SF1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus are a specific lead in the brain’s ability to sense glucose levels and conduct insulin and leptin signaling in energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis. This neuronal population is therefore playing a critical role in hypothalamic regulation of diabetes and obesity.

- SF1 neurons

- ventromedial hypothalamus nucleus

- obesity

- diabetes

- energy homeostasis

- glucose homeostasis

1. Introduction

Obesity is a multifactorial chronic disease associated with a higher risk of developing cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer, and, more recently, COVID-19 infection. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2016, worldwide obesity had nearly tripled since 1975, with 39% of adults and 18% of children and adolescents overweight or obese [1]. The main metabolic comorbidity of obesity is type-2 diabetes that occurs when body tissues become resistant to insulin and is estimated to be the seventh leading cause of death [2]. Therefore, understanding the molecular and physiological mechanisms underlying the control of feeding behavior, energy balance and glucose homeostasis is crucial for the prevention and treatment of obesity and diabetes.

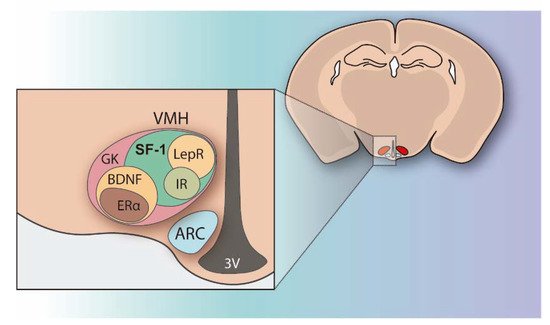

The regulation of peripheral metabolism and glucose homeostasis not only resides in the tissue The hypothalamus integrates multiple metabolic inputs from peripheral organs with afferent stimuli coming from other brain regions and coordinates a diversity of efferent responses to control food intake, fat metabolism, hormone secretion, body temperature, locomotion, and behavior in order to maintain energy balance and blood glucose levels. Within the hypothalamus, the ventromedial nucleus (VMH) located above the arcuate nucleus (ARC) and the median eminence, was identified in the mid-1900s as the satiety center because its injury produced hyperphagia, insulin resistance, and body weight gain [3][4][3,4]. At that point, VMH was demonstrated to play a key role in the control of energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis [3][5][3,5]. Since then, intensive research has been done on VMH and it is currently known that this hypothalamic area encompasses a heterogeneous set of neurons, which are differentiated by the genes they are expressing (Figure 1). Many of the genes highly expressed in the VMH have been identified and their functions have been explored (Figure 1) [6][7][8][6,7,8].

Interestingly, SF1 can suffer different post-translational modifications, which regulate its stability and transcriptional activity [9][14], but also control the expression of numerous downstream target genes, including CB1, BDNF, and Crhr2 [10][13]. Considering this, in order to explore the importance of SF1 neurons, transgenic mice lacking this nuclear receptor were studied by different researchers. However, when rescued from lethality by adrenal transplantation from WT littermates and corticosteroid injections, mutant mice displayed robust weight gain resulting from both hyperphagia and reduced energy expenditure [11][16]. These postnatal VMH-specific SF1 KO mice showed increased weight gain and impaired thermogenesis in response to a high-fat diet (HFD), being the first demonstration that the transcription factor SF1 is postnatally required in the VMH for normal energy homeostasis, especially under the HFD condition.

In an attempt to clarify the contribution of this specific population of neurons to hypothalamic regulation of obesity and diabetes, in the last 15 years, several transgenic models have been developed by deleting specific targets in SF1 neurons related to energy balance and glucose homeostasis. In 2013, a profound review article was published by Choi and colleagues [8] summarizing the last updates of SF1 neurons in energy homeostasis. Since then, new neuronal-based approaches (i.e., optogenetic and chemogenetic technology) and the generation of new transgenic mice in key target proteins have provided exciting insight into the implication of SF1 neurons on whole-body energy balance, particularly thermogenesis and glucose homeostasis, that are compiled in the present review.

2. Unraveling the Functions of SF1 Neurons in Energy Balance by Optogenetic and Chemogenetic Approaches

In order to selectively manipulate the SF1 neuronal activity in a physiological context, optogenetic and chemogenetic approaches have emerged [12][13][21,22]. These tools use channels that are activated by light and engineered G-protein coupled receptors controlled by exogenous molecules, respectively [12][13][21,22]. The incorporation of these approaches into animal models has greatly advanced our understanding of the SF1 role and neuronal circuits.

