Plant-dominant low-protein diet (LPD), also abbreviated as "PLADO" is a patient-centered LPD of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day composed of >50% plant-based sources, administered by dietitians trained in providing nutrition care to patients with non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease (CKD). PLADO's composition and meal plans can be designed and adjusted based on individualized needs and according to the principles of precision nutrition. The goal of PLADO is to slow kidney disease progression, to avoid or delay dialysis therapy initiation, and to ensure cardiovascular health and longevity. The ideal type of PLADO is a heart-healthy, safe, flexible, and feasible diet that could be the centerpiece of the conservative and preservative management of CKD.

- Low potein diet

- plant-dominant

- chronic kideny disease

- precision nutrition

- cardiovascular health

1. Definition

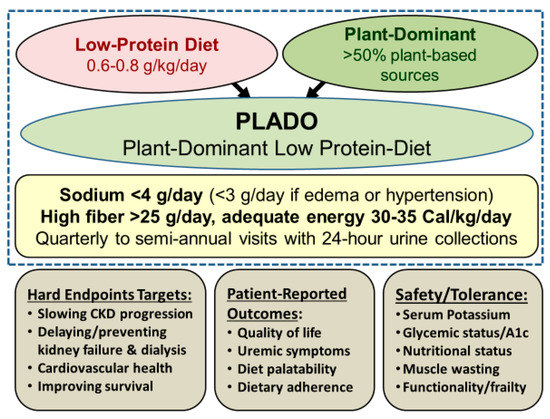

We define a plant-dominant LPD, also referred to as PLADO, as a type of LPD with DPI of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day with at least 50% plant-based sources to meet the targeted dietary protein, and which should preferably be whole, unrefined, and unprocessed foods (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of the plant-dominant low-protein diet (PLADO) for nutritional management of CKD, based on a total dietary intake of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day with >50% plant-based sources, preferentially unprocessed foods, relatively low dietary sodium intake <3 g/day (but the patient can target to avoid >4 g/day if no edema occurs with well controlled hypertension), higher dietary fiber of at least 25–30 g/day, and adequate dietary energy intake of 30–35 Cal/kg/day. Weight is based on the ideal body weight. Note that serum B12 should be monitored after three years of vegan dieting.

2. Introduction

This is consistent with the RDA of DPI of 0.8 g/kg/day, which has a high safety margin, given that based on established metabolic studies [13][1], the lowest DPI requirement to avoid catabolic changes is 0.45 to 0.5 g/kg/day. It has been suggested that ≥50% of DPI should be of “high biologic value” with high gastrointestinal absorbability to ensure adequate intake of essential amino acids [3][2]. However, other metrics, including the “protein digestibility-corrected amino-acid score,” which is a more accurate method recommended by the Food and Agricultural Organization and the World Health Organization, grant high scores to many plant-based sources and may be a more appropriate measure of protein quality [67][3]. Other features of PLADO include relatively low sodium intake <3 g/day, higher dietary fiber of at least 25–30 g/day, and adequate dietary energy intake (DEI) of 30–35 Cal/kg/day, assuming that the DEI calculations are based on the ideal body weight, similar to the approach to calculating DPI (Figure 1).

3. Benefits of a Plant-Dominant Low Protein Diet

There are multiple pathways by which an LPD with at least 50% plant-based protein sources ameliorates CKD progression, in addition to reducing glomerular hyperfiltration [33] [4](Table 1):

- Reduction in nitrogenous compounds leads to less production of ammonia and uremic toxins as an effective strategy in controlling uremia and delaying dialysis initiation [28].[5].

- Synergism with RAAS and SGLT2 inhibitors, since LPD reinforces the pharmaco-therapeutic effect of lowering intra-glomerular pressure through complementary mechanisms (Figure 1) [68].[6].

- Attenuation of metabolites derived from gut bacteria that are linked with CKD and CV disease: Animal protein ingredients including choline and carnitine are converted by gut flora into trimethylamine (TMA) and TMA N-oxide (TMAO) that are associated with atherosclerosis, renal fibrosis [69], and increased risk of CV disease and death [70]. The favorable impact on the gut microbiome [71] similarly leads to lower levels of other uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate [72].[7] [69], and increased risk of CV disease and death[8]. The favorable impact on the gut microbiome[9] similarly leads to lower levels of other uremic toxins such as indoxyl sulfate and p-cresol sulfate[10].

