Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Bruce Ren and Version 1 by Herbert Schneckenburger.

Relevant samples are described and various problems and challenges—including 3D Challenges of 3D imaging by optical sectioning, light scattering and phototoxicity—are addressed. Furthermore, enhanced methods of wide-field or laser scanning microscopy together with some relevant examples and applications are summarized. In the future one may profit from a continuous increase in microscopic resolution, but also from molecular sensing techniques in the nanometer range using e.g., non-radiative energy transfer (FRET).

- 3D cell cultures

- light scattering

- phototoxicity

- wide-field microscopy

- laser scanning microscopy

- structured illumination

- light sheet microscopy

- FRET

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Experimental and pre-clinical life cell approaches traditionally use two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures, which are easy to establish, but frequently provide results of limited significance, since cells are lacking a physiological microenvironment. In contrast, three-dimensional (3D) cell cultures, e.g., multicellular tumor spheroids (MCTS), maintain tissue-like properties and therefore provide a more realistic background for experimental studies, e.g., screening of pharmaceutical agents [1,2][1][2]. However, imaging of 3-dimensional specimens is challenging, since the sample thickness commonly exceeds the depth of focus of a conventional detection system, and light scattering considerably impairs the image quality. Therefore, methods based on optical sectioning, e.g., confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) [3,4][3][4], Optical Sectioning Structured Illumination Microscopy (OS-SIM) [5], or light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) [6,7][6][7] are applied preferentially. Here, images are recorded plane by plane, and resulting 3D plots are calculated offline. A problem for CLSM related methods as well as for OS-SIM is that for imaging each plane the whole sample has to be illuminated, so that upon recording of the whole specimen phototoxic damages are likely to occur [8]. Furthermore, photobleaching may increase in the course of an experiment and falsify the experimental results. Altogether, 3D imaging creates a large number of data (“big data”), which have to be handled appropriately.

2. 3D Samples

Two-dimensional cell cultures have a well-established protocol in biomedical research and provide a simple, fast, and cost-effective tool for e.g., drug discovery assays. However, mammalian cells commonly grow within a complex three-dimensional microenvironment with a different gene expression and protein synthesis pattern [9]. Therefore, various 3D models have been established to better mimic the natural cell environment.

Cells embedded in hydrogels, e.g., agarose, which are readily accessed by optical sectioning methods like CLSM or OS-SIM may provide more realistic studies of cell morphology, e.g., to examine the influence of mechanical signals on cell behavior [10]. Multicellular (tumor) spheroids have gained significance in preclinical studies, as they appear to be more appropriate for studies of cell physiology, cell metabolism, or tissue diagnostics. 3D cultivation techniques commonly prevent cell attachment to surfaces, using hanging drop methods, liquid overlay methods or agitation-based approaches [11]. Cell cultivation in a solid matrix, e.g., agarose gel, may permit 3D cell growth under realistic conditions [12,13][12][13]. Cell spheroids are generally characterized by an external proliferating region and an internal quiescent zone (caused by the gradient of nutrient and oxygen diffusion), which may surround a necrotic core in larger spheroids [14].

Organoids are a type of 3D cell culture containing organ-specific cells that have been grown from a range of organs, including kidney, breast and liver (for a review see e.g., [15,16][15][16]). However, current 3D systems often lack a vasculature, which might support tissues with oxygen and nutrients, remove waste and build up an immune system. Nevertheless, organoid development is a rapidly growing field, and complex 3D systems including fully vascularized brain organoids [17] or organs-on-a-chip [18] have been reported in recent studies.

Traditionally, biopsies from a histological laboratory are routinely fixed and either embedded in paraffin, or frozen as thin sections, stained and mounted on glass slides. These procedures, however, introduce artifacts and severely limit the information, as only a small fraction of a specimen is used for microscopy. Novel approaches of nondestructive slide-free pathology are investigated, which allow deep volumetric microscopy of whole biopsy specimens [19]. Imaging of whole organisms is an important tool in developmental biology as well as drug screening [20]. Microscopy of small organisms requires either high transparency or the application of optical clearing techniques (see below), if viability is not a main criterion.

Measurements of 3D (cell) cultures often need specific sample holders, e.g., glass or plastic tubes or even micro-capillaries, which may be rotated for multi-view applications (see e.g., [21]).

