Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic disorder characterized by widespread and persistent musculoskeletal pain, which is usually associated with other symptoms such as fatigue, tiredness, insomnia, stiffness, cognitive deficits, and emotional comorbidities (i.e., depression and anxiety). FMS patients usually display a high rate of psychiatric disorders compared to the general population. FMS has been also associated with higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect. High levels of stress, pain catastrophizing, and angry rumination have been also reported in FMS patients. Additionally, there are a tendency to internalize and suppress anger in FMS patients. Regarding personality in FMS, some studies have observed some FMS features (e.g., high impulsivity, harm avoidance, self-transcendence and neuroticism, and low conscientiousness, cooperativeness and self-directedness), while other authors had not found any particular personality trait. Some personality disorders (i.e., obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, borderline personality, avoidant personality disorder, and histrionic personality disorder) seem to be more frequent in FMS patients than in general population. Moreover, previous research has reported a greater presence of the type D personality and high levels of alexithymia in a significant proportion of FMS patients. It is necessary to improve the understanding of the role of affect and personality in the clinical practice with chronic pain patients, in order to improve the success of a personalized oriented treatment and increase their health-related quality of life.

- fibromyalgia

- pain

- affect

- personality

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia syndrome (FMS) is a chronic disorder characterized by widespread and insistent musculoskeletal pain.[1] Its prevalence in the general population has been estimated around 2 to 4%.[1] FMS has been traditionally considered more predominant in women than men (between 61 to 90%), although recent studies suggested that this disproportion may result from biases studies.[2][3] With respect to FMS pathophysiology, it remains unknown. One of the most accepted hypothesis is the presence of central sensitization to pain and impairments in endogenous pain inhibitory mechanisms.[4][5]

FMS is usually associated to other symptoms such as fatigue, tiredness, insomnia, stiffness, cognitive deficits (often called ‘‘fibro fog’’)[6] and emotional comorbidities (i.e., depression and anxiety). In addition, the new FMS diagnostic criteria of 2010 have also proposed other possible accompanying symptoms, for instance: irritable bowel syndrome, painful and frequent urination, constipation, neck pain, skin rash, dry eyes, nauseas, blurred vision, etc.[7] Regarding psychiatric disorders, FMS patients usually display a high rate of mood and anxiety disorders compared to the general population, which could increase their disability and mortality, as well as reduce health-related quality of life in these patients.[8][9][10] See table 1 for more details.

Table 1.

Psychiatric disorders in FMS.

|

Common Psychiatric disorders in FMS |

|

Depressive disorders [11][12][13] |

|

Major depressive disorder [14][15][16][17][18] |

|

Anxiety and Generalized anxiety disorder [11][12][13][19][20] |

|

Phobias including kinesiophobia [21][22] |

|

Obsessive compulsive disorder [21][23][24][25] |

|

Post-traumatic stress disorder [26][27][14][20] |

|

Bipolar disorders [14][30][31][32] |

On the other hand, FMS is related to a high socioeconomic cost for the health system (more medical visits, diagnostic tests, and prescriptions) and the work-related field (less productivity, more sick leaves).[9][33]

In FMS, there is a prevalence not only of clinical but also emotional symptoms. In this sense, pain and emotions are closer in anatomic terms, given that they share some brain circuits [34][35] and have a common neural alarm system.[36][37] Therefore, it is necessary to improve the understanding of the role of emotion and affect in clinical practice, especially in chronic pain patients.

2. Effect of FMS

FMS has been associated with higher levels of negative affect and lower levels of positive affect.[38][39][40][41] Negative affect comprises greater distress and the presence of aversive emotions and states such as sadness or sorrow, anxiety, fear, disgust, low motivation, nervousness, anger, and guilt among others.[42] Positive affect includes pleasant feelings and states, for instance, enthusiasm, optimism, serenity, high energy, and full concentration.[42] The intensity of negative affect in FMS seems to be related to increased pain intensity, cognitive impairments, tiredness, annoyance, physical and mental stress, daily activities limitations, augmented disabilities, comorbidities, insomnia and sleep troubles, reduced health-related quality of life, and negative pain coping strategies.[9][13][43]

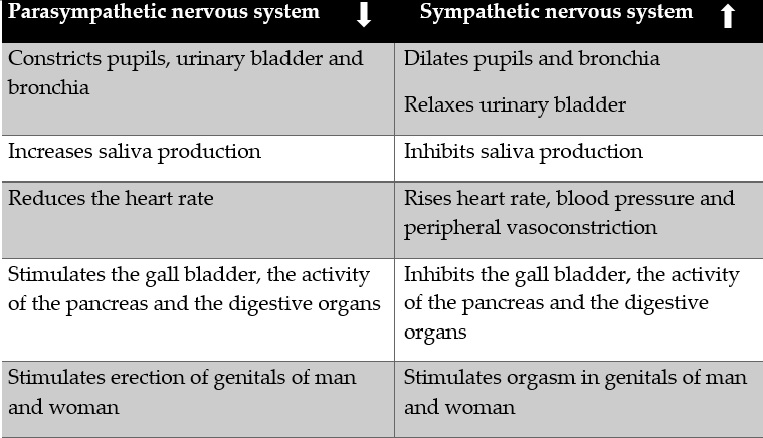

In addition, high levels of stress have been reported in FMS.[44][45][46][47][48][49] Furthermore, different studies have explored the relation between exposure to stressors (especially early stressors during childhood and puberty), alterations in mechanisms of the stress response, and the later development of FMS. These studies found alterations of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathetic nervous system (see Table 2) in FMS and related conditions.[50][51] Furthermore, stress appear to contribute to the onset and worsening of psychiatric and somatic symptoms in FMS patients.[52] In addition, stress might elicit pain in FMS[44][48][53] suggesting the need to train patients in coping stress techniques.

Table 2.

Effects of parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system activation.

