Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Amina Yu and Version 1 by Piero Fariselli.

Predicting protein stability changes upon genetic variations is still an open challenge. It is essential to understand the impact of the alterations in the amino acid sequence, mainly due to non-synonymous (or missense) DNA variations leading to the disruption or the enhancement of the protein activity, on human health and disease [1,2,3,4]. In particular, protein stability perturbations have already been associated to pathogenic missense variants [5] and they were shown to contribute to the loss of function in haploinsufficient genes [6].

- deep learning

- protein stability

- free energy changes

- antisymmetry

- ACDC

- sequence

1. Introduction

The protein stability changes upon variations of the amino acid sequence is usually expressed as the Gibbs free energy of unfolding ( ), which is defined as the difference between the energy of the mutated structure of the protein and its wild-type form ( ). Thermodynamics imposes an antisymmetry relationship on that can be summarized as follows: given the wild-type (W) and mutated (M) protein structures, differing by one residue in position X, the quantity represents the change in the protein stability caused by the amino acid substitution . Similarly, given the symmetry between the two molecular systems M and W, for the reverse variation the corresponding change in Gibbs free energy has the opposite sign:

Since experimental measurement of is a time-consuming and complex task, during the last decades several computational tools have been developed to predict values. Some methods are structure-based, requiring the knowledge of the protein tertiary structure [7,8,9,10,11,12], others are sequence-based, either relying only on protein sequences [13,14,15] or optionally taking advantage of the protein structure when available [16,17]. However, most of these methods violate the antisymmetry property and suffer from high biases in predicting reverse variations [10,18,19,20,21,22,23]. To address this problem we recently introduced ACDC-NN, a novel structure-based method that satisfies the physical property of antisymmetry, while reaching comparable performance to the state-of-the-art methods [24]. However, the experimental structure determination and characterization of protein thermodynamical features are still limited [18], while a dramatic increase in protein sequence databases has occurred as genomic and metagenomic sequencing efforts have expanded in the last years. The latest release of UniProtKB/TrEMBL protein database contains 214,406,399 sequence entries in all, including 175,817 human proteins, while the Protein Data Bank contains 177,655 entries, 52,485 of them human. Hence, computational approaches able to predict the impact of genetic variations on the protein stability using only sequence information are needed. To this aim, we created ACDC-NN-Seq, a sequence-based version of ACDC-NN that, like its predecessor, achieves accurate predictions satisfying the antisymmetry property, without the need for tertiary protein structures. Here we show that ACDC-NN-Seq compares well with both sequence-based and structure-based methods. We tested the antisymmetry of the predictions on an unbiased dataset and the accuracy on three clinically relevant proteins, avoiding overfitting by filtering out sequence similarities greater than 25%.

2. Learning 3D Properties on Artificial Data

A proper training of a neural network requires a huge amount of experimental values that are not currently available; we addressed this problem by performing a pre-training phase on the artificial dataset IvankovDDGun and then applying a transfer learning on the experimental datasets S2648 and Varibench, as described in the Materials and Methods section.

In Table 3Table 1, we show the results on the IvankovDDGun test set. It is worth noticing that the DDGun3D values were computed using the protein structures, while the ACDC-NN-Seq predictions are only based on sequence information. Thus, this approach obtained a sequence-based method capable of internally encoding the 3D statistical potentials that maintain the antisymmetric property.

Table 31. Results on the IvankovDDGun test set: The performance of ACDC-NN-Seq in learning DDGun3D was measured in terms of Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and root mean square error (RMSE). The antisymmetry property was assessed in terms of Pearson correlation coefficient ( ) and the bias ( ) between the predicted values. RMSE and are expressed in kcal/mol. IvankovDDGun (Test) is the test set extracted from the IvankovDDGun artificial dataset.

