breast, lung, gastric, colon, and ovarian cancers[15][16][17][18]. Increasing evidence demonstrates that abnormal expression of p62 is associated with malignancy in most cases. Notably, p62 knockout or knockdown have been shown to abrogate tumor growth in different cancer models[19][20]. In such a way, p62 may be considered as an oncogene. From a molecular point of view, given that p62 abundance may favour pro-survival tumor-associated autophagy, increased activity of p62 was also correlated with increased phosphorylation. In particular, the phosphorylated form of p62 in Ser349 leads to persistent activation of Nrf2 signalling promoting cell survival and consequent tumor growth[21].

The other side of the coin is that p62 can exert a protective function against tumorigenesis, acting in tumor microenvironment. For instance, p62 levels were found to be reduced in the stroma of several tumors and loss of p62 in the tumor microenvironment resulted in increased tumorigenesis[22]. In the scenario of tumor microenvironment and communication of tumor cells with other cell types, a relevant function of p62 has been identified in tumor surrounding macrophages. Induction of p62 through NF-κB in macrophages serves to limit the release of cytokines, such as IL-1b, and consequent inflammation, which is likely to promote tumor survival and growth[23]. Some evidences indicate that p62 preserves macrophage homeostasis and reduces their oncogenic potential[24].

Intriguingly, p62 has also been shown to exert an anti-tumor function within cancer cells. For instance, at the nuclear level p62 can control DNA damage through inhibition of histone H2A ubiquitination, thus affecting DNA repair and increasing the sensitivity of tumor cells to radiation[25]. In such a perspective, high levels of p62 can even represent an advantage for cancer therapy.

It is relevant that the antitumor function of p62 is related to its nuclear localization. In this regard, it has been shown that low nuclear level of p62 was associated with aggressive clinic pathologic features and unfavorable prognosis of oral squamous cell carcinoma[26].

Taken together, all these findings strongly support the dual role of p62 in cancer. If on the one hand we consider p62 as an oncogene because of its overexpression in many tumors, on the other hand this condition

may be strategically used against cancer to improve the therapeutic efficacy.

4. NeuroJanus Role of p62

Given the role of p62 in selective autophagy and implications in regulating the balance between cell death and survival, it is not surprising that this multifunctional protein is also involved in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Due to its functional plasticity, p62 serves indeed as a signalling hub for multiple pathways implicated in neurodegeneration. P62 may be neuroprotective since it promotes pro-survival autophagy against various types of neuronal stresses or it may be neurotoxic when overexpressed or deregulated. Moreover, many evidences indicate that aberrant p62 is found in association with specific aggregates that are typical of different neurodegenerative diseases[13][27]. For instance, low expression of p62 has been found in many forms of Alzheimer Disease (AD) and p62 loss of function has been shown to result in Aβ accumulation, tau hyperphosphorylation, and consequent neurodegeneration[28][29]. Interestingly, overexpression of p62 was able to rescue cognitive deficit in transgenic AD mice models. p62 protective role is most likely correlated with its capability of promoting the degradation of misfolded protein through the autophagy pathway. On the other hand, increased autophagy can occur during Alzheimer development and its deregulation may cause neuronal damage. For instance, in some cases, mitophagy, the selective autophagic degradation of mitochondria involving p62, was found excessively intensified in neurons leading to synaptic deterioration and axon degeneration[27].

P62 has also an important role in the prevention of dopaminergic neurodegeneration implicated in Parkinson Disease (PD)[30]. Notably, evidence has been provided that autophagy failure can lead to p62 association with α-synuclein accumulation into Lewy bodies[31]. In this context, an important function is exerted by parkin, the product of PARK2 gene, which serves a protective function in dopaminergic neurons. Parkin has been shown to ubiquitinate p62, thus promoting its proteasomal degradation. Through the control of p62 levels, parkin, together with the mitochondrial factor Pink1, is also associated with p62-dependent mitophagy. Parkin loss of function results in p62 accumulation and association to Lewy bodies. Deregulation of Pink1/parkin/p62 pathway has been associated to increased vulnerability of neuronal cells toward PD development[32]. Overall, if on one hand mitophagy failure leads to p62 accumulation and association with α-synuclein and PD pathogenesis, on the other hand, p62 is fundamental together with parkin and Pink1 to maintain neuronal homeostasis and survival.