With respect to anger in FMS, studies have found higher levels of anger, especially angry rumination.[54][55][56] Anger rumination can be defined as a particular form of anger expression which implies perseverative thoughts about experiences of anger that emerge during and after the experience of a negative emotion.[57] [58] Anger rumination includes four different cognitive processes: I) anger afterthoughts (thoughts that keep anger and mentally review the anger incident), II) anger memories (provoked by injustices experienced in the past), III) fantastic thoughts about revenge and, IV) trying to understand causes (counterfactual thoughts focus on the causes of the anger-provoking event).[58] Anger ruminations is also associated with lower mental health and health-related quality of life in FMS, compared to healthy individuals.[56] In the same line, it has been suggested that FMS patients might use worry and rumination as dysfunctional coping strategies to deal with their negative emotions.[54]

Anger can be also divided into anger-in or anger suppression, and anger-out or anger expression through verbal or physical means.[59] In this sense, anger toward oneself (anger-in) seems to be greater in FMS than rheumatoid arthritis patients[60][61] and healthy participants.[61] Although chronic pain patients usually experience anger, some studies alert that anger in this population might be underestimated because of patients tend to deny anger in their lives,[62] especially women, due to social rules usually discourage anger expression in them.[63] Additionally, there are a tendency to internalize and suppress anger in FMS patients[55][60][64] which might be worsening their symptoms and health-related quality of life. Anger might also increase pain perception and could provoke pain-relevant physiologic reactivity and muscle tension,[65][66] which confirms the need to identify and treat anger in these patients.

Pain catastrophizing is another important aspect which is generally presented in FMS.[67][68][69][70] Pain catastrophizing can be conceptualized as a negative emotion-focused coping strategy used in the framework of pain, which implies an exaggeratedly negative orientation to pain that causes fear, uneasiness, concerns and despair[71] and might contribute to stablish a vicious circle of increased pain and associated symptoms in FMS. Magnification, helplessness and rumination are the three major dimensions of pain catastrophizing.[71] Previous studies have found that pain catastrophizing in FMS is associated with a decrease in health-related quality of life,[68] illness exacerbation, poor treatment outcomes, loss of functionality and chronicity,[67][69][70][72] and an increase in the use of analgesics and healthcare resources.[67][73]

Regarding personality in FMS, there are not consensus between experts. On the one hand, some studies have found characteristic FMS traits such as negative affect, neuroticism, alexithymia, etc.[40][74][75][76] On the other hand, other authors do not found any particular personality characteristic.[77][78] Personality studies in this field has been predominantly focus on three models: the Big Five Model of Personality, the Cloninger’s Personality Model and the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles (MMPI).

Related to the Big Five Model of Personality, it comprises de following five dimensions:[79] I) Extraversion vs. Introversion. II) Agreeableness vs. Antagonism. III) Conscientiousness vs. Impulsivity. IV) Neuroticism vs. Emotional stability. V) Openness vs. Closed-mindedness.

Following this model, some researchers have found high impulsivity and neuroticism, and low conscientiousness in FMS.[79] Moreover, in some FMS patients the neuroticism might be accompanied by low levels of extraversion.[41][76] At the same time, lower levels of neuroticism have been related to more self-reported pain,[80] greater FMS and symptom severity, anxiety, depression and stress, worse mental component health-related quality of life, and lower self-efficacy and social support.[78] Extraversion in FMS has been previously related to lower pain, anxiety, and depression, and higher mental health-related quality of life.[78][81] Another study found that neuroticism and conscientiousness were significant predictors of pain catastrophizing, whereas neuroticism, openness, and agreeableness were significant predictors of pain anxiety.[82] A recent study has found that FMS patients were more agreeable and conscientious than general population and healthy participants.[83]

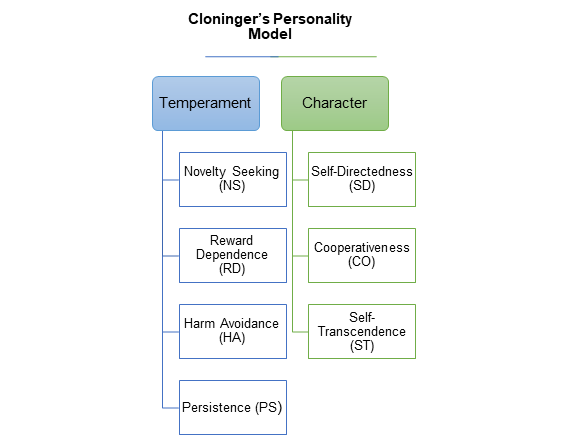

Related to the psychobiological Cloninger’s Personality Model (see Figure 1), it is focus on temperament and character.[84] Based on this model, some authors have reported in FMS high levels of harm avoidance and self-transcendence, and lower levels of cooperativeness and self-directedness,[45][85][86][87][88] together with persistence and reward dependence.[74] A decreased in novelty seeking has been also found in FMS patients.[89] Previous studies have shown that high harm avoidance and low self-directedness are personality features in chronic pain patients, for instance, in FMS, migraine, temporomandibular disorders and trigeminal neuropathy.[90][91] Therefore, it would be necessary to assess this personality dimensions in clinical practice to tailor treatments and better understand the disease experience of chronic pain patients.

Figure 1. Outline of the Cloninger’s Personality Model.

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory profiles (MMPI) have been other common questionnaire used in FMS. Based on this instrument, some researchers have found a different and worse personality profile in FMS compared to healthy participants.[75][92][93][94] Some authors have suggested that the FMS profile was characterized by more physical/functional limitations and psychosocial difficulties compared to other pain diseases, such as upper extremity pain, cervical pain, thoracic pain, lumbar pain, lower extremity pain, and headache.[95] A predominance of the psychosomatic profiles was also reported in FMS.[96] It has been also shown high levels of introversion, neuroticism and depression in FMS using this instrument.[96][97]

On the other hand, some personality disorders seem to be more frequent in FMS patients than in healthy individuals, especially obsessive-compulsive personality disorder,[98][21][24] borderline personality,[21][31][99] avoidant personality disorder,[100][101] and histrionic personality disorder.[21][102]

Type D personality appear to be more frequent in FMS than in general population[103][104][105] and cardiovascular and chronic pain patients.[105] The distressed type, or Type D personality, can be conceptualized as a combination of tendencies to experience negative emotions (negative affectivity) and to inhibit their expression owing to fear of disapproval (social inhibition).[106] Additionally, Type D personality in FMS has been associated with a poorer mental and physical health,[103][105] higher FMS severity, pain severity, fatigue, decrease in functional status and health-related quality of life,[105] and a less adaptive pattern.[74] In other research, Type D personality has also related to social phobia, dysthymia, and compulsive and/or avoidant personality disorders.[104]

