Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Masashi Kotobuki.

Ceramics and polymers are two main candidate materials for membranes, where the majority has been made of polymeric materials, due to the low cost, easy processing, and tunability in pore configurations. In contrast, ceramic membranes have much better performance, extra-long service life, mechanical robustness, and high thermal and chemical stabilities, and they have also been applied in gas, petrochemical, food-beverage, and pharmaceutical industries, where most of polymeric membranes cannot perform properly.

- composite membrane

- polymeric membrane

- ceramic membrane

- nanocomposite

1. Introduction

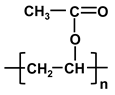

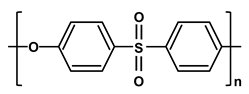

Ceramics and polymers are the two main materials for various membranes. In particular, ceramic membranes have gained more attention recently, due to their superior performance, hydrophilicity, mechanical robustness, and high thermal and chemical stabilities, which allow at least double lifespan compared with the polymer membranes [20,21][1][2]. The common ceramic materials used in membrane applications are Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2, SiO2 [19[3][4],22], and those containing a combination of them such as Al2O3-ZrO2 [23][5] and TiO2-SiO2 [24][6], and various metal nanoparticles embedded in ceramics such as Ag-TiO2 [25][7]. However, the relatively high production cost of the ceramic membranes is a restricting parameter in widening of their applications. Indeed, polymeric materials are still more widely used, although there is a steadily decrease in the overall market share. Polymer membranes have the merits of being low cost, tunable in porous structure, and ease in scale-up. Therefore, the polymer membranes have been dominantly employed for water, wastewater treatment, and desalination [1][8]. Among them, Poly-ethersulfone (PES) [26][9], Poly-sulfone (PSf) [27][10], poly-vinylidene fluoride (PVDF) [28[11][12],29], poly-vinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [30][13], poly-acrylonitrile (PAN) [31,32][14][15], poly-vinyl alcohol (PVA) [33[16][17],34], and poly-vinyl acetate (PVAc) [35][18] are widely used as the polymeric membranes (Table 1). In addition to the poor life span, most of these polymeric membranes are inherently hydrophobic to certain extent, leading to low water flux, high fouling tendency, which often causes even shorter lifetime and higher operating cost.

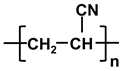

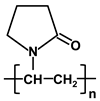

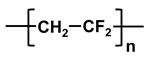

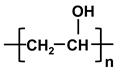

Table 1. Structures of common polymer membranes.

| Polymer | Abbreviation | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| poly-acrylonitrile | PAN |  |

| poly-vinylpyrrolidone | PVP |  |

| poly-vinylidene fluoride | PVDF |  |

| poly-vinyl alcohol | PVA |  |

| poly-vinyl acetate | PVAc |  |

| Poly-ethersulfone | PES |  |

| Poly-sulfone | PSf |

2. Ceramic-Polymer Composite Membrane

Ceramic-polymer composite membranes can be divided into three groups. Nanocomposite membranes are composed of a polymeric membrane in which inorganic NPs are dispersed. This type of membranes has been most widely researched. The preparation for the nanocomposite membrane is mostly-based those well developed for polymer membranes, such as the phase inversion or casting of a polymer solution containing ceramic NPs. Either flat sheet or hollow fiber configurations can be obtained. The nanocomposite membrane has been used for both MF and UF processes. In the TFN membranes, a thin nanocomposite membrane is supported on a polymeric support, where ceramic NPs are located on the surface of the membrane and provide minimal influence on the intrinsic properties of polymeric substrate such as the pore structure. The surface properties of the resultant membrane are basically governed by ceramic NPs. The ceramic-supported polymer membranes consist of a thin polymer layer on a porous ceramic support. In contrast to the other two types of membranes, relatively dense and bulk ceramics, not ceramic NPs, are used in this type of membranes. The high chemical and thermal stability of ceramic supports restrict swelling of the thin polymer layer and improve flux and provide long membrane life. Highly tunable pore distribution and pore size of the polymeric surface layer influence the rejection properties of composite membranes. Coating on a polymer solution or in situ polymerization on a ceramic support has been employed to prepare the ceramic-support membranes. In all three types of membranes, not only the intrinsic properties of ceramic and polymeric components but also the interface properties between them influence the membrane performance significantly.

