Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a pivotal role in biological processes and continuous ROS production in normal cells is controlled by the appropriate regulation between the silver lining of low and high ROS concentration mediated effects. Interestingly, ROS also dynamically influences the tumor microenvironment and is known to initiate cancer angiogenesis, metastasis, and survival at different concentrations. At moderate concentration, ROS activates the cancer cell survival signaling cascade involving mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1/2 (MAPK/ERK1/2), p38, c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), and phosphoinositide-3-kinase/ protein kinase B (PI3K/Akt), which in turn activate the nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB), matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). At high concentrations, ROS can cause cancer cell apoptosis. Hence, it critically depends upon the ROS levels, to either augment tumorigenesis or lead to apoptosis.

1. Introduction

Despite continuous efforts in the development of novel treatment modalities, cancer still remains one of the most dreadful diseases in both developed and, developing countries; being an indomitable conundrum for scientists worldwide. Based on the recently published GLOBOCAN 2018 report, there was a prediction of 18.1 million new cancer cases and 9.6 million cases with cancer mortality in women and men. If the industrial development accompanied by environmental pollution and alterations in the human lifestyle, continue as fast as hitherto, predictions suggest by 2030, almost 13 million people will die from different cancers each year

[1]. This would be a huge burden to the whole society and needs urgent intervention at different levels, including not only scientific contribution but also political statutes in implementation of diverse preventive measures.

The complexity of cancer is attributed to its multifaceted and multifactorial presentation. In the past few decades, the disruption of redox balance has been illustrated to be one of the most important reasons underlying cancer development, its progression, and metastasis in human cells

[2]. This disproportionality in redox homeostasis is documented to be induced via increased free radicals, predominantly ROS. These highly active radicals originate from both intrinsic and extrinsic sources. Intrinsic sources of ROS mostly include mitochondria, inflammatory cells, and several enzymatic cellular complexes; extrinsic sources of ROS include pro-oxidant environmental toxins, radiation,

[3] and diverse chemical compounds, including alcohol, tobacco smoking, and certain drugs

[4]. Such free radicals can cause damage to various important biomolecules, including lipids, proteins, and nucleic acids, leading to oxidative stress and damaging different human tissues.

Elevated ROS levels, accompanied with down-regulation of cellular antioxidant enzyme systems, result in malignant transformation via different molecular targets, such as NF-κB and nuclear factor (erythroid-derived 2)-like-2 factor (Nrf2)

[5][6][5,6]. Signaling cascades regulated by these key factors generate an inflammatory environment leading to the suppression of apoptotic cell death, tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastasis; which cumulatively augment initiation, development, and progression of malignant neoplasms (

Table 1). This review article summarizes the present up-to-date knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of ROS generation, its role in tumor growth and metastasis, along with highlighting the potential targets of the ROS cascade for potential therapeutic strategies.

Table 1. Role of ROS in cancer progression.

| Effect |

Mechanism |

Cell Line |

References |

| Oxidative Stress |

Aquaporin AQP5-mediated H2O2 influx rate indicates the presence of a highly efficient peroxiporin activity and consequently activates signaling networks related to cell survival and cancer progression |

Pancreatic Carcinoma line-3 (BxPC3) |

[7] |

| |

PCB118 promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell (HCC) proliferation via Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2)-dependent up-regulation of glycolysis, which is mediated by Aryl hydrocarbon receptor/Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate oxidase (AhR/NADPH oxidase)-induced ROS prouction |

SMMC-7721 |

[8] |

| |

Enhanced ROS of exposed cells alters the mitochondrial metabolic activities in terms of increased mitochondrial mass and DNA content and initiates cancer progression through modifying cellar biomarkers |

MOE1A |

[9] |

| Inflammatory markers |

Serum ROS and damaged mtDNA may be markers of mitochondrial metabolism through oxygenation of the primary tumor and results in systemic inflammation and adverse outcomes of locally advanced rectal cancer (LARC) |

HCT-116, HT-29, and LoVo |

[10] |

| |

Inflammation in the stroma induces TNF-α signaling and the NOX1/ROS signaling pathway is activated downstream with expression of TLR2 which is an important tumor-promoting mechanism stimulated by inflammation |

Mouse Model |

[11] |

| |

Alkylating agents may evoke inflammatory responses that seem to contribute to malignant progression in specific breast cancer cells |

