Endometrial infections are a common cause of reproductive loss in cattle. Accurate diagnosis is important to reduce the economic losses caused by endometritis. A range of sampling procedures have been developed which enable collection of endometrial tissue or luminal cells or uterine fluid. However, as these are all invasive procedures, there is a risk that sampling around the time of breeding may adversely affect subsequent pregnancy rate.

- cattle

- cotton swab

- endometrial biopsy

- cytobrush

- cytotape

- uterine lavage

1. Introduction

High reproductive performance in production animals such as beef and dairy cattle is vital for achieving optimal per capita return. Endometritis is a common cause of reproductive failure, especially in dairy cattle, causing increases in both calving to conception interval and culling rates [1,2][1][2]. Therefore, detection of endometritis in individual cows, before breeding or embryo transfer (ET), is critical.

Histological changes to the endometrium, such as the increased presence of inflammatory cells in subclinical endometritis, can only be detected by cytology or histopathology [11][3]. Hence, more invasive sample collection methods such as uterine lavage (UL), intrauterine cotton swab (CS) These techniques enable the collection of epithelial and inflammatory cells (CS, UL, CB, and CT), luminal secretions (UL), and endometrial tissue (EB) that allow the inspection of deeper physiological and cellular responses not yet identifiable by routine clinical examinations. The samples obtained can be subjected to cytological examination [12[4][5],13], bacteriological culture [14][6], histopathological examination [15][7], protein analysis [16][8], and gene expression analysis [17][9] to diagnose the status of the endometrial environment.

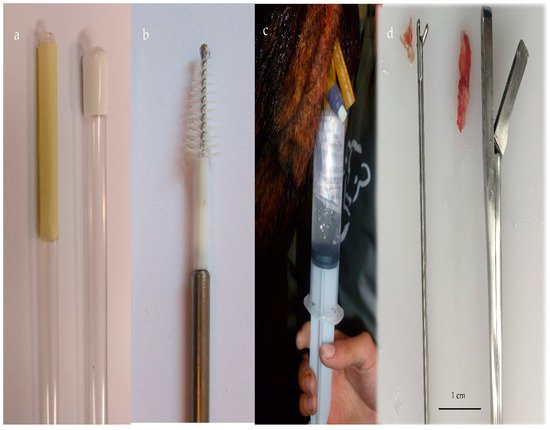

Collectively, these methods involve a transvaginal device being inserted through the cervix (using per rectal manipulation) into the uterine body or uterine horns to collect the sample required (Figure 1). Briefly, for UL, a sterile catheter is introduced into the uterine horn and 20–50 mL of sterile 0.9% sodium chloride solution is infused, and then after per rectal massage of the uterine horns, the saline is aspirated [7,18][10][11]. For EB, the device is guided into the uterine horn, the forceps jaws are then opened and a section of the uterine wall is gently pushed into the jaw and closed [15,22][7][12]. Recently, a new sampling device that allows the collection of endometrial cells, tissue, and uterine secretions after a single passage through the cervix has been developed [23][13].

Figure 1. (a) Cytotape (Credit: Osvaldo Bogado Pascottini), (b) cytobrush, (c) uterine lavage with a saline solution using a Foley catheter, and (d) endometrial tissue with two biopsy devices.

The degree of endometrial injury and trauma varies with the method of sampling from likely to negligible for UL, CS, CB, and CT, to potentially moderate damage when performing EB. EB involves the collection of a full-thickness section of the endometrium, and in some cases a portion of the underlying myometrium (depth of tissue varies from 0.4 to 1 cm) In mares [25][14] and women [26][15], endometrial sampling is a routine procedure which does not apparently adversely affect the likelihood of the sampled female becoming pregnant.