3. Phenomena and Challenges

3.1. Light Scattering

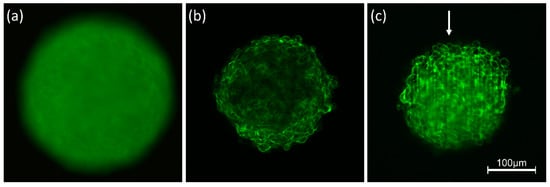

Interaction of light with any kind of samples is described in terms of absorption and scattering. In particular, light scattering experiments with angular or spectral resolution have been used for more than 30 years for characterization of various types of cells [22,23][22][23] or for measurement of morphological changes in cells undergoing necrosis or apoptosis [24,25][24][25]. However, scattering reduces the quality of images due to light attenuation, blurring and a loss of contrast. Obviously, these problems are more severe for three-dimensional than for two-dimensional samples, since scattering does not only occur in a certain plane of detection, but also creates background signals from the whole illuminated volume. This is well documented by Figure 1 showing 3D spheroids of Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells of about 250 µm diameter expressing a membrane-associated Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP). Conventional fluorescence microscopy (Figure 1a) shows a completely blurred image, since information from the focal plane is superposed by out-of-focus images, and since pronounced scattering further reduces the image quality. The impact of scattering appears lower, if individual planes of the sample are selected either by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) or by light sheet fluorescence microscopy (LSFM). Nevertheless, a loss of fluorescence intensity occurs in the central parts of the CLSM image (Figure 1b) and along the direction of light propagation in the LSFM image (Figure 1c). Obviously, light attenuation is less pronounced in the LSFM image, where due to the anisotropy of Mie scattering [26] light is scattered preferentially into forward direction. However, some stripes in the direction of light incidence are often unavoidable. Scattering is becoming lower at higher wavelengths, which are used preferentially in multiphoton microscopy [27,28][27][28].

Figure 1. Spheroids of CHO-pAcGFP1-Mem cells recorded by conventional fluorescence microscopy (a), CLSM (b) and LSFM (c). Single planes are selected in (b,c) at a depth of 60 µm within the spheroid; arrow indicates direction of light incidence in LSFM (excitation wavelength: 488 nm; fluorescence detected at λ ≥ 505 nm).

For reduction of light scattering optical clearing techniques matching the refractive indices of sample and surrounding medium have gained considerable importance. Therefore, these techniques are used increasingly for deep view imaging of skin, brain and other organs [29,30,31][29][30][31]. Currently available optical clearing techniques are not compatible with live cell imaging. However, efforts are being made to find biocompatible solutions, especially for ex-vivo applications [32]. While penetration depths are limited to 100–200 µm in non-cleared samples, they can be even larger than 0.5 mm in cleared samples, permitting e.g., to image entire neuronal networks in mouse brains.

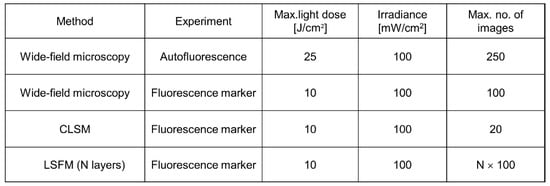

3.2. Phototoxicity, Photobleaching

As reported above, 3D images are often based on optical sectioning, and information is summed up from z-stacks of individual exposures. Only for LSFM, each sectional image results from one illuminated plane, whereas for other wide-field and laser scanning techniques, the whole specimen has to be illuminated for each image section. This implies that light exposure for obtaining a 3D image is summing up and often exceeds the limit of non-phototoxic light doses. Tolerable light doses were determined in a previous manuscript [8] and ranged between 25 J/cm2 (375 nm) and 200 J/cm2 (633 nm) for cultures of native cells, thus increasing with illumination wavelength and corresponding to 4 min. up to about 30 min. of solar irradiance (around 100 mW/cm2). If cells were stained with a fluorescent dye or transfected with a fluorescent protein, typical non-phototoxic light doses were only around 10 J/cm2, corresponding to 100 s of solar irradiance. In Figure 2, a maximum number of images is indicated for the case that cells are illuminated with 100 mW/cm2 (corresponding to 1 nW/µm2) for 1 s (wide-field images) or 5 s (laser scanning image). While only about 20 layers of a 3D cell spheroid can thus be irradiated once by CLSM, each layer can be illuminated about 100 times by LSFM. This favors light sheet microscopy for long-term experiments in cell or developmental biology.

