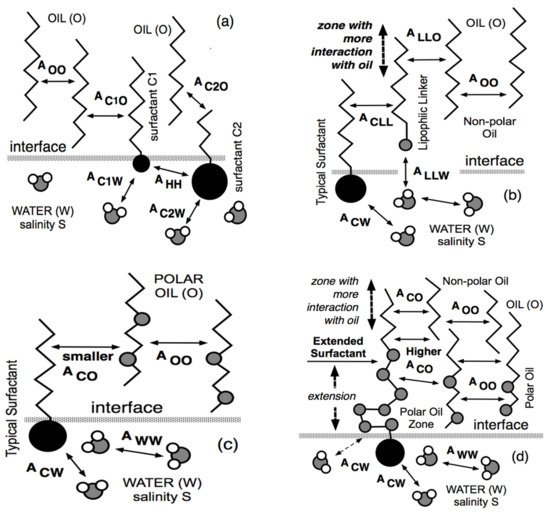

Extended surfactants are molecules including an intramolecular extension that allow attaining high performance without the need for cosurfactant or linker alcohol. The polypropylene oxide chain intramolecular extension generates a polarity transition inside the molecule that produces more interactions with the oil and aqueous phases. The idea was developed in the 1990s, basically to fasten together the rather hydrophilic surfactant and the lipophilic linker, producing the same effect as the mixture without losing a part of the lipophilic linker going away from the interface. Since the lipophilic linker was an amphiphile with a small hydrophilic part located close to the interface, the single structure was developed to imitate the mixture situation. It contains a polar head located in water, then an intermediate slightly polar zone in the oil phase close to the interface, and finally, the surfactant classical hydrocarbon tail.

- formulation

- normalized hydrophilic–lipophilic deviation HLDN

- extended surfactant

- solubilization

- enhanced oil recovery

- interfacial tension

This is an entry from Forgiarini, A.M.; Marquez, R.; Salager, J.-L. Molecules 2021, 26, 3771. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules26123771

Laboratorio Firp, Universidad de Los Andes, Merida, Venezuela

1. Introduction

Table 1.

Molecular structure and classification of sulfate head extended surfactants according to its normalized characteristic parameter (SCPN)

[2]

Extended Surfactant 1

σ

k

SCPN= σ/k*

Author and year

Ref.

S/12/6/2/SO4

-1.43

0.075

-19.1

Miñana-Perez, 1995

[13]

S/12/10/2/SO4

-0.3

0.11

-2.7

Miñana-Perez, 1995

[13]

S/12/14/2/SO4

1.21

0.16

7.6

Miñana-Perez, 1995

[13]

A/14-15/8/0/SO4

0.16

0.13

1.2

Witthayapanyanon, 2006

[30]

A/10/18/2/SO4

0.57

0.053

10.8

Do, 2009

[39]

A/14-15/4/0/SO4

-0.18

0.11

-1.6

Velásquez, 2010

[24]

A/16-17/4/0/SO4

-0.29

0.11

-2.6

Velásquez, 2010

[24]

A/12-13/8/0/SO4

-0.52

0.08

-6.5

Velásquez, 2010

[24]

A/12-13/4/0/SO4

-0.98

0.11

-8.9

Velásquez, 2010

[24]

Chen/8/9/3/SO4

-0.39

0.17

-2.3

Chen, 2019

[40]

A/12-13/4/0/SO4

-1.55

0.049

-31.6

Wang, 2019

[41]

He/13/2/0/SO4

-1.8

0.056

-32.1

He, 2019

[42]

