Information campaigns and legal regulation are commonly applied tools to effect change of food consumption habits towards carbon-friendly eating patterns. To develop these, businesses and legislators need to identify consumers’ motivational and emotional antecedents for carbon-friendly food consumption practices. The theory of planned behavior (TPB: attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control), complemented by positive and negative emotions is suitable to predict carbon-friendly food purchases. It serves as excellent framework to develop recommendations for information campaigns and legislation to foster carbon-friendly food purchases.

- carbon-friendly food

- theory of planned behavior

- emotions

1. Carbon-Friendly Food Purchasing

1.1. Definition of carbon-friendly food

2

2

2 emissions [1][2]. (b) Another aspect essential for CO

2

2 in the production process, unlike processed food, such as frozen pizza or microwave dinners [2], which are responsible for much more CO

2

2 than food transported long distances in a chilled or even frozen state [1]. (d) A final aspect of CO

2

2 emissions are produced. Thus, no packaging would be optimal for all food items. Nevertheless, this is not always possible because of legal hygiene standards, e.g., meat needs to be wrapped [3]. This is a rather long and diverse list of how carbon-friendly food can be defined.

2

1.2. Drivers of carbon-friendly food purchase

2 on the climate and the concern regarding the risk of climate change could be predictors for the willingness to spend more money on carbon-friendly food [4]. The surprising finding was that neither knowledge nor concerns significantly impact paying extra for carbon-friendly food. Thus, being aware of the problem is not sufficient to change consumer behavior. Other predictors could be different values, attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control. Aertsens et al. [5] collected research on the drivers of consumers who were purchasing organic food, and found that values such as security, hedonism, universalism, benevolence, stimulation, self-direction and conformity, when linked to organic food, positively impacted attitudes towards the purchase of organic food. Additionally, they showed that these attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control influenced the purchase and consumption of organic food. Thus, personal factors such as values, attitudes and perceived behavioral control definitely affect organic food purchase behavior. Therefore, labeling products as carbon-friendly might stimulate specific values, attitudes and social norms that stimulate consumers to buy carbon-friendly food. Studies [6][7] found a clear connection between labels for carbon-friendly food and the willingness to purchase such food items. Thus, a variety of different drivers to purchase carbon-friendly food has already been researched. Whereas some drivers are effective (personal aspects such as values, attitudes and social norms; labels), others do not impact purchase behavior (knowledge on climate change, concern regarding climate change).

Although some drivers for carbon-friendly food purchases have been identified by now, thus far the psychological process has not been fully detected. While values, attitudes, social norms and perceived behavioral control are psychological factors that have an impact, other psychological determinates of carbon-friendly food purchase are missing. As consumer research [8] shows, consumers’ emotions have a significant effect on purchase behavior. Thus, why should consumers’ emotions not also determine the purchase of carbon-friendly food? A preliminary empirical study indicates that emotions play a role in purchasing organic food [9].

2. Theory of Planned Behavior

The theory of planned behavior (TPB [10]) is often applied in consumer behavior research that bases purchase decisions on three main determinants: attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control towards the purchase. These determinates again result in the intention to purchase, which finally ends in the actual purchase. While this theory was originally developed to explain the influence of significant others as a social-psychological theory, it was adopted by consumer research and used to explain purchase behavior of different kinds [10][11][12][13][14].

Describing the three determinants, the theory of planned behavior [10] postulates that attitudes towards a certain behavior—in our case, the purchase of carbon-friendly food—are the evaluations of the behavior as positive or negative [15]. Thus, some consumers believe that buying carbon-friendly food is a vital behavior that needs to be undertaken to slow down climate change. In contrast, other consumers think that buying carbon-friendly food is a waste of money because climate change is not man-made and, for that reason, cannot be detained by humans. Thus, while the first consumers positively evaluate the purchase of carbon-friendly food, the second ones think of the same behavior negatively.