| Dataset | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | |||

| IvankovDDGun (Test) | 0.97/0.06 | 0.97/0.06 | −1.0 | 0.0 |

3. Prediction of the Experimental Values

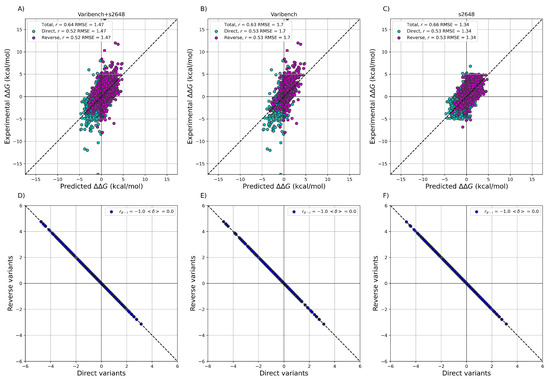

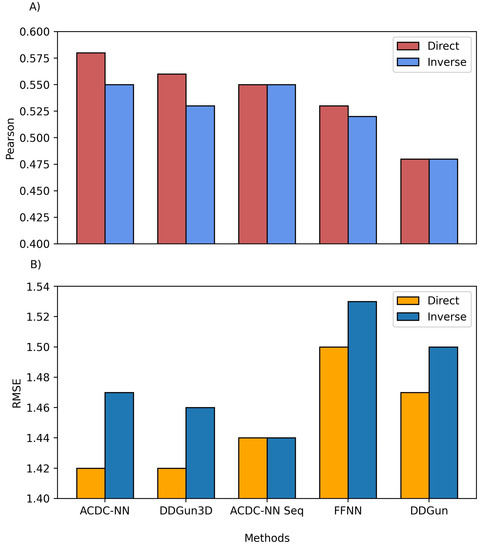

After training ACDC-NN-Seq on the IvankovDDGun set, we fine-tuned the network by retraining the last layers on the experimentally-derived values from S2648 and Varibench through 10-fold cross-validation. In Figure 3 Figure 1 we showed the experimental values versus the ACDC-NN-Seq predicted ones on Varibench and S2648 datasets both combined and alone, and for both direct and reverse variations. These results were obtained in cross-validation as explained in Benevenuta et al. . ADCD-NN-Seq achieved both consistent performance with the state-of-the-art methods (measured in terms of r and ) and perfect antisymmetry ( and ).

Figure 31. Performance of ACDC-NN-Seq on predicting for the direct and reverse variations on: (A) Varibench and S2648 ( , kcal/mol); (B) Varibench alone ( , kcal/mol); (C) S2648 alone ( , kcal/mol). Direct versus reverse values of (D) Varibench and S2648 variations, (E) Varibench variations alone, (F) S2648 variations alone, predicted by ACDC-NN-Seq, with a Pearson correlation of and kcal/mol for all three datasets. All the predictions reported in this figure were obtained through a 10-fold cross-validation with sequence identity <25% among all folds.