MDA-MB231, Hs578T, SKBR3 and MCF7 |

[12] |

| Metastasis |

ROS induce epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), the glycolytic switch, and mitochondrial repression by activating the Distal-less homeobox-2 (Dlx-2)/Snail axis, thereby playing crucial roles in metastasis |

MCF-7 |

[13] |

| |

Elevated mitochondrial ROS via fatty acid β-oxidation, activates the MAPK cascades, results in EMT process of ROS high tumor spheres (RH-TS) cells, and enhances metastasis |

4 T1, SW480, HCT116 and HT29 |

[14] |

| |

Loss of TMEM126A induces ROS production with mitochondrial dysfunction and subsequently metastasis by activating extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and EMT |

MDA-MB-231HM |

[15] |

| |

PM2.5 exposure induces ROS, which activates loc146880 expression and promotes the malignant behavior |

A549 |

[16] |

| Angiogenesis |

ROS-ERK1/2-HIF-1α-VEGF-induces angiogenesis by increased level of RRM2 |

C33A and MCF-7 |

[17] |

| |

High glucose increases angiogenesis and decreases apoptosis due to activation of the NF-κB pathway by increasing ROS |

MCF-7 |

[18] |

| |

27-Hydroxycholesterol (27HC) enhanced the generation of ROS and activates the STAT-3/VEGF signaling in an ER independent manner which results in induced angiogenesis |

Breast Cancer Cells |

[19] |

2. Role of ROS in Cancer Progression

2.1. ROS-Mediated Induction of Oxidative Stress

Oxygen is a multifaceted molecule, which is crucial for life sustainability but can be harmful when it is converted to ROS through oxidation-reduction reactions. The distinct aspect of ROS was first identified by Gerschmann in 1954

[20][21][20,21] and its free radical potential was described by Denham Harman in the free radical theory of aging in 1956

[21][22][21,22]. This initial work from the group; steadily triggered further investigations in the dimension of ROS to decipher their precise role in biological systems

[21]. The discovery of the first described antioxidant enzyme, superoxide dismutase (SOD), by McCord

[21][23][21,23] postulated the instrumental role of ROS through free radical generation. Following the initial studies on the substantial potential role of ROS, the focus shifted to delineate the beneficial and harmful effects of ROS in numerous pathological and physiological processes and their mechanism of action.

In a normal cell, ROS levels are balanced through numerous detoxification processes regulated through antioxidant enzymes. Hence, ROS homeostasis is well sustained, which contributes to the maintenance of redox balance in healthy cells. The complex I and III of the mitochondrial respiratory chain under high membrane potential, are contemplated to be the point of origin of ROS particularly, but numerous other resources may also play a pivotal role in elevated ROS generations, such as α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase, monoamine oxidase, mitochondrial p66

Shc, sirtuins, Nrf2, and forkhead box O3 (FOXO3) besides the underlying redox cycling reactions

[24]. This elevated ROS production or defective defense mechanism may also lead to elevated oxidative stress levels leading to diverse pathological conditions. Examples of endogenous sources of ROS include mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation, p450 metabolism, peroxisomes, and from the activation of inflammatory cells such as macrophages and neutrophils. It is thought that during the mitochondrial respiratory process, 1–2% of molecular oxygen is converted to ROS through one to three electron reductions and this leads to the formation of hydroxyl, hydrogen peroxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite radicals

[25].

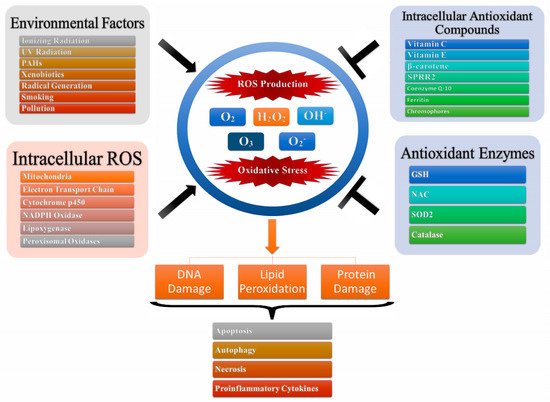

Oxidative stress is one of the main leading causes of toxicity which is attributed to the interactions of ROS as well as reactive nitrogen species (RNS) with cellular macromolecules such as DNA, lipid, and proteins, which interfere with the signal transduction pathways such as protein kinases, phosphatases, and transduction mechanisms (

Figure 1). The pathological consequences of oxidative stress are characterized by impaired glucose tolerance due to mitochondrial oxidative stress. This is attributed to pro-oxidants changing their thiol/disulphide redox state which leads to diabetes mellitus and cancer or through the augmented action of either NAD(P)H oxidase leading to inflammatory oxidative conditions which is associated with chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis or through the action of xanthine oxidase-induced ROS formation which has been associated with reperfusion injury and ischemia

[21]. Further, the ageing process can be attributed to the detrimental magnitude of free radicals leading to DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, and protein oxidation

[21][22][21,22].