2. Endometrial Sampling Procedures and Pregnancy Rate of Cattle

2.1. Uterine Lavage Studies

Cheong et al. [18][11] performed a prospective cohort study comparing the effect of UL to collect endometrial cells (n = 705) with no endometrial sampling (n = 1992) studying the reproductive performance of healthy Holstein cows. The selection criteria included primiparous and multiparous cows within 40–60 d postpartum, not inseminated without vaginal discharge or systemic illness. The reproductive performance was assessed during a 210-day period after endometrial sampling. The mean interval from sampling to first service was 19.4 days. In primiparous cows, the PR to first service was lower in sampled cows compared to cows which were not sampled (31.2% vs. 36.5% OR for pregnancy = 1.03; 95% C.I. 0.80–1.33; p = 0.82), whereas in multiparous cows, PR was similar in both groups (29.1% and 28.1% sampled and non-sampled cows, respectively).

In a randomized controlled study, Thome et al. [30][16] evaluated the effect of collecting endometrial cells by UL in postpartum Nellore cows (50–70 days postpartum). In 35 cows, the UL was performed 4 h after timed artificial insemination, while 93 were not sampled. No significant differences in PR were found between sampled and non-sampled groups (54.2% vs. 56.7%, respectively, p > 0.05).

2.2. Cytobrush Studies

In a prospective cohort study, Kaufman et al. [19][17] evaluated the effect of CB sampling the endometrium 4 h after artificial insemination on pregnancy rate to first service in cows calved at least 65 days. PR was similar for sampled and non-sampled cows (43.3% vs. 41.7%, p > 0.05), although significantly higher in primiparous than multiparous cows (54.3 vs. 38.5%, p < 0.05).

2.3. Endometrial Biopsy Studies

In a case-control study, Goshen et al. [31][18] randomly selected 54 Holstein cows calved approximately 67 days to undergo EB; 157 control cows were paired with sampled cows. The effect of the biopsy on PR to first artificial insemination was calculated using binary logistic regression. The interval from biopsy to first AI was 40.5 days (range 5–111 days). The PR and days from calving to conception in biopsied cows (44.4%; 147.3 days) did not differ significantly from those in control cows (38.9%, 150.8 days).

Etherington et al. [29][19] conducted a randomized controlled trial on 130 postpartum dairy cows and evaluated the effect of postpartum EB between days 26 and 40 postpartum on PR to first AI and calving to conception interval. EB increased the interval from calving to first service (89 days biopsied cows versus 81.5 days for control cows; p = 0.07). However, the PR to first AI for biopsied cows (n = 92; 37%) was not significantly different from non-biopsied cows (n = 69; 39%).

4. Conclusions

Perturbations caused after endometrial sampling might induce acute changes in the endometrial environment, but the ability to support embryo development and maintain a pregnancy is recovered. As an indirect indicator of uterine response to artificial insemination [71][20], changes in uterine blood flow have been measured using color Doppler transrectal ultrasonography. An increase in uterine blood flow was observed within 4 h of the procedure, which returned to baseline by 24 h, indicating that these procedures may induce a short acute inflammatory response. Although previous reports indicate that performing UL induces endometrial irritation caused either by the fluid [72][21] or by the device [73][22], studies in mares [74,75][23][24] and women [76][25] have demonstrated that UL did not induce significant morphological changes to the endometrial tissue [77][26]. Just before artificial insemination, Pascottini et al. collected endometrial cells using CT in nulliparous heifers [59][27] and multiparous cows [60][28], and then observed pregnancy rates of 62% and 43%, respectively, which are similar to pregnancy rates reported in non-sampled dairy cows [78][29]. Similarly, Cheong et al. [18][11] and Thome et al. [30][16] performed UL 4 h after insemination without affecting pregnancy rates which is consistent with results in other species such as horses where fertility is not reduced by post-breeding UL [79][30]. In ET studies, CB sampling one cycle before transfer (74) or collecting UL on day 1 postoestrus during the ongoing cycle [28][31] did not affect the pregnancy rates after ET. Therefore, it seems likely that recovering endometrial fluid or cells did not adversely affect fertilization and early embryo development but the time of sampling should be considered to allow the endometrial environment to recover after it is disturbed so as to not affect pregnancy outcome.

References

- Sheldon, I.M.; Lewis, G.S.; LeBlanc, S.; Gilbert, R.O. Defining postpartum uterine disease in cattle. Theriogenology 2006, 65, 1516–1530.

- Lopez-Helguera, I.; Lopez-Gatius, F.; Garcia-Ispierto, I. The influence of genital tract status in postpartum period on the subsequent reproductive performance in high producing dairy cows. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 1334–1342.