Figure 2. Maximum non-phototoxic light doses and maximum number of images for various methods of 3D live cell imaging. For autofluorescence experiments an excitation wavelength of 375 nm is assumed. An exposure time of 5 s is assumed for LSFM, and a time of 1 s for all other (wide-field) techniques (data partly reproduced from [8]).

In previous studies [33] we found that non-phototoxic light doses did not depend on whether the light was applied continuously or in short pulses. This implies that for multiphoton imaging (see Section 4.1) the integral light dose and the wavelength of illumination appear to be the main limiting factors. Therefore, due to the longer wavelengths phototoxicity is generally lower for multiphoton than for single photon imaging.

Increasing sensitivities of novel detection systems (e.g., ultra-sensitive cameras) will increase the number of images measured at non-phototoxic light doses and will permit recording of fast dynamic processes, e.g., rapid cell migration, membrane or microtubule dynamics, mitochondrial motion as well as endo- or exocytosis.

A further phenomenon upon pronounced light exposure is photobleaching or fluorescence bleaching. This effect may be concomitant with modification or destruction of a specific fluorophore [34] and makes quantitative evaluation of fluorescence signals difficult. In some cases, intersystem crossing to a (non-fluorescent) excited triplet state occurs, and after deactivation of this state the corresponding molecules may fluoresce again (“fluorescence recovery”). This effect often causes characteristic “blinking” and is used in single molecule spectroscopy (for a review see [35]). For more than 40 years “fluorescence recovery after photobleaching” (FRAP) has been applied to measure cell, membrane and, in particular, protein dynamics (for reviews see [36,37][36][37]). In this case, part of a fluorescent specimen is photobleached, and re-diffusion of molecules from outside this part is measured. However, this method should be applied with care since high light exposure may damage living specimens.

3.3. “Big Data”

3D live cell imaging, especially light sheet microscopy of larger specimens, generates large datasets that need to be stored and processed. Multimodal configurations, e.g., time-lapse or multispectral devices, or high-throughput/high-content setups add even more data leading to multidimensional datasets in the gigabyte or even terabyte range [38,39][38][39]. High-end computer hardware and central networks for efficient storage and retrieval of data as well as for fast processing of huge datasets and appropriate data management are needed. Open source software applications, e.g., OME Remote Objects (OMERO), enable access to and use of a wide range of biological data and provide open, flexible solutions for data management [40]. Recently, automated image processing and machine learning have become valuable tools to extract meaningful information from large datasets. As cells can be regarded as highly controlled objects, microscopy is well suited to pattern recognition tools based on neural networks and deep learning [41]. Several commercial (Imaris, Amira, Arivis) as well as non-commercial (BigDataViewer plugin for FIJI/ImageJ [42], ilastik [43]) software applications for high-performance 3D visualization and analysis are available.

References

- Kunz-Schughart, L.A.; Freyer, J.P.; Hofstaedter, F.; Ebner, R. The Use of 3-D Cultures for High-Throughput Screening: The Multicellular Spheroid Model. J. Biomol. Screen. 2004, 9, 273–285.

- Wittig, R.; Richter, V.; Wittig-Blaich, S.; Weber, P.; Strauss, W.S.L.; Bruns, T.; Dick, T.-P.; Schneckenburger, H. Biosensor-expressing spheroid cultures for imaging of drug-induced effects in three dimensions. J. Biomol. Screen. 2013, 18, 736–743.

- Pawley, J. Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy, 3rd ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 1990.

- Webb, R.H. Confocal optical microscopy. Rep. Prog. Phys. 1996, 59, 427–471.

- Neil, M.A.; Juskaitis, R.; Wilson, T. Method of obtaining optical sectioning by using structured light in a conventional microscope. Opt. Lett. 1997, 22, 1905–1907.