Patients with FMS also exhibit high levels of alexithymia.[107][108][109][110][111][112] Alexithymia can be defined as a personality trait associated with difficulties in the cognitive processing of emotions which implies a lack of emotional awareness, troubles in identifying and communicating feelings and an externally oriented thinking pattern.[113] Different researchers have found in FMS associations between alexithymia and increased pain severity and disability and reduced health-related quality of life,[110][111][114] greater levels of depression,[112] and more cognitive deficits.[39] Alexithymia also has a negative influence on physical and mental components of health-related quality of life, through the mediation of depressive symptoms.[115] In addition, alexithymia (specifically difficulty identifying feelings factor) appear to be a significant predict of the affective dimension of pain, and this relation between alexithymia and affective pain seems to be mediated by the effect of anxiety.[109]

The research about personality in FMS need to continue in order to better understand the disease and propose more adjusted treatment. The relevance of personality studies in the context of chronic pain might be explained through the integrative biopsychosocial model, in which psychological aspects (i.e., personality) might act as predisposing factors to FMS.[40][49][116] Moreover, FMS patients who have personality disorders and/or negative personality traits, generally get worse results after pain treatment,[117][118] have a worse psychological health and poor social relationships,[119] and have a greater consumption of medical and socioeconomic resources.[101][119] However, it is necessary to keep in mind that FMS patients are probably a heterogeneous group regarding personality and psychopathology profiles.[97]

3. Conclusions

To sum up, pain and emotions are closer in anatomic and psychological terms. Therefore, it is necessary to improve the understanding of the role of emotion and affect in clinical practice, especially in chronic pain patients. It is well known that negative emotions could increase nociception,[34][120] hypervigilance, worry about symptoms, misinterpretation of arousal from somatic sources, and inadequate behaviors and coping strategies, for instance, avoidance.[16] It is also important to take the personality of FMS patients into account, because personality appear to facilitate the conversion of daily situations in stressors, which activate physiological responses and exacerbate FMS symptoms.[40] Based on the diathesis-stress model of illness, it is widely accepted that personality and psychopathology traits may become individuals more vulnerable to stressors and make the activation of patients’ vulnerabilities easier, contributing to the onset, development and maintenance of FMS.[121] Therefore, FMS treatments can be more effective if they are adjusted to FMS patients’ characteristics. In fact, the recommendations of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) for FMS insist that treatments should be tailored to the specific needs of each FMS patient and to involve psychological therapies, especially for mood disorders and negative coping strategies.[122]

References

- Frederick Wolfe; Hugh A. Smythe; Muhammad B. Yunus; Robert M. Bennett; Claire Bombardier; Don L. Goldenberg; Peter Tugwell; Stephen Campbell; Micha Abeles; Patricia Clark; et al.Adel G. FamStephen J. FarberJustus J. FiechtnerC. Michael FranklinRobert A. GatterDaniel HamatyJames LessardAlan S. LichtbrounAlfonse T. MasiGlenn A. McCainW. John ReynoldsThomas J. RomanoI. Jon RussellRobert P. Sheon The american college of rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 1990, 33, 160-172, 10.1002/art.1780330203.

- Sachin Srinivasan; Eamon Maloney; Brynn Wright; Michael Kennedy; K. James Kallail; Johannes J. Rasker; Winfried Häuser; Frederick Wolfe; The Problematic Nature of Fibromyalgia Diagnosis in the Community.. ACR Open Rheumatology 2019, 1, 43-51, 10.1002/acr2.1006.

- Frederick Wolfe; Brian Walitt; Serge Perrot; Johannes J. Rasker; Winfried Häuser; Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: Sex, prevalence and bias. PLOS ONE 2018, 13, e0203755, 10.1371/journal.pone.0203755.

- Roland Staud; Euna Koo; Michael E. Robinson; Donald D. Price; Spatial summation of mechanically evoked muscle pain and painful aftersensations in normal subjects and fibromyalgia patients. PAIN 2007, 130, 177-187, 10.1016/j.pain.2007.03.015.

- Richard H. Gracely; Frank Petzke; Julie M. Wolf; Daniel Clauw; Functional magnetic resonance imaging evidence of augmented pain processing in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 2002, 46, 1333-1343, 10.1002/art.10225.

- Robert S. Katz; Amy R. Heard; Megan Mills; Frank Leavitt; The Prevalence and Clinical Impact of Reported Cognitive Difficulties (Fibrofog) in Patients With Rheumatic Disease With and Without Fibromyalgia. JCR: Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2004, 10, 53-58, 10.1097/01.rhu.0000120895.20623.9f.

- Frederick Wolfe; Daniel J. Clauw; Mary-Ann Fitzcharles; Don L. Goldenberg; Robert S. Katz; Philip Mease; Anthony S. Russell; I. Jon Russell; John B. Winfield; Muhammad B. Yunus; et al. The American College of Rheumatology Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria for Fibromyalgia and Measurement of Symptom Severity. Arthritis Care & Research 2010, 62, 600-610, 10.1002/acr.20140.

- Dennis C Ang; Hyon Choi; Kurt Kroenke; Frederick Wolfe; Comorbid depression is an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.. The Journal of Rheumatology 2005, 32, 1013-9.

- Lesley M. Arnold; Leslie J. Crofford; Philip J. Mease; Somali Misra Burgess; Susan C. Palmer; Linda Abetz; Susan A. Martin; Patient perspectives on the impact of fibromyalgia. Patient Education and Counseling 2008, 73, 114-120, 10.1016/j.pec.2008.06.005.

- L Bazzichi; J Maser; A Piccinni; P Rucci; A Del Debbio; L Vivarelli; M Catena; S Bouanani; G Merlini; S Bombardieri; et al.L Dell'osso Quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis: impact of disability and lifetime depressive spectrum symptomatology.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2006, 23, 783-8.

- Fietta, P., Fietta, P., & Manganelli, P.; Fibromyalgia and psychiatric disorders.. Acta bio-medica: Atenei Parmensis 2007, 78(2), 88–95.

- Selen Işık Ulusoy; Evaluation of affective temperament and anxiety-depression levels in fibromyalgia patients: a pilot study. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 41, 428-432, 10.1590/1516-4446-2018-0057.

