Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Craig Robbins and Version 2 by Rita Xu.

Blount’s disease is an idiopathic developmental abnormality affecting the medial proximal tibia physis resulting in a multi-planar deformity with pronounced tibia varus. A single cause is unknown, and it is currently thought to result from a multifactorial combination of hereditary, mechanical, and developmental factors.

- Blount’s disease

- infantile

- early-onset

- late-onset

- juvenile

- adolescent

- tibia vara

1. Introduction

Blount’s disease is eponymous with non-physiologic tibia vara in skeletally immature patients. It is an idiopathic developmental abnormality affecting the medial proximal tibia growth plate, resulting in a multiplanar deformity with pronounced tibia varus [1][2][1,2]. The first clinical and radiographic description of a single patient was by Erlacher in the German literature in 1922 [3]. In 1937, Blount provided detailed histologic and radiographic descriptions of 13 original cases of tibia vara in the English literature [4]. He coined the term “osteochondrosis deformans tibiae” and characterized the early-onset form (herein referred to as infantile tibia vara (ITV)) that is clinically apparent before age four and the late-onset form (herein referred to as late onset tibia vara (LOTV)) that develops in older children prior to skeletal maturity [5]. In 1990, Thompson and Carter re-classified Blount’s disease into three age-onset groups: (1) infantile: through three years of age, (2) juvenile: four to ten years of age, and (3) adolescent: 11 years or older before skeletal maturity [6]. The juvenile form is the least common and exists with characteristics of the infantile and late-onset forms. This discussion will utilize ITV and LOTV as the main categories of Blount’s disease.

ITV is often bilateral, is more likely in females, and has more severe tibial deformity than LOTV [7] (Figure 1). LOTV is more often unilateral and more often has additional femoral deformities [8]. Both are more prevalent in Blacks, Hispanics, and Scandinavians than other populations and nationalities, especially LOTV [9][10][9,10]. The tibia vara is the predominant feature in limbs affected by Blount’s disease and, if left untreated, progresses to knee deformity, gait abnormalities, and premature medial compartment knee arthritis [11][12][13][11,12,13].

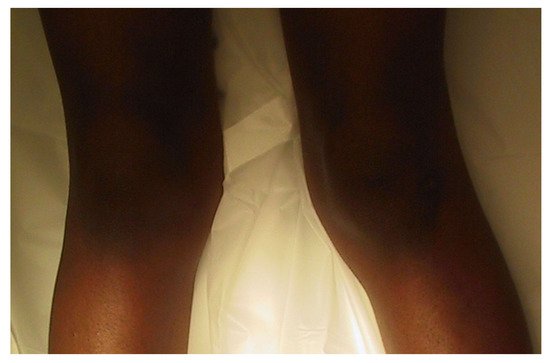

Figure 1.

A 20-month-old child with ITV.

2. Etiology and Pathophysiology

A single cause for Blount’s disease is unknown, and it is currently thought to result from a multifactorial combination of genetic, humoral, biomechanical, and developmental factors [14][15][16][17][14,15,16,17]. Early walking and obesity suggest a mechanical contribution to deformity in ITV [18]. LOTV is also linked with obesity [6][19][6,19]. A relationship with vitamin D deficiency exists in all types [19][20][21][22][23][19,20,21,22,23]. Wenger et al. proposed that age-related differences in osseous physiology lead to the clinically and radiologically distinct entities of early- and late-onset disease [24]. In young children, the tibial ossification center is cartilaginous and pliable; in adolescence, however, the tibial epiphysis is well-formed and bony and does not deform. Repetitive compressive forces across the medial knee in a predisposed young child with physiologic varus leads to a vicious cycle of growth inhibition with worsening varus, delayed ossification, and deformity with characteristic sloping of the medial epiphysis [24]. Wenger et al. postulated that most cases of LOTV occur in children with mild residual physiologic genu varus. With the adolescent growth spurt and rapid weight gain, the borderline varus suddenly worsens due to a similar mechanism of pressure-induced growth-inhibition of the medial physis [24].