A/10/4/0/SO4

-2.24

0.053

-42.3

Phaodee, 2020

[43]

| Extended Surfactant 1 | σ | k | SCPN = σ/k * | Author and Year | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S/12/6/2/SO4 | −1.43 | 0.075 | −19.1 | Miñana-Perez, 1995 | [13] |

| S/12/10/2/SO4 | −0.3 | 0.11 | −2.7 | Miñana-Perez, 1995 | [13] |

| S/12/14/2/SO4 | 1.21 | 0.16 | 7.6 | Miñana-Perez, 1995 | [13] |

| A/14−15/8/0/SO4 | 0.16 | 0.13 | 1.2 | Witthayapanyanon, 2006 | [30] |

| A/10/18/2/SO4 | 0.57 | 0.053 | 10.8 | Do, 2009 | [39] |

| A/14−15/4/0/SO4 | −0.18 | 0.11 | −1.6 | Velásquez, 2010 | [24] |

| A/16−17/4/0/SO4 | −0.29 | 0.11 | −2.6 | Velásquez, 2010 | [24] |

| A/12−13/8/0/SO4 | −0.52 | 0.08 | −6.5 | Velásquez, 2010 | [24] |

| A/12−13/4/0/SO4 | −0.98 | 0.11 | −8.9 | Velásquez, 2010 | [24] |

| Chen/8/9/3/SO4 | −0.39 | 0.17 | −2.3 | Chen, 2019 | [79] |

| A/12−13/4/0/SO4 | −1.55 | 0.049 | −31.6 | Wang, 2019 | [41] |

| He/13/2/0/SO4 | −1.8 | 0.056 | −32.1 | He, 2019 | [42] |

| A/10/4/0/SO4 | −2.24 | 0.053 | −42.3 | Phaodee, 2020 | [29] |

1Nomenclature: A: Alfoterra, S: Seppic, Chen and He are first authors of the papers where these surfactants were synthetized. A/10/18/2/S stands for Alfoterra/C10/PO18/O2/SO4. This is the same nomenclature as [2].

*SCPN is the surfactant classification parameter. Higher SCPN indicates a more important lipophilic part of the molecule (hydrocarbon tail and PO extension), a lower SCPN (more negative) indicates a more important hydrophilic head contribution.

2. Historical Introduction on Formulation Concepts

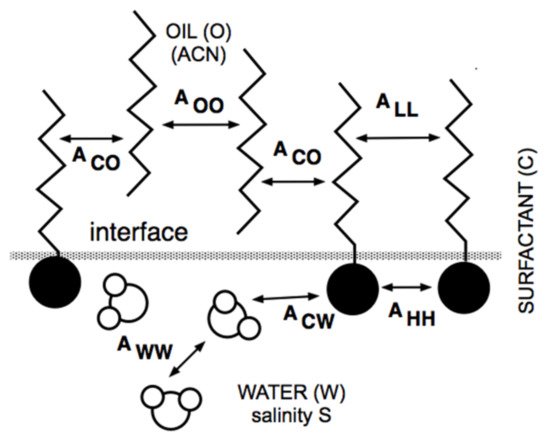

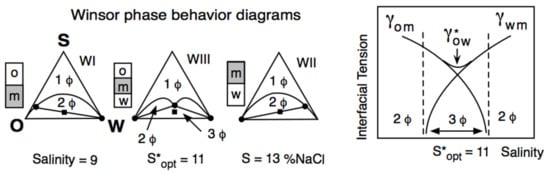

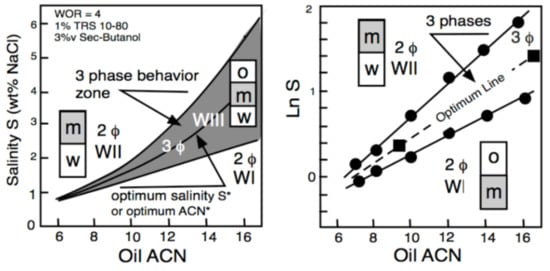

It can be said that a century ago, the so-called Bancroft’s rule and its related research and development discussions [37][38][39] were the first attempt to attain a generalized practical approach for surfactant–oil–water (SOW) systems. However, it was only in the late 1950s that two researchers from industry tried to improve the practical aspects related to SOW systems. Griffin [40] introduced the so-called hydrophilic-lipophilic balance parameter, called HLB. Sometime later [41], he proposed several numerical expressions to estimate the HLB number as a function of the chemical structure of nonionic surfactants, e.g., 20% of the polyoxyethylene weight for an ethoxylated alcohol. HLB was related to the surfactant effect and was thus the first numerical scale that could help compare cases and averaging effects. Even though it did not take into account the effect of other variables, it was the unique numerical criterion for 25 years because it was an extremely simple concept. Thus, it is still currently used as approximate information for people in the industry who do not require high accuracy in formulation work [42]. At the same time, but in a completely different research area, Winsor [43] proposed a complex model based on the ratio R of interactions between the surfactant adsorbed at the interface and the neighboring oil and water molecules on both sides of it, indicated explicitly as ACO and ACW in Figure 1.