- Decreased acid load: plant foods have a lower acidogenicity in contrast to animal foods, and this alkalization may have additional effects beyond mere intake of natural alkali [73].[11].

- Reduced phosphorus burden: there is less absorbable phosphorus in plant-based proteins given the presence of indigestible phytate binding to plant-based phosphorus. Fruits and vegetables are less likely to have added phosphorus-based preservatives that are often used for meat processing [59,74–76].[12][13][14][15].

- Modulation of advanced glycation end products (AGE’s): higher dietary fiber intake results in a favorable modulation of AGE [77], which can slow CKD progression [78], enhance GI motility, and lower the likelihood of constipation that is a likely contributor to hyperkalemia.[16], which can slow CKD progression[17], enhance GI motility, and lower the likelihood of constipation that is a likely contributor to hyperkalemia.

- Favorable effects on potassium metabolism: a plant-based diet based on more whole fruits and vegetables lessens the likelihood of potassium-based additives that are often found in meat products [79,80].[18][19].

- Anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant effects: there is a decreased risk of CKD progression and CV disease due to higher intake of natural anti-inflammatory and antioxidant ingredients, including carotenoids, tocopherols, and ascorbic acid [81,82].[20][21].

Table 1.

Benefits and challenges of LPD with >50% plant-based protein sources.

|

Benefits of LPD with >50% Plant Sources |

Potential Challenges of LPD |

|

· Lowering intra-glomerular pressure |

· Risk of protein-energy wasting (PEW) |

|

· Synergistic effect with RAASi and SGLT2i |

· Inadequate essential amino acids |

|

· Controlling uremia and delaying dialysis |

· Undermining obesity management |

|

· Preventing cardiovascular harms of meat |

· High glycemic index |

|

· Less absorbable phosphorus |

· High potassium load and hyperkalemia |

|

· Lowering acid-load with less acidogenicity |

· Low palatability and adherence |

|

· High dietary fiber enhancing GI motility |

· Inadequate fish intake if vegan |

|

· Favorable changes in microbiome |

|

|

· Less TMA N-oxide (TMAO), leading to less kidney fibrosis |

|

|

· Less inflammation and oxidative stress |

|

4. Features of PLADO Regimens

As stated above, the plant-dominant restricted protein diet consists of an LPD amounting to 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day with at least 50% of the dietary protein being from plant-based sources. Table 42 compares PLADO with a standard diet in the USA, in that the total amount and proportion of plant-based protein is usually 1.2–1.4 g/kg/day and 20–30%, respectively, whereas the PLADO not only has less total protein of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day but it also includes 50% to 70% of plant-based sources for this restricted DPI goal. Hence, an 80 kg person with CKD, for instance, would be recommended to have 46 to 64 g of DPI per day, out of which 24 to 45 g will be from plant-based sources, while the rest is according to patient choice and preferences. As shown in Table 2, the total amount of animal-based protein under PLADO regimen is 14 to 32 g/day, which is less than half of the 68 to 83 g/day in the standard diet, but the patient also has the choice of being nearly or totally plant-based. There are different types of vegetarian diets [33][4]: (1) Vegan, or strict vegetarian (100% plant-based), diets that not only exclude meat, poultry, and seafood but also eggs and dairy products; (2) Lacto- and/or ovo-vegetarian diets that may include dairy products and/or eggs; (3) Pesco-vegetarian diets that include a vegetarian diet combined with occasional intake of some or all types of sea-foods, mostly fish; and (4) Flexitarians, which is mostly vegetarian of any of the above types with occasional inclusion of meat [33][4]. The PLADO does not require adherence to any of these strict diets, but is a flexible LPD of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day range with 50% or more plant-based sources of protein based on the patient’s choice (Table 42). Whereas some nephrologists may promote a pesco-lacto-ovo-vegetarian LPD with >50% plant sources, patients have the ultimate discretion to decide about the non-plant-based portion of the protein ad lib. Based on our decades-old experience in running LPD clinics, most CKD patients will adhere to 50–70% plant-based sources, while some may choose >70% or strictly plant-based diets.