2.1. Ceramics in Polymer (Nanocomposite) Membranes

This type of membranes is composed of polymeric membranes in which ceramic NPs are dispersed in. Incorporation of the ceramic NPs into polymers could influence not only the hydrophilicity, pore size and distribution, surface roughness, but also can add new properties such as photocatalytic properties, antibacterial properties, etc. [60][19]. The fabrication of these membranes is mainly performed by casting and phase inversion (PI) using a polymer solution containing ceramic NPs [61][20].

Metal oxides such as SiO2, Al2O3, TiO2, Fe3O4 have been exclusively used as ceramic fillers for the nanocomposite membranes, where TiO2 is one of the most widely used ceramics in this type of membranes. Additionally, natural minerals such as kaolin [62][21], cloisite [63][22] and montmorillonite [64][23] are studied to reduce material cost for inorganic components. The main advantages of TiO2 incorporation include the enhancement in hydrophilicity as well as antibacterial behavior by photocatalytic properties of TiO2 [65][24]. By the addition of TiO2, a decrease in contact angle and improvement of water flux have been reported by several groups. Additionally, UV-radiation enhances fouling resistance and antibacterial capability of TiO2-nanocomposite membranes due to the superhydrophilicity and photocatalysis of TiO2 under UV irradiation [66,67][25][26]. The UV irradiation also promote flux recovery of the TiO2-nanocomposite membrane [68][27].

The enhancement in hydrophilicity by the addition of ceramic NPs has also been observed in other transition metal oxides, such as SiO2 [81,82[28][29][30][31][32][33],83,84,85,86], Al2O3 [87[34][35][36][37],88,89,90], Fe3O4 [91[38][39][40][41][42],92,93,94,95], and ZrO2 [96][43]. The influence of these ceramic fillers on the properties of polymeric membranes is dependent on the type and amount of fillers being added. For example, the addition of mesoporous silica into PES UF membrane does not affect the pore size significantly, but increases the level of porosity, resulting in an improved water flux [85][32]. Contrarily, the addition of Fe3O4 into PES membrane largely influences both pore size and the level of porosity [94][41]. The level of porosity increased by the Fe3O4 addition, while the pore size drastically decreased.

2.2. Thin Film Nanocomposite (TFN) Membranes

This type of membranes is composed of a thin nanocomposite membrane supported on polymer substrates. The concept of TFN membrane was first suggested in the 1970s, and it has been widely studied for desalination of seawater/brackish water, removal of heavy metals, organic micropollutants and pharmaceutically active compounds [61][20]. PSf has widely been used as a supporting layer while PA (polyamide) has been widely employed in the thin top layer. As inorganic compounds, (a) metal oxide NPs, (b) metal NPs and (c) carbon materials such as CNT and GO have been studie.

As in the nanocomposite membranes, TiO2 nanoparticles are among the most used in the thin top layer, and the water flux and antifouling properties are improved [49,100,101,102][44][45][46][47]. An optimum TiO2 loading in this type of membrane is reported as 0.05~0.1 wt.%. This is much lower than that in TiO2-nanocomposite membranes, which is around 1 wt.%. In the TFN configuration, TiO2 content can be drastically reduced. Exposing TiO2 NPs on the surface significantly influences surface properties of membranes, resulting in reduction of TiO2 content. The TFN membrane could be fabricated at lower material cost compared to the nanocomposite membrane. In contrast, photocatalytic properties of TiO2 in the TFN membranes have not been widely reported. The optimum ceramic NP content is also in the same range (0.05–0.1 wt.%) in the case of SiO2 NPs [103][48].

2.3. Ceramic-Supported Polymer Membranes

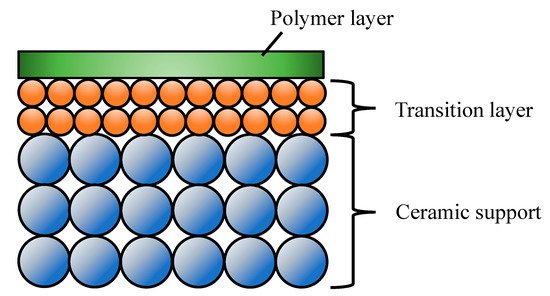

This type of membrane is composed of a thin polymeric film (selective layer, active layer) supported on a ceramic porous substrate (Figure 31, [140][49]). The ceramic substrates provide the superior chemical, mechanical and thermal stabilities as well as negligible transport resistance and defines the external shape of the membrane [44][50]. The ceramic-supported polymer composites have attracted much attention for their significant performance in UF [141][51], pervaporation [44[50][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][49][51][59][60][61][62][63][64],133,134,135,136,137,138,139,140,141,142,143,144,145,146,147], gas separation [148][65], etc. The thin polymeric layer, which can consist of one or more intermediate layers, is prepared by processes, such as interfacial polymerization, dip coating, etc. The level of air humidity during dip coating, drying process and polymer solution affected quality of top thin layer significantly [148,149][65][66].

Figure 31.

Structure of the ceramic-supported polymer composites.

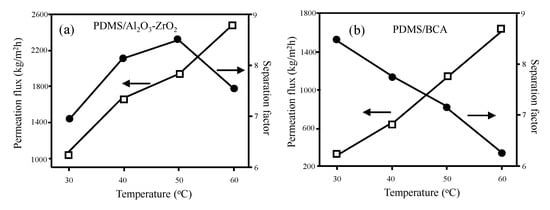

The benefits offered by the ceramic-supported polymer membranes are mainly in high flux and long-term stability. For example, PDMS/Al2O3-ZrO2 nanocomposite membrane shows about two times higher pervaporation flux of ethanol/water than that of the PDMS/Blend cellose acetate (BCA) membrane [163][67] (Figure 42). Additionally, the separation factor decreased with temperature monotonically in the PDMS/BCA membrane, while the peak of separation factor was shown at 50 °C in the PMDS/Al2O3.

Additionally, their superior long-term stability are reported by several research groups [148[65][68][69][67],150,159,163], where it is considered to be arising from the high structural, thermal, and chemical stabilities of ceramic supports in operating condition. In the polymer-supported membranes, swelling of the polymeric support in the operation could damage the thin top layer, resulting in poor stability of the polymer-supported membranes. The swelling tendency is more prominent at high temperatures. Therefore, most of the commercial PA membranes with polymer support cannot be used above 50 °C. Contrarily, PA supported on Al2O3 tubular membrane demonstrated stable rejection and permeation of MgCl2 at 70 °C, due to the high stability of Al2O3 support which could stabilize the PA top layer [152][70].

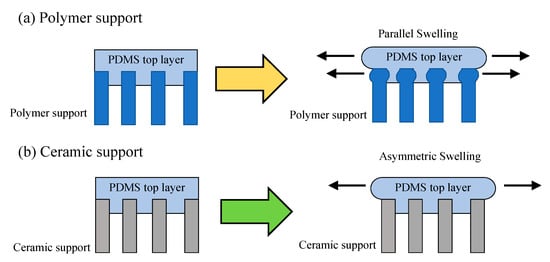

It must be noted that the swelling process is different between the polymer-supported and ceramic-supported polymer membranes (Figure 53) [163][67]. In the polymer support, top and support layers are swollen in a parallel direction together (Figure 53a). The swelling influences pore structure and membrane performance. On the contrary, only the top layer can be swollen in the ceramic-support membranes (Figure 53b). The ceramic support maintains its pore structure and can suppress the swelling of top polymeric layer. Therefore, influence of the swelling is reduced in the polymer-supported membranes. This would be one of the reasons behind the superior performance of the ceramic-supported composite polymer membranes.

Ceramic-supported polymer composite membranes can recover their performance completely by back washing after fouling [158][71]. For example, PDMS/β-Sialon membrane is fouled by the crystallization of NaCl. After the membrane is scoured and dried to remove the crystallized NaCl on the surface, the flux could be completely recovered. Interestingly, for example, Menne et al. reported a reusable Al2O3 monolith support for PDADMAC/PSS (poly(sodium 4-styrene sulfonate)) film [157][72]. After fouling, the top PDADMAC/PSS layer is removed by sodium hypochlorite (NaOCl) treatment. Then, a new top layer is built by the coating on the same Al2O3 monolith. Pure water permeability does not change by the removal and rebuilding of the top layer. This reusable ceramic support is expected to reduce material and production costs drastically.

