Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among men around the world. Radiotherapy is a standard of care treatment option for men with localized prostate cancer. Over the years, radiation delivery modalities have contributed to increased precision of treatment, employing radiobiological insights to shorten the overall treatment time, improving the control of the disease without increasing toxicities.

- extreme hypofractionation

- hypofractionation

- prostate cancer

- stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

1. Introduction

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT) is considered one of the standard treatments for organ-confined prostate cancer (PCa), with cure rates similar to those of radical prostatectomy. Hypofractionation uses a higher dose-per-fraction of radiation, which reduces the number of fractions and the total duration of treatment, allowing greater comfort for the patient and lower costs, in addition to providing a therapeutic advantage in terms of tumor control and toxicity, as the α/β of PCa is lower than that of adjacent healthy tissues [1]. In 2018, a group of experts from the American Societies of Radiation Oncology, Medical Oncology, and Urology (ASTRO/ASCO/AUA) concluded that there is sufficiently robust evidence to justify using moderate hypofractionation in PCa as common clinical practice [2], and a recent Cochrane review indicated that moderate PCa hypofractionation (with fractions up to 3.4 Gy) provides oncological outcomes in terms of overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), and metastasis-free survival (MFS) similar to conventional fractionation, without a significant increase in acute or late toxicity [3].

In addition, technical advances in the field of radiotherapy in recent years, such as intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT), image-guided radiotherapy (IGRT), and stereotactic radiotherapy (SBRT), have enabled the progressive implementation of extreme hypofractionation (defined by fractions of at least six Gy) in various scenarios of localized PCa treatment. The use of SBRT in PCa has provided sufficient evidence in terms of tumor control results, quality of life reported by the patient, and low toxicity [4][5][6][4,5,6] to back its implementation in daily clinical practice. Moreover, the PCa working group of the German Society of Oncology (DEGRO) endorses the use of SBRT in the treatment of localized low- and intermediate-risk PCa, recommending its use in clinical trials in patients with the localized high-risk disease [7].

The recent publication of two randomized trials comparing the use of extreme hypofractionation versus conventional fractionation (HYPO-RT-PC [5], PACE-B trial [6]) has been crucial in supporting its use, although only the Scandinavian study (HYPO-RT-PC) reported results of long-term tumor and toxicity control. In 2020, a randomized systematic review and meta-analysis of phase III trials were published comparing SBRT with normofractionated and hypofractioned regimens. It concluded that the ultra-hypofractionated regimens obtained similar 5-year disease-free survival results, with late gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicity of <15% and <21%, respectively, when compared to hypofractionated regimens and conventional radiotherapy [8].

At a time when there is growing interest in adopting extreme fractionation schedules in treating PCa in our usual practice, this review aims to capture the current evidence and recommendations for using it in different scenarios of PCa treatment.

2. SBRT in Low- and Intermediate-Risk Prostate Cancer

There are multiple published prospective trials in which thousands of patients with extreme hypofractionation have been treated, with different doses, fractions, and techniques. The most relevant have been analyzed in four reviews or meta-analysis studies.

In 2019, Roy and Morgan published a review of the hypofractionated and ultra-hypofractionated studies in localized prostate cancer. They concluded that SBRT is an option in treating patients with low and intermediate-risk, even though the evidence remains less solid than that supporting the use of moderate hypofractionation in these groups of risk [9][27].

A review of studies conducted between 2001 and 2018 evaluating genitourinary, gastrointestinal, and sexual effects in patients treated with SBRT has recently been published [10][28], describing a relationship between dose received and genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity. However, there are few studies that examine the possible relationship between erectile dysfunction and dose to organs at risk (OAR) [11][29].

Pending the results of biochemical control and late toxicity of PACE-B, Widmark et al. establish the bases of what could be the standard of care in patients with localized PCa, considering certain features.

3. SBRT in High-Risk Prostate Cancer

The administration of combined ERT treatments, which additionally applied a boost with SBRT, has been analyzed in a lower percentage of patients. The follow-ups in published studies have been short [12][13][36,37].

Despite the high level of available evidence of increased overall survival with ADT addition to normal and hypofractionated radiotherapy in high-risk patients, its appearance in SBRT studies with this subgroup of patients is very heterogeneous, with its use in some series being omitted [14][15][32,33], and widespread omission of ADT in published studies of intermediate-risk patients [16][17][11,12].