The Unidimensional Scan of a Formulation Variable

The Unidimensional Scan of a Formulation Variable

3. Multivariable Scans and Generalized HLD Expression for Optimum Formulation

| HLD Equation–Surfactant Type |

|---|

| ΔHLD | 1 | = ΔLnS − 0.16 ΔACN = 0 for alkylbenzene sulfonates ΔHLD | 2 | = ΔLnS − 0.19 ΔACN = 0 for alkyltrimethyl ammonium chlorides ΔHLD | 3 | = ΔLnS − 0.07 ΔACN = 0 for alkyl hexapropyleneoxide diethylenoxide sulfates ΔHLD | 4 | = 0.33 ΔSAT − ΔEON = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 and T~25 °C ΔHLD | 5 | = 0.13 ΔS − ΔEON = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 and T~25 °C ΔHLD | 6 | = 2.25 ΔSAT − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 ΔHLD | 7 | = − 0.24 ΔACN − ΔEON = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 ΔHLD | 8 | = − ΔT − 20 ΔACN = 0 for | n | -alkyl sulfates ΔHLD | 9 | = − ΔT − 14.3 ΔACN = 0 for alkylbenzene sulfonates ΔHLD | 10 | = ΔT − 4 ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~5–6 & T~20–30 °C) ΔHLD | 11 | = ΔT − 1.4 ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~8–9 & T~70 °C) ΔHLD | 12 | = ΔT − 0.90 ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~10–11 & T~80–90 °C) ΔHLD | 13 | = − ΔGN − 0.12 ΔACN = 0 for polyglyceryl monolaurate (GN~5–6) ΔHLD | 14 | = ΔLnS − 0.14 ΔPON = 0 for alkyl polypropyleneoxide diethylenoxide sulfates |

where S is the salinity in wt% NaCl, EON is the exact or average number of ethylene oxide groups, SAT is the surfactant n-alkyl tail length in carbon atom number, T is the temperature in °C, and GN is the number of glyceryl group in polyglyceryl monolaurate oligomers.

3.1. The Normalized Hydrophilic Lipophilic Deviation (HLD

N

) Equation

| HLD | N | Equation−Surfactant Type |

|---|

| ΔHLD | N1 | = 6.25 ΔLnS − ΔACN = 0 for alkylbenzene sulfonates ΔHLD | N2 | = 5.26 ΔLnS − ΔACN = 0 for alkyltrimethyl ammonium chlorides ΔHLD | N3 | = 14.3 ΔLnS − ΔACN = 0 for alkyl hexapropyleneoxide diethylenoxide sulf. ΔHLD | N4 | = 1.4 ΔSAT − 4.2 ΔEON = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol (EON~5 & T~25 °C) ΔHLD | N5 | = 0.55 ΔS − 4.2 ΔEON = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol (EON~5 & T~25 °C) ΔHLD | N6 | = 2.25 ΔSAT − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 ΔHLD | N7 | = − 4.2 ΔEON − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated | n | -alcohol with EON~5 ΔHLD | N8 | = − 0.05 ΔT − ΔACN = 0 for | n | -alkyl sulfates ΔHLD | N9 | = − 0.07 ΔT − ΔACN = 0 for alkylbenzene sulfonates ΔHLD | N10 | = 0.25 ΔT − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~5–6 & T~20–30 °C) ΔHLD | N11 | = 0.70 ΔT − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~8–9 & T~70 °C) ΔHLD | N12 | = 1.1 ΔT − ΔACN = 0 for ethoxylated nonionic (EON~11 & T~80–90 °C) ΔHLD | N13 | = − 8.3 ΔGN − ΔACN = 0 for polyglyceryl monolaurate (GN~5–6) ΔHLD | N14 | = 1.2 ΔPON − ΔACN = 0 for alkyl polypropyleneoxide PON sulfates |