- Kati Thieme; Dennis C. Turk; Herta Flor; Comorbid Depression and Anxiety in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Relationship to Somatic and Psychosocial Variables. Psychosomatic Medicine 2004, 66, 837-844, 10.1097/01.psy.0000146329.63158.40.

- Mauro Giovanni Carta; Maria Francesca Moro; Francesca Laura Pinna; Giorgia Testa; Enrico Cacace; Valeria Ruggiero; Martina Piras; Ferdinando Romano; Luigi Minerba; Sergio Machado; et al.Rafael C.R. FreireAntonio Egidio NardiFederica Sancassiani The impact of fibromyalgia syndrome and the role of comorbidity with mood and post-traumatic stress disorder in worsening the quality of life. International Journal of Social Psychiatry 2018, 64(7), 647–655, 10.1177/0020764018795211.

- Lydia Gómez-Pérez; Alvaro Vergés; Ana Rocío Vázquez-Taboada; Josefina Durán; Matías González Tugas; The efficacy of adding group behavioral activation to usual care in patients with fibromyalgia and major depression: design and protocol for a randomized clinical trial. Trials 2018, 19, 660, 10.1186/s13063-018-3037-1.

- Janssens, K. A., Zijlema, W. L., Joustra, M. L., & Rosmalen, J. G.; Mood and Anxiety Disorders in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, Fibromyalgia, and Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Results from the Life Lines Cohort Study.. Psychosomatic Medicine 2015, 77(4), 449–457, 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000161.

- J.S. Løge-Hagen; A. Sæle; C. Juhl; P. Bech; E. Stenager; Angelina Isabella Mellentin; Prevalence of depressive disorder among patients with fibromyalgia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2019, 245, 1098-1105, 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.001.

- Jennifer L. Steiner; Silvia M. Bigatti; James E. Slaven; Dennis C. Ang; The Complex Relationship between Pain Intensity and Physical Functioning in Fibromyalgia: The Mediating Role of Depression. Journal of Applied Biobehavioral Research 2017, 22, 618, 10.1111/jabr.12079.

- Tonguc D. Berkol; Yasin H. Balcioglu; Simge S. Kirlioglu; Habib Erensoy; Meltem Vural; Dissociative features of fibromyalgia syndrome. Neurosciences 2017, 22, 198-204, 10.17712/nsj.2017.3.20160538.

- Daniel J. Clauw; Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1547-1555, 10.1001/jama.2014.3266.

- Faruk Uguz; Erdinç Çíçek; Ali Salli; Ali Yavuz Karahan; Ilknur Albayrak; Nazmiye Kaya; Hatice Ugurlu; Axis I and Axis II psychiatric disorders in patients with fibromyalgia. General Hospital Psychiatry 2010, 32, 105-107, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.002.

- Anneleen Malfliet; Jessica Van Oosterwijck; Mira Meeus; Barbara Cagnie; Lieven Danneels; Mieke Dolphens; Ronald Buyl; Jo Nijs; Kinesiophobia and maladaptive coping strategies prevent improvements in pain catastrophizing following pain neuroscience education in fibromyalgia/chronic fatigue syndrome: An explorative study. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice 2017, 33, 653-660, 10.1080/09593985.2017.1331481.

- Luigi Attademo; Francesco Bernardini; Prevalence of personality disorders in patients with fibromyalgia: a brief review. Primary Health Care Research & Development 2017, 19, 523-528, 10.1017/S1463423617000871.

- Sébastien Rose; O. Cottencin; Vincent Chouraki; Jean-Michel Wattier; Éric Houvenagel; Benoit Vallet; Michel Goudemand; Importance des troubles de la personnalité et des comorbidités psychiatriques chez 30 patients atteints de fibromyalgie. La Presse Médicale 2009, 38, 695-700, 10.1016/j.lpm.2008.11.013.

- Pando Fernández M.P.; Fibromyalgia and psychotherapy. Revista Digital de Medicina Psicosomática y Psicoterapia 2011, 1, 1–42.

- Ciro Conversano; Claudia Carmassi; Carlo A Bertelloni; Laura Marchi; Tommaso Micheloni; Manuel G Carbone; Giovanni Pagni; Claudia Tagliarini; Gabriele Massimetti; Laura M Bazzichi; et al.Liliana Dell'osso Potentially traumatic events, post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic stress spectrum in patients with fibromyalgia.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2018, 37 Suppl 116(1), 39-43.

- E. Coppens; P. Van Wambeke; B. Morlion; N. Weltens; H. Giao Ly; J. Tack; P. Luyten; Lukas Van Oudenhove; Prevalence and impact of childhood adversities and post-traumatic stress disorder in women with fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. European Journal of Pain 2017, 21, 1582-1590, 10.1002/ejp.1059.

- Kenji Miki; Aya Nakae; Kenrin Shi; Yuka Yasuda; Hidenaga Yamamori; Michiko Fujimoto; Manabu Ikeda; Masahiko Shibata; Masao Yukioka; Ryota Hashimoto; et al. Frequency of mental disorders among chronic pain patients with or without fibromyalgia in Japan. Neuropsychopharmacology Reports 2018, 38, 167-174, 10.1002/npr2.12025.

- Alberto Soriano-Maldonado; Kirstine Amris; Francisco B. Ortega; Víctor Segura-Jiménez; Fernando Estévez-López; Inmaculada C. Álvarez-Gallardo; Virginia A. Aparicio; Manuel Delgado-Fernández; Marius Henriksen; Jonatan R. Ruiz; et al. Association of different levels of depressive symptoms with symptomatology, overall disease severity, and quality of life in women with fibromyalgia. Human Genetics 2015, 24, 2951-2957, 10.1007/s11136-015-1045-0.

- Carmen E Gota; Sahar Kaouk; William S. Wilke; The impact of depressive and bipolar symptoms on socioeconomic status, core symptoms, function and severity of fibromyalgia. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2015, 20, 326-339, 10.1111/1756-185x.12603.

- Alessandra Alciati; Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini; Alberto Batticciotto; Riccardo Torta; Felice Gesuele; Fabiola Atzeni; Jules Angst; Overactive lifestyle in patients with fibromyalgia as a core feature of bipolar spectrum disorder.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2012, 30(6 Suppl 74), 122–128.