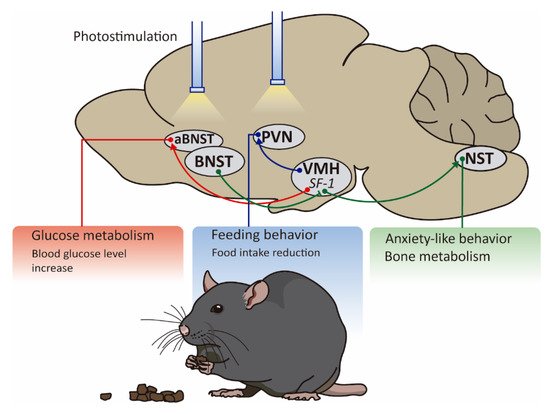

Mice engineered to activate SF1 neurons by optogenetics were designed through the injection of adeno-associated virus (AAV) particles expressing a Cre-dependent channelrhodopsin (ChRs) into the VMH of SF1-Cre mice to produce SF1-ChRs animals [14][15][23,24]. The advantage of this technology is the light-controllable activation of SF1 neurons in a spatiotemporal manner.

David J. Anderson and colleagues in 2015, demonstrated that the optogenetic stimulation of SF1 neurons applying a frequency of 20 Hz induced freezing or activity burst, while no response on feeding behavior or energy balance was reported [16][25]. Considering this information, two years later, other researchers showed that SF1 neurons exert a differential effect depending on the frequency of activation. They confirmed that high-frequency activation (>20 Hz) evokes a profound defensive response which includes freezing and escape attempts, but low-frequency activation (2 Hz) suppresses feeding after fasting and reduces the time that mice spend near to the food [15][24]. These novel results suggest that SF1 neurons dynamically modulate feeding and anxiety-related behaviors by changing the firing pattern and also indicate that this subset of hypothalamic neurons is involved in the fight or flight response.

These changes in fat mass could be explained by the SF1 modulation of fat oxidation. Very recently, it was established that SF1-hM3Dq mice increased energy expenditure and fat oxidation independent of the locomotion activity within 2-h post-activation [14][23]. Although this study did not evaluate the energy expenditure profile in SF1-hM4Di mice, it was expected that the inactivation of SF1 neurons reduced energy expenditure. Since TT prevents neurotransmitter release, SFTTmice displayed reduced energy expenditure and increased body weight [17][29].

Besides their implication in energy balance, the use of optogenetics has highlighted the role of SF1 neurons in the hypothalamic control of systemic glucose levels. For a long time, it was known that VMH triggered the counterregulatory response (CRR) induced by hypoglycemia [18][19][30,31] but it was not clear the contribution of SF1 neurons to this feedback response. In order to elucidate whether SF1 neurons are linked to this effect, an elegant experiment using optogenetic and chemogenetic tools was done by Gregory J Morton and colleagues, showing that selective inhibition of SF1 neurons blocked recovery from insulin-induced hypoglycemia. This evidence is concordant with those obtained from transgenic models such as mice lacking vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (VGLUT2) specifically in SF1 neurons since this genetic disruption attenuated recovery from insulin-induced hypoglycemia [20][33].

Taken all together, these genetic approaches have revealed the specific involvement of SF1 neurons in many aspects of metabolic regulation due to their direct or indirect role in the maintenance of the energy balance and glucose levels, confirming the classification of VMH as a primary satiety center [21][22][34,35].

3. Manipulation of Key Targets in SF1 Neurons: Lessons from Transgenic Mice

A particularly powerful strategy developed for the exploration of SF1 neurons in obesity and diabetes has been the design of the SF1 Cre mice. Several groups have generated different SF1 Cre transgenic lines in which the expression of Cre recombinase is derived bySf1regulatory elements [23][24][20,36]. These lines allow for ablating general factors or targets known to be associated with energy homeostasis by crossing them withfloxedstrains. In the following sub-sections, we discuss different studies of SF1-CRE transgenic mice organized by the type of molecular target under investigation (Table 1) as well as the sex-specific effect of SF1 neurons in energy balance.

| ] | ||||||||||||||

| [ | ||||||||||||||

| 60 | ||||||||||||||

| ] | ||||||||||||||

| M | ||||||||||||||

| HFD | ||||||||||||||

| ↑ | ||||||||||||||

| ↑ | ||||||||||||||

| n.s. | ||||||||||||||

| ↑ | ||||||||||||||

| - | ||||||||||||||

| ↓ | ||||||||||||||

| n.s. | ||||||||||||||

| ↓ | ||||||||||||||

| ↓ | ||||||||||||||

| Modulators of autophagy, mitochondrial and primary cilia function | ||||||||||||||

| Atfg7 | ||||||||||||||

| Sf1-Cre; | ||||||||||||||

| Atg7 | ||||||||||||||

| loxP/loxP | ||||||||||||||

| M | Fasting | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ | - | [ | 39 | ] | [61] |

| UCP2 | