Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Mina Händel and Version 2 by Lily Guo.

By utilizing historical changes in Danish legislation related to mandatory vitamin D fortification of margarine, which was implemented in the mid 1930s and abruptly abandoned in June 1985, the studies in the D-tect project investigated the effects of vitamin D on health outcomes in individuals, who during gestation were exposed or unexposed to extra vitamin D from fortified margarine.

- vitamin D

- pregnancy

- fortification

- societal experiment

- public health

- natural experiment

- DOHaD

1. Introduction

Public and environmental health researchers often use societal or natural experiment design studies to explore how unplanned natural or societal events (e.g., epidemics, famines, natural disasters, economic crises) or national policy changes affect health outcomes, or when alternative study designs are not possible or not ethical [1]. Among the most well-known examples of these studies are the Dutch famine studies that investigated the effects of extremely low macro- and micronutrient intake before or during gestation and early in life under famine on health outcomes later in life [2]. During World War II, a part of the Netherlands was cut off from food supplies for five months, resulting in rations below 1000 kcal/day/person. The Dutch famine studies later compared long-term health outcomes in individuals born in this part of the country before, during, or after the period of the famine. The studies utilized a life course approach to explore the role of early life factors on health throughout life. The Early Life Origins of Adult Disease hypothesis, also known as the Developmental Origin of Health and Disease (DOHaD) hypothesis, proposed in the 1930s [3], and later extended by Dubos [4], Widdowson and McCane [5], and Barker [6], was partially based on the results of the Dutch famine studies. Nowadays, attention is being drawn to the importance of prenatal nutrition and its influence on long-term health, examining the effects of specifics nutrients that may program poor health or diseases later in life. Among such nutrients are vitamins, in particular, the fat-soluble vitamin D.

In Denmark, from the mid 1930s and up until June 1985, it was required by law that all margarine products be fortified with vitamin D [7][8][7,8], after which it was abruptly banned. The changes in margarine fortification legislation constituted the basis of the societal experiment design studied in the D-tect project. Specifically, the risk of selected chronic diseases between cohorts of individuals born in Denmark before and after the abrupt change in fortification, and thus prenatally exposed or unexposed (depending on whether it was fortification initiation or cancelation) to extra vitamin D coming from fortified margarine, was compared [9]. While secular trends during 1983–1988 in the health outcomes examined, intake of margarine or the supplementation of vitamin D could have introduced residual confounding, a major strength of the D-tect study design was that factors such as maternal lifestyle, socioeconomy, and demography were in general equally distributed among individuals from both the exposed and the unexposed groups as all individuals were included from closely adjacent birth cohorts around the time of the policy change. Due to the design, where individuals from entire adjacent birth cohorts were examined, unmeasured covariates could be considered to be equally distributed between adjacent exposed and unexposed birth cohorts. Intake of margarine, based on food statistics for purchased margarine, was remarkably stable during the period, as were national policy recommendations for intake and supplementation of vitamin D.

2. Prenatal Vitamin D and the Risk of Type 1 Diabetes

Among the first published studies in the D-tect project were those examining the association between prenatal and first-year-of-life exposure to margarine fortification with vitamin D and the risk of type 1 diabetes (T1D) in children and adolescents [10]. The core date in the societal experiment design was 1 June 1985, when the legislation was issued to stop the mandatory fortification of margarine with vitamin D in Denmark [8]. The dataset was formed from an extract of the Civil Registration System [11][25], containing information on the date of birth and sex of more than 300,000 individuals born in Denmark during 1983–1988, linked to the Danish Registry of Childhood and Adolescence Diabetes [12][26], containing the date of the first diagnosis of verified T1D cases in Denmark (approximately 900 at any time during the study period). Previous studies have documented birth cohort effects for T1D risk (or secular trend) in individuals born in Denmark after 1985 [13][27]. Therefore, the approach of the societal experiment design study for T1D was linear spline regression of the secular trend, with regression cutoff points at the end of fortification and the end of the washout period (i.e., end of fortification plus 15 months); the month and year of birth determined exposure, and logged hazard ratio (HR) for T1D incidence was an outcome. Hypothesizing that changes in the regression line coefficients at the cutoff points would indicate the contribution or lack of fortification to the T1D risk, such changes were investigated, and no changes in T1D risk attributable to the fortification experiment were found. Identifying a relevant time frame for the washout period constituted a methodological challenge, as it was not known how long exactly fortified margarine stayed on the shelf or at people’s homes after the fortification policy changed; 6 months was considered appropriate. The methodological shortcoming of the approach was a short spectrum of investigated birth cohorts (6 years), and consequently, a relatively low number of T1D cases. A larger spectrum of birth cohorts would have allowed us to be more specific about the T1D secular trend changes over the years. Another methodological shortcoming, specific to vitamin D, was that, by this approach, seasonality of birth, essential when investigating environmental vitamin D effects, could not be considered. Another study was conducted to assess the effects of fortification on seasonality of birth in T1D cases, running stratified analyses among exposed (born 1983–1985) and unexposed (born 1986–1988) cohorts, and looking at odds ratios (ORs) for T1D incidence according to the predefined season of birth in males and females [14][11]. First, the ORs for T1D were found to be higher for individuals born in spring compared to that for those born in autumn in unexposed males, which supported the hypothesis, that extra vitamin D from fortified margarine minimized seasonal variation in vitamin D and, therefore, the risk of T1D in boys with late gestation during dark winter months [14][11]. Later, adjustment of regression models with meteorological data of monthly gestational sunshine hours (i.e., the sum of bright sunshine hours during the 9 months before the month of birth) eliminated seasonality of birth difference between exposed and unexposed cohorts of males [14][11]. Analytical simplicity approaching seasonality in the study (i.e., running several logistic regression models differentiated by exposure and sex groups) could be seen as a methodological shortcoming of this study.

3. Prenatal Vitamin D and Birth Weight and Childhood Obesity

Two studies [15][16][12,13] and two commentaries [15][17][12,14] concerning exposure to vitamin D–fortified foods and obesity risk in childhood were published. At the time of performing these studies, the available documentation (i.e., the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Report [18][28]) informed that, a mandatory vitamin D fortification of margarine in Denmark was started in 1961 and canceled in 1985, and a voluntary milk fortification with vitamin D in Denmark was started in 1972 and canceled in 1976 (0.25–0.38 μg vitamin D per 100 g milk). Based on this information, gestation cohorts were composed based on exposure and non-exposure to fortification (i.e., born during two years in or outside the fortification periods). The data on obesity were obtained from the Copenhagen School Health Records Register [19][29], comprising data from the school health examination of 372,636 children who attended schools in Copenhagen from 1936 to 2005. Linear regression modeling for birth weight and body mass index (BMI) at the age of 7, as well as logistic regression modeling for the risk of overweight and obesity at the age of 7, for exposed vs. unexposed, was performed in four analyses sets, i.e., taking into account margarine fortification initiation around 1961, milk fortification initiation around 1972, milk fortification cancelation around 1976, and margarine fortification cancelation around 1985 [15][16][12,13]. The analyses were not adjusted for any covariates except sex, based on the rationale that the individuals in the adjacent exposed and unexposed birth cohorts did not differ by anything but the exposure to vitamin D fortification status. The results of the multiple analyses were inspected for consistency, concluding that vitamin D fortification was not clinically relevant in relation to birth weight, nor did it affect body weight at 7 years [15][16][12,13]. Later, during the D-tect project, the history of margarine and milk fortification with vitamin in Denmark was investigated in detail, consulting multiple historical archived documents [7]. This investigation provided varying data on voluntary milk fortification, could not confirm the year of margarine fortification start (considered as January 1961), and specified the exact date of margarine fortification cancelation (1 June 1985). Even though the updated historical information did not essentially affect the interpretation of the already published results regarding gestational exposure to vitamin D fortification and the risk of childhood obesity, the scientific community was informed about the update of historical information [15][17][12,14]. The advantage of the analytical approach applied was the possibility to run multiple analyses around different time points of fortification change; the disadvantage was the misinformation concerning the history of fortification in the initial discovered historical document, the Nordic Council of Ministers’ Report [18][28].