Finally, many evidences indicate that p62 is also involved in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), a progressive and fatal neurodegenerative disease, which is caused by the gradual depletion of motor neurons in the cerebral cortex, the brain stem or the spinal cord[33]. One common aspect of different ALS forms is the aggregation of insoluble proteins within cells. In particular, intrinsically disordered proteins such as DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) and fused in sarcoma (FUS) are frequently associated to the pathogenic aggregates within motor neurons of ALS patients[34]. A minor percentage of patients (about 20%) have accumulations of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), a key antioxidant enzyme involved in toxic superoxide radicals disposal within the cell[35]. Accumulation of such proteins in amorphous aggregates is due to genetic mutations in their encoding genes or aberrant expression of their inactive forms. Most of these inclusions have been shown to be ubiquitin-immunoreactive and in many cases, they contain mutated p62. Autophagy impairment or p62 loss of function may therefore contribute in ALS pathogenesis[36]. On the other hand, functional modulation of p62 can switch toward neurodegeneration. For instance, p62 phosphorylation at Ser403 increased upon TDP43 overexpression in neuronal cells and this was correlated with accumulation of insoluble poly-ubiquitinated proteins and neurotoxicity[37]. This evidence confirms that p62 can either suppress or promote neurodegeneration depending on particular circumstances, cell context and interactive networks.

5. Conclusions

Conclusions

Biochemical complexity is a hallmark of multi-factorial diseases, including cancer and neurodegenerative disorders. In a wide and intricate molecular scenario, it is not easy to strictly classify a factor as a positive or negative regulator in the pathogenesis and disease development. P62 perfectly fits the feature of a double-faced protein depending on cell context, interacting networks, expression levels, and regulative post-translational modifications. If we can consider p62 a “benefactor” when it contributes to protect the cells from tumorigenesis or neurodegeneration, we have to consider it a “malefactor” when it is de-regulated or overexpressed thus causing the opposite effects. Discriminating such behaviour becomes important to understand the molecular basis of the above-mentioned diseases and to perform appropriate targeted therapies.

References

- Jaekyoon Shin; P62 and the sequestosome, a novel mechanism for protein metabolism.. Archives of Pharmacal Research 1998, 21, 629-633, 10.1007/bf02976748.

- Trond Lamark; Steingrim Svenning; Terje Johansen; Regulation of selective autophagy: the p62/SQSTM1 paradigm. Essays in Biochemistry 2017, 61, 609-624, 10.1042/ebc20170035.

- Junghyun Lim; M. Lenard Lachenmayer; Shuai Wu; Wenchao Liu; Mondira Kundu; Rong Wang; Masaaki Komatsu; Young J. Oh; Yanxiang Zhao; Zhenyu Yue; et al. Proteotoxic Stress Induces Phosphorylation of p62/SQSTM1 by ULK1 to Regulate Selective Autophagic Clearance of Protein Aggregates. PLoS Genetics 2015, 11, e1004987, 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004987.

- Daxiao Sun; Rongbo Wu; Jingxiang Zheng; Pilong Li; Li Yu; Polyubiquitin chain-induced p62 phase separation drives autophagic cargo segregation. Cell Research 2018, 28, 405-415, 10.1038/s41422-018-0017-7.

- Rodolfo Ciuffa; Trond Lamark; Abul Tarafder; Audrey Guesdon; Sofia Rybina; Wim J. H. Hagen; Terje Johansen; Carsten Sachse; The Selective Autophagy Receptor p62 Forms a Flexible Filamentous Helical Scaffold. Cell Reports 2015, 11, 748-758, 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.03.062.

