Ankyrin-B (encoded by ANK2), originally identified as a key cytoskeletal-associated protein in the brain, is highly expressed in the heart and plays critical roles in cardiac physiology and cell biology. In the heart, ankyrin-B directs the targeting and localization of key ion channels and transporters, structural proteins, and signaling molecules. The role of ankyrin-B in normal cardiac function is illustrated in animal models lacking ankyrin-B expression, which display significant electrical and structural phenotypes,1 and life-threatening arrhythmias. Further, ankyrin-B dysfunction has been associated with cardiac phenotypes in humans (now referred to as “ankyrin-B syndrome”) including sinus node dysfunction, heart rate variability, atrial fibrillation, conduction block, arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy, structural remodeling, and sudden cardiac death.

1. Introduction: Ankyrin Proteins

The ankyrin family of polypeptides was first identified in the erythrocyte plasma membrane in 1979 by Bennett and Stenbuck

[1]. Following this discovery, ankyrin was discovered in various organs and cell types, including brain

[2,3,4][2][3][4] and myogenic cells

[5,6][5][6]. We now know that ankyrins are derived from three ankyrin genes:

ANK1, ANK2, and

ANK3 [7,8,9][7][8][9].

ANK1 encodes ankyrin-R (AnkR),

ANK2 encodes ankyrin-B (AnkB), and

ANK3 encodes ankyrin-G (AnkG) ().

Table 1. Brief summary of ankyrin family proteins: ankyrin-R, ankyrin-B, ankyrin-G.

| |

Ankyrin-R |

Ankyrin-B |

Ankyrin-G |

| Tissue Expression |

erythrocytes [1], myelinated axons [10], striated muscle [11] |

ubiquitously expressed, cardiomyocytes (T-tubules, SR, plasma membrane) [12], neurons [8] |

ubiquitously expressed, neurons (AIS, and nodes of Ranvier) [13], cardiomyocytes (intercalated disc) [14] |

| Examples of Binding Partners |

CD44 [15], NKA [16], Rh type A glycoprotein [17], obscurin [11] |

PP2A [12,13][12][13], NCX [12], NKA [18], Kir6.2 [12,13][12][13], CaV1.3 [19], βII-spectrin [20] |

NaV1.6, βIV-spectrin, L1CAMs [1,21,22][1][21][22], plakophilin-2 [23] NaV1.5 [14] |

| Isoforms |

sAnk1.5, 1.6, 1.7, and 1.9 [11] |

AnkB-188 and AnkB-212 [24]. Giant AnkB (440-kD) |

Giant AnkG (480-kD) [25] |

| Disease associated with variants |

hereditary spherocytosis [26] |

Ankyrin B syndrome: SCD, SND, AF, LQTS, VT, bradycardia, syncope [12], ARVC [27] |

Brugada syndrome [12], dilated cardiomyopathy [28], cognitive disabilities [29] |

Ankyrin-R is primarily expressed in erythrocytes and was the first ankyrin identified as an adaptor protein

[1], linking erythrocyte membrane proteins to the actin-based cytoskeleton

[30]. AnkR is important for the structural integrity and organization of the erythrocyte membrane. Moreover, loss-of-function variants in human

ANK1 have been linked to ~50% of hereditary spherocytosis cases

[31], a complex form of hemolytic anemia that affects 1:2000 people of Northern European descent

[26] and results from a loss of membrane surface tension in red blood cells

[32]. AnkR regulates erythrocyte membrane expression of CD44

[15], Na

+/K

+ ATPase (NKA)

[16], and the Rh type A glycoprotein

[17]. Although AnkR is primarily expressed in erythrocytes, AnkR is also expressed in myelinated axons

[10].

ANK1 also encodes four small ankyrin-1 isoforms (sAnk1.5, 1.6, 1.7, and 1.9) that are highly expressed in striated muscle. These isoforms bind obscurin and stabilize the sarcoplasmic reticulum in striated muscle

[11].

Ankyrin-B was first identified in the brain

[8] and has since been identified as a critical adaptor and scaffolding protein in the heart, that mediates the interaction of integral membrane proteins with the spectrin-actin cytoskeletal network

[13,33][13][33].

ANK2 encodes multiple isoforms that may contribute to disease. AnkB will be reviewed in detail below.

Ankyrin-G plays an important role across multiple excitable tissues. In the brain, AnkG links integral membrane proteins with the actin/spectrin-based membrane skeleton at axon initial segments (AIS) including Na

V1.6, βIV spectrin, and L1CAMs

[21,22,33][21][22][33]. In the heart, AnkG is required for localization of Na

V1.5 and CaMKII to the cardiomyocyte intercalated disc

[13,14,34][13][14][34]. In mice selectively lacking AnkG expression in cardiomyocytes, βIV-spectrin and Na

V1.5 expression and localization are disrupted, and voltage-gated Na

V channel activity (I

Na) is significantly decreased. These animals experience a reduction in heart rate, impaired atrioventricular conduction, increased PR intervals, and increased QRS intervals

[14]. Further, AnkG cKO mice display arrhythmias in response to adrenergic stimulation. In humans, an

SCN5A variant in the AnkG-binding motif of Na

V1.5 has been associated with Brugada syndrome and arrhythmia

[12]. This same variant is a loss-of-function variant when expressed in primary cardiomyocytes. Similar to other ankyrin genes,

ANK3 encodes multiple isoforms of AnkG. Giant AnkG is a 480-kD protein required for proper AIS and node of Ranvier assembly due to the clustering of Na

V channels

[35]. Human variants affecting 480-kD AnkG are associated with severe cognitive disability

[29]. The role of Giant AnkG isoforms in the heart is currently unknown and is an important area for future research.