Additionally, one study investigating seasonality of birth weight was published [20][15]. The study modeled birth weight according to the year and month of birth for the individuals from the Copenhagen School Health Records Register [19][29], born between 1936 and 1989, adjusting for gestational sunshine hours. Thus, this study, even though not addressing the question of fortification, could estimate whether seasonality of birth weight changed during the fortification period. In the case of attenuated seasonality during the fortification period, one could hypothesize that vitamin D from the fortified margarine prevented vitamin D deficiency during dark seasons, which influenced birth weight, and hence, fortification had an effect. Some seasonality patterns for birth weight were identified, which did not coincide with fortification changes. The advantage of the study was the use of the broad spectrum of birth cohorts, allowing the following of trends in birth weight for several decades, and a sophisticated seasonality modeling. The disadvantage of the study in relation to the vitamin D fortification effect analysis was that the modeling did not specifically address fortification.

4. Prenatal Vitamin D and the Risk of Fractures in Late Childhood

One study examined the effect of gestational exposure to vitamin D fortification on the risk of fractures among 10–18-year-old children born in Denmark during 1983–1988 [21][16]. The core date in the design was 1 June 1985, or cancelation of mandatory vitamin D fortification of margarine. Information on the incident and recurrent fractures was obtained from the Danish National Patient Register [22][30], and a multiplicative Poisson regression was used to examine the association between birth cohort and fracture rates in boys and girls, fitting a cohort–period–age model. The risk of fractures was found to be increased among both girls and boys from birth cohorts before 1985 (i.e., the vitamin D fortification termination): the risk ratio (RR) for exposed vs. unexposed girls was 1.15 (95 % CI 1.11, 1.20); for boys 1.11 (95 % CI 1.07, 1.14). When including the period effects in the model (i.e., exposed, washout, unexposed), the association was no longer significant. The potential modification effect (i.e., interaction) by the season of birth was explored and shown to be nonexistent. When stratifying the analyses by fracture site, the results did not change. Additionally, the risk of fractures by age in the chosen birth cohorts was explored. The strength of the cohort–period–age design employed in this study was a detailed exploration of the different aspects of the fracture risk (i.e., by sex, birth cohort, birth period, age, and season of birth), hence maximizing the utilization of the available data. Another important issue was the high validity of fracture diagnoses codes from the Danish National Patient Register, due to the low risk of error when diagnosing fractures by radiology in the hospital setting.

5. Prenatal Vitamin D and the Risk of Gestational Diabetes, Pre-Eclampsia, Childhood Asthma, Adult Celiac Disease, and Inflammatory Bowel Disease

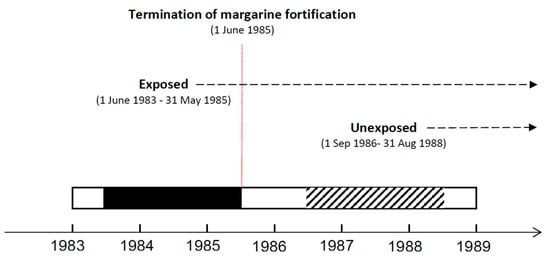

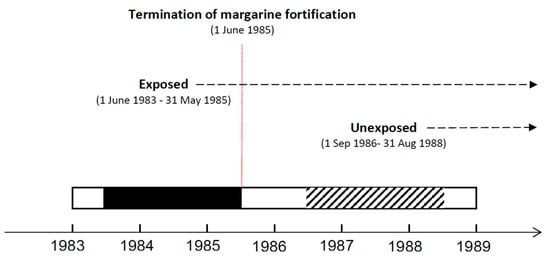

Studies analyzing the effect of gestational exposure to vitamin D fortified margarine on the risk of gestational diabetes [23][17], pre-eclampsia [24][18], childhood asthma [25][20], adult celiac disease [26][21], and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [27][22] later in life were subsequently published. The termination of the Danish fortification program in June 1985 constituted the basis of the study designs in these studies. The risk of the selected outcomes in birth cohorts from two years before (i.e., exposed) and after (i.e., unexposed) the fortification termination, separated by 15 months of washout period, was compared. Exposed and unexposed cohorts were followed for equal amounts of time in the Danish National Patient Register [22][30], to detect specified outcomes (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Design of the studies on fractures, gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia, childhood asthma, adult celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) outcomes.