- Claudia Pellerito; Sonia Emanuele; Francesco Ferrante; Adriana Celesia; Michela Giuliano; Tiziana Fiore; Tributyltin(IV) ferulate, a novel synthetic ferulic acid derivative, induces autophagic cell death in colon cancer cells: From chemical synthesis to biochemical effects. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry 2020, 205, 110999, 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2020.110999.

- Sonia Emanuele; Antonietta Notaro; Antonio Palumbo Piccionello; Antonella Maria Maggio; Marianna Lauricella; Antonella D’Anneo; Cesare Cernigliaro; Giuseppe Calvaruso; Michela Giuliano; Sicilian Litchi Fruit Extracts Induce Autophagy versus Apoptosis Switch in Human Colon Cancer Cells. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1490, 10.3390/nu10101490.

- Da Hyun Lee; Jeong Su Park; Yu Seol Lee; Jisu Han; Dong-Kyu Lee; Sung Won Kwon; Dai Hoon Han; Yong-Ho Lee; Soo Han Bae; SQSTM1/p62 activates NFE2L2/NRF2 via ULK1-mediated autophagic KEAP1 degradation and protects mouse liver from lipotoxicity.. Autophagy 2020, 1, 1-25, 10.1080/15548627.2020.1712108.

- Aurélien Schwob; Elodie Teruel; Louise Dubuisson; Florence Lormières; Pauline Verlhac; Yakubu Princely Abudu; Janelle Gauthier; Marie Naoumenko; Fanny-Meï Cloarec-Ung; Mathias Faure; et al.Terje JohansenHélène DutartreRenaud MahieuxChloé Journo SQSTM-1/p62 potentiates HTLV-1 Tax-mediated NF-κB activation through its ubiquitin binding function.. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 16014-17, 10.1038/s41598-019-52408-x.

- Juan F. Linares; Angeles Duran; Tomoko Yajima; Manolis Pasparakis; Jorge Moscat; Maria T. Diaz-Meco; K63 Polyubiquitination and Activation of mTOR by the p62-TRAF6 Complex in Nutrient-Activated Cells. Molecular Cell 2013, 51, 283-296, 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.06.020.

- Xiao‐Yu Yan; Xin‐Ru Zhong; Si‐Hang Yu; Li‐Chao Zhang; Ya‐Nan Liu; Yong Zhang; Liankun Sun; Jing Su; p62 aggregates mediated Caspase 8 activation is responsible for progression of ovarian cancer.. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine 2019, 23, 4030-4042, 10.1111/jcmm.14288.

- Ariful Islam; Mopa Alina Sooro; Pinghu Zhang‡; Autophagic Regulation of p62 is Critical for Cancer Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1405, 10.3390/ijms19051405.

- Shifan Ma; Insiya Y. Attarwala; Xiang-Qun Xie; SQSTM1/p62: A Potential Target for Neurodegenerative Disease. ACS Chemical Neuroscience 2019, 10, 2094-2114, 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00516.

- Lei Wang; Marisol Cano; James T. Handa; p62 provides dual cytoprotection against oxidative stress in the retinal pigment epithelium. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Cancer 2014, 1843, 1248-1258, 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2014.03.016.

- Atsushi Umemura; Feng He; Koji Taniguchi; Hayato Nakagawa; Shinichiro Yamachika; Joan Font-Burgada; Zhenyu Zhong; Shankar Subramaniam; Sindhu Raghunandan; Angeles Duran; et al.Juan F. LinaresMiguel Reina-CamposShiori UmemuraMark A. ValasekEkihiro SekiKanji YamaguchiKazuhiko KoikeYoshito ItohMaria T. Diaz-MecoJorge MoscatMichael Karin p62, Upregulated during Preneoplasia, Induces Hepatocellular Carcinogenesis by Maintaining Survival of Stressed HCC-Initiating Cells.. Cancer Cell 2016, 29, 935-948, 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.04.006.