3.2. The Normalized Surfactant Characteristic Parameter (SCP

3.2. The Normalized Surfactant Characteristic Parameter (SCP

N

)

4. Lipophilic and Hydrophilic Linkers, and Extended Surfactants

4.1. The Lipophilic Linker

4.1. The Lipophilic Linker

4.2. The Hydrophilic Linker

4.2. The Hydrophilic Linker

4.3. The Extended Surfactant with an Intramolecular PO Extension

4.3. The Extended Surfactant with an Intramolecular PO Extension

4.4. The Increased Performance of Extended Surfactant Systems with Polar Oils and Crude Oils

4.4. The Increased Performance of Extended Surfactant Systems with Polar Oils and Crude Oils

References

- Salager, J.-L.; Antón, R.E.; Sabatini, D.A.; Harwell, J.H.; Acosta, E.; Tolosa, L.I. Enhancing solubilization in microemulsions-State of the art and current trends. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2005, 8, 3.

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.; Marquez, R. Extended Surfactants Including an Alkoxylated Central Part Intermediate Producing a Gradual Polarity Transition—A Review of the Properties Used in Applications Such as Enhanced Oil Recovery and Polar Oil Solubilization in Microemulsions. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 22.

- Bourrel, M.; Lipow, A.M.; Wade, W.H.; Schechter, R.S.; Salager, J.-L. Properties Of Amphiphile/Oil/Water Systems At An Optimum Formulation For Phase Behavior. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Fall Technical Conference and Exhibition, Houston, TX, USA, 1–3 October 1978.

- Doe, P.; El-Emary, M.; Wade, W.H.; Schechter, R.S. Surfactants for producing low interfacial tensions I: Linear alkyl benzene sulfonates. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1977, 54, 570–577.

- Salager, J.-L. Physico-Chemical Properties of Surfactant-Water-Oil Mixtures: Phase Behavior, Micro-Emulsion Formation and Interfacial Tension. Ph.D. Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, USA, 1977.

- Carmona, I.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H.; Weerasooriya, U. Ethoxylated Oleyl Sulfonates As Model Compounds for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1985, 25, 351–357.

- Abe, M.; Schechter, D.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H.; Weerasooriya, U.; Yiv, S. Microemulsion formation with branched tail polyoxyethylene sulfonate surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1986, 114, 342–356.

- Maerker, J.M.; Gale, W.W. Surfactant flood process design for Loudon. SPE Reserv. Eng. 1992, 7, 36–44.

- Salager, J.-L. A normalized Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Deviation expression HLDN is necessary to avoid confusions close to the optimum formulation of Surfactant-Oil-Water systems. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2021.

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Bullón, J.; Marquez, R.; Alvarado, J.G. A Review on the Surfactant Characteristic Parameter used in Enhanced Oil Recovery, Crude Oil Dehydration and Other Formulation Applications. FIRP Booklet E729B. 2014. Available online: (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Salager, J.-L.; Antón, R.E.; Bullón, J.; Forgiarini, A.; Marquez, R. How to Use the Normalized Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Deviation (HLDN) Concept for the Formulation of Equilibrated and Emulsified Surfactant-Oil-Water Systems for Cosmetics and Pharmaceutical Products. Cosmetics 2020, 7, 57.

- Baran, J.R.; Pope, G.A.; Wade, W.H.; Weerasooriya, V. Phase Behavior of Water/Perchloroethylene/Anionic Surfactant Systems. Langmuir 1994, 10, 1146–1150.

- Miñana-Perez, M.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Salager, J.-L. Solubilization of polar oils with extended surfactants. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1995, 100, 217–224.

- Aoudia, M.; Wade, W.H.; Weerasooriya, V. Optimum microemulsions formulated with propoxylated Guerbet alcohol and propoxylated tridecyl alcohol sodium sulfates. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1995, 16, 115–135.

- Minana-Perez, M.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Salager, J.L. Systems containing mixtures of extended surfactants and conventional nonionics. Phase behavior and solubilization in microemulsion. In Proceedings of the 4th World Surfactants Congress, Barcelona, Spain, 3–7 June 1996; Volume 2, pp. 226–234.