At this time, we cannot establish the true role of ADT or its optimal duration in high-risk patients treated with SBRT, given the lack of sufficient levels of evidence for this subgroup of patients. Regarding the optimal sequencing to administer treatment with ADT in combination with SBRT in localized prostate cancer, there are no data in published studies in which ADT is used that indicate the optimal period to start ADT treatment [18][19][34,44], using as reference the timing established in studies employing normo- or moderate hypofractionated regimens [20][21][22][41,42,43].

Prophylactic nodal irradiation with normofractionated radiotherapy in patients with high-risk PCa has shown an increase in bRFS and DFS rates without showing benefits in OS [23][45]. Three studies have analyzed prophylactic lymph node irradiation with SBRT to date, one of them prematurely halted because of high rates of genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity [24][46].

4. SBRT on Prostate Bed

Radical prostatectomy remains a standard treatment for prostate adenocarcinoma. However, up to 33% of patients will experience a biochemical relapse at follow-up [25][26][49,50].

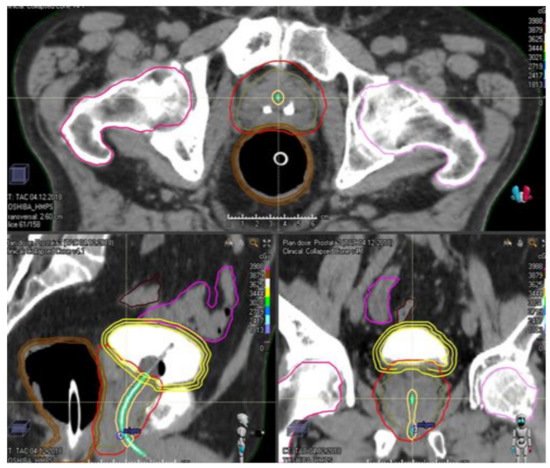

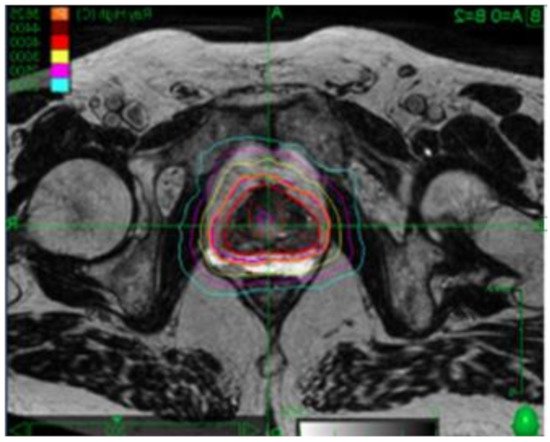

Postprostatectomy radiotherapy includes both early adjuvant radiotherapy after surgery (ART) and salvage radiotherapy in patients with a recurrence of abnormal PSA levels after surgery (biochemical relapse). To demonstrate the viability and safety of the use of SBRT in this clinical scenario, Repka et al. [27][51] conducted a theoretical feasibility study of SBRT after prostatectomy based on the NTCP (Normal Tissue Complication Probability) model, using patients who had previously been treated by conventional EBRT for biochemical recurrence after prostatectomy. Using the presimulation CT, RTOG recommendations were applied to define postprostatectomy volumes, and a dose of 30 Gy was prescribed to the PTV in five fractions, corresponding to an equivalent dose in 2 Gy fractions (EQD2) of 64.3 Gy, assuming an α/β value of 1.5. The NTCP model was applied to estimate the risk of late rectal and/or bladder toxicity. According to the NTCP model, the mean of grade ≥ 2 late rectal toxicity was estimated at 0.28% (±0.03%) and of late grade 2 toxicity on the bladder neck at 0.00013% (±0.000084%), while the calculated average for the exacerbation of late urinary symptoms was 4.81% (±0.52%). The conclusion by the authors, considering the limitations of the NTCP model, is that using SBRT after surgery seems feasible and may offer a safe, convenient treatment option for patients in both the adjuvant and salvage after biochemical failure. Table 12 shows a comparative analysis of equivalent doses in terms of EQD2 and biological effective dose (BED) with three different treatment schedules (normofractionation, moderate hypofractionation, and ultra-hypofractionation or SBRT).

