Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) represents an early form of thyroid dysfunction and is biochemically defined as an elevated TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone or thyrotropin) level with a normal level of free thyroxine (FT4) within the reference range. SCH can affect about 1–11% of adults depending on the cohort studied, and such wide variability in its incidence can be attributed to the environmental and ethnic differences as well as the different TSH reference ranges used in each country.

- subclinical hypothyroidism

- thyroid

- hypertension

- blood pressure

- females

- meta-analysis

1. Introduction

Subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH) represents an early form of thyroid dysfunction and is biochemically defined as an elevated TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone or thyrotropin) level with a normal level of free thyroxine (FT4) within the reference range [1]. SCH can affect about 1–11% of adults depending on the cohort studied, and such wide variability in its incidence can be attributed to the environmental and ethnic differences as well as the different TSH reference ranges used in each country [2][3][4][5][6][7][8][2,3,4,5,6,7,8].

The cardiovascular system is one of the most important downstream targets of triiodothyronine (T3), the active cellular form of thyroid hormone. Despite its relatively benign clinical course compared to an overt hypothyroidism, SCH has been found to be associated with an increased cardiovascular risk, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, stroke, and dyslipidemia [9][10][11][9,10,11]. However, there is no clear consensus on the relationship between SCH and hypertension (HTN), with several published studies showing a positive association between SCH and HTN [12][13][14][15][16][17][12,13,14,15,16,17] and some studies showing no association [18][19][20][18,19,20].

As in most thyroid diseases, it has been reported that the incidence of SCH is more common in women than in men [17][21][22][23][17,21,22,23]. Moreover, the prevalence of SCH in both genders increases with age, and 8% to 18% of adults 65 years of age or older was found to have SCH [22][24][25][22,24,25]. For this reason, we decided to study a female patient population and examine different age groups.

The aim of this study was to elucidate the relationship between SCH and HTN in females via meta-analysis of published cross-sectional and cohort studies. Moreover, we also divided the included studies into the middle-aged (mean age < 65) and the older (mean age ≥ 65) subgroups and sought to investigate the effect of age on the association between SCH and HTN.

2. Analysis on Results

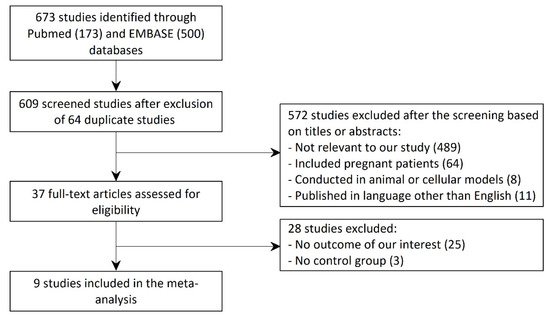

Figure 1 shows a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram that depicts the process of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion or exclusion of the studies. The initial search of the PubMed and the EMBASE databases yielded 673 articles (173 studies from PubMed and 500 studies from EMBASE). After exclusion of 64 duplicate studies, 609 studies underwent title and abstract review. Of these articles, 572 studies were excluded because they were not relevant to our study ( n = 489), included pregnant patients ( n = 64), were conducted in animal or cellular models ( n = 8), or published in a language other than English ( n = 11). A total of 37 articles underwent full-length review. Of these, 28 studies were excluded as they did not have the outcome of our interest ( n = 25) or did not have a control group ( n = 3). Thus, the final analysis included 9 unique studies with total of 21,972 female subjects.

The main characteristics of the included studies ( n = 9) are described in Table 1 . Comorbidities other than HTN in patients with SCH included metabolic syndrome, hyperlipidemia, and impaired fasting glucose. Regarding the study design, five studies were cross-sectional, three studies were prospective cohort, and one was a case cohort. For each study, information including the number of participants, the mean and the reference TSH level of the SCH group, and the reference blood pressure level for HTN was given.

| Author | Country | Published Year | Study Type | SCH (HTN(a)/ No HTN(b)) (1896) |

Control (HTN(c)/ No HTN(d)) (20,076) |

Mean Age | Odds Ratio (95% CI) |

Mean (Reference) TSH Level in SCH (mIU/L) |

HTN SBP/DBP (mmHg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashizawa ° | Japan | 2010 | Cross- Sectional |