- Pascottini, O.B.; Hostens, M.; Dini, P.; Vandepitte, J.; Ducatelle, R.; Opsomer, G. Comparison between cytology and histopathology to evaluate subclinical endometritis in dairy cows. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 1550–1556.

- Kasimanickam, R.; Duffield, T.F.; Foster, R.A.; Gartley, C.J.; Leslie, K.E.; Walton, J.S.; Johnson, W.H. Endometrial cytology and ultrasonography for the detection of subclinical endometritis in postpartum dairy cows. Theriogenology 2004, 62, 9–23.

- Pascottini, O.B.; Dini, P.; Hostens, M.; Ducatelle, R.; Opsomer, G. A novel cytologic sampling technique to diagnose subclinical endometritis and comparison of staining methods for endometrial cytology samples in dairy cows. Theriogenology 2015, 84, 1438–1446.

- Bonnett, B.N.; Miller, R.B.; Martin, S.W.; Etherington, W.G.; Buckrell, B.C. Endometrial biopsy in Holstein-Friesian dairy cows. II. Correlations between histological criteria. Can. J. Vet. Res. 1991, 55, 162–167.

- Chapwanya, A.; Meade, K.G.; Narciandi, F.; Stanley, P.; Mee, J.F.; Doherty, M.L.; Callanan, J.J.; O’Farrelly, C. Endometrial biopsy: A valuable clinical and research tool in bovine reproduction. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 988–994.

- Beltman, M.E.; Mullen, M.P.; Elia, G.; Hilliard, M.; Diskin, M.G.; Evans, A.C.; Crowe, M.A. Global proteomic characterization of uterine histotroph recovered from beef heifers yielding good quality and degenerate day 7 embryos. Domest. Anim. Endocrinol. 2014, 46, 49–57.

- Fischer, C.; Drillich, M.; Odau, S.; Heuwieser, W.; Einspanier, R.; Gabler, C. Selected pro-inflammatory factor transcripts in bovine endometrial epithelial cells are regulated during the oestrous cycle and elevated in case of subclinical or clinical endometritis. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 2010, 22, 818–829.

- Barlund, C.S.; Carruthers, T.D.; Waldner, C.L.; Palmer, C.W. A comparison of diagnostic techniques for postpartum endometritis in dairy cattle. Theriogenology 2008, 69, 714–723.

- Cheong, S.H.; Nydam, D.V.; Galvao, K.N.; Crosier, B.M.; Gilbert, R.O. Effects of diagnostic low-volume uterine lavage shortly before first service on reproductive performance, culling and milk production. Theriogenology 2012, 77, 1217–1222.

- Ramirez-Garzon, O.; Satake, N.; Lyons, R.E.; Hill, J.; Holland, M.K.; McGowan, M. Endometrial biopsy in Bos indicus beef heifers. Reprod. Domest. Anim. 2017, 52, 526–528.

- Helfrich, A.L.; Reichenbach, H.-D.; Meyerholz, M.M.; Schoon, H.-A.; Arnold, G.J.; Fröhlich, T.; Weber, F.; Zerbe, H. Novel sampling procedure to characterize bovine subclinical endometritis by uterine secretions and tissue. Theriogenology 2020, 141, 186–196.

- Watson, E.D.; Sertich, P.L. Effect of repeated collection of multiple endometrial biopsy specimens on subsequent pregnancy in mares. J. Am. Vet. Med. Assoc. 1992, 201, 438–440.

- Sar-Shalom Nahshon, C.; Sagi-Dain, L.; Wiener-Megnazi, Z.; Dirnfeld, M. The impact of intentional endometrial injury on reproductive outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 2018, 25, 95–113.

- Thome, H.E.; de Arruda, R.P.; de Oliveira, B.M.; Maturana Filho, M.; de Oliveira, G.C.; Guimaraes Cde, F.; de Carvalho Balieiro, J.C.; Azedo, M.R.; Pogliani, F.C.; Celeghini, E.C. Uterine lavage is efficient to recover endometrial cytology sample and does not interfere with fertility rate after artificial insemination in cows. Theriogenology 2016, 85, 1549–1554.