Figure 1. Oxidative stress and production of reactive oxygen species. Intracellular ROS and environmental factors (exogenous ROS) initiates ROS production leading to oxidative stress which in turn leads to DNA/lipid/protein degradation resulting in apoptosis, autophagy, necrosis and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

The connotation of oxidative and nitrosative stress with chronic and acute disease presentation is based on the biomarkers validated for oxidative stress. In an excellent review by Dalle-Donne and coworkers

[21][26][21,26], the group summarized the biomarkers of oxidative stress and their correlation with human disease presentation. Natural antioxidants can protect the cell via scavenging the ROS. They may be separated into three classes—endogenous antioxidants (bilirubin, catalase (CAT), ferritin, SOD, glutathione, coenzyme Q, l-carnitine, alpha lipoic acid, glutathione peroxidase (GPx), melatonin, metallothionein, thioredoxins, peroxiredoxins, and uric acid), natural antioxidants (ascorbic acid, polyphenol metabolites, β-carotene, vitamin E, and vitamin A), and synthetic antioxidants (Nrf2, tiron, pyruvate, selenium, and

N-acetyl cysteine (NAC)). Protecting the organism against harmful oxidants is a complex interaction between these antioxidants. High intracellular ROS concentration is important for damage, but another important fact is the equilibrium between ROS and antioxidant systems. The ROS production/antioxidant defense system balance is required for homeostasis

[25]. Under normal conditions antioxidants outbalance oxidants but under oxidative conditions pro-oxidants prevail antioxidants

[27].

2.2. Inflammatory Markers and ROS

The intricate relationship between cancer and, prolonged inflammation has been thoroughly investigated since Virchow’s hypothesis

[28]. In 1863, Rudolf Virchow propounded that the “lymphoreticular infiltrate” reflected the origin of cancer at the locations of chronic inflammation

[29]. The obtained epidemiological and experimental data from the numerous studies supported Virchow’s hypothesis and revealed that inflammatory processes regulate the course of cancer based on the level of inflammation-related factors, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines, in the tumor microenvironment, either by producing an antitumor response or by inducing cell transformation and malignancy

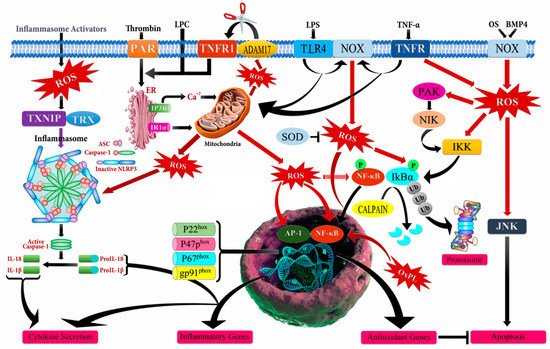

[30][31][32][30,31,32]. One of the major regulatory components in the relationship between cancer and chronic inflammation is ROS that has an ability to affect the type, presence, and levels of inflammation-modulating factors such as activator protein 1 (AP-1), β-catenin/Wnt (wingless related integration site), HIF-1α (hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha), NF-κB, PPAR-γ (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma), p53, inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors

[27][33][34][35][27,33,34,35]. However, it should be noted that there is a complex crosstalk between chronic inflammation, ROS accumulation, and cancer progression (

Figure 2). The inflammatory cells in the tumor microenvironment lead to a massive production of ROS by activating the oxidant-generating enzymes such as inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), myeloperoxidase (MPO), NADPH oxidase, and xanthine oxidase (XO), and by up-regulating cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) and lipoxygenase (LOX) to remove and disrupt the biological, chemical, and physical factors. The abundant accumulation of ROS also produces oxidative damage to the DNA, RNA, proteins, lipids, and mitochondria.