Table 2. Comparing Low Protein Diet (LPD) >50% plant-based protein sources. Known as PLADO, versus standard diet, based on 2400 Cal/day in an 80-kg person.

|

Protein Metric |

Standard Diet |

LPD >50% Plant-based Sources (PLADO) |

|

Proportion of plant-based protein, % |

20–30% |

50–70% * |

|

Total protein per kg IBW, g/kg/day |

>0.8, usually 1.2–1.4 |

0.6–0.8 |

|

Total protein intake, g/day |

96 to 112 g |

48 to 64 g |

|

Protein density, g/100 Cal |

4.4–5.1 |

2.2–2.9 |

|

Proportion of energy from protein, % |

16–19% |

8–11% |

|

Total plant-based protein, g/day |

24–34 |

24–45 |

|

Total animal-based protein, g/day |

68–83 |

14–32 (or none *) |

* up to 100% vegan is allowed based on patient choice.

We recommend a daily sodium intake <3 g/day for a more pragmatic approach [25][22], as opposed to the American Heart Association’s suggested <2.3 g/day given the lack of strong evidence for the latter [25][22]. The PLADO regimen is CKD-patient-centric and flexible with respect to the targeted dietary goals, and is constructed based on the preferences of the patient as opposed to strict dietary regimens, with the dietitian working with patients and their care-partners to that end. Whereas we recommend a moderately low sodium intake of <3 g/day under the PLADO regimen, in those without peripheral edema and well-controlled hypertension, we have allowed slightly higher sodium intake but not greater than 4 g/day given that recent large cohort studies showed poor CKD outcomes with daily urinary sodium excretion >4 g/day [83] (Figure 3)[23].

5. Safety and Adequacy of a Plant-Dominant Low-Protein Diet

Potential challenges of PLADO are outlined in Table 3, which will be largely related to the adequacy and safety of this type of dietary management of CKD patients. The risks of PEW and sarcopenia are the leading concerns, although there is little evidence for these sequelae. As discussed above and based on the U.S. recommended RDA for safe DPI ranges, it is highly unlikely that the targeted DPI of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day with >50% plant sources will engender PEW in clinically stable individuals. No PEW was reported in 16 LPD trials cited above [13,28][1][5], including the MDRD trial [13][1], although PEW per se is a risk of poor CKD outcomes including faster CKD progression [84][24]. However, it is prudent that in patients who may develop signs of PEW or acute kidney injury (AKI), higher DPI targets should be temporarily used until PEW or AKI is resolved. On the other hand, if there is concern related to the likelihood of obesity and hyperglycemia, patients and providers should be reassured that LPD therapy in CKD has not been shown to be associated with such risks, and indeed, an LPD with plant-based sources has salutary effects on insulin resistance and glycemic index, as long as total calorie intake remains within the targeted range of 30–35 kcal/kg/day [34,55][25][26].

Another frequently stated concern is the perceived risk of hyperkalemia. We are not aware of scientific evidence to support the cultural dogma that dietary potassium restriction in CKD improves outcomes [85][27]. Evidence suggests that dietary potassium, particularly from whole, plant-based foods, does not correlate closely with serum potassium variability [86,87][28][29]. Indeed, a high-fiber diet enhances bowel motility and likely prevents higher potassium absorption, and alkalization with plant-based dietary sources also lowers risk of hyperkalemia [88–92][30][31][32][33][34]. Of note, dried-fruit, juices, smoothies, and sauces of fruits and vegetables require additional consideration given their high potassium concentrations. Moreover, newly available potassium-binders, which were not FDA-approved during the era of prior LPD trials such as the MDRD, may be used in the contemporary management of CKD patients at the discretion of clinicians [93][35].

Diet palatability and adherence to LPD or meatless diets are often cited as dietary management challenges. Based on our extensive experience in running patient-centered LPD clinics for hundreds of CKD patients [3][2], and given prior data on dietary adherence research [3,94], the suggested PLADO with DPI of 0.6–0.8 g/kg/day and >50% plant-based sources is feasible and well-accepted among patients with CKD [3][2]. Patients have the opportunity to choose the contribution of protein plant sources between 50% and 75% or >75%, and these two strata along with palatability, appetite [95][36], and adherence should be monitored closely in CKD clinics. If there is concern about inadequate fish intake, given data on the benefits of higher fish intake including fish oil in CKD [96–98][37][38][39], treated CKD patients can be reminded of the opportunity to consume more fish products for their remaining non-plant sources of the dietary protein. Likewise, concerns about B12 deficiency associated with meatless diets can be mitigated by the use of oral supplements as needed [99][40].