These three determinants (attitudes, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control) influence the intention to undertake the respective behavior [15]. The intention to undertake a certain behavior is seen as a person’s motivation to undertake the behavior. With carbon-friendly food purchases, the intention, i.e., motivation, is the driver to actually buy carbon-friendly food, go to the shop and actively look for food that is low in CO

2

In summary, the theory of planned behavior is an excellent theory to predict the purchase of carbon-friendly food [11], nevertheless one important aspect seems to be missing in this theory, i.e., emotions [16], to precisely predict carbon-friendly food purchases.

3. Emotions

Emotions are defined as “a mental state of readiness that arises from cognitive appraisals of events or thoughts; is accompanied by physiological processes; is often expressed physically (e.g., in gestures, posture, facial features); and may result in specific actions to affirm or cope with the emotion, depending on its nature and meaning for the person having it” [17] (p. 184). Therefore, emotions are an important psychological determinant of decision-making, thus also in deciding to purchase carbon-friendly food. Nevertheless, there are several taxonomies of emotions [18][19], for instance the list of emotions in social psychology [20].

This list of emotions differentiates between primary, secondary and tertiary emotions [20], whereby a number of emotions on the tertiary level (e.g., arousal, desire, lust, passion, infatuation) comprises one emotion on the secondary level (e.g., lust) and similarly, a number of emotions on the secondary level (e.g., affection, lust, longing) comprises one emotion on the primary level (e.g., love). For all emotions on the primary and secondary level [20], see

Table 1, following other research in consumer behavior that highlights this systematization [21][22].

Table 1. Primary and secondary emotions [20].

| Negative Emotions | Positive Emotions | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Emotion | Secondary Emotion | Primary Emotion | Secondary Emotion |

| Anger | Irritation | Love | Affection |

| Exasperation | Lust | ||

| Rage | Longing | ||

| Disgust | Joy | Cheerfulness | |

| Envy | Zest | ||

| Torment | Contentment | ||

| Sadness | Suffering | Pride | |

| Sadness | Optimism | ||

| Disappointment | Enthrallment | ||

| Shame | Relief | ||

| Neglect | Surprise | Surprise | |

| Sympathy | |||

| Fear | Horror | ||

| Nervousness |

Although the various taxonomies differentiate between many different emotions [20][18], some taxonomies fall back on a simple differentiation between positive and negative emotions [19]. Although we value the fact of being able to differentiate between various qualities of emotions, we also summarize the six primary emotions [20] into negative (sadness, anger, fear) and positive emotions (joy, surprise, love). We consider the different characteristics of these six emotions but reduce the complexity of dealing with their manifoldness.

Earlier research has already focused on specific emotions regarding sustainable consumer behavior. For instance, guilt as a negative emotion was investigated in the context after the consumption [23], showing that the consumption of unsustainable products can stipulate guilt in consumers. Contrarily, the consumption of sustainable products can provoke the positive emotion of pride [23]. Although research on the impact of emotions on the purchase and consumption of sustainable products exists, to our knowledge, studies on the impact of manifold emotions on carbon-friendly food are scarce.

4. Theory of Planned Behavior & Emotions

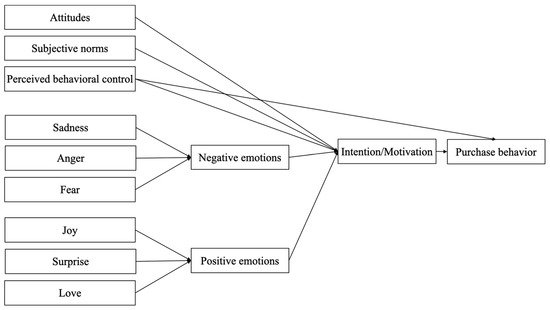

Eventually, we suggest to take the theory of planned behavior [TPB, 20] and adjust it with additional variables, namely negative and positive emotions [20]. As earlier research [16] has identified, although the TPB [10] is a very comprehensive social-psychological theory excellently predicting behavior, it is missing one essential aspect: the state of emotions when humans consider undertaking a behavior. A meta-analysis [24] shows that the incorporation of emotions enhances the predictive power of the TPB [10]. This is the reason why we base our theoretical model on the TPB [10] and emotions [20].