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of mechanism of action of reactive oxygen species (ROS) leading to inflammation. ADAM17 (ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17); ASC (Activating signal co-integrator 1); BMP4 (Bone morphogenetic protein 4); IKB-α (Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa B kinase regulatory subunit alpha); IKK (Inhibitor of nuclear factor kappa-B kinase); IP3R (Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 3); JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase); LPC (Lysophosphatidylcholine); LPS (Lipopolysaccharide); NF-кB (Nuclear factor kappa subunit B); NLRP3 (NLR family pyrin domain containing 3); NOX (NADPH oxidase); OxPL (Oxidized phospholipids); PAR (Par family cell polarity regulator); PAK (p21 (RAC1) activated kinase); SOD (Superoxide dismutase); TLR4 (Toll like receptor 4); TNF-α (Tumor necrosis factor alpha); TNFR (TNF receptor superfamily); TNFR1 (TNF receptor superfamily 1); TXNIP (Thioredoxin interacting protein); Ub (Ubiquitin).

This causes an increased mutation load, defects in signal-transduction, inactivation of apoptosis, and overpowered generation of additional ROS that activate the inflammation-modulating factors, inflammatory cytokines, and chemokines

[34][35][36][37][34,35,36,37]. Apart from the induction of chronic inflammation by ROS-mediated NF-κB activation, the active NF-κB is considered to be a key component in the rise of therapy-resistant cancers toward fractional gamma-irradiation therapy and chemotherapeutic agents such as 5-fluorouracil, bortezomib, cisplatin, daunorubicin, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, vinblastine, vincristine, and tamoxifen, through the transcriptional up-regulation of Akt, Bcl-2 (B-cell lymphoma 2), Bcl-xL (B-cell lymphoma- extra-large), cyclin D1, COX-2, survivin, and XIAP (X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis)

[38][39][40][41][42][43][38,39,40,41,42,43]. Targeting ROS consequently seems to be a very promising way to modulate cancer related chronic inflammation and the hallmarks for cancer development such as sustaining proliferative signaling, evading growth suppressors, activating invasion and metastasis, enabling replicative immortality, inducing angiogenesis, and resisting cell death

[37][44][37,44].

2.3. Cancer Metastasis and ROS

Metastasis involves the spread of cancer cells from the primary tumor to the surrounding tissues and to distant organs, and is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality

[45]. Studies reveal that tumor metastasis is not an autonomous program but a complex and multifaceted event, occurring due to the intrinsic mutational burden of cancerous cells and bidirectional interaction between nonmalignant and malignant cells

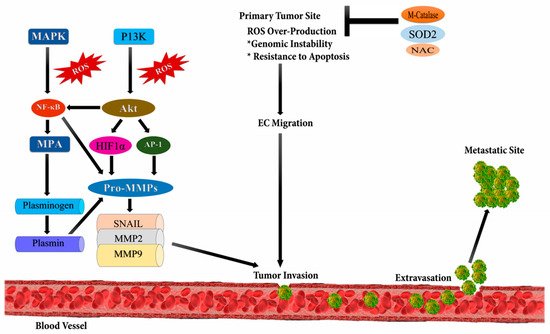

[46]. It occurs due to the up-regulation of several transcriptional factors such as NF-ĸB, ETS-1 (ETS proto-oncogene 1, transcription factor), Twist, Snail, AP-1, and Zeb (zinc finger E-box binding homeobox); metalloproteases viz. MMP-9 and, MMP-2; and chemokines or cytokines like transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) (

Figure 3)

[47]. ROS plays an important role in the migration and invasion of cancerous cells. ROS are mainly produced as byproducts during mitochondrial electron transport in aerobic respiration and have numerous deleterious effects

[48]. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) is the major cause of tumor metastasis, where epithelial cells lose their polarity, cell-cell adhesion, and gain mobility.

Figure 3. Reactive oxygen species and metastasis. High levels of reactive oxygen species leads to metastasis through the stimulation of phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit/AKT serine/threonine kinases/mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (PI3K/Akt/mTOR), and MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinases) signaling pathways which activates downstream SNAIL, MMP2 (metalloproteinase 2), and MMP9 (metalloproteinase 9) enzymes initiating epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) leading to metastasis.