References

- Gang Jee Ko; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Jordi Goldstein-Fuchs; Connie M. Rhee; Dietary Approaches in the Management of Diabetic Patients with Kidney Disease. Nutrients 2017, 9, 824, 10.3390/nu9080824.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Linda W Moore; Amanda R. Tortorici; Jason A. Chou; David E. St-Jules; Arianna Aoun; Vanessa Rojas-Bautista; Annelle K. Tschida; Connie M. Rhee; Anuja A. Shah; et al.Susan CrowleyJoseph A. VassalottiCsaba P. Kovesdy North American experience with Low protein diet for Non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease.. BMC Nephrology 2016, 17, 90, 10.1186/s12882-016-0304-9.

- Laetitia Koppe; Denis Fouque; The Role for Protein Restriction in Addition to Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System Inhibitors in the Management of CKD. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 2019, 73, 248-257, 10.1053/j.ajkd.2018.06.016.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Linda W. Moore; Does Kidney Longevity Mean Healthy Vegan Food and Less Meat or Is Any Low-Protein Diet Good Enough?. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 79-81, 10.1053/j.jrn.2019.01.008.

- Connie M. Rhee; Seyed-Foad Ahmadi; Csaba P. Kovesdy; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Low‐protein diet for conservative management of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of controlled trials. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2017, 9, 235-245, 10.1002/jcsm.12264.

- Michael Pignanelli; Chrysi Bogiatzi; G B Gloor; Emma Allen-Vercoe; Gregor Reid; Bradley L. Urquhart; Kelsey N. Ruetz; Thomas J. Velenosi; J. David Spence; Moderate Renal Impairment and Toxic Metabolites Produced by the Intestinal Microbiome: Dietary Implications. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 55-64, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.05.007.

- A M Fogelman; TMAO is both a biomarker and a renal toxin.. Circulation Research 2015, 116, 396-397, 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.114.305680.

- Catherine McFarlane; Christiane I. Ramos; David W. Johnson; Katrina L Campbell; Prebiotic, Probiotic, and Synbiotic Supplementation in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 209-220, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.08.008.

- Ana Paula Black; Juliana S. Anjos; Ludmila Cardozo; Flávia L. Carmo; Carla J. Dolenga; Lia S. Nakao; Dennis De Carvalho Ferreira; Alexandre Soares Rosado; José Carlos Carraro Eduardo; Denise Mafra; et al. Does Low-Protein Diet Influence the Uremic Toxin Serum Levels From the Gut Microbiota in Nondialysis Chronic Kidney Disease Patients?. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, 28, 208-214, 10.1053/j.jrn.2017.11.007.

- Larissa Rodrigues Neto Angéloco; Gabriela Cristina Arces De Souza; Elen Almeida Romão; Paula Garcia Chiarello; Alkaline Diet and Metabolic Acidosis: Practical Approaches to the Nutritional Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, 28, 215-220, 10.1053/j.jrn.2017.10.006.

- Ranjani N Moorthi; Cheryl L. H. Armstrong; Kevin Janda; Kristen Ponsler-Sipes; John R. Asplin; Sharon M. Moe; The effect of a diet containing 70% protein from plants on mineral metabolism and musculoskeletal health in chronic kidney disease.. American Journal of Nephrology 2015, 40, 582-591, 10.1159/000371498.

- Thomas M Campbell; Scott E Liebman; Plant-based dietary approach to stage 3 chronic kidney disease with hyperphosphataemia. BMJ Case Reports 2019, 12, e232080, 10.1136/bcr-2019-232080.

- Marcela T. Watanabe; Pasqual Barretti; Jacqueline Do Socorro Costa Teixeira Caramori; Dietary Intervention in Phosphatemia Control–Nutritional Traffic Light Labeling. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, 28, e45-e47, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.04.005.

- Marcela T. Watanabe; Pasqual Barretti; Jacqueline Do Socorro Costa Teixeira Caramori; Attention to Food Phosphate and Nutrition Labeling. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, 28, e29-e31, 10.1053/j.jrn.2017.12.013.