- M C Di Tommaso Morrison; F Carinci; G Lessiani; E Spinas; S K Kritas; G Ronconi; Al Caraffa; P Conti; Fibromyalgia and bipolar disorder: extent of comorbidity and therapeutic implications.. Journal of biological regulators and homeostatic agents 2017, 31, 17-20.

- Michael Spaeth; Epidemiology, costs, and the economic burden of fibromyalgia.. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2009, 11, 117-117, 10.1186/ar2715.

- Gina A. Mollet; David W. Harrison; Emotion and Pain: A Functional Cerebral Systems Integration. Neuropsychology Review 2006, 16, 99-121, 10.1007/s11065-006-9009-3.

- M. Duquette; M. Roy; F. Lepore; I. Peretz; P. Rainville; Mécanismes cérébraux impliqués dans l’interaction entre la douleur et les émotions. Revue Neurologique 2007, 163, 169-179, 10.1016/s0035-3787(07)90388-4.

- Francesca Benuzzi; Fausta Lui; Davide Duzzi; Paolo Nichelli; Carlo Porro; Does It Look Painful or Disgusting? Ask Your Parietal and Cingulate Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience 2008, 28, 923-931, 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4012-07.2008.

- Petra Schweinhardt; Nicola Kalk; Karolina Wartolowska; Iain Chessell; Paul Wordsworth; Irene Tracey; Investigation into the neural correlates of emotional augmentation of clinical pain. NeuroImage 2008, 40, 759-766, 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.12.016.

- Patrick H. Finan; Alex J. Zautra; Mary C. Davis; Daily Affect Relations in Fibromyalgia Patients Reveal Positive Affective Disturbance. Psychosomatic Medicine 2009, 71, 474-482, 10.1097/psy.0b013e31819e0a8b.

- Carmen M. Galvez-Sánchez; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Stefan Duschek; Cognitive Impairments in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Associations With Positive and Negative Affect, Alexithymia, Pain Catastrophizing and Self-Esteem. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 377, 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00377.

- Katrina Malin; Geoffrey O Littlejohn; Stress modulates key psychological processes and characteristic symptoms in females with fibromyalgia.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2013, 31(6 Suppl 79), S64–S71.

- Alex J. Zautra; Robert Fasman; John W. Reich; Peter Harakas; Lisa M. Johnson; Maureen E. Olmsted; Mary C. Davis; Fibromyalgia: Evidence for Deficits in Positive Affect Regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine 2005, 67, 147-155, 10.1097/01.psy.0000146328.52009.23.

- David Watson; Lee A. Clark; Auke Tellegen; Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales.. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1988, 54, 1063-1070, 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063.

- Faruk Uguz; Erdinç Çíçek; Ali Salli; Ali Yavuz Karahan; Ilknur Albayrak; Nazmiye Kaya; Hatice Ugurlu; Axis I and Axis II psychiatric disorders in patients with fibromyalgia. General Hospital Psychiatry 2010, 32, 105-107, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.002.

- Eline Coppens; Stefan Kempke; Peter Van Wambeke; Stephan Claes; Bart Morlion; Patrick Luyten; Lukas Van Oudenhove; Cortisol and Subjective Stress Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress in Fibromyalgia Patients and Control Participants. Psychosomatic Medicine 2018, 80, 317-326, 10.1097/psy.0000000000000551.

- Y Glazer; H Cohen; D Buskila; R P Ebstein; L Glotser; L Neumann; Are psychological distress symptoms different in fibromyalgia patients compared to relatives with and without fibromyalgia?. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2010, 27(5 Suppl 56), S11–S15.

- Mika Kivimaki; Päivi Leino-Arjas; Marianna Virtanen; Marko Elovainio; Liisa Keltikangas-Järvinen; Sampsa Puttonen; Maarit Vartia; Eric Brunner; Jussi Vahtera; Work stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2004, 57, 417-422, 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.10.013.

- John McBeth; Alan J. Silman; The role of psychiatric disorders in fibromyalgia.. Current Rheumatology Reports 2001, 3, 157-164, 10.1007/s11926-001-0011-8.

- Monika Salgueiro; Zigor Aira; Itsaso Buesa; Juan Bilbao; Jon Jatsu Azkue; Is psychological distress intrinsic to fibromyalgia syndrome? Cross-sectional analysis in two clinical presentations. Rheumatology International 2011, 32, 3463-3469, 10.1007/s00296-011-2199-x.

- Boudewijn Van Houdenhove; Patrick Luyten; Ulrich Tiber Egle; Stress as a Key Concept in Chronic Widespread Pain and Fatigue Disorders. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 2009, 17, 390-399, 10.3109/10582450903284745.

- Leslie J. Crofford; Mark A. Demitrack; EVIDENCE THAT ABNORMALITIES OF CENTRAL NEUROHORMONAL SYSTEMS ARE KEY TO UNDERSTANDING FIBROMYALGIA AND CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 1996, 22, 267-284, 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70272-6.

- Manuel Martínez-Lavín; Jesus Antonio Gonzalez-Hermosillo; Autonomic nervous system dysfunction may explain the multisystem features of fibromyalgia. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2000, 29, 197-199, 10.1016/s0049-0172(00)80008-6.

- Leslie J. Crofford; The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis in the pathogenesis of rheumatic diseases. Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America 2002, 31, 1-13, 10.1016/s0889-8529(01)00004-4.

- Ulla Marie Anderberg; Fibromyalgia syndrome in women - A stress disorder? Neurobiological and hormonal aspects. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 1999, 53, 389-389, 10.1080/080394899427908.

- A. Ricci; S. Bonini; M. Continanza; M.T. Turano; E.M. Puliti; A. Finocchietti; D. Bertolucci; Worry and anger rumination in fibromyalgia syndrome. Reumatismo 2016, 68, 195, 10.4081/reumatismo.2016.896.

- H. Van Middendorp; Mark A. Lumley; Johannes W. G. Jacobs; Johannes W. J. Bijlsma; Rinie Geenen; The effects of anger and sadness on clinical pain reports and experimentally-induced pain thresholds in women with and without fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care & Research 2010, 62, 1370-1376, 10.1002/acr.20230.

- Loren Toussaint; Fuschia Sirois; Jameson Hirsch; Niko Kohls; Annemarie Weber; Joerg Schelling; Christian Vajda; Martin Offenbäecher; Anger rumination mediates differences between fibromyalgia patients and healthy controls on mental health and quality of life. Personality and Mental Health 2019, 13, 119-133, 10.1002/pmh.1445.