Several studies have proved ROS to be a major cause of EMT. TGF-β1 regulates uPA (Urokinase type Plasminogen Activator) and MMP-9 to facilitate cell migration and invasion through ROS-dependent mechanisms

[49]. Another study revealed that ROS increases tumor migration by inducing hypoxia mediated MMPs and, cathepsin expression

[50][51][50,51]. According to a study reported by Zhang, NADPH oxidase 4 (NOX4)-dependent ROS production is necessary for TGF β1-induced EMT in MDAMB-231C and MCG-10A cell lines

[52]. P53 also plays a major role in cell migration using cytokines TGF β1. Pelicano et al. suggested that mitochondrial dysfunction can lead to increased ROS production, which further up-regulates C-X-C motif chemokine 14 (CXCL14) expression through the AP-1 signaling pathway and, enhances cell mobility by elevating cytosolic Ca

2+ levels

[53]. ROS activate Nrf2 that stimulates Klf9 (Krupple like factor 9), thus activating ERK1/2; and results in an increased ROS production in cancer cells. Thus, a premalignant growth can be suppressed by using topical antioxidants that target Klf9

[54][55][54,55].

Mitochondrial Ca

2+ also plays an important role in cancer metastasis. Jin and his colleagues observed that MCUR1 (Mitochondrial Calcium Uniporter Regulator 1) is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) which promotes EMT by activating ROS/Notch1/Nrf2 pathways. Thus, MCUR1 can be a potential target for the treatment of HCC

[56]. Aydin et al. analyzed that NOX2 generates ROS, which influence metastasis by down-modulating the function of natural killer (NK) cells, and its inhibition can restore the IFNγ (interferon gamma)-dependent NK cell-mediated clearance of myeloma cells

[57]. Vimentin protein also plays a major role in cancer initiation and progression such as EMT, and metastasis. Oxidative stress caused by HIF-1 regulates vimentin gene transcription, which helps in the formation of invadopodia during cancer cell invasion and migration

[58]. Inhibition of vimentin expression by RNAi can reduce cell metastasis and hence decrease tumor volume

[59]. ROS also induces epigenetic changes in the promoter region of E-cadherin and various other tumor suppressor genes, hence leading to tumor progression and metastasis. It causes hyper-methylation of the promoter gene by increasing Snail expression. Snail induces DNA methylation with the help of histone deacetylase 1 (HDAC1) and DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1)

[60].

2.4. Angiogenesis and ROS

During the initial stages of tumorigenesis, new blood vessels are formed from the pre-existing vasculatures, a process known as angiogenesis, which supports tumor proliferation and survival

[61][62][63][64][61,62,63,64]. ROS-dependent angiogenesis is initiated through cancer proliferation, which in turn increases the metabolic rate leading to the generation of high ROS levels

[63][64][63,64]. These elevated ROS levels lead to oxidative stress in the tumor microenvironment, which initiates secretion of angiogenic modulators

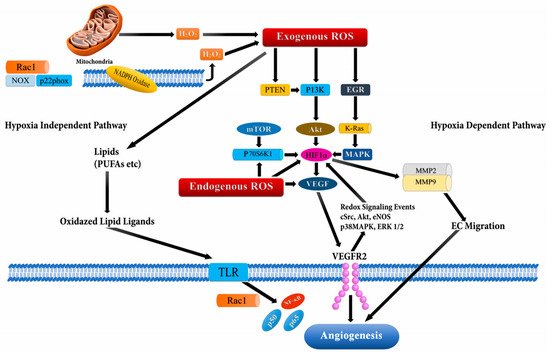

[65]. Both endogenous and exogenous ROS spearheads stimulation of growth factors, cytokines, and transcription factors like VEGF and HiF-1α, which promote tumor migration and proliferation through ROS-dependent cellular signaling

[62][65][66][62,65,66]. The signaling cascade through ROS mediation has been documented to perpetuate VEGF secretion and activate the PI3K/Akt/mammalian target of the rapamycin (mTOR) pathway through hypoxia independent or dependent mechanisms (through stabilization of HIF-1α which increases production of VEGF) (

Figure 4),

[67]. Additionally, the Ras signaling pathway has also been reported to up-regulate VEGF secretion

[68]. Recently, mutant p53 was also recognized to modulate the angiogenic response in tumor proliferation through the ROS-mediated activation of VEGF-A and HiF-1 in HCT116 human colon carcinoma cells

[69]. The mechanism of ROS-mediated angiogenesis has been extensively studied to understand the signaling cascade modulating cancer progression. In a study carried out using MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, deferoxamine (DFO) induced HIF-1α through ERK1/2 phosphorylation which promoted tumor migration and metastasis

[70].