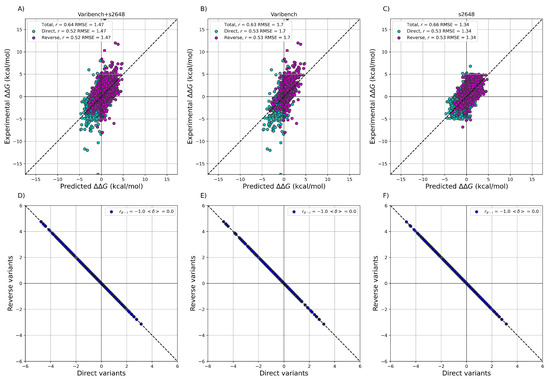

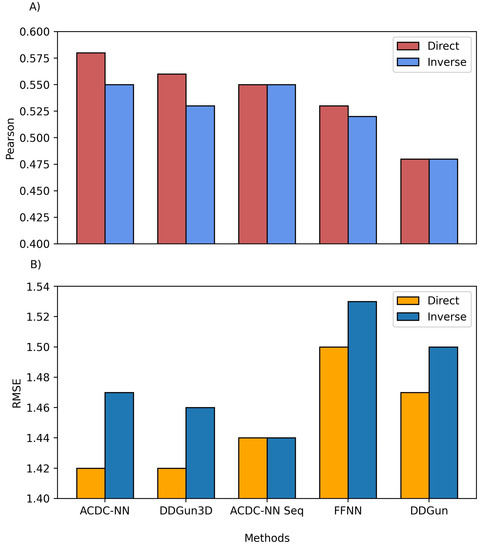

We also compared the predictions of both ACDC-NN-Seq and DDGun with their corresponding stucture-based versions, i.e., ACDC-NN and DDGun3D. Figure 4 Figure 2 reports the comparison performance (in cross-validation for ACDC-NN and ACDC-NN-Seq) on the Ssym dataset , which was specifically built to assess the antisymmetry and it contains experimental values for direct and reverse variants. The performance of ACDC-NN-Seq is balanced and close to those obtained using the protein structures. This makes ADCD-NN-Seq ideal for genome variant analyses.

Figure 42. Comparison between the structure and sequence-based versions of ACDC-NN, DDGun and a Feed-Forward Neural Network (FFNN) on the Ssym dataset. (A) Pearson correlation coefficient (r), where higher is better and (B) root mean squared error (RMSE), where lower is better.

In order to evaluate the effect of the neural network design, we compared ACDC-NN-Seq with a feed-forward neural network (FFNN) trained and optimized in the same conditions. The structure of the optimized FFNN consists of an input layer of 140 input neurons (window of 7 residues coded with 20-element vector profiles), a sequence of hidden layers consisting of (128,64,32,16) neurons, and an output neuron coding for the value. Thus the main difference is due to the anty-symmetric construction of ACDC-NN-Seq (FFNN Figure 4Figure 2). FFNN performance is quite good, and the neural networks learned most of the antisymmetry from the data provided (direct and reverse variations). However, ACDC-NN-Seq outperforms FFNN both in the prediction task and antisymmetry reconstructions.

Regarding the results presented in Figure 3 Figure 1 and Figure 4Figure 2, it is worth noticing that the maximum achievable Pearson’s correlation is not necessarily equal to 1, as usually thought. It may be far lower depending on the experimental uncertainty and the distributions . In particular, when considering the different experiments on the same variants included in the Protherm database or in manually-cleaned datasets, the expected Pearson upper bound is in the range of 0.70–0.85 . Significantly higher Pearson correlations can be obtained in small sets or might be indicative of overfitting issues .

4. Comparison with Other Sequence-Based Machine-Learning Methods

As mentioned above, few available methods can predict the effect of the variants on the protein stability starting from sequence only. We therefore compared ACDC-NN-Seq on three datasets with the following sequence-based methods: DDGun , INPS , I-Mutant2.0 , MUpro and the recent SAAFEC-SEQ .

The obtained results are reported in Table 4Table 2; ACDC-NN-Seq predicts equally well both direct and reverse variants with nearly perfect antisymmetry ( ). ACDC-NN-Seq performance is higher than the one obtained by INPS, which is the only machine-learning method proven to be antisymmetric in past tests .

. Results on p53: Comparison on p53. The INPS, SAAFEC-SEQ and I-mutant2.0 results were obtained using their stand alone code, those of MUpro were obtained using the webserver available.

Table 42. Results on Ssym: The performance on both direct and reverse variants was measured in terms of Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and root mean square error (RMSE). The antisymmetry was assessed using the correlation coefficient (2) and the bias (3). RMSE and are expressed in kcal/mol. The results of INPS were taken from Montanucci et al. and Fariselli et al. ; the results of SAAFEC-SEQ and I-mutant2.0 were obtained using their stand-alone code, those of MUpro were obtained using the webserver available. Only Inps-NoSeqId and ACDN-NN-Seq were trained in cross-validation addressing the sequence identity issue (sequence similarity <25%).

| Method | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | |||

| Method | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | |||

| 0.04/2.87 | ||||

| 0.12 | ||||

| −0.98 | ||||

Table 65. Results on p53: Comparison on p53. The INPS, SAAFEC-SEQ and I-mutant2.0 results were obtained using their stand alone code, those of MUpro were obtained using the webserver available.

| Method | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | |||

| Direct | Reverse | |||

Table 76. Results on Frataxin Challenge in CAGI5 . The INPS, SAAFEC-SEQ and I-mutant2.0 results were obtained using their stand alone code, those of MUpro were obtained using the webserver available.