- Thomas F. Denson; The Multiple Systems Model of Angry Rumination. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2012, 17, 103-123, 10.1177/1088868312467086.

- Denis G. Sukhodolsky; Arthur Golub; Erin N. Cromwell; Development and validation of the anger rumination scale. Personality and Individual Differences 2001, 31, 689-700, 10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00171-9.

- Spielberger, C.D, Jacobs, G, Russel, S, & Crane, R.S.. Assessment of anger: the state-trait anger scale. In: JN Butcher, Spielberger CD (eds) Advances in personality assessment, vol 2; Lawrence Erlbaum.: Hillsdale, 1983; pp. 159–186.

- Kemal Sayar; Huseyin Gulec; Murat Topbas; Alexithymia and anger in patients with fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology 2004, 23, 441-448, 10.1007/s10067-004-0918-3.

- Güleç, H., Sayar, K., Topbaş, M., Karkucak, M., & Ak, I.; Fibromiyalji Sendromu Olan Kadinlarda Aleksitimi ve Ofke [Alexithymia and anger in women with fibromyalgia syndrome]. . Turk psikiyatri dergisi = Turkish journal of psychiatry 2004, 15(3), 191–198.

- Ephrem Fernandez; The relationship between anger and pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2005, 9, 101-105, 10.1007/s11916-005-0046-z.

- Laura S. Porter; Arthur A. Stone; J. E. Schwartz; Anger Expression and Ambulatory Blood Pressure. Psychosomatic Medicine 1999, 61, 454-463, 10.1097/00006842-199907000-00009.

- Alberto Amutio; Clemente Franco; Marãa De Carmen Pã©Rez-Fuentes; Josã© J. Gã¡zquez; Isabel Mercader; María De Carmen Pérez-Fuentes; José J. Gázquez; Mindfulness training for reducing anger, anxiety, and depression in fibromyalgia patients. Frontiers in Psychology 2015, 5, 1572, 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01572.

- S A Janssen; Philip Spinhoven; Jos F Brosschot; Experimentally induced anger, cardiovascular reactivity, and pain sensitivity.. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2001, 51, 479-485, 10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00222-7.

- Albert F. Ax; The Physiological Differentiation between Fear and Anger in Humans. Psychosomatic Medicine 1953, 15, 433-442, 10.1097/00006842-195309000-00007.

- R.R. Edwards; Clifton O. Bingham; Joan Bathon; Jennifer A. Haythornthwaite; Catastrophizing and pain in arthritis, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatic diseases. Arthritis Care & Research 2006, 55, 325-332, 10.1002/art.21865.

- Carmen M. Galvez-Sánchez; Casandra I. Montoro; Stefan Duschek; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Pain catastrophizing mediates the negative influence of pain and trait-anxiety on health-related quality of life in fibromyalgia. Quality of Life Research 2020, 29, 1871-1881, 10.1007/s11136-020-02457-x.

- Cory Toth; Shauna Brady; Melinda Hatfield; The importance of catastrophizing for successful pharmacological treatment of peripheral neuropathic pain. Journal of Pain Research 2014, 7, 327-338, 10.2147/JPR.S56883.

- C. Paul Van Wilgen; Miriam W. Van Ittersum; Ad A. Kaptein; Marten Van Wijhe; Illness perceptions in patients with fibromyalgia and their relationship to quality of life and catastrophizing. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2008, 58, 3618-3626, 10.1002/art.23959.

- Michael Jl. Sullivan; Beverly Thorn; Jennifer A. Haythornthwaite; Francis Keefe; Michelle Martin; Laurence Bradley; John C. Lefebvre; Theoretical Perspectives on the Relation Between Catastrophizing and Pain. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2001, 17, 52-64, 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008.

- Baltasar Rodero Fernández; Javier Garcia Campayo; Benigno Casanueva; Yolanda Buriel; Tratamientos no farmacológicos en fibromialgia : una revisión actual. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica 2009, 14, 137-151, 10.5944/rppc.vol.14.num.3.2009.4074.

- R. H. Gracely; M. E. Geisser; T. Giesecke; M. A. B. Grant; F. Petzke; D. A. Williams; Daniel Clauw; Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain 2004, 127, 835-843, 10.1093/brain/awh098.

- Jacob Ablin; Ada H. Zohar; Reut Zaraya-Blum; Dan Buskila; Distinctive personality profiles of fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome patients. PeerJ 2016, 4, e2421, 10.7717/peerj.2421.

- R. Novo; B. Gonzalez; R. Peres; P. Aguiar; Corrigendum to “A meta-analysis of studies with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory in fibromyalgia patients” [Personal. Individ. Differ., 116 (2017), 96–108]. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 119, 354, 10.1016/j.paid.2017.07.022.

- Xavier Torres; Eva Bailles; Manuel Valdés; Fernando Gutiérrez; Josep-Maria Peri; Anna Arias; Emili Gómez; Antonio Collado; Personality does not distinguish people with fibromyalgia but identifies subgroups of patients. General Hospital Psychiatry 2013, 35, 640-648, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2013.07.014.

- Valur Johannsson; Does a Fibromyalgia Personality Exist?. Journal of Musculoskeletal Pain 1993, 1, 245-252, 10.1300/j094v01n03_26.

- Andrew Seto; Xingyi Han; Lori Lyn Price; William F. Harvey; Raveendhara R. Bannuru; Chenchen Wang; The role of personality in patients with fibromyalgia. Clinical Rheumatology 2018, 38, 149-157, 10.1007/s10067-018-4316-7.

- Emilie Bucourt; Virginie Martaillé; D. Mulleman; P Goupille; Isabelle Joncker-Vannier; Brigitte Huttenberger; Christian Reveillere; R. Courtois; Comparison of the Big Five personality traits in fibromyalgia and other rheumatic diseases. Joint Bone Spine 2017, 84, 203-207, 10.1016/j.jbspin.2016.03.006.

- Emilie Bucourt; Virginie Martaillé; Denis Mulleman; P Goupille; Isabelle Joncker-Vannier; Brigitte Hüttenberger; Christian Reveillere; R. Courtois; Comparaison des cinq grands traits de personnalité dans la fibromyalgie et les autres maladies rhumatismales. Revue du Rhumatisme 2018, 85, 188-194, 10.1016/j.rhum.2017.07.008.