Earlier research [25][26] did incorporate emotions; specifically, the emotions of regret or fear, in the TPB [10] to explain sustainable food-related behavior, i.e., purchasing organic food or selecting an eco-friendly restaurant. However, to our knowledge, the whole range of emotions was never incorporated. Furthermore, emotions were shown to affect purchasing intentions for organic food [9] but independently from the TPB [10]. Nevertheless, carbon-friendly food purchases incorporate more than only the purchase of organic food. For that reason, we not only incorporate a whole range of emotions [20] in the TPB [10], but also investigate the predictors of the comprehensive behaviors of carbon-friendly food purchases, i.e., plant-based diet instead of animal products, more organic food but less processed food, preferring local food over chilled or frozen food and no or minimal packaging. Based on all these considerations, we formulated the following research questions:

- What are the motivations to purchase carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 2: Which emotions emerge with the purchase of carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 3: Can the theory of planned behavior [5], including negative and positive emotions, explain the purchase of carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 1: What are the motivations to purchase carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 2: Which emotions emerge with the purchase of carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 3: Can the theory of planned behavior [10], including negative and positive emotions, explain the purchase of carbon-friendly food?

-

Research Question 1:

Figure 1 illustrates the proposed relationships that will be tested in our studies. Starting with the TPB [10] and incorporating positive and negative emotions [20], the model is supposed to explain comprehensively different kinds of carbon-friendly food purchases.

Figure 1. Theoretical model including emotions [20] in the TPB [10].

5. Findings & Discussion

To answer Research Question 1 and Research Question 2, two qualitative studies were conducted.

In the first study, regarding the motivations, we found that ethical concerns and personal health are the main drivers for carbon-friendly food consumption. In particular, food production, for instance, of meat, and the effects of food on consumers seemed to be central. In contrast, the environmental aspect was mentioned only as a consequence of other aspects. In addition, consumers also reported negative emotions.

Therefore, the goal of Study 2 was to identify different emotions that relate to carbon-friendly food consumption. This extends previous research that focused on selected emotions with regard to sustainable consumption. Our results show that positive and negative emotions can be evoked regarding carbon-friendly food. Using pictorial material, consumers reported the positive emotion

joy

and related emotions. They were caused by realizing the variety and quality of fresh products available, and how enjoyable producing and preparing one’s own food can be. The main negative emotion discussed was

sadness

, and it was felt in relation to the consequences of industries’ or consumers’ behaviors on the environment. These feelings also included

guilt

or

shame

, two commonly investigated emotions. Overall, the variety of emotions and their causes revealed the importance of identifying them. For instance, the way food is produced and handled can cause positive and negative emotions. Consumer-felt control over their diet and food choice leads to positive emotions. In addition, business practices evoke consumers’ emotions, which may become influential in purchase situations.

Consequently, Research Question 3 tested whether the theory of planned behavior [27], including negative and positive emotions [28], can explain the purchase of carbon-friendly food. We conducted a survey with a representative sample in Austria and found significant influences of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, as well as both negative and positive emotions, on the intention and subsequent purchase of carbon-friendly food. This means that consumers, in general, would purchase carbon-friendly food; they view it as something meaningful.

Consequently, Research Question 3 tested whether the theory of planned behavior [5], including negative and positive emotions [7], can explain the purchase of carbon-friendly food. We conducted a survey with a representative sample in Austria and found significant influences of attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioral control, as well as both negative and positive emotions, on the intention and subsequent purchase of carbon-friendly food. This means that consumers, in general, would purchase carbon-friendly food; they view it as something meaningful.

Regarding consequences for informational campaigns, we conclude that using emotions, preferably positive emotions, in communication with consumers will influence their intention to purchase carbon-friendly food. From a more legal and regulative perspective, we found that consumers’ perceived behavioral control affects their intention and purchase behavior. Thus, the more consumers feel that they can make a difference and choose, the higher the likelihood of their carbon-friendly food purchase. Factual information, in the form of labels or packaging would help consumers learn which products are actually carbon-friendly to make their choice.