194 (110/84) |

2134 (1253/881) |

71.5 | NR | 5.98 (>4.5) |

>140/90 |

| Harada | U.S. | 2017 | Prospective Cohort |

573 (167/406) |

2571 (694/1877) |

56.9 | NR | NR (>4.2) |

>130/85 |

| Legrys ° | U.S. | 2013 | Case Cohort |

282 (85/197) |

3381 (995/2386) |

67.5 | NR | 5.85 (>4.68) |

NR |

| Lindeman ° | U.S. | 2003 | Cross- Sectional |

74 (27/47) |

283 (113/170) |

73.9 | NR | NR (>4.7) |

>160/95 |

| Liu, Hwang | Taiwan | 2018 | Cross- Sectional |

102 (45/57) |

6323 (2257/4066) |

48.5 | NR | NR (>5.5) |

>130/85 |

| Liu, Jiang | China | 2010 | Cross- Sectional |

75 (31/44) |

724 (185/539) |

44.8 | NR | 6.8 (>4.8) |

>140/90 |

| Luboshitzky Aviv |

Israel | 2002 | Prospective Cohort |

57 (11/46) |

34 (1/33) |

46.8 | NR | 10 (>4.5) |

>140/90 |

| Luboshitzky Herer |

Israel | 2004 | Prospective Cohort |

44 (15/29) |

9 (4/15) |

51.6 | NR | 9.2 (>4.5) |

>140 |

| Zhang | China | 2019 | Cross- Sectional |

495 | 4607 | 48.8 | 1.959 (1.594, 2.407) |

NR (>5.0) |

>140/90 |

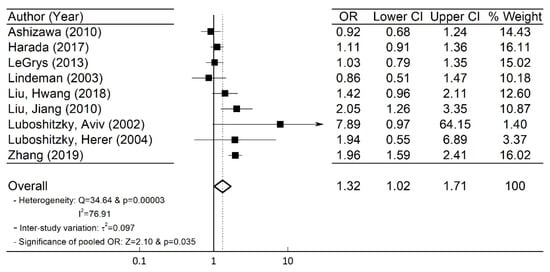

A total of nine ( n = 9) studies with 21,972 female subjects (1896 subjects with SCH) were included in our meta-analysis. Using the information in Table 1 for the number of subjects in the SCH and control groups with or without HTN, we obtained the OR and its corresponding 95% CI [26][27]. The forest plot in Figure 2 depicts the OR and the 95% CI of individual study. Heterogeneity among the included studies existed as the Q-statistic, and its corresponding p -values were 34.64 and 0.00003, respectively. We also quantified the degree of heterogeneity by using the I 2 statistic, which indicated a high heterogeneity among the studies (I 2 = 76.91%). Thus, in our study, we employed the random-effects model [26][27][27,28] and obtained the overall pooled OR (=1.32) and 95% CI (=1.02–1.71) as shown in Figure 2 .

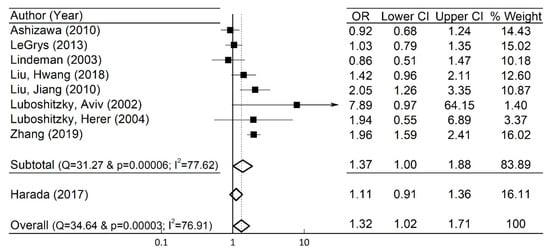

To examine the robustness of the pooled OR and 95% CI in the whole group, sensitivity analyses were undertaken by excluding an individual study at a time, and they showed no significant changes. For instance, when the study of Harada et al. [12] was arbitrarily excluded, the pooled OR (=1.37), and the 95% CI (=1.00–1.88) were close to those in the original whole group ( Figure 34 ).

3. CDiscurrent Insightsssion

First, we discuss the increased incidence of HTN in patients with SCH. Under normal physiological circumstances, thyroid hormone affects the blood pressure via its action on the ion channels, inducing endothelium-mediated nitric-oxide production and causing direct vascular smooth muscle relaxation [28][29][31,32]. Endothelial dysfunction secondary to impaired vascular smooth muscle relaxation have previously been demonstrated in SCH, which may explain the increased incidence of HTN [30][31][33,34]. We also note that thyroid hormone plays an essential role in removing excess LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol [32][35]. Accordingly, patients with SCH have been shown to have an increased incidence of hyperlipidemia, which likely contributes to atherosclerosis, increased arterial stiffness, and HTN [32][33][35,36].

In our study, the discrepant association of SCH and HTN in different age subgroups is notable; there was no statistically significant association between SCH and HTN in the older subgroup unlike in the middle-aged subgroup. The reason behind this discrepancy is unclear, but several suggestions can be made. Notably, the activity of type II iodothyronine deiodinase, an enzyme that converts pro-hormone thyroxine (T4) to an active thyroid hormone (T3) in target cells, has been shown to decrease with aging [25]. This in turn leads to a decreased T3 level and a reflexive increase in TSH level in older people. Indeed, in cross-sectional studies of euthyroid individuals, TSH concentrations have been shown to increase with age [34][35][36][37,38,39]. Moreover, several cohort studies have shown that the age-associated increase in TSH concentrations did not cause a decrease in free T4, suggesting a change in TSH set-point with aging [37][38][40,41]. Hence, age-related TSH elevation in the older subgroup may be more representative of a physiological aging process than a pathologic condition. In a randomized controlled trial for thyroid hormone replacement for untreated older adults with SCH, it was shown that the levothyroxine therapy in the elderly patients diagnosed with SCH provided no symptomatic benefit [39][42]. Moreover, it has been shown that elderly patients diagnosed with SCH under current guidelines do not strongly express the clinical signs of hypothyroidism compared to younger SCH patients, and this may further support the inadequacy of using the same guidelines for diagnosing SCH in the elderly population [8]. Ultimately, we must be cautious when diagnosing and treating SCH in older patients, and a guideline for age-based reference range of TSH is needed.

We also reference a previous work that investigated the association between SCH and the blood pressure [40][43]. This study was a meta-analysis that aimed to obtain the pooled weighted mean difference (WMD) of blood pressure in SCH versus the euthyroid groups. In contrast to our work, the subjects in the study consisted of both males and females. In this work, SCH was found to be associated with a slightly higher systolic blood pressure (SBP) than the euthyroid group (pooled WMD of SBP = 1.47 mmHg, 95% CI = 0.54–2.39, p = 0.002), while there was no statistically significant difference in diastolic blood pressure (DBP) between the SCH and the euthyroid groups. Moreover, a meta-regression analysis showed a significant linear relationship between age difference and WMD of SBP in the SCH and euthyroid groups. Thus, the age difference between the two groups could be a key confounding factor for WMD of SBP. Accordingly, it was concluded that SCH was associated with a slightly higher SBP, which could be attributed to the age difference between the SCH and euthyroid groups. It is important to note that the meta-analysis investigated the relationship between SCH and the mean values of SBP and DBP, but the blood pressures were not necessarily in the hypertensive range. In contrast, our paper studied the association of SCH and the incidence of HTN and a pathologic increase in blood pressures and assessed the pooled OR for the incidence of HTN. To our best knowledge, there is no published meta-analysis that studied the association between SCH and HTN.

Finally, we discuss relevant limitations in our study. In the present study, we focused on the association between SCH and HTN in women, as the incidence of SCH is more common in women. However, in future studies, it would be interesting to examine whether the same association between SCH and HTN is present in the male population also. Secondly, since all the included studies are observational, the meta-analysis might be affected by confounding factors, and hence, the results must be carefully interpreted even though they may provide useful information. Secondly, owing to our inclusion criteria, publication bias may not be completely excluded, as unpublished studies were not included. Thirdly, the TSH cut-off reference level for the SCH and the reference level of HTN varied depending on included studies, which might also affect overall interpretation. Nevertheless, our sensitivity analysis showed unaltered outcomes, which suggested that the overall analysis is robust. Lastly, most of the included studies (except for the work of LeGrys et al. [19], with minimum five-year follow-up) measured their data points for TSH and blood pressures at a single time point, which may lead to less accurate and robust diagnoses of SCH and HTN. In the future, observational studies with longer follow-up periods are needed to establish stronger evidence for the cause and effect relationship between SCH and HTN.