- In-Geun Ryoo; Bo-Hyun Choi; Sae-Kwang Ku; Mi-Kyoung Kwak; High CD44 expression mediates p62-associated NFE2L2/NRF2 activation in breast cancer stem cell-like cells: Implications for cancer stem cell resistance. Redox Biology 2018, 17, 246-258, 10.1016/j.redox.2018.04.015.

- Anna M. Schläfli; Olivia Adams; José A. Galván; Mathias Gugger; Spasenija Savic; Lukas Bubendorf; Ralph A. Schmid; Karl-Friedrich Becker; Mario P. Tschan; Rupert Langer; et al.S. Berezowska Prognostic value of the autophagy markers LC3 and p62/SQSTM1 in early-stage non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 39544-39555, 10.18632/oncotarget.9647.

- Cheng Lei; Bing Zhao; Lin Liu; Xiangyue Zeng; Zhen Yu; Xiyan Wang; Expression and clinical significance of p62 protein in colon cancer. Medicine 2020, 99, e18791, 10.1097/md.0000000000018791.

- Huijun Wei; Chenran Wang; Carlo M. Croce; Jun-Lin Guan; p62/SQSTM1 synergizes with autophagy for tumor growth in vivo. Genes & Development 2014, 28, 1204-1216, 10.1101/gad.237354.113.

- Tao Li; Dali Jiang; Kaijie Wu; p62 promotes bladder cancer cell growth by activating KEAP1/NRF2‐dependent antioxidative response. Cancer Science 2020, 111, 1156-1164, 10.1111/cas.14321.

- Yoshinobu Ichimura; Masaaki Komatsu; Activation of p62/SQSTM1–Keap1–Nuclear Factor Erythroid 2-Related Factor 2 Pathway in Cancer. Frontiers in Oncology 2018, 8, 210, 10.3389/fonc.2018.00210.

- Tania Valencia; Ji Young Kim; Shadi Abu-Baker; Jorge Moscat-Pardos; Christopher S. Ahn; Miguel Reina-Campos; Angeles Duran; Elias A. Castilla; Christian M. Metallo; Maria T. Diaz-Meco; et al.Jorge Moscat Metabolic reprogramming of stromal fibroblasts through p62-mTORC1 signaling promotes inflammation and tumorigenesis.. Cancer Cell 2014, 26, 121-135, 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.05.004.

- Zhenyu Zhong; Atsushi Umemura; Elsa Sánchez-López; Shuang Liang; Shabnam Shalapour; Jerry Wong; Feng He; Daniela Boassa; Guy Perkins; Syed Raza Ali; et al.Matthew D. McGeoughMark H. EllismanEkihiro SekiAsa B. GustafssonHal M. HoffmanMaria T. Diaz-MecoJorge MoscatMichael Karin NF-κB Restricts Inflammasome Activation via Elimination of Damaged Mitochondria. Cell 2016, 164, 896-910, 10.1016/j.cell.2015.12.057.

- Rongbin Zhou; Amir S. Yazdi; Philippe Menu; Jurg Tschopp; A role for mitochondria in NLRP3 inflammasome activation. Nature 2010, 469, 221-225, 10.1038/nature09663.

- Yanan Wang; Wei-Guo Zhu; Ying Zhao; Autophagy substrate SQSTM1/p62 regulates chromatin ubiquitination during the DNA damage response. Autophagy 2016, 13, 212-213, 10.1080/15548627.2016.1245262.

- J-L Liu; F-F Chen; J Lung; C-H Lo; F-H Lee; Y-C Lu; C H Hung; Prognostic significance of p62/SQSTM1 subcellular localization and LC3B in oral squamous cell carcinoma. British Journal of Cancer 2014, 111, 944-954, 10.1038/bjc.2014.355.

- Haiying Liu; Chunqiu Dai; Yunlong Fan; Baolin Guo; Keke Ren; Tangna Sun; Wenting Wang; From autophagy to mitophagy: the roles of P62 in neurodegenerative diseases. Journal of Bioenergetics and Biomembranes 2017, 49, 413-422, 10.1007/s10863-017-9727-7.