- Casandra I. Montoro; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Personality and fibromyalgia: Relationships with clinical, emotional, and functional variables. Personality and Individual Differences 2015, 85, 236-244, 10.1016/j.paid.2015.05.017.

- María Pilar Martínez; Ana Isabel Sánchez; Elena Miró; Ana Medina; María José Lami; The Relationship Between the Fear-Avoidance Model of Pain and Personality Traits in Fibromyalgia Patients. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 2011, 18, 380-391, 10.1007/s10880-011-9263-2.

- Weronika Bartkowska; Włodzimierz Samborski; Ewa Mojs; Cognitive functions, emotions and personality in woman with fibromyalgia. Anthropologischer Anzeiger 2018, 75, 271-277, 10.1127/anthranz/2018/0900.

- Cloninger, C.. Personality and psychopathology. ; American Psychiatric Press, Inc.: Washington, DC., 1999; pp. 524.

- Özlem Balbaloğlu; Nermin Tanik; Mahmut Alpayci; Hakan Ak; Elif Karaahmet; Levent Ertugrul Inan; Paresthesia frequency in fibromyalgia and its effects on personality traits. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases 2018, 21, 1343-1349, 10.1111/1756-185x.13336.

- Alba Garcia-Fontanals; Mariona Portell; Susanna García-Blanco; Violant Poca-Dias; Ferran García-Fructuoso; Marina López-Ruiz; María Teresa Gutiérrez Rosado; Montserrat Gomà‐I‐Freixanet; Joan Deus; Vulnerability to Psychopathology and Dimensions of Personality in Patients With Fibromyalgia. The Clinical Journal of Pain 2017, 33, 991-997, 10.1097/ajp.0000000000000506.

- Asli Gencay-Can; Serdar Suleyman Can; Temperament and character profile of patients with fibromyalgia. Rheumatology International 2011, 32, 3957-3961, 10.1007/s00296-011-2324-x.

- Paolo Leombruni; Francesca Zizzi; Marco Miniotti; Fabrizio Colonna; Lorys Castelli; Enrico Fusaro; Riccardo Torta; Harm Avoidance and Self-Directedness Characterize Fibromyalgic Patients and the Symptom Severity. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2016, 7, 579, 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00579.

- Daniela M Santos; Laís V Lage; Eleonora K Jabur; Helena H S Kaziyama; Dan V Iosifescu; Mara Cristina S De Lucia; Renério Fráguas; The influence of depression on personality traits in patients with fibromyalgia: a case-control study.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2016, 35 Suppl 105(3), 13-19.

- Rupert Conrad; Ingo Wegener; Franziska Geiser; Alexandra Kleiman; Temperament, Character, and Personality Disorders in Chronic Pain. Current Pain and Headache Reports 2013, 17(3), 318, 10.1007/s11916-012-0318-3.

- Brooke Naylor; Simon Boag; Sylvia Maria Gustin; New evidence for a pain personality? A critical review of the last 120 years of pain and personality. Scandinavian Journal of Pain 2017, 17, 58-67, 10.1016/j.sjpain.2017.07.011.

- Rosa Novo; Barbara Gonzalez; Rodrigo Sanches Peres; Pedro Aguiar; A meta-analysis of studies with the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory in fibromyalgia patients. Personality and Individual Differences 2017, 116, 96-108, 10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.026.

- Claros, L., Cano, M., Presa, A., Barceló, J., Satamán, P., Roca, J., et al.; Perfiles clínicos en pacientes con fibromialgia que acuden a un centro de salud mental: Obtención de un índice predictivo de gravedad psicopatológica.. Actas Españolas De Psiquiatria 2006, 34, 112–122.

- David A. Fishbain; Robert Cutler; Hubert L. Rosomoff; Renee Steele Rosomoff; Chronic Pain-Associated Depression: Antecedent or Consequence of Chronic Pain? A Review. The Clinical Journal of Pain 1997, 13, 116-137, 10.1097/00002508-199706000-00006.

- Skye Porter-Moffitt; Robert J. Gatchel; Richard C. Robinson; Martin Deschner; Mette Posamentier; Peter Polatin; Leland Lou; Biopsychosocial Profiles of Different Pain Diagnostic Groups. The Journal of Pain 2006, 7, 308-318, 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.12.003.

- Ellertsen, B., Værøy, H., Endresen, I., & Førre, Ø.; MMPI in fibromyalgia and local nonspecific myalgia.. New Trends in Experimental & Clinical Psychiatry 1991, 7(2), 53–62.

- Bárbara Gonzalez; Rosa Novo; Ana Sousa Ferreira; Fibromyalgia: heterogeneity in personality and psychopathology and its implications. Psychology, Health & Medicine 2019, 25, 703-709, 10.1080/13548506.2019.1695866.

- Hellström Olle; Bullington Jennifer; Karlsson Gunnar; Lindqvist Per; Mattsson Bengt; A phenomenological study of fibromyalgia. Patient perspectives. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care 1999, 17, 11-16, 10.1080/028134399750002827.

- Sarah Penfold; Emily St. Denis; Mir Mazhar; The association between borderline personality disorder, fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue syndrome: systematic review. BJPsych Open 2016, 2, 275-279, 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.002808.

- Fu, T, Gamble, H, Siddiqui, U, & Schwartz, T.; Psychiatric and personality disorder survey of patients with fibromyalgia. . Annals Depres Anxiet. 2015 , 2, 1064.

- Laura Gumà-Uriel; María Peñarrubía-María; Marta Cerdà-Lafont; Oriol Cunillera; Jesús Almeda Ortega; Rita Fernández Vergel; Javier García-Campayo; Juan V. Luciano; Impact of IPDE-SQ personality disorders on the healthcare and societal costs of fibromyalgia patients: a cross-sectional study.. BMC Family Practice 2016, 17, 61, 10.1186/s12875-016-0464-5.

- Fatih Kayhan; Adem Kucuk; Yılmaz Satan; Erdem Ilgün; Şevket Arslan; Faik Ilik; Sexual dysfunction, mood, anxiety, and personality disorders in female patients with fibromyalgia. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 2016, 12, 349-355, 10.2147/NDT.S99160.