| Method | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Reverse | |||||||||||||

| ACDC-NN-Seq | 0.55/1.44 | ACDC-NN-Seq0.55/1.44 | 0.56/0.97 | |||||||||||

| ACDC-NN-Seq | 0.62/1.62 | −0.99 | −0.01 | |||||||||||

| 0.56/0.97 | INPS-NoSeqId | |||||||||||||

| ACDC-NN-Seq | 0.62/1.62 | 0.62/1.62 | −1.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.48/1.42 | ||||||||||||

| 0.62/1.62 | −1.00 | 0.00 | 0.47/1.45 | −0.99 | ||||||||||

| ACDC-NN-Seq | 0.88/2.83 | 0.88/2.83 | −1.00 | 0.00 | ||||||||||

| −0.06 | ||||||||||||||

| INPS | 0.60/0.99 | |||||||||||||

| INPS | 0.61/0.98 | −1.00 | 0.01 | INPS | ||||||||||

| INPS | 0.72/1.49 | 0.51/1.42 | ||||||||||||

| 0.70/1.54 | −0.99 | −0.01 | ||||||||||||

| 0.72/1.49 | 0.70/1.54 | −0.99 | 0.65/3.29 | −0.01 | 0.57/3.38 | −0.99 | −0.01 | INPS | SAAFEC-SEQ | SAAFEC-SEQ0.50/1.44 | −0.99 | −0.04 | ||

| 0.63/0.89 | 0.30/1.63 | −0.21 | −1.50 | 0.52/1.64 | −0.18/2.97 | |||||||||

| SAAFEC-SEQ | 0.52/1.64 | 0.06 | −1.79 | |||||||||||

| −0.18/2.97 | 0.06 | −1.79 | ||||||||||||

| SAAFEC-SEQ | 0.67/3.3 | 0.1/4.85 | 0.2 | −1.94 | SAAFEC-SEQ | 0.71/1.09 | −0.39/2.71 | 0.58 | −1.84 | |||||

| I-Mutant2.0 | I-Mutant2.00.56/1.12 | 0.39/1.71 | −0.45 | −0.88 | I-Mutant2.0 | 0.35/1.75 | 0.22/2.81 | −0.24 | −1.02 | I-Mutant2.0 | 0.7/1.12 | 0.05/2.54 | −0.17 | −1.01 |

| MUpro | 0.79/0.94 | 0.07/2.51 | −0.02 | −0.97 | ||||||||||

I-Mutant2.0 and MUpro do not respect the antisymmetry property since this issue was not properly addressed or known at the time the two models were created. However, it must be noted that both I-Mutant2.0 and MUpro do not use evolutionary information making them extremely fast predictors, as compared to ACDC-NN-Seq, which requires a multiple sequence alignment.

Another significant point is that, looking at all the methods reported in Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6Table 4, only Inps-NoSeqId and all the versions of ACDN-NN were trained in cross-validation removing the sequence identity (i.e., sequence similarity <25%).

Table 53. Results on myoglobin: Comparison on myoglobin. The INPS, SAAFEC-SEQ and I-mutant2.0 results were obtained using their stand alone code, those of MUpro were obtained using the webserver available.

| Method | Pearson/RMSE | Antisymmetry | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.35/1.75 | ||||

| 0.22/2.81 | ||||

| MUpro | 0.51/0.99 | 0.35/1.75 | −0.17 | −0.79 |

Table 64

| −0.24 | |||||

| −1.02 | |||||

| I-Mutant2.0 | 0.84/2.82 | 0.53/5.08 | −0.74 | −1.22 | MUpro |

| MUpro | 0.23/1.78 | 0.23/1.78 | 0.04/2.87 | ||

| MUpro | 0.33/3.6 | 0.13/4.97 | 0.12 | −0.98 |

5. Frataxin CAGI 5 Challenge

The Critical Assessment of Genome Interpretation (CAGI) is a community experiment aimed at fairly assessing the computational methods for genome interpretation . In CAGI 5, data providers measured unfolding free energy of a set of variants with far-UV circular dichroism and intrinsic fluorescence spectra on Frataxin (FXN), a highly conserved protein fundamental for the cellular iron homeostasis in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. These measurements were used to calculate the change in unfolding free energy between the variant and wild-type proteins at zero denaturant concentrations ( ). In addition, the experimental dataset , including eight amino acid substitutions, was used to evaluate the performance of the web-only tools, based on protein structure information, for predicting the value of the associated . Here we compare the available machine-learning sequence-based predictors on the dataset (Table 7Table 6), showing the consistency of the prediction performance of ACDC-NN-Seq.