- Pérez, M.M.; Salager, J.-L.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J. Solubilization of polar oils in microemulsion systems. Trends Colloid Interface Sci. IX 1995, 177–179.

- Scorzza, C.; Godé, P.; Goethals, G.; Martin, P.; Miñana-Pérez, M.; Salager, J.L.; Usubillaga, A.; Villa, P. Another new family of “extended” glucidoamphiphiles. Synthesis and surfactant properties for different sugar head groups and spacer arm lengths. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2002, 5, 337–343.

- Scorzza, C.; Godé, P.; Martin, P.; Miñana-Pérez, M.; Salager, J.L.; Villa, P.; Goethals, G. Synthesis and surfactant properties of a new “extended” glucidoamphiphile made from D-glucose. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2002, 5, 331–335.

- Goethals, G.; Fernández, A.; Martin, P.; Miñana-Pérez, M.; Scorzza, C.; Villa, P.; Godé, P. Spacer arm influence on glucidoamphiphile compound properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2001, 45, 147–154.

- Salager, J.; Scorzza, C.; Forgiarini, A.; Arandia, M.A.; Pietrangeli, G.; Manchego, L.; Vejar, F. Amphiphilic Mixtures versus Surfactant Structures with Smooth Polarity Transition across Interface to Improve Solubilization Performance. In Proceedings of the CESIO 2008—7th World Surfactant Congress Paris Session: Design and Analisis—Paper Number O-A17, Paris, France, 22–25 June 2008; pp. 1–9.

- Fernández, A.; Scorzza, C.; Usubillaga, A.; Salager, J.-L. Synthesis of new extended surfactants containing a carboxylate or sulfate polar group. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2005, 8, 187–191.

- Fernández, A.; Scorzza, C.; Usubillaga, A.; Salager, J. Synthesis of new extended surfactants containing a xylitol polar group. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2005, 8, 193–198.

- Illous, E.; Ontiveros, J.F.; Lemahieu, G.; Lebeuf, R.; Aubry, J.M. Amphiphilicity and salt-tolerance of ethoxylated and propoxylated anionic surfactants. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 601, 124786.

- Velásquez, J.; Scorzza, C.; Vejar, F.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Antón, R.E.; Salager, J.L. Effect of temperature and other variables on the optimum formulation of anionic extended surfactant-alkane-brine systems. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2010, 13, 69–73.

- Arandia, M.A.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Salager, J.-L. Resolving an enhanced oil recovery challenge: Optimum formulation of a surfactant-oil-water system made insensitive to dilution. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2010, 13, 119–126.

- Forgiarini, A.M.; Scorzza, C.; Velásquez, J.; Vejar, F.; Zambrano, E.; Salager, J. Influence of the mixed propoxy/ethoxy spacer arrangement order and of the ionic head group nature on the adsorption and aggregation of extended surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2010, 13, 451–458.

- Solairaj, S.; Britton, C.; Lu, J.; Kim, D.H.; Weerasooriya, U.; Pope, G.A. New correlation to predict the optimum surfactant structure for EOR. In Proceedings of the SPE—DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 14–18 April 2012; Volume 2, pp. 1390–1399.

- Yang, H.; Britton, C.; Liyanage, P.J.; Solairaj, S.; Kim, D.H.; Nguyen, Q.; Weerasooriya, U.; Pope, G.A. Low-cost, high-performance chemicals for enhanced oil recovery. Proceedings SPE—DOE Improved Oil Recovery Symposium, Tulsa, OK, USA, 24–28 April 2010; Volume 2, pp. 1474–1497.

- Phaodee, P.; Sabatini, D.A. Effect of Surfactant Systems, Alcohol Types, and Salinity on Cold-Water Detergency of Triacylglycerol Semisolid Soil. Part II. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2020, 23, 423–432.

- Witthayapanyanon, A.; Acosta, E.; Harwell, J.H.; Sabatini, D.A. Formulation of ultralow interfacial tension systems using extended surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2006, 9, 331–339.

- Salager, J.L.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Antón, R.E.; Quintero, L. Available know-how in transforming an emulsified drilling fluid to be removed from an unwanted location into a low-viscosity single-phase system. Energy Fuels 2012, 26, 4078–4085.

- Quintero, L.; Clark, D.E.; Salager, J.; Forgiarini, A. Mesophase Fluids with Extended Chain Surfactants for Downhole Treatments. US Patent Office US8235120B2, 7 August 2012.

- Quintero, L.; Clark, D.E.; Cardenas, A.E.; Salager, J.; Forgiarini, A.; Bahsas, A.H. Dendritic Surfactants and Extended Surfactants for Drilling Fluid Formulations. US Patent Office US20120241220A1, 27 September 2012.

- Delgado-Linares, J.G.; Pereira, J.C.; Rondón, M.; Bullón, J.; Salager, J.L. Breaking of Water-in-Crude Oil Emulsions. 6. Estimating the Demulsifier Performance at Optimum Formulation from Both the Required Dose and the Attained Instability. Energy Fuels 2016, 30, 5483–5491.

- Pereira, J.C.; Delgado-Linares, J.; Scorzza, C.; Rondón, M.; Rodríguez, S.; Salager, J.-L. Breaking of Water-in-Crude Oil Emulsions. 4. Estimation of the Demulsifier Surfactant Performance To Destabilize the Asphaltenes Effect. Energy Fuels 2011, 25, 1045.

- Marquez, R.; Forgiarini, A.; Langevin, D.; Salager, J.-L. Breaking of Water-In-Crude Oil Emulsions. Part 9. New Interfacial Rheology Characteristics Measured Using a Spinning Drop Rheometer at Optimum Formulation. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 8151–8164.

- Roon, L.; Oesper, R.E. A Contribution to the Theory of Emulsification Based on Pharmaceutical Practice. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1917, 9, 156–161.

- Crockett, W.G.; Oesper, R.E. A Contribution to the Theory of Emulsification Based on Pharmaceutical Practice-II. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1917, 9, 967–969.

- Harkins, W.D.; McLaughlin, H.M. The structure of films of water on salt solutions I. Surface tension and adsorption for aqueous solutions of sodium chloride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1925, 47, 2083–2089.

- Griffin, W. Classification of surface-active agents by “HLB”. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1949, 1, 311–326.

- Griffin, W. Calculation of HLB Values of Non-ionic Surfactants. J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 1954, 5, 249.

- Becher, P. Emulsions: Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 0-8412-3496-5.

- Winsor, P. Hydrotropy, solubilisation and related emulsification processes. Trans. Faraday Soc. 1948, 44, 376–398.

- Winsor, P. Solvent Properties of Amphiphilic Compounds; Butterworths Scientific Publications: Oxford, UK, 1954.

- Winsor, P. Binary and multicomponent solutions of amphiphilic compounds. Solubilization and the formation, structure, and theoretical significance of liquid crystalline solutions. Chem. Rev. 1968, 68, 1–40.

- Bourrel, M.; Verzaro, F.; Chambu, C. Effect of Oil Type on Solubilization by Amphiphiles. SPE Reserv. Eng. 1987, 2, 41–53.

- Bourrel, M.; Schechter, R.S. Microemulsions and Related Systems: Formulation, Solvency, and Physical Properties; Editions Technip: Paris, France, 2010; ISBN 2710809567.

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Bullón, J. How to attain ultralow interfacial tension and three-phase behavior with surfactant formulation for enhanced oil recovery: A review. Part 1. Optimum formulation for simple surfactant-oil-water ternary systems. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2013, 16, 449–472.

- Ghosh, S.; Johns, R.T. Dimensionless Equation of State to Predict Microemulsion Phase Behavior. Langmuir 2016, 32, 8969–8979.

- Fotland, P.; Skange, A. Ultralow Interfacial Tension as a Function of Pressure. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1986, 7, 563.

- Austad, T.; Strand, S. Chemical flooding of oil reservoirs 4. Effects of temperature and pressure on the middle phase solubilization parameters close to optimum flood conditions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1996, 108, 243–252.