Figure 4. Angiogenesis activation through reactive oxygen species (ROS) via hypoxia dependent and hypoxia independent pathways. The hypoxia dependent pathway increases vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) expression via the phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulatory subunit/AKT serine/threonine kinases/mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (PI3K/Akt/mTOR), PTEN (phosphatase and tensin homolog), and MAPK (Mitogen-activated protein kinases) signaling cascades via HIF-1α (Hypoxia-inducible factor1-alpha) and p70S6K1 (ribosomal protein S6 kinase B1), which release various cytokines, growth factors, and up-regulation of MMPs (matrix metalloproteinases) leading to angiogenesis. The hypoxia independent pathway leads to angiogenesis through oxidative lipid ligands which activates NF-кB (Nuclear factor kappa subunit B) via Toll-like receptors (TLRs).

Han and colleagues demonstrated that the elevated levels of epidermal growth factor (EGF) triggered hydrogen peroxide production, which stimulated p70S6K1 via the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway, leading to the activation of downstream VEGF and HiF-1α

[71]. On similar lines, Liu et al. reported that EGF lead to increased production of hydrogen peroxide in OVCAR-3 ovarian cancer cells, which activated the AKT/p70S6K1 pathway, thereby resulting in increased VEGF expression

[72]. The group further documented that catalase overexpression and rapamycin inhibited angiogenesis. Hydrogen peroxide was also illustrated to inactivate phosphatase and tension homolog (PTEN) through the reversible oxidation of phosphatases in the cysteine thiol group and promote activation of the PI3K/Akt/mTORsignaling cascade and Ras

[73].

In another study on ovarian cancer cells, Xia and colleagues documented that NOX4 knockdown lead to a reduction of VEGF and HIF-1α, which in turn regulated tumor angiogenesis

[74][75][74,75]. A similar mechanism of action of ROS was illustrated through experiments in WM35 melanoma cells, where Akt induced the expression of NOX4

[75][76][75,76]. NADPH oxidase 2 (Nox2)-derived ROS was also reported to induce cancer progression and migration, modulated through the ERK/PI3K/AKT/Src (Proto-oncogene tyrosine -protein kinase)-dependent pathway leading to the activation of endothelial cells and induction of angiogenesis

[77][78][79][77,78,79]. Nox1 (NADPH oxidase 1) was also reported to mediate the Ras-dependent up-regulation of VEGF expression and, angiogenesis via the Ras/ERK-dependent Sp1 phosphorylation and activation in CaCO-2 colon cancer cells

[80][81][80,81]. In human umbilical vein endothelial cell (HUVECs), Angiopoietin -1 (Ang1) induced transient ROS through the activation of endothelial specific tyrosine kinase receptor, Tie-2, and p44/42, MAPK leading to vascular remodeling

[82].

Moreover, copper was reported to increase the ROS-mediated expression of VEGF, HiF-1α, and G-protein estrogen receptor (GPER) in HepG2 hepatocellular carcinoma cells and SkBr3 breast cancer cells via activation of the EGFR/ERK/c-Fos pathway

[83][84][83,84]. Similarly, the cadmium activated ERK/Akt pathway induced ROS expression and HiF-1; its downstream pro-angiogenic molecule in BEAS-2B bronchial epithelial cells

[85]. In addition, several other extracellular remodeling proteins and transcription factors (p53, HiF-1α, VEGF, and MMPs) have been documented to be regulated by ROS

[86][87][88][89][90][91][86,87,88,89,90,91]. Also, numerous studies in cancer cell lines (MCF-7, HepG2, H-1299, PC-3) showed that ROS acted through the PI3K/Akt signaling cascade, thereby enhancing HiF-1α expression and angiogenesis

[92][93][94][92,93,94]. In view of literature supporting the angiogenic potential of ROS, therapeutic targets with antioxidant potential and targeting subsequent signaling cascades will be of clinical significance in the management and treatment of patients through down-regulation of neovascularization. Different strategies to restore redox imbalance is another avenue to improve outcome of diseases. As the interventional trials with small anti-oxidants have not been effective, further research to explore disease-specific ROS may be of clinical relevance for futuristic drug development.