AnkB and AnkG are ubiquitously expressed, but their functions are distinct. Although AnkG plays a crucial role in the brain, variants in AnkG have been connected to Brugada syndrome

[12] and, more recently, dilated cardiomyopathy

[28]. Although AnkB and AnkG have similar structures, AnkG partners with proteins at the intercalated disc, including plakophilin-2

[23] and Na

V1.5

[14], while AnkB is crucial for the expression and localization of ion channels at the sarcoplasmic reticulum, transverse-tubules, and plasma membrane

[12]. However, Roberts et al. recently identified small populations of AnkB at the intercalated disc

[27]. Cardiomyocytes from mice heterozygous for a null mutation in ankyrin-B display mislocalization and a decrease in expression of Na

+/Ca

2+ exchanger (NCX) and Na

+/K

+-ATPase (NKA)

[36]. Further, Roberts et al. demonstrated that β-catenin is a novel AnkB-binding partner, where β-catenin localization is disrupted in individuals with

ANK2 variants who presented with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

[27]. Importantly, ankyrins -G and -B retain non-overlapping, non-compensatory functions despite their similarity in sequence. Distinct from AnkG-associated disease, variants in AnkB are tied to a specific set of clinical phenotypes, including susceptibilities to sinus node dysfunction and acquired heart diseases such as atrial fibrillation

[12] and heart failure

[37]. Ankyrin specificity, at least in part, is attributed to an autoinhibitory linker peptide between the membrane-binding domain (MBD) and spectrin-binding domain (SBD), which prevents AnkB from binding with protein partners

[38]. Further specificity is attributed to key roles of the divergent C-terminal domains of AnkB and AnkG. Additional mechanisms underlying ankyrin specificity in vivo are a key area for future research.

2. Ankyrin-B Structure and Binding Partners

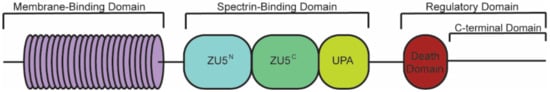

Canonical ankyrin proteins share a similar structure composed of an MBD, SBD, and a regulatory domain (RD) that is comprised of a death domain (DD) and C-terminal domain (CTD) (). The MBD of AnkB is divided into four subdomains composed of 24

ANK repeats, which are defined by their repeated alpha-helical structure

[43][39].

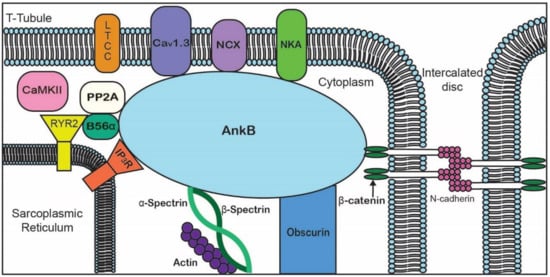

ANK repeats are not specific to the three canonical ankyrin proteins and are present across a range of functionally diverse proteins including SHANK, BARD1, and ANKRD. The AnkB MBD regulates the localization of ion channels and transporters ( and ).

Figure 1. Structure of canonical ankyrin-B. Canonical ankyrin proteins share four domains: a membrane-binding domain (MBD), spectrin-binding domain (SBD), death domain (DD), and C-terminal domain (CTD). The MBD consists of 24 ANK repeats that are defined by their secondary structure and aid in protein folding regulation. The SBD consists of ZU5N, ZU5C, and UPA domains that are important for binding βII-spectrin and supporting cardiomyocyte structure. The DD and CTD comprise the regulatory domain.

Figure 2. Representative diagram of ankyrin-B-binding partners to emphasize the importance of AnkB in the localization of ion channels, transporters, pumps, and structural proteins for proper cardiomyocyte function.

Table 2. Ankyrin-B-binding partners in the heart.

| Membrane-Binding Domain |

Spectrin-Binding Domain |

Regulatory Domain |

| Ion channels |

Transporters/Pumps |

β-spectrin |

HSP40 |

| IP3R |

Anion Exchanger |

PP2A |

Obscurin |

| Cav1.3 |

Na/Ca Exchanger |

|

Ankyrin MBD |

| Kir6.2 |

Na/K ATPase |

|

| Structural |

Cell adhesion |

|

|

| Tubulin β-catenin |

L1CAMs |

| |

β-dystroglycan |

| |

Dystrophin |

3. Ankyrin-B Variants in Cardiovascular Disease

AnkB variants have been identified in all four domains of the AnkB protein and are linked to a spectrum of cardiovascular phenotypes. AnkB is classically associated with human arrhythmia syndromes, many of which demonstrate incomplete penetrance and variable expressivity

[12,50,51,52][12][46][47][48]. In fact, it is likely that secondary genetic, lifestyle, and/or environmental factors are necessary to cause disease. Ankyrin-B syndrome, originally classified as long QT syndrome type 4, is a heritable arrhythmogenic disease that is the result of loss-of-function mutations in

ANK2. A p.E1425G variant was discovered in a French family suffering from sinus bradycardia, atrial fibrillation, and sudden cardiac death and was the first to be implicated in AnkB syndrome

[12,53][12][49].

Although the p.E1425G variant is localized to the AnkB regulatory domain, loss-of-function variants in all four ankyrin domains are now associated with AnkB syndrome

[12,54][12][50]. Notably, these variants show a range of clinical severity and phenotypes, including torsades de pointes (TdP), ventricular tachycardia, and long QT syndrome, a variability that is reflected at the cellular level

[12]. This inconsistency of phenotype puts into the question the mechanics behind AnkB-associated diseases that have yet to be fully elucidated. Although the AnkB MBD is imperative for AnkB interactions and function within the heart, the first disease-associated loss-of-function variant in this domain, p.S646F, was only recently identified within the First Nations of Northern British Columbia

[54][50]. Individuals with this variant also exhibited congenital heart defects, Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, and cardiomyopathy. These compounded symptoms are the result of improper NCX localization, subsequent Ca

2+ overload, and possible disruption of pacemaking activity

[12,36][12][36].

Variants within the SBD pose distinct mechanisms of disease. Several AnkB variants including the p.R990Q

[20], p.A1000P, and p.DAR976AAA are present within the highly conserved ZU5

N region of the SBD that directly binds βII-spectrin, disrupting this interaction. Importantly, AnkB co-immunoprecipitates with a larger complex composed of βII-spectrin, NKA, and NCX

[20]. Although p.A1000P and p.DAR976AAA demonstrated normal AnkB activity with altered βII-spectrin binding, the p.R990Q variant showed altered AnkB functionality, including an inability to rescue NCX localization in AnkB knockout myocytes and severe arrhythmia attributed to disruption of the AnkB-spectrin interaction

[20]. Notably, the p.Q1283H variant within the ZU5

C region disrupts PP2A activity via loss of B56α targeting, which increases RyR2 phosphorylation and disrupts the calcium dynamics associated with excitation-contraction (EC) coupling

[45][41]. Notably, alterations in RyR2 activity are associated with dilated cardiomyopathy and offer an additional area for future investigation.

Variants in

ANK2 have also been associated with sinus node disease (SND)

[12] and most recently with arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy (ACM)

[27]. In fact, the p.E1425G variant segregated with sinus node disease with nearly complete penetrance

[45][41]. Similar to

ANK2 loss of function mutations,

ANK2 transection in chromosome 4, leading to

ANK2 haploinsufficiency, was associated with ankyrin-B syndrome

[55][51].

Although AnkB is commonly associated with arrhythmias, variants in

ANK2 have also been associated with structural heart disease. Lopes et al. found that individuals with

ANK2 variants had a greater maximum wall thickness in the left ventricle, in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

[50][46]. AnkB has also been linked to acquired heart disease and tissue remodeling following infarct in canine animal models

[12]. Following coronary artery occlusion, AnkB mRNA and protein levels decrease in the cardiomyocytes found at the infarct border zone (BZ), as do common AnkB-binding partners including NCX and NKA. These findings provide new insight into the role of AnkB in heart failure and possibly for the cardiac remodeling that supports the creation of arrhythmogenic substrates at the border zone

[37].

Recently,

ANK2 variants have been identified in individuals with arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

[27], a disease characterized by a severe structural and electrical cardiac phenotype that involves the fibrofatty replacement of healthy myocardium, malignant arrhythmias, and even sudden cardiac death

[56][52]. The AnkB-p.Glu1458Gly variant was linked to AnkB syndrome but was also identified in a family with AnkB syndrome found to have ARVC at autopsy

[27]. A larger screen that encompassed AnkB variants in ACM revealed a loss-of-function variant, AnkB-p.Met1988Thr, which segregated with ARVC-affected family members, where staining of the ventricle tissue showed reduced levels of NCX at the plasma membrane and abnormal Z-line targeting

[27]. In order to model the ACM phenotype seen in these patients with loss-of-function AnkB variants and ACM, a cardiomyocyte-specific AnkB knockout mouse was generated (as AnkB null mice die shortly after birth), which developed a phenotype similar to that of human ACM, including dramatic structural abnormalities, biventricular dilation, reduced ejection fraction, cardiac fibrosis, premature death, and exercise-induced death

[27]. Although the desmosome was preserved in these mice, β-catenin localization was altered, and β-catenin was demonstrated as a binding partner for the AnkB MBD. Interestingly, when these mice were treated with GSK-3β-inhibitor, a pharmacological activator of β-catenin, it prevented and partially reversed the ARVC phenotype found in these mice

[27], providing a hopeful outlook on developing new therapies for patients with AnkB variant-driven ARVC.