Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Jesús L. Yániz and Version 2 by Vivi Li.

The quality of honey bee drone semen is relevant in different contexts, ranging from colony productivity to pathology, toxicology and biodiversity preservation. Despite its importance, considerably less knowledge is available on this subject for the honey bee when compared to other domestic animal species. A proper assessment of sperm quality requires a multiple testing approach which discriminates between the different aspects of sperm integrity and functionality. Most studies on drone semen quality have only assessed a few parameters, such as sperm volume, sperm concentration and/or sperm plasma membrane integrity.

- Apis mellifera

- male

- reproduction

- semen

- sperm quality

1. Introduction

Honey bees are one of the most important pollinators, playing a vital role in plant pollination of crop and wild species. For instance, it has been estimated that approximately 70% of all crop species worldwide are dependent on bees for pollination [1]. However, recent reports of high colony losses worldwide have raised public concern for the future of honeybees [2][3][2,3]. Regardless of the underlying causes of these losses, with many factors possibly involved [4], efficient reproduction is fundamental for replacing dead colonies.

A limiting factor of successful reproduction may be sperm quality. Since the queen will store viable sperm after insemination for several years, the study of semen quality in this species is especially relevant. It may determine the reproductive success of the queen and, as a consequence, the colony’s survival and level of productivity [5], as well as the success of artificial insemination (AI, also called instrumental insemination in this species) [6][7][6,7]. Poor semen quality generates poorer quality queens, this being considered one of the main causes of colony loss [8]. The study of drone sperm quality is also of considerable research interest. To date, it has been applied to study the effects of age [9][10][11][12][9,10,11,12], body size [13], genetics [10][12][10,12], temperature [11][14][11,14], nutrition [11], management [15][16][15,16], seasonal variations [10][17][10,17], disease [18][19][18,19], insecticides [20][21][20,21], miticides [22], semen storage in liquid and frozen states [9][23][24][25][26][9,23,24,25,26], semen handling [9][27][28][9,27,28], sperm competition [29] and physiology [30].

2. Normal Sperm Structure in the Honey Bee

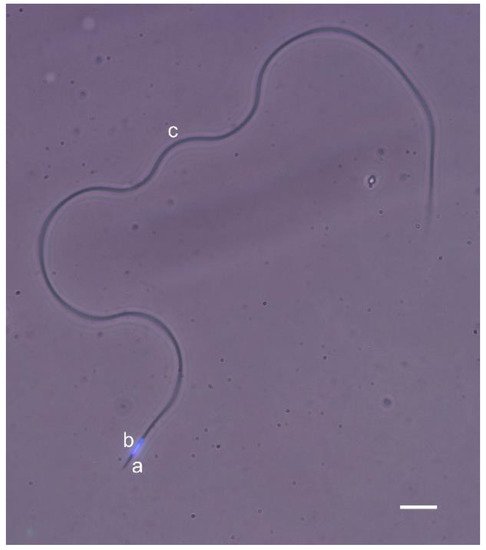

Honey bee sperm are long and filamentous cells with tapered ends (Figure 1) [31][32][33][31,32,33]. With a length of 250–270 µm and a width of 0.7 µm, the sperm consists of a relatively small and narrow head region (10 µm long and 0.4–0.5 µm in width [33]), the transitional centriole adjunct and the flagellum. The sperm head contains two consecutive parts of equal size: the acrosomal complex followed by a linear nucleus. The acrosomal complex is formed by a conical and two-layered acrosomal vesicle that covers the perforatorium up to the anterior nuclear end, where the perforatorium is inserted into a deep fossa [31]. The nucleus is dense and elongated, with a compact chromatin. The sperm flagellum is formed by an axoneme of 9+9+2 microtubular pattern, two large mitochondrial derivatives and two accessory bodies. The mitochondrial derivatives are asymmetrical in length and diameter and lie parallel to the axoneme throughout the sperm flagellum. The two accessory bodies are elongated structures located between the axoneme and each mitochondrial derivative.

Figure 1. A combined phase-contrast and fluorescence (Hoechst) image of a honey bee spermatozoon showing the acrosome (a), nucleus (b) and flagellum (c). Scale-bar = 10 µm.

3. Sperm Life Cycle in the Honey Bee

3.1. Spermatogenesis and Sperm Storage in the Male

Spermatozoa are produced in the drone testes from the larval to the pupal stages of development [34][35][34,35]. Between days 3 and 8 after emergence, the spermatozoa are transported from the testes to the seminal vesicles [34][36][37][34,36,37], where they are stored until ejaculation [37]. Immediately after emergence from their cells, drones are unable to copulate for about 9–12 days. However, there may be great variation in the time drones take to reach sexual maturity, which can depend on their genetics and the quality of the colony in which they are reared [10][16][10,16].

3.2. Mating, Sperm Storage in the Spermatheca and Egg Fertilization

Mating is the most significant function of an adult drone, although most of them fail in this task. Drones mate with the queen during the mating flight at the age of 15–23 days, 21 days on average [38]. In the afternoon of days with good weather [39][40][39,40], drones fly from the colonies to the male congregation areas, with a diameter of around 30–200 m, where thousands of drones from hundreds of colonies may await the arrival of a few virgin queens [41]. When a queen approaches a male congregation area, the drones chase her trying to copulate, forming a comet-like swarm in her wake. Normally, the queen mates consecutively with several drones in rapid sequence during the mating (nuptial) flight [10]. Earliest studies suggested that the queens copulate with 12–14 drones on average, usually in one or two mating flights [42][43][44][45][42,43,44,45], but a recent study suggested that the degree of polyandry might be much higher, so that queens can mate up to 34–77 males [46]. During mating, 6–12 million spermatozoa are transferred from the seminal vesicles of the drone into the genital orifice of the queen through the drone’s irreversibly everted endophallus [10]. After ejaculation, the endophallus is broken off inside the queen, acting as a temporary vaginal plug that may prevent sperm leakage, and the drone dies shortly afterwards. Approximately 10% of each male’s ejaculate is transferred to the queen’s oviducts [47] where the semen of the different drones is mixed [48].

After the nuptial flight, the queen returns to the hive, where the process of sperm transport from the oviducts to the spermatheca can take up to 40 h. Finally, only 3–5% of the received spermatozoa, 2 to 7 million, are usually stored [43][49][50][43,49,50], with an average of around 4–5 million sperm [51][52][51,52]. The queens do not mate again after the onset of oviposition [42], so that this sperm quantity must be enough to fertilize million eggs over their entire life span [53]. In the latter study it was also demonstrated that only two spermatozoa are required on average for egg fertilization.