- Bicalho, M.L.S.; Machado, V.S.; Higgins, C.H.; Lima, F.S.; Bicalho, R.C. Genetic and functional analysis of the bovine uterine microbiota. Part I: Metritis versus healthy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 3850–3862.

- Goshen, T.; Galon, N.; Arazi, A.; Shpigel, N. The effect of uterine biopsy on reproductive performance of dairy cattle: A case control study. Isr. J. Vet. Med. 2012, 67, 34–38.

- Etherington, W.G.; Martin, S.W.; Bonnett, B.; Johnson, W.H.; Miller, R.B.; Savage, N.C.; Walton, J.S.; Montgomery, M.E. Reproductive performance of dairy cows following treatment with cloprostenol 26 and/or 40 days postpartum: A field trial. Theriogenology 1988, 29, 565–575.

- Oliveira, B.M.; Arruda, R.P.; Thome, H.E.; Maturana Filho, M.; Oliveira, G.; Guimaraes, C.; Nichi, M.; Silva, L.A.; Celeghini, E.C. Fertility and uterine hemodynamic in cows after artificial insemination with semen assessed by fluorescent probes. Theriogenology 2014, 82, 767–772.

- Brook, D. Uterine cytology. In Equine Reproduction; Lea & Febiger: Malvern, PA, USA, 1993; pp. 246–254.

- Kasimanickam, R.; Duffield, T.F.; Foster, R.A.; Gartley, C.J.; Leslie, K.E.; Walton, J.S.; Johnson, W.H. A comparison of the cytobrush and uterine lavage techniques to evaluate endometrial cytology in clinically normal postpartum dairy cows. Can. Vet. J. 2005, 46, 255–259.

- Linton, J.K.; Sertich, P.L. The impact of low-volume uterine lavage on endometrial biopsy classification. Theriogenology 2016, 86, 1004–1007.

- Ball, B.A.; Shin, S.J.; Patten, V.H.; Lein, D.H.; Woods, G.L. Use of a low-volume uterine flush for microbiologic and cytologic examination of the mare’s endometrium. Theriogenology 1988, 29, 1269–1283.

- Hannan, N.J.; Nie, G.; Rainzcuk, A.; Rombauts, L.J.; Salamonsen, L.A. Uterine lavage or aspirate: Which view of the intrauterine environment? Reprod. Sci. 2012, 19, 1125–1132.

- Koblischke, P.; Kindahl, H.; Budik, S.; Aurich, J.; Palm, F.; Walter, I.; Kolodziejek, J.; Nowotny, N.; Hoppen, H.O.; Aurich, C. Embryo transfer induces a subclinical endometritis in recipient mares which can be prevented by treatment with non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs. Theriogenology 2008, 70, 1147–1158.

- Pascottini, O.B.; Hostens, M.; Dini, P.; Van Eetvelde, M.; Vercauteren, P.; Opsomer, G. Prevalence of cytological endometritis and effect on pregnancy outcomes at the time of insemination in nulliparous dairy heifers. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 9051–9056.

- Pascottini, O.B.; Hostens, M.; Sys, P.; Vercauteren, P.; Opsomer, G. Cytological endometritis at artificial insemination in dairy cows: Prevalence and effect on pregnancy outcome. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 588–597.

- Macmillan, K.; Loree, K.; Mapletoft, R.J.; Colazo, M.G. Short communication: Optimization of a timed artificial insemination program for reproductive management of heifers in Canadian dairy herds. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 4134–4138.

- Brinsko, S.P.; Varner, D.D.; Blanchard, T.L. The effect of uterine lavage performed four hours post insemination on pregnancy rate in mares. Theriogenology 1991, 35, 1111–1119.

- Martins, T.; Pugliesi, G.; Sponchiado, M.; Gonella-Diaza, A.M.; Ojeda-Rojas, O.A.; Rodriguez, F.D.; Ramos, R.S.; Basso, A.C.; Binelli, M. Perturbations in the uterine luminal fluid composition are detrimental to pregnancy establishment in cattle. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 9, 70.