- Salager, J.-L.; Morgan, J.C.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H.; Vasquez, E. Optimum formulation of surfactant/water/oil systems for minimum interfacial tension or phase behavior. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1979, 19, 107–115.

- Salager, J.L. Quantifying the concept of physico-chemical formulation in surfactant-oil-water systems—state of the art. Trends Colloid Interface Sci. X 1996, 137–142.

- Antón, R.E.; Garcés, N.; Yajure, A. A correlation for three-phase behavior of cationic surfactant-oil-water systems. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1997, 18, 539–555.

- Hammond, C.E.; Acosta, E.J. On the characteristic curvature of alkyl-polypropylene oxide sulfate extended surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2012, 15, 157–165.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Morgan, C.; Poindexter, L.; Fernandez, J. Application of the Hydrophilic–Lipophilic Deviation Concept to Surfactant Characterization and Surfactant Selection for Enhanced Oil Recovery. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2019, 22, 983–999.

- Barakat, Y.; Fortney, L.N.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H.; Yiv, S.H.; Graciaa, A. Criteria for structuring surfactants to maximize solubilization of oil and water: II. Alkyl benzene sodium sulfonates. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1983, 92, 561–574.

- Bourrel, M.; Salager, J.-L.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H. A correlation for phase behavior of nonionic surfactants. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1980, 75, 451–461.

- Antón, R.E.; Salager, J.-L. Effect of the Electrolyte Anion on the Salinity Contribution to Optimum Formulation of Anionic Surfactant Microemulsions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1990, 140, 75.

- Aubry, J.M.; Ontiveros, J.F.; Salager, J.-L.; Nardello-Rataj, V. Use of the normalized hydrophilic-lipophilic-deviation (HLDN) equation for determining the equivalent alkane carbon number (EACN) of oils and the preferred alkane carbon number (PACN) of nonionic surfactants by the fish-tail method (FTM). Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2020, 276.

- Salager, J.-L.; Bourrel, M.; Schechter, R.S.; Wade, W.H. Mixing Rules for Optimum Phase Behavior Formulation of Surfactant-Oil-Water Systems. Soc. Pet. Eng. J. 1979, 19, 271.

- Acosta, E.; Yuan, J.S.; Bhakta, A.S. The characteristic curvature of ionic surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2008, 11, 145.

- Salager, J.-L.; Marquez, N.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J. Partitioning of ethoxylated octylphenol surfactants in microemulsion-oil-water systems: Influence of temperature and relation between partitioning coefficient and physicochemical formulation. Langmuir 2000, 16, 5534–5539.

- Marquez, N.; Anton, R.E.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Salager, J.L. Partitioning of ethoxylated alkylphenol surfactants in microemulsion-oil-water systems. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1995, 100, 225–231.

- Márquez, N.; Anton, R.E.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Salager, J.-L. Partitioning of ethoxylated alkylphenol surfactants in microemulsion- oil-water systems. Part II: Influence of hydrophobe branching. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 1998, 131, 45–49.

- Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Cucuphat, C.; Bourrel, M.; Salager, J.L. Interfacial Segregation of an Ethyl Oleate/Hexadecane Oil Mixture in Microemulsion Systems. Langmuir 1993, 9, 1473–1478.

- Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Cucuphat, C.; Bourrel, M.; Salager, J.L. Improving solubilization in microemulsions with additives. 1. The lipophilic linker role. Langmuir 1993, 9, 669–672.

- Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Cucuphat, C.; Bourrel, M.; Salager, J.L. Improving Solubilization in Microemulsions with Additives. 2. Long Chain Alcohols as Lipophilic Linkers. Langmuir 1993, 9, 3371–3374.

- Salager, J.L.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J. Improving solubilization in microemulsions with additives. Part III: Lipophilic linker optimization. J. Surfactants Deterg. 1998, 1, 403–406.

- Acosta, E.; Do Mai, P.; Harwell, J.H.; Sabatini, D.A. Linker-Modified Microemulsions for a Variety of Oils and Surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2003, 6, 353–363.

- Quintero, L.; Pietrangeli, G.; Hughes, B.; Salager, J.L.; Forgiarini, A. Optimization of microemulsion formulations with linker molecules. In Proceedings of the SPE–European Formation Damage Conference, EFDC, Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 5–7 June 2013; Volume 2, pp. 1275–1287.