- Per Nilsson; Misaki Sekiguchi; Takumi Akagi; Shinichi Izumi; Toshihisa Komori; Kelvin Hui; Karin Sörgjerd; Motomasa Tanaka; Takashi Saito; Nobuhisa Iwata; et al.Takaomi C. Saido Autophagy-Related Protein 7 Deficiency in Amyloid β (Aβ) Precursor Protein Transgenic Mice Decreases Aβ in the Multivesicular Bodies and Induces Aβ Accumulation in the Golgi. The American Journal of Pathology 2015, 185, 305-313, 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.10.011.

- Xianhong Zheng; Weiwei Wang; Ruizhi Liu; Honglan Huang; Rihui Zhang; Liankun Sun; Effect of p62 on tau hyperphosphorylation in a rat model of Alzheimer's disease☆. Neural Regeneration Research 2012, 7, 1304-1311, 10.3969/j.issn.1673-5374.2012.17.004.

- Shigeto Sato; Toshiki Uchihara; Takahiro Fukuda; Sachiko Noda; Hiromi Kondo; Shinji Saiki; Masaaki Komatsu; Yasuo Uchiyama; Keiji Tanaka; Nobutaka Hattori; et al. Loss of autophagy in dopaminergic neurons causes Lewy pathology and motor dysfunction in aged mice.. Scientific Reports 2018, 8, 2813, 10.1038/s41598-018-21325-w.

- Yoshihisa Watanabe; Harutsugu Tatebe; Katsutoshi Taguchi; Yasuhisa Endo; Takahiko Tokuda; Toshiki Mizuno; Masanori Nakagawa; Masaki Tanaka; p62/SQSTM1-Dependent Autophagy of Lewy Body-Like α-Synuclein Inclusions. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e52868, 10.1371/journal.pone.0052868.

- Pingping Song; Shanshan Li; Hao Wu; Ruize Gao; Guanhua Rao; Dongmei Wang; Ziheng Chen; Biao Ma; Hongxia Wang; Nan Sui; et al.Haiteng DengZhuohua ZhangTieshan TangZheng TanZehan HanTieyuan LuYushan ZhuYingyu Chen Parkin promotes proteasomal degradation of p62: implication of selective vulnerability of neuronal cells in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Protein & Cell 2016, 7, 114-129, 10.1007/s13238-015-0230-9.

- Senda Ajroud-Driss; Teepu Siddique; Sporadic and hereditary amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease 2015, 1852, 679-684, 10.1016/j.bbadis.2014.08.010.

- Natalia Nowicka; Jakub Juranek; Judyta K. Juranek; Joanna Wojtkiewicz; Risk Factors and Emerging Therapies in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis.. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 20, 2616, 10.3390/ijms20112616.

- Orietta Pansarasa; Matteo Bordoni; Luca Diamanti; Daisy Sproviero; Stella Gagliardi; Cristina Cereda; SOD1 in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: "Ambivalent" Behavior Connected to the Disease.. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1345, 10.3390/ijms19051345.

- Chun T Kwok; Alex Morris; Jacqueline S. De Belleroche; Sequestosome-1 (SQSTM1) sequence variants in ALS cases in the UK: prevalence and coexistence of SQSTM1 mutations in ALS kindred with PDB. European Journal of Human Genetics 2013, 22, 492-496, 10.1038/ejhg.2013.184.

- Shinrye Lee; Yu-Mi Jeon; Sun Joo Cha; SeYeon Kim; Younghwi Kwon; Myungjin Jo; You-Na Jang; Seongsoo Lee; Jaekwang Kim; Sang Ryong Kim; et al.Kea Joo LeeSung Bae LeeKiyoung KimHyung-Jun Kim PTK2/FAK regulates UPS impairment via SQSTM1/p62 phosphorylation in TARDBP/TDP-43 proteinopathies.. Autophagy 2019, 1, 1-17, 10.1080/15548627.2019.1686729.