- Pampaloni, F.; Chang, B.-J.; Stelzer, E.H.K. Light sheet-based fluorescence microscopy (LSFM) for the quantitative imaging of cells and tissues. Cell Tissue Res. 2015, 362, 265–277.

- Santi, P.A. Light sheet fluorescence microscopy: A review. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 2011, 59, 129–138.

- Schneckenburger, H.; Weber, P.; Wagner, M.; Schickinger, S.; Richter, V.; Bruns, T.; Strauss, W.S.L.; Wittig, R. Light exposure and cell viability in fluorescence microscopy. J. Microsc. 2012, 245, 311–318.

- Bardsley, K.; Deegan, A.J.; El Haj, A.; Yang, Y. Current State-of-the-Art 3D Tissue Models and Their Compatibility with Live Cell Imaging. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 1035, 3–18.

- Cambria, E.; Brunner, S.; Heusser, S.; Fisch, P.; Hitzl, W.; Ferguson, S.J.; Wuertz-Kozak, K. Cell-laden agarose-collagen composite hydrogels for mechanotransduction studies. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 346.

- Lazzari, G.; Couvreur, P.; Mura, S. Multicellular tumor spheroids: A relevant 3D model for the in vitro preclinical investigation of polymer nanomedicines. Polym. Chem. 2017, 8, 4947–4969.

- Johnson, M.D.; Bryan, G.T.; Reznikoff, C.A. Serial cultivation of normal rat bladder epithelial cells in vitro. J. Urol. 1985, 133, 1076–1081.

- Dusny, C.; Grünberger, A.; Probst, C.; Wiechert, W.; Kohlheyer, D.; Schmid, A. Technical bias of microcultivation environments on single cell physiology. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 1822–1834.

- Edmondson, R.; Broglie, J.J.; Adcock, A.F.; Yang, L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. Assay Drug Dev. Technol. 2014, 12, 207–218.

- Van Ineveld, R.L.; Ariese, H.C.R.; Wehrens, E.J.; Dekkers, J.F.; Rios, A.C. Single-Cell Resolution Three-Dimensional Imaging of Intact Organoids. J. Vis. Exp. 2020, 5.

- Torres, S.; Abdullah, Z.; Brol, M.J.; Hellerbrand, C.; Fernandez, M.; Fiorotto, R.; Klein, S.; Königshofer, P.; Liedtke, C.; Lotersztajn, S.; et al. Recent Advances in Practical Methods for Liver Cell Biology: A Short Overview. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2027.

- Mansour, A.A.; Gonçalves, J.T.; Bloyd, C.W.; Li, H.; Fernandes, S.; Quang, D.; Johnston, S.; Parylak, S.L.; Jin, X.; Gage, F.H. An in vivo model of functional and vascularized human brain organoids. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 432–441.

- Schneider, O.; Zeifang, L.; Fuchs, S.; Sailer, C.; Loskill, P. User-Friendly and Parallelized Generation of Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Microtissues in a Centrifugal Heart-on-a-Chip. Tissue Eng. Part A 2019, 25, 786–798.

- Glaser, A.K.; Reder, N.P.; Chen, Y.; McCarty, E.F.; Yin, C.; Wei, L.; Wang, Y.; True, L.D.; Liu, J.T.C. Light-sheet microscopy for slide-free non-destructive pathology of large clinical specimens. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 1, 0084.

- Martinez, N.J.; Titus, S.A.; Wagner, A.K.; Simeonov, A. High-throughput fluorescence imaging approaches for drug discovery using in vitro and in vivo three-dimensional models. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 1347–1361.

- Bruns, T.; Schickinger, S.; Schneckenburger, H. Sample holder for axial rotation of specimens in 3D Microscopy. J. Microsc. 2015, 260, 30–36.

- Brunstin, A.; Mullaney, P.F. Differential Light-Scattering from Spherical Mammalian Cells. Biophys. J. 1974, 14, 439–453.

- Mourant, J.R.; Johnson, T.M.; Doddi, V.; Freyer, J.P. Angular dependent light scattering from multicellular spheroids. J. Biomed. Opt. 2002, 7, 93–99.

- Mulvey, C.S.; Sherwood, C.A.; Bigio, I.J. Wavelength-dependent backscattering measurements for quantitative real-time monitoring of apoptosis in living cells. J. Biomed. Opt. 2009, 14, 064013.

- Mulvey, C.S.; Zhang, K.; Bobby Liu, W.H.; Waxman, D.J.; Bigio, I.J. Wavelength-dependent backscattering measurements for quantitative monitoring of apoptosis, part 2: Early spectral changes during apoptosis are linked to apoptotic volume decrease. J. Biomed. Opt. 2011, 16, 117002.

- Bohren, C.F.; Huffman, D.R. Absorption and Scattering of Light by Small Particles; Wiley-Interscience Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1998.

- König, K. Multiphoton microscopy in life sciences. J. Microsc. 2000, 200 Pt 2, 83–104.

- Miller, D.R.; Jarrett, J.W.; Hassan, A.M.; Dunn, A.K. Deep Tissue Imaging with Multiphoton Fluorescence Microscopy. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2017, 4, 32–39.

- Costa, E.C.; Silva, D.N.; Moreira, A.F.; Correia, I.J. Optical clearing methods: An overview of the techniques used for the imaging of 3D spheroids. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2019, 116, 2742–2763.

- Sdobnov, A.Y.; Lademann, J.; Darvin, M.E.; Tuchin, V.V. Methods for Optical Skin Clearing in Molecular Optical Imaging in Dermatology. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2019, 84 (Suppl. S1), S144–S158.

- Susaki, E.A.; Tainaka, K.; Perrin, D.; Yukinaga, H.; Kuno, A.; Ueda, H.R. Advanced CUBIC protocols for whole-brain and whole-body clearing and imaging. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 1709–1727.

- Costantini, I.; Cicchi, R.; Silvestri, L.; Vanzi, F.; Pavone, F.S. In-vivo and ex-vivo optical clearing methods for biological tissues: Review. Biomed. Opt. Express 2019, 10, 5251–5267.

- Schneckenburger, H.; Richter, V.; Wagner, M. Live-Cell Optical Microscopy with Limited Light Doses; SPIE Spotlight Series; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; Volume 42, p. 38.

- Song, L.; Hennink, E.J.; Young, I.T.; Tanke, H.J. Photobleaching Kinetics of Fluorescein in Quantitative Fluorescence Microscopy. Biophys. J. 1995, 68, 2588–2600.

- Moerner, W.E.; Shechtman, Y.; Wang, Q. Single-molecule spectroscopy and imaging over the decades. Faraday Discuss. 2015, 184, 9–36.

- Ishikawa-Ankerhold, H.C.; Ankerhold, R.; Drummen, G.P. Advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques–FRAP, FLIP, FLAP, FRET and FLIM. Molecules 2012, 17, 4047–4132.

- Lippincott-Schwartz, J.; Snapp, E.L.; Phair, R.D. The Development and Enhancement of FRAP as a Key Tool for Investigating Protein Dynamics. Biophys. J. 2018, 115, 1146–1155.

- Amat, F.; Höckendorf, B.; Wan, Y.; Lemon, W.C.; McDole, K.; Keller, P.J. Efficient processing and analysis of large-scale light-sheet microscopy data. Nat. Prot. 2015, 10, 1679–1696.

- Reynaud, E.G.; Peychl, J.; Huisken, J.; Tomancak, P. Guide to light-sheet microscopy for adventurous biologists. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 30–34.

- Allan, C.; Burel, J.M.; Moore, J.; Blackburn, C.; Linkert, M.; Loynton, S.; MacDonald, D.; Moore, W.J.; Neves, C.; Patterson, A.; et al. OMERO: Flexible, model-driven data management for experimental biology. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 245–253.

- Orth, A.; Schaak, D.; Schonbrun, E. Microscopy, Meet Big Data. Cell Syst. 2017, 4, 260–261.

- Pietzsch, T.; Saalfeld, S.; Preibisch, S.; Tomancak, P. BigDataViewer: Visualization and processing for large image data sets. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 481–483.

- Berg, S.; Kutra, D.; Kroeger, T.; Straehle, C.N.; Kausler, B.X.; Haubold, C.; Schiegg, M.; Ales, J.; Beier, T.; Rudy, M.; et al. ilastik: Interactive machine learning for (bio)image analysis. Nat. Methods 2019, 16, 1226–1232.

More