By properly matching the properties between the ceramic support and a polymeric top layer, the ceramic-supported polymer composite membranes can feature high permeability. Additionally, the confinement in swelling of the polymeric top layer by a stable ceramic support provides long-term stability and allows high temperature operation. However, further research would be required to optimize the polymer-ceramic interface, in order to tailor the high performance of the ceramic-supported polymer composite membranes.

References

- Ng, L.Y.; Mohammad, A.W.; Leo, C.P.; Hilal, N. Polymeric membranes incorporated with metal/metal oxide nanoparticles: A comprehensive review. Desalination 2013, 308, 15–33.

- Gitis, V.; Rothenberg, G. Ceramic Membranes: New Opportunities and Practical Applications; Willey-VCH Verlag GmbH&Co.: Weinheim, Germany, 2016.

- He, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Ceramic-based membranes for water and wastewater treatment. Colloids Surf. A 2019, 578, 123513.

- DeFriend, K.A.; Wiesner, M.R.; Barron, A.R. Alumina and aluminate ultrafiltration membranes derived from alumina nanoparticles. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 224, 11–28.

- Li, F.B.; Yang, Y.; Fan, Y.Q.; Xing, W.H.; Wang, Y. Modification of ceramic membranes for pore structure tailoring: The atomic layer deposition route. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 397, 17–23.

- Wen, Q.; Di, J.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Yu, J. Flexible inorganic nanofibrous membranes with hierarchiral porosity for efficient water purification. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 4378–4382.

- Liu, L.; Liu, Z.Y.; Bai, H.W.; Sun, D.D. Concurrent filtration and solar photocatalytic disinfection/degradation using high performance Ag/TiO2 nanofiber membrane. Water Res. 2012, 46, 1101–1112.

- Yang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, Z.; Rui, X.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Z. A review on reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes for water purification. Polymers 2019, 11, 1252.

- Ahmad, A.L.; Abdulkarim, A.A.; Ooi, B.S.; Ismail, S. Recent development in additives modifications of polyethersulfone membrane for flux enhancement. Chem. Eng. J. 2013, 223, 246–267.

- Saljoughi, E.; Mousavi, S.M. Preparation and characterization of novel polysulfone nanofiltration membranes for removal of cadmium from contaminated water. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2012, 90, 22–30.

- Yuliwati, E.; Ismail, A.F. Effect of additives concentration on the surface properties and performance of PVDF ultrafiltration membranes for refinery produced wastewater treatment. Desalination 2011, 273, 226–234.

- Liu, F.; Hashim, N.A.; Liu, Y.; Abed, M.R.M.; Li, K. Progress in the production and modification of PVDF membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 375, 1–27.

- Yu, S.; Zhang, X.; Li, F.; Zhao, X. Poly(vinyl pyrrolidone) modified poly(vinylidene fluoride) ultrafiltration membrane via a two-step surface grafting for radioactive wastewater treatment. Sep. Purif. Techol. 2018, 194, 404–409.

- Lohokare, H.R.; Muthu, M.R.; Agarwal, G.P.; Kharul, U.K. Effective arsenic removal using polyacrylonitrile-based ultrafiltration (UF) membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 320, 159–166.

- Kim, I.C.; Yun, H.G.; Lee, K.H. Preparation of asymmetric polyacrylonitrile membrane with small pore size by phase inversion and post-treatment process. J. Membr. Sci. 2002, 199, 75–84.

- Unlu, D. Recovery of cutting oil from wastewater by pervaporation process using natural clay modified PVA membrane. Water Sci. Tech. 2019, 80, 2404–2411.

- Moradi, E.; Ebahimzdeh, H.; Mehrani, Z.; Asgharinezhad, A.A. The efficient removal of methylene blue from water samples using three-dimensional poly(vinyl alcohol)/starch nanofiber membrane as a green nanosorbent. Environ. Sci. Poll. Res. 2019, 26, 35071–35081.

- Esmaeili, N.; Boyd, S.E.; Brown, C.L.; Gray, E.M.A.; Webb, C.J. Improving the gas-separation properties of PVAc-Zeolite 4A mixed-matrix membranes through nano-sizing silanation of the Zeolite. Chem. Phys. Chem. 2019, 20, 1590–1606.

- Kim, H.J.; Pant, H.R.; Kin, J.H.; Choi, N.J.; Kim, C.S. Fabrication of multifunctional TiO2-fly ash/polyurethane nanocomposite membrane via electrospinning. Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 3023–3029.

- Yin, J.; Deng, B. Polymer-matrix nanocomposite membranes for water treatment. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 479, 256–275.

- Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, N. Polyvinylamine/amorphous metakaolin mixed-matrix composite membranes with facilitated transport carriers for highly efficient CO2/N2 separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 599, 117828.

- Daraei, P.; Ghaemi, N. Synergistic effect of Cloisite 15A and 30B nanofillers on the characteristics of nanocomposite polyethersulfone membrane. Appl. Clay Sci. 2019, 172, 96–105.

- Shokri, E.; Shahed, E.; Hermani, M.; Etemadi, H. Towards enhanced fouling resistance of PVC ultrafiltration membrane using modified montmorillonite with folic acid. Appl. Clay Sci. 2021, 200, 105906.

- Paz, Y. Application of TiO2 photocatalysis for air treatment: Patents’ overview. Appl. Catal. B 2010, 99, 448–460.

- Rahimpour, A.; Madaeni, S.S.; Taheri, A.H.; Mansourpanah, Y. Coupling TiO2 nanoparticles with UV irradiation for modification of polyethersulfone ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 313, 158–169.

- Damodar, R.A.; You, S.-J.; Chou, H.-H. Study the self cleaning, antibacterial and photocatalytic properties of TiO2 entrapped PVDF membranes. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 172, 1321–1328.

- Yu, L.-Y.; Shen, H.-M.; Xu, Z.-L. PVDF-TiO2 composite hollow fiber ultrafiltration membranes prepared by TiO2 sol-gel method and blending method. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2009, 113, 1763–1772.

- Sun, M.; Su, Y.; Mu, C.; Jiang, Z. Improved antifouling property of PES ultrafiltration membranes using additive of silica-PVP nanocomposite. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2010, 49, 790–796.

- Jomekian, A.; Mansoori, S.A.A.; Monirimanesh, N. Synthesis and characterization of novel PEO-MCM-41/PVDC nanocomposite membrane. Desalination 2011, 276, 239–245.

- Shen, J.N.; Ruan, H.M.; Wu, L.G.; Gao, C.J. Preparation and characterization of PES-SiO2 organic-inorganic composite ultrafiltration membrane for raw water pretreatment. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 168, 1272–1278.

- Muriithi, B.; Loy, D.A. Processing, morphology, and water uptake of nafion/Ex-situ stöber silica nanocomposite membranes as a function of particle size. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 4, 6766–6773.

- Huang, J.; Zhang, K.; Wang, K.; Xie, Z.; Ladewig, B.; Wang, H. Fabrication of polyethersulfone-mesoporous silica nanocomposite ultrafiltration membranes with antifouling properties. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 423–424, 362–370.

- Wu, H.; Tang, B.; Wu, P. Development of novel SiO2-GO nanohybrid/poly-sulfone membrane with enhanced performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2014, 451, 94–102.

- Yan, L.; Hong, S.; Li, M.L.; Li, Y.S. Application of the Al2O3-PVDF nanocomposite tubular ultrafiltration (UF) membrane for oily wastewater treatment and its antifouling research. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2009, 66, 347–352.

- Maximous, N.; Nakhla, G.; Wan, W.; Wong, K. Preparation, characterization and performance of Al2O3/PES membrane for wastewater filtration. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 341, 67–75.

- Maximous, N.; Nakhla, G.; Wong, K.; Wan, W. Optimization of Al2O3/PES membranes for wastewater filtration. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2010, 73, 294–301.

- Maximous, N.; Nakhla, G.; Wan, W.; Wong, K. Effect of the metal oxide particle distributions on modified PES membranes characteristics and performance. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 361, 213–222.

- Csetneki, I.; Filipcsei, G.; Zrínyi, M. Smart nanocomposite polymermembranes with on/off switching control. Macromolecules 2006, 39, 1939–1942.

- Daraei, P.; Madaeni, S.S.; Ghaemi, N.; Salehi, E.; Khadivi, M.A.; Moradian, R.; Astinchap, B. Novel polyethersulfone nanocomposite membrane prepared by PANI/Fe3O4 nanoparticles with enhanced performance for Cu(II) removal from water. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 415–416, 250–259.