| −0.23 |

| −0.45 |

References

- Schymkowitz, J.; Borg, J.; Stricher, F.; Nys, R.; Rousseau, F.; Serrano, L. The FoldX web server: An online force field. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W382–W388.

- Wainreb, G.; Wolf, L.; Ashkenazy, H.; Dehouck, Y.; Ben-Tal, N. Protein stability: A single recorded mutation aids in predicting the effects of other mutations in the same amino acid site. Bioinformatics 2011, 27, 3286–3292.

- Parthiban, V.; Gromiha, M.M.; Schomburg, D. CUPSAT: Prediction of protein stability upon point mutations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, W239–W242.

- Pucci, F.; Bernaerts, K.V.; Kwasigroch, J.M.; Rooman, M. Quantification of biases in predictions of protein stability changes upon mutations. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3659–3665.

- Li, B.; Yang, Y.T.; Capra, J.A.; Gerstein, M.B. Predicting changes in protein thermodynamic stability upon point mutation with deep 3D convolutional neural networks. PLOS Comput. Biol. 2020, 16, e1008291.

- Kellogg, E.H.; Leaver-Fay, A.; Baker, D. Role of conformational sampling in computing mutation-induced changes in protein structure and stability. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2011, 79, 830–838.

- Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P.L.; Savojardo, C.; Casadio, R. INPS: Predicting the impact of non-synonymous variations on protein stability from sequence. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 2816–2821.

- Montanucci, L.; Capriotti, E.; Frank, Y.; Ben-Tal, N.; Fariselli, P. DDGun: An untrained method for the prediction of protein stability changes upon single and multiple point variations. BMC Bioinform. 2019, 20, 335.

- Li, G.; Panday, S.K.; Alexov, E. SAAFEC-SEQ: A Sequence-Based Method for Predicting the Effect of Single Point Mutations on Protein Thermodynamic Stability. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 606.

- Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P.; Casadio, R. I-Mutant2. 0: Predicting stability changes upon mutation from the protein sequence or structure. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, W306–W310.

- Cheng, J.; Randall, A.; Baldi, P. Prediction of protein stability changes for single-site mutations using support vector machines. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinform. 2006, 62, 1125–1132.

- Sanavia, T.; Birolo, G.; Montanucci, L.; Turina, P.; Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P. Limitations and challenges in protein stability prediction upon genome variations: Towards future applications in precision medicine. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020.

- Savojardo, C.; Fariselli, P.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R. INPS-MD: A web server to predict stability of protein variants from sequence and structure. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2542–2544.

- Fang, J. A critical review of five machine learning-based algorithms for predicting protein stability changes upon mutation. Brief. Bioinform. 2020, 21, 1285–1292.

- Usmanova, D.R.; Bogatyreva, N.S.; Ariño Bernad, J.; Eremina, A.A.; Gorshkova, A.A.; Kanevskiy, G.M.; Lonishin, L.R.; Meister, A.V.; Yakupova, A.G.; Kondrashov, F.A.; et al. Self-consistency test reveals systematic bias in programs for prediction change of stability upon mutation. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, 3653–3658.

- Montanucci, L.; Savojardo, C.; Martelli, P.L.; Casadio, R.; Fariselli, P. On the biases in predictions of protein stability changes upon variations: The INPS test case. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2525–2527.

- Capriotti, E.; Fariselli, P.; Rossi, I.; Casadio, R. A three-state prediction of single point mutations on protein stability changes. BMC Bioinform. 2008, 9, 1–9.

- Benevenuta, S.; Pancotti, C.; Fariselli, P.; Birolo, G.; Sanavia, T. An antisymmetric neural network to predict free energy changes in protein variants. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 245403.

More