- Acosta, E.; Uchiyama, H.; Sabatini, D.A.; Harwell, J.H. The role of hydrophilic linkers. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2002, 5, 151–157.

- Frank, C.; Frielinghaus, H.; Allgaier, J.; Richter, D. Hydrophilic alcohol ethoxylates as efficiency boosters for Microemulsions. Langmuir 2008, 24, 6036–6043.

- Miñana-Pérez, M. Contribution à la Microémulsification d’huiles Polaires de Synthèse ou Naturelles. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Los Andes—Universite de Pau, Santiago, Chile, 1993.

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.M. Extended surfactants A fine tuned structure to improve interfacial performance. In Proceedings of the 101st AOCS Annual Meeting, Phoenix, AZ, USA, 16–19 May 2010.

- Salager, J.L.; Scorzza, C.; Fernandez, A.; Antón, R.E.; Miñana-Pérez, M.; Usubillaga, A.; Villa, P. Enhancing Solubilization in Microemulsions: From Classic To Novel “Extended” Surfactant Structures. In Proceedings of the Surfactants in Solution, Barcelona, Spain, 9–14 June 2002.

- Salager, J.; Forgiarini, A.; Marquez, L. Understanding of Extended Surfactants Intramolecular Structure to enhance solubilization for a variety of applications. In Proceedings of the 8th World Surfactant Congress CESIO, Vienna, Austria, 6–8 June 2011.

- Chen, J.; Hu, X.Y.; Fang, Y.; Liu, H.H.; Xia, Y.M. Comparative Study of Conventional/Ethoxylated/Extended n-Alkylsulfate Surfactants. Langmuir 2019, 35, 3116–3125.

- Chen, J.; Hu, X.Y.; Fang, Y.; Jin, G.Y.; Xia, Y.M. What dominates the interfacial properties of extended surfactants: Amphipathicity or surfactant shape? J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 547, 190–198.

- Lu, J.; Britton, C.; Solairaj, S.; Liyanage, P.J.; Kim, D.H.; Adkins, S.; Arachchilage, G.W.P.; Weerasooriya, U.; Pope, G.A. Novel large-hydrophobe alkoxy carboxylate surfactants for enhanced oil recovery. SPE J. 2014, 19, 1024–1034.

- Han, X.; Lu, M.; Fan, Y.; Li, Y.; Holmberg, K. Recent Developments on Surfactants for Enhanced Oil Recovery. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2021, 58, 164–176.

- Ghosh, S.; Johns, R.T. An Equation-of-State Model To Predict Surfactant/Oil/Brine-Phase Behavior. SPE J. 2016, 21, 1106.

- Chung, J.; Holtsclaw, J.; Henderson, T.C.; Everett, T.A.; Schultheiss, N.C.; Boudouris, B.W.; Franses, E.I. Relationship of Various Interfacial Tensions of Surfactants/Brine/Oil Formulations to Oil Recovery Efficiency. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 7768–7777.

- Antón, R.E.; Graciaa, A.; Lachaise, J.; Salager, J.L. Surfactant-Oil-Water Systems Near the Affinity Inversion, Part VIII: Optimum Formulation and Phase Behavior of Mixed Anionic-Nonionic Systems Versus Temperature. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 1992, 13, 565–579.

- Acosta, E.; Bhakta, A.S. The HLD-NAC model for mixtures of ionic and nonionic surfactants. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2009, 12, 7–19.

- Gagnon, Y.; Mhemdi, H.; Delbecq, F.; Van Hecke, E. Extended surfactants and their tailored applications for vegetable oils extraction: An overview. OCL Oilseeds Fats Crop. Lipids 2021, 28.

- Salager, J.-L.; Forgiarini, A.M.; Rondón, M.J. How to Attain an Ultralow Interfacial Tension and a Three-Phase Behavior with a Surfactant Formulation for Enhanced Oil Recovery: A Review—Part 3. Practical Procedures to Optimize the Laboratory Research according to the Current State of the Art in Surf. J. Surfactants Deterg. 2017, 20, 3.