- Gholami, A.; Moghadassi, A.R.; Hosseini, S.M.; Shabani, S.; Gholami, F. Preparation and characterization of polyvinylchloride based nanocomposite nanofiltration-membrane modified by iron oxide nanoparticles for lead removal from water. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2014, 20, 1517–1522.

- Alam, J.; Dass, L.A.; Ghasemi, M.; Alhoshan, M. Synthesis and optimization of PES-Fe3O4 mixed matrix nanocomposite membrane: Application studies in water purification. Polym. Compos. 2013, 34, 1870–1877.

- Daraei, P.; Madaeni, S.S.; Ghaemi, N.; Khadivi, M.A.; Astinchap, B.; Moradian, R. Fouling resistant mixed matrix polyethersulfone membranes blended with magnetic nanoparticles: Study of magnetic field induced casting. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2013, 109, 111–121.

- María Arsuaga, J.; Sotto, A.; del Rosario, G.; Martínez, A.; Molina, S.; Teli, S.B.; de Abajo, J. Influence of the type, size, and distribution of metal oxide particles on the properties of nanocomposite ultrafiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 428, 131–141.

- Ghanbari, M.; Emadzadeh, D.; Lau, W.J.; Matsuura, T.; Davoody, M.; Ismail, A.F. Super hydrophilic TiO2/HNT nanocomposites as a new approach for fabrication of high performance thin film nanocomposite membranes for FO application. Desalination 2015, 371, 104–114.

- Rajaeian, B.; Rahimpour, A.; Tade, M.O.; Liu, S. Fabrication and characterization of polyamide thin film nanocomposite (TFN) nanofiltration membrane impregnated with TiO2 nanoparticles. Desalination 2013, 313, 176–188.

- Ghanbari, M.; Emadzadeh, D.; Lau, W.J.; Lai, S.O.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F. Synthesis and characterization of novel thin film nanocomposite TFN) membranes embedded with halloysite nanotubes (HNTs) for water deslination. Desalination 2015, 358, 33–41.

- Emadzadeh, D.; Ghanbari, M.; Lau, W.J.; Rahbari-Sisakht, M.; Matsuura, T.; Ismail, A.F.; Kruczek, B. Solvothermal synthesis of nanoporous TiO2: The impact on thin-film composite membranes for engineered osmosis application. Nanotechnology 2016, 27, 345702.

- Niksefat, N.; Jahanshahi, M.; Rahimpour, A. The effect of SiO2 nanoparticles on morphology and performance of thin film composite membranes for forward osmosis application. Desalination 2014, 343, 140–146.

- Perreault, F.; Jaramillo, H.; Xie, M.; Ude, M.; Nghiem, L.D.; Elimelech, M. Biofouling mitigation in forward osmosis using graphene oxide functionalized thin-film composite membranes. Environ. Sci. Tech. 2016, 50, 5840–5848.

- Liu, G.; Wei, W.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. Polymer/ceramic composite membranes and their application in pervaporation process. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2012, 20, 62–70.

- Marchetti, P.; Solomon, M.F.J.; Szekely, G.; Livingston, A.G. Molecular separation with organic solvent nanofiltration: A critical review. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10735–10806.

- Chen, C.; Yang, Q.-H.; Yang, Y.; Lv, W.; Wen, Y.; Hou, P.-X.; Wang, M.; Cheng, H.-M. Self-assembled free-standing graphite oxide membrane. Adv. Mater. 2009, 21, 3007–3011.

- Backes, C.; Hauke, F.; Hirsch, A. The potential of perylene bisimide derivatives for the solubilization of carbon nanotubes and graphene. Adv. Mater. 2011, 23, 2588–2601.

- Li, F.; Bao, Y.; Chai, J.; Zhang, Q.; Han, D.; Niu, L. Synthesis and application of widely soluble graphene sheets. Langmuir 2010, 26, 12314–12320.

- Hung, W.-S.; An, Q.-F.; De Guzman, M.; Lin, H.-Y.; Huang, S.-H.; Liu, W.-R.; Hu, C.-C.; Lee, K.-R.; Lai, J.-Y. Pressure-assisted self-assembly technique for fabricating composite membranes consisting of highly ordered selective laminate layers of amphiphilic graphene oxide. Carbon 2014, 68, 670–677.