- Yeşim Garip; Tuba Güler; Özgül Bozkurt Tuncer; Sinay Önen; Yesim Garip; Type D Personality is Associated With Disease Severity and Poor Quality of Life in Turkish Patients With Fibromyalgia Syndrome: A Cross-Sectional Study. Archives of Rheumatology 2020, 35, 13-19, 10.5606/archrheumatol.2020.7334.

- Frank Lambertus; Christoph Herrmann-Lingen; Kurt Fritzsche; Stefanie Hamacher; Martin Hellmich; Jana Jünger; Karl Heinz Ladwig; Matthias Michal; Joram Ronel; Jobst-Hendrik Schultz; et al.Frank VitiniusCora WeberChristian Albus Prevalence of mental disorders among depressed coronary patients with and without Type D personality. Results of the multi-center SPIRR-CAD trial. General Hospital Psychiatry 2018, 50, 69-75, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.10.001.

- H. Van Middendorp; Marianne B. Kool; Sylvia Van Beugen; Johan Denollet; Mark A. Lumley; Rinie Geenen; Press Enter Key For Correspondence Information; Prevalence and relevance of Type D personality in fibromyalgia. General Hospital Psychiatry 2016, 39, 66-72, 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2015.11.006.

- Johan Denollet; DS14: Standard Assessment of Negative Affectivity, Social Inhibition, and Type D Personality. Psychosomatic Medicine 2005, 67, 89-97, 10.1097/01.psy.0000149256.81953.49.

- Lazslo A. Avila; Gerardo Maria De Araújo Filho; Estefano F.U. Guimarães; Lauro C.S. Gonçalves; Paola N. Paschoalin; Fabia B. Aleixo; Caracterização dos padrões de dor, sono e alexitimia em pacientes com fibromialgia atendidos em um centro terciário brasileiro. Revista Brasileira de Reumatologia 2014, 54, 409-413, 10.1016/j.rbr.2014.03.017.

- Marialaura Di Tella; Lorys Castelli; Alexithymia in Chronic Pain Disorders. Current Rheumatology Reports 2016, 18(7), 41, 10.1007/s11926-016-0592-x.

- Marialaura Di Tella; Ada Ghiggia; Valentina Tesio; Annunziata Romeo; Fabrizio Colonna; Enrico Fusaro; Riccardo Torta; Lorys Castelli; Pain experience in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: The role of alexithymia and psychological distress. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017, 208, 87-93, 10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.080.

- Lorys Castelli; Valentina Tesio; Fabrizio Colonna; Stefania Molinaro; Paolo Leombruni; Maria Bruzzone; Enrico Fusaro; Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini; Riccardo Torta; Alexithymia and psychological distress in fibromyalgia: prevalence and relation with quality of life.. Clinical and experimental rheumatology 2012, 30(6 Suppl 74), 70–77.

- Casandra I. Montoro; Gustavo A. Reyes Del Paso; Stefan Duschek; Alexithymia in fibromyalgia syndrome. Personality and Individual Differences 2016, 102, 170-179, 10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.072.

- Ada Ghiggia; Annunziata Romeo; Valentina Tesio; Marialaura Di Tella; Fabrizio Colonna; Giuliano Carlo Geminiani; Enrico Fusaro; Lorys Castelli; Alexithymia and depression in patients with fibromyalgia: When the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Psychiatry Research 2017, 255, 195-197, 10.1016/j.psychres.2017.05.045.

- R.Michael Bagby; James D.A. Parker; Graeme J. Taylor; The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia scale—I. Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 1994, 38, 23-32, 10.1016/0022-3999(94)90005-1.

- M. Pilar Martínez; Ana I. Sánchez; Elena Miró; María J. Lami; Germán Prados; Ana Morales; Relationships Between Physical Symptoms, Emotional Distress, and Pain Appraisal in Fibromyalgia: The Moderator Effect of Alexithymia. The Journal of Psychology 2014, 149, 115-140, 10.1080/00223980.2013.844673.

- Valentina Tesio; Marialaura Di Tella; Ada Ghiggia; Annunziata Romeo; Fabrizio Colonna; Enrico Fusaro; Giuliano C. Geminiani; Lorys Castelli; Alexithymia and Depression Affect Quality of Life in Patients With Chronic Pain: A Study on 205 Patients With Fibromyalgia. Frontiers in Psychology 2018, 9, 442, 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00442.

- M. Hartmann W. Eich; The role of psychosocial factors in fibromyalgia syndrome. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology 2000, 29, 30-31, 10.1080/030097400446607.

- Timothy R. Elliott; Warren T. Jackson; Molly Layfield; Debra Kendall; Personality disorders and response to outpatient treatment of chronic pain. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 1996, 3, 219-234, 10.1007/bf01993908.

- Jay M. Uomoto; Judith A. Turner; Larry D. Herron; Use of the MMPI and MCMI in predicting outcome of lumbar laminectomy. Journal of Clinical Psychology 1988, 44, 191-197, 10.1002/1097-4679(198803)44:2<191::aid-jclp2270440216>3.0.co;2-b.

- Faruk Uguz; Adem Kucuk; Erdinc Cicek; Fatih Kayhan; Ali Salli; Hatice Guncu; Ali Savas Cilli; Quality of life in rheumatological patients. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 2015, 49, 199-207, 10.1177/0091217415582183.

- Jamie L Rhudy; Amy E. Williams; Klanci M. McCabe; Philip L. Rambo; Jennifer L. Russell; Emotional modulation of spinal nociception and pain: The impact of predictable noxious stimulation. Pain 2006, 126, 221-233, 10.1016/j.pain.2006.06.027.

- Angeline S. Thiagarajah; Emma K. Guymer; Michelle Leech; Geoffrey O Littlejohn; The relationship between fibromyalgia, stress and depression. International Journal of Clinical Rheumatology 2014, 9, 371-384, 10.2217/ijr.14.30.

- Gary J. Macfarlane; C Kronisch; Linda Dean; F Atzeni; W Häuser; E Fluß; E Choy; E Kosek; K Amris; J Branco; et al.F DincerPäivi Leino-ArjasK LongleyGeraldine McCarthyS MakriS PerrotPiercarlo Sarzi-PuttiniA TaylorG T Jones EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2016, 76, 318-328, 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-209724.