For gestational diabetes and pre-eclampsia outcomes, the focus was on the first diagnosis of the relevant outcomes in women from the selected cohorts, who gave birth for the first time at age 14–27 years for pre-eclampsia [24][18] or at age 20–27 years for gestational diabetes [23][17]. These women were identified using information from the Danish Medical Birth Register [28][31], where information on covariates (e.g., mother’s smoking during pregnancy and pre-pregnancy BMI, offspring’s gestational age at birth and sex) was also obtained. For asthma outcomes, the focus was on the time of the first inpatient asthma diagnosis admission at age 0–9 years [25][20]. For celiac disease and IBD, the focus was on the first admission with a diagnosis at age 0–30 years [21,22. Due to the design, where individuals from entire adjacent birth cohorts were examined, unmeasured covariates were considered to be equally distributed between adjacent exposed and unexposed birth cohorts. Depending on the type of the outcome (i.e., time to the hospital-based first diagnosis, or the presence of the hospital-based diagnosis), Cox or logistic regression models were run, consequently running stratified analyses considered relevant (e.g., stratified by smoking status during pregnancy for pre-eclampsia [24][18] or by sex for asthma and IBD [25][27][20,22]). The effect of the season of birth was investigated by adjusting the analyses by month of birth (for asthma [25][20]), including exposure and season (or month) of birth interaction into regression modeling (for asthma [25][20], celiac disease [25][20], and IBD [27][22]), or running analyses stratified by season of birth (for gestational diabetes [23][17]). Prenatally exposed women born in spring, when pregnant later in life, had a lower risk of developing gestational diabetes compared to unexposed women born in the same season (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.50, 0.94) [23][17]. Prenatally exposed women, if smoking when pregnant later in life, had a lower risk of developing pre-eclampsia compared to unexposed and smoking women (OR 0.49, 94% CI 0.34, 0.72) [24][18]. A decreased risk for asthma was shown in boys under 3 years of age exposed to the fortification, compared to boys of the same age not exposed to fortification (HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.67, 0.92) with no modification effect by month of birth [25][20]. ORs for developing celiac disease were similar in exposed and unexposed cohorts, with no significant modification effect by season of birth [26][21]. Lower odds of IBD were found for individuals under the age of 30 exposed to the fortification prenatally, compared to individual not exposed (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.79, 0.95), and no significant effect of season of birth was detected [27][22]. The specific feature of these studies was the use of hospital-based diagnoses, thus leaving out mild and moderate asthma cases diagnosed in primary care [25][20] and raising some questions regarding the validity of the gestational diabetes diagnosis [23][17]. Another specific feature of all these studies (except the one on IBD, where the secular trend in disease incidence could partly explain the results [27][22]) was that no secular trends in the incidence of the investigated outcomes were identified in Denmark based on the obtained data from 1983 to 1988. It was not known, however, whether there were any secular changes over the longer period. Moreover, secular changes could occur in alternative exposure sources (i.e., vitamin D intake via food), and potential confounders (e.g., mother’s socioeconomic status, mother’s exposure to infections and physical activity), and the latter was explored if the data was available from the Danish Medical Birth Register [28][31]. The strengths of these studies were their novelty, long follow-ups, and large sample sizes with up to 200,000 individuals.

6. Other Fortification Experiment-Based Studies in the D-Tect Project

Three studies were conducted exploring alternative hypotheses to “gestational exposure to vitamin D vs. health later in life” and utilizing the design of societal experiment with fortification. One study investigated the risk of pre-eclampsia in pregnant women exposed vs. unexposed to fortification; no fortification effect was shown [29][19]. Another study was on the probability of live birth in women with an infertility diagnosis registered in the Danish Infertility Cohort exposed vs. unexposed to fortification. The results showed that infertile women exposed to fortification had an increased chance of live birth compared to women not exposed to fortification [30][23].

Lastly, one study investigated the risk of type 2 diabetes in birth cohorts exposed to different doses of vitamin A from fortified margarine. The change in the dose of vitamin A margarine fortification in Denmark occurred early in 1961 [18][28]. The latter study showed an effect of an extra dose of vitamin A reducing the risk of type 2 diabetes later in life [31][24]. The methodological advantages and shortcomings of all the mentioned studies were similar to those described in the previous section.