Regardless of the etiology, the clinical and radiographic findings are consistent with each type of Blount’s disease, and the severity of deformities relates to the age of onset and therefore the duration and amount of growth suppression of the medial proximal tibia physis. ITV is characterized by more severe deformity of the proximal tibia with medial plateau depression. Despite the medial growth disturbance, the lateral tibial physis and fibula grow normally. Because the fibula is slightly inclined in the sagittal plane (more posterior proximal and more anterior distal), relative overgrowth creates a crank-shaft phenomenon resulting in internal tibial torsion [5]. Schoeneker et al. reported a significant distal femoral valgus in four of seven children with advanced ITV [25]. Because they begin at a later age, the deformities in LOTV are often less pronounced, and there is not the medial tibial plateau depression seen with ITV (Figure 2). Distal femoral varus is common, and Sabharwal reported that it contributes up to one third of the total varus deformity in LOTV [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Increased femoral anteversion has been reported as well [28]. As the knee deformities progress in both types, significant strain is put on the lateral collateral ligament, which can lead to laxity, joint line divergence, and knee instability [29]. The pathologic changes in Blount’s disease progress over time to develop complex multiplanar deformities often with additional deformities in the same limb.

Figure 2.

A 14-year-old with left-sided LOTV.

3. ITV Differential Diagnosis and Clinical Features

Bow-leg deformity in infants and children is common. The differential diagnosis includes metabolic conditions such as Rickets and renal osteodystrophy, congenital deformity such as tibial hemimelia, genetic conditions such as bone dysplasias, post-infectious and post-traumatic etiologies, physiologic bowing, and ITV [30]. A comprehensive history and thorough physical exam limit the differential list; genetic and metabolic abnormalities often involve additional organ systems and can affect the entire skeletal system, and the history suggests acquired causes for deformity. The clinical exam should include strength, rotational profile, joint range of motion, joint stability, neuromuscular function, limb length measurement, gait pattern, and spine alignment.

Physiologic bowing and ITV are often difficult to distinguish from each other. The combination of hip flexion and external rotation with increased internal tibial torsion worsen the appearance of genu varus with knee flexion in children with physiologic bowing. The salient clinical features in ITV are a painless varus deformity of the knee with internal tibial torsion. In unilateral cases there is a leg length discrepancy. There is a characteristic lateral thrust with gait, and knee stability testing may show lateral ligamentous laxity [15]. Often there is a palpable prominence on the medial proximal tibia metaphysis corresponding with the site of pathology. In general, ITV has a more abrupt deformity centered on the proximal tibia, whereas physiologic bowing shows a gentler curve affecting the entire leg below the knee.

The Cover Up test described by Davids et al. is an accurate clinical screening tool to differentiate between physiologic bowing and ITV [31]. It is a qualitative test comparing the clinical alignment of the distal thigh to the top portion of the leg with the child supine and the legs rotated so the patellae are forward. The middle portions of the thighs and legs are covered up so only the knee is visible. Neutral or varus alignment at the lateral knee is considered a positive test (Figure 3) and suggests the possibility of ITV. Obvious valgus appearance at the lateral knee is considered negative (Figure 4) and indicates physiologic bowing. In their study, all patients with radiographic ITV had a positive test (sensitivity = 1.00), and 18 of 25 children with a positive test had or developed ITV (positive predictive value = 0.72). A total of 43 of 50 children with physiologic bowing had a negative test (specificity = 0.86), and all children with a negative test had physiologic bowing (negative predictive value = 1.00). Radiographic evaluation and routine follow-up are warranted in any child with a positive test or suspicion of ITV.

Figure 3. Positive Cover Up test of the child in Figure 1 demonstrating neutral or varus alignment at the lateral knee indicative of ITV.

Figure 4. Negative Cover Up test demonstrating valgus alignment at the lateral knee indicative of physiologic genu varus.