- Bahar Gürlek Demirci; Emre Tutal; Irem O. Eminsoy; Eyup Kulah; Siren Sezer; Dietary Fiber Intake: Its Relation With Glycation End Products and Arterial Stiffness in End-Stage Renal Disease Patients. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 136-142, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.08.007.

- L Chiavaroli; A Mirrahimi; J L Sievenpiper; D J A Jenkins; P B Darling; Dietary fiber effects in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled feeding trials. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2014, 69, 761-768, 10.1038/ejcn.2014.237.

- Arti Sharma Parpia; Mary L’Abbé; Marc Goldstein; Joanne Arcand; Bernadene Magnuson; Pauline B. Darling; The Impact of Additives on the Phosphorus, Potassium, and Sodium Content of Commonly Consumed Meat, Poultry, and Fish Products Among Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, 28, 83-90, 10.1053/j.jrn.2017.08.013.

- Kelly Picard; Potassium Additives and Bioavailability: Are We Missing Something in Hyperkalemia Management?. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2018, null, null, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.10.003.

- Kristin M. Hirahatake; David R. Jacobs; M D Gross; Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo; Michael G. Shlipak; Holly Mattix-Kramer; Andrew O. Odegaard; The Association of Serum Carotenoids, Tocopherols, and Ascorbic Acid With Rapid Kidney Function Decline: The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) Study. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 65-73, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.05.008.

- Shara Francesca Rapa; Biagio Raffaele Di Iorio; Pietro Campiglia; August Heidland; Stefania Marzocco; Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Chronic Kidney Disease-Potential Therapeutic Role of Minerals, Vitamins and Plant-Derived Metabolites.. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2019, 21, 263, 10.3390/ijms21010263.

- Katherine T. Mills; Jing Chen; Wei Yang; Lawrence J. Appel; John W. Kusek; Arnold Alper; Patrice Delafontaine; Martin G. Keane; Emile Mohler; Akinlolu Ojo; et al.Mahboob RahmanAna C. RicardoElsayed Z. SolimanSusan SteigerwaltRaymond TownsendJiang HeChronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort (CRIC) Study Investigators Sodium Excretion and the Risk of Cardiovascular Disease in Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease.. JAMA 2016, 315, 2200-2210, 10.1001/jama.2016.4447.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Denis Fouque; Nutritional Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 2017, 377, 1765-1776, 10.1056/nejmra1700312.

- Sung Woo Lee; Yong-Soo Kim; Yeong Hoon Kim; Wookyung Chung; Sue K. Park; Kyu Hun Choi; Curie Ahn; Kook-Hwan Oh; Dietary Protein Intake, Protein Energy Wasting, and the Progression of Chronic Kidney Disease: Analysis from the KNOW-CKD Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 121, 10.3390/nu11010121.

- Andrew Morris; Nithya Krishnan; Peter K. Kimani; Deborah Lycett; Effect of Dietary Potassium Restriction on Serum Potassium, Disease Progression, and Mortality in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, null, null, 10.1053/j.jrn.2019.09.009.

- Shivam Joshi; Sanjeev Shah; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Adequacy of Plant-Based Proteins in Chronic Kidney Disease. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2019, 29, 112-117, 10.1053/j.jrn.2018.06.006.

- Shivam Joshi; Sean Hashmi; Sanjeev Shah; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Plant-based diets for prevention and management of chronic kidney disease. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension 2020, 29, 16-21, 10.1097/mnh.0000000000000574.

- Nazanin Noori; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Csaba P. Kovesdy; Rachelle Bross; Debbie Benner; Joel D. Kopple; Association of dietary phosphorus intake and phosphorus to protein ratio with mortality in hemodialysis patients.. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2010, 5, 683-692, 10.2215/CJN.08601209.

- David E. St-Jules; David S. Goldfarb; Mary Ann Sevick; Nutrient Non-equivalence: Does Restricting High-Potassium Plant Foods Help to Prevent Hyperkalemia in Hemodialysis Patients?. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2016, 26, 282-287, 10.1053/j.jrn.2016.02.005.

- Adamasco Cupisti; Claudia D’Alessandro; Loreto Gesualdo; Carmela Cosola; Maurizio Gallieni; Maria Francesca Egidi; Maria Fusaro; Non-Traditional Aspects of Renal Diets: Focus on Fiber, Alkali and Vitamin K1 Intake. Nutrients 2017, 9, 444, 10.3390/nu9050444.