| Radiotherapy Schedules | Total Dose (Gy) | Dose/Fraction (Gy) | Number of Fractions | EQD2 (Gy1,5) | BED (Gy1,5) | EQD2 (Gy3) | BED (Gy3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional fractionation | 70 | 2 | 35 | 70 | 163.3 | 70 | 116.7 |

| Moderate hypofractionation | 62.5 | 2.5 | 25 | 71.4 | 166.7 | 68.8 | 114.6 |

| Ultra-hypofractionation–SBRT | 37.25 | 7.25 | 5 | 90.6 | 211.5 | 74.3 | 123.9 |

In recent years, various studies have explored the possibility of administering SBRT for treating the prostate bed ( Table 23 ). Sampath et al. performed a postprostatectomy SBRT dose-escalation study up to 45 Gy in five fractions. Although 45 Gy in five fractions was safe for prostate bed SBRT, it did not improve clinical outcomes, so the authors recommend a total dose of 40 Gy in five fractions as a prescription dose [28][29][52,53]. Ballas et al. performed a phase I trial in 24 patients with three dose levels: Fifteen fractions of 3.6 Gy, 10 × 4.7 Gy, and 5 × 7.1 Gy. With a median follow-up of 1.2 years, dose-escalation showed promising results, with no patients experiencing relevant severe toxicities (grade ≥ 3) [30][54]. A recent phase II multicenter trial in which 30–34 Gy was administered in five fractions to the prostate bed reported its dosimetric results after applying a specific bladder and rectum filling protocol. In this study, cone-beam CT intrafraction showed that CTV volume remained stable, with minimal volumetric and dosimetric changes, although patients with 95% CTV < 93% had a higher risk of CTV intrafraction volume changes [31][55]. In view of the recent data from the SAKK 09/10 study [32][56], the dose going forward in the next few years should probably be 30 Gy in five fractions as suggested by Repka et al. [27][51], pending validation in future clinical trials.

| Extreme Hypofractionation Studies after Prostatectomy | Sampath 2020 | Ballas 2019 | Detti 2015 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N patients | 3 | 8 | 15 | 12 | 16 (50% after surgery and radiation therapy; 50% after only surgery) | |

| SBRT dose | 7 Gy × 5, alternate days | 8 Gy × 5, alternate days | 9 Gy × 5, alternate days | 7.1 Gy × 5, consecutive days | 6 Gy × 5 after previous surgery and radiation therapy on alternate days 7 Gy × 5 after only surgery on alternate days |

|

| ART/SRT (%) | 0/100 | 0/100 | 0/100 | NE | NE | |

| Basal PSA (medium) | 0.4 ng/mL | 0.4 ng/mL | 0.4 ng/mL | 0.05 ng/mL | Surgery + EBRT: 4.9 ng/mL Surgery: 3.3 ng/mL |

|

| Concurrent Hormonotherapy (%) | 0 | 50 | 40 | 33 | Surgery + EBRT: 12.5% Surgery: 50% |

|

| TOXICITY | ||||||

| GU-A | G1: 33% | G1: 37.5% | G1: 40% | G1-2: 25% | G1-2: 12.5% | |

| GI-A | G2: 33% | G1: 37.5% G2: 37.5% |

G1: 33% G2: 7% |

G1-2: 8% | G1-2: 12.5% | |

| GU-T | G3: 33% | G1: 25% G2: 25% G3: 12.5% |

G1: 33% G2: 27% G3: 13% |

G1-2: 12.5% | 0 | |

| GI-T | G2: 66% | G1: 25% G2: 12.5% |

G1: 47% | 0 | 0 | |

Detti et al. described their experience with SBRT for isolated recurrence in the PCa bed, in which 16 patients received 30 Gy in five fractions for re-irradiation or 35 Gy in five fractions for patients without prior radiotherapy treatment. With a median follow-up of 10 months, treatment tolerance was good, and only one patient experienced grade 2 acute genitourinary and gastrointestinal toxicity [33][57].

5. Contribution of Endorectal Devices in Prostate SBRT