- Hegab, H.M.; Zou, L. Graphene oxide-assisted membranes: Fabrication and potential applications in desalination and water purification. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 484, 95–106.

- Faria, A.F.; Liu, C.; Xie, M.; Perreault, F.; Nghiem, L.D.; Ma, J.; Elimelech, M. Thin-film composite forward osmosis membranes functionalized with graphene oxide-silver nanocomposites for biofouling control. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 525, 146–156.

- Inurria, A.; Cay-Durgun, P.; Rice, D.; Zhang, H.; Seo, D.-K.; Ling, M.L.; Perreault, F. Polyimide thin-film nanocomposite membrane with graphene oxide nanosheets: Balancing membrane performance and fouling propensity. Desalination 2018, 451, 139–147.

- Matsumoto, Y.; Sudoh, M.; Suzuki, Y. Preparation of composite UF membranes of sulfonated polysulfone coated on ceramics. J. Membr. Sci. 1999, 158, 55–62.

- Peters, T.A.; Poeth, C.H.S.; Benes, N.E.; Bujis, H.C.W.M.; Vercauteren, F.F.; Keurentjes, J.T.F. Ceramic-supported thin PVA pervaporation membranes combining high flux and high selectivity; contradicting the flux-selectivity paradigm. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 276, 42–50.

- Yoshida, W.; Cohen, Y. Removal of methyl tert-butyl ether from water by pervaporation using ceramic-supported polymer membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2004, 229, 27–32.

- Xiangli, F.; Chen, Y.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS)/ceramic composite membrane with high flux for pervaporation of ethanol-water mixtures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 2224–2230.

- Zhu, Y.; Xia, S.; Liu, G.; Jin, W. Preparation of ceramic-supported poly(vinyl alcohol)-chitosan composite membranes and their applications in pervaporation dehydration of organic/water mixtures. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 349, 341–348.

- Chen, Y.; Xiangli, F.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. Organic-inorganic composite pervaporation membranes prepared by self-assembly of polyelectrolyte multilayers on microporous ceramic supports. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 302, 78–86.

- Randon, J.; Paterson, R. Preliminary studies on the potential for gas separation by mesoporous ceramic oxide membranes surface modified by alkyl phosphonic acids. J. Membr. Sci. 1997, 134, 219–223.

- Lu, M.; Hu, M.Z. Novel porous ceramic tube-supported polymer layer membranes for acetic acid/water separation by pervaporation dewatering. Sep. Purif. Tech. 2020, 236, 116312.

- Wei, W.; Xia, S.; Liu, G.; Dong, X.; Jin, W.; Xu, N. Effects of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) molecular weight on performance of PDMS/ceramic composite membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 375, 334–344.

- Chen, G.; Zhu, H.; Hang, Y.; Liu, Q.; Liu, G.; Jin, W. Simultaneously enhancing interfacial adhesion and pervaporation separation performance of PDMS/ceramic composite membrane via a facile substrate surface grafting approach. AIChE J. 2019, 65, 16773.

- Liu, G.; Wei, W.; Wu, H.; Dong, X.; Jiang, M.; Jin, W. Pervaporation performance of PDMS/ceramic composite membrane in acetone butanol ethanol (ABE) fermentation-PV coupled process. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 373, 121–129.

- Chong, J.Y.; Wang, R. From micro to nano: Polyamide thin film on microfiltration ceramic tubular membranes for nanofiltration. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 587, 117161.

- Wang, J.-W.; Li, X.-Z.; Fan, M.; Gu, J.-Q.; Hao, L.-Y.; Xu, X.; Chen, C.-S.; Wang, C.-M.; Hao, Y.-Z.; Agathopoulos, S. Porous β-sialon planar membrane with a robust polymer-derived hydrophobic ceramic surface. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 535, 63–69.

- Amirilargani, M.; Merlet, R.B.; Nijmeijer, A.; Winnubst, L.; de Smet, L.C.P.M.; Sudholter, E.J.R. Poly (maleic anhydride-alt-1-alkenes) directly grafted to γ-alumina for high-performance organic solvent nanofiltration membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 564, 259–266.

More