- Pieter Evenepoel; Björn K. Meijers; Dietary fiber and protein: nutritional therapy in chronic kidney disease and beyond.. Kidney International 2012, 81, 227-229, 10.1038/ki.2011.394.

- Hong Xu; Xiaoyan Huang; Ulf Risérus; Vidya M. Krishnamurthy; Tommy Cederholm; Johan Ärnlöv; Bengt Lindholm; Per Sjögren; Juan-Jesus Carrero; Dietary Fiber, Kidney Function, Inflammation, and Mortality Risk. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2014, 9, 2104-2110, 10.2215/CJN.02260314.

- Vidya M. Raj Krishnamurthy; Guo Wei; Bradley C. Baird; Maureen Murtaugh; Michel B. Chonchol; Kalani L. Raphael; Tom Greene; Srinivasan Beddhu; High dietary fiber intake is associated with decreased inflammation and all-cause mortality in patients with chronic kidney disease.. Kidney International 2011, 81, 300-306, 10.1038/ki.2011.355.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; T. Alp Ikizler; Let them eat during dialysis: an overlooked opportunity to improve outcomes in maintenance hemodialysis patients.. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2013, 23, 157-163, 10.1053/j.jrn.2012.11.001.

- Adamasco Cupisti; Csaba P. Kovesdy; C. D'alessandro; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Dietary Approach to Recurrent or Chronic Hyperkalaemia in Patients with Decreased Kidney Function. Nutrients 2018, 10, 261, 10.3390/nu10030261.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Patient education for phosphorus management in chronic kidney disease. Patient Preference and Adherence 2013, 7, 379-390, 10.2147/ppa.s43486.

- Fitsum Guebre-Egziabher; Cyril Debard; Jocelyne Drai; Laure Denis; Sandra Pesenti; Jacques Bienvenu; Hubert Vidal; Martine Laville; Denis Fouque; Differential dose effect of fish oil on inflammation and adipose tissue gene expression in chronic kidney disease patients. Nutrition 2013, 29, 730-736, 10.1016/j.nut.2012.10.011.

- Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; Amy Braglia; Joanne Chow; Osun Kwon; Noriko Kuwae; Sara Colman; David B. Cockram; Joel D. Kopple; An Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Nutritional Supplement for Hypoalbuminemic Hemodialysis Patients: A Pilot/Feasibility Study. Journal of Renal Nutrition 2005, 15, 318-331, 10.1016/j.jrn.2005.04.004.

- Manoch Rattanasompattikul; Miklos Z. Molnar; Martin L. Lee; Ramanath Dukkipati; Rachelle Bross; Jennie Jing; Youngmee Kim; Anne C. Voss; Debbie Benner; Usama Feroze; et al.Iain C. MacDougallJohn A. TayekKeith C. NorrisJoel D. KoppleMark UnruhCsaba P. KovesdyKamyar Kalantar-Zadeh Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Nutrition in Hypoalbuminemic Dialysis Patients (AIONID) study: results of the pilot-feasibility, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Cachexia, Sarcopenia and Muscle 2013, 4, 247-257, 10.1007/s13539-013-0115-9.

- Melissa SooHoo; Seyed-Foad Ahmadi; Hemn Qader; Elani Streja; Yoshitsugu Obi; Hamid Moradi; Connie M. Rhee; Tae Hee Kim; Csaba P. Kovesdy; Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh; et al. Association of serum vitamin B12 and folate with mortality in incident hemodialysis patients.. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2017, 32, 1024-1032, 10.1093/ndt/gfw090.

- Xinmin S. Li; Zeneng Wang; Tomas Cajka; Jennifer A. Buffa; Ina Nemet; Alex G. Hurd; Xiaodong Gu; Sarah M. Skye; Adam B. Roberts; Yuping Wu; et al.Lin LiChristopher J. ShahenMatthew A. WagnerJaana A. HartialaRobert L. KerbyKymberleigh A. RomanoYi HanSlayman ObeidThomas F. LüscherHooman AllayeeFederico E. ReyJoseph A. DiDonatoOliver FiehnW. H. Wilson TangStanley L. Hazen Untargeted metabolomics identifies trimethyllysine, a TMAO-producing nutrient precursor, as a predictor of incident cardiovascular disease risk. JCI Insight 2018, 3, null, 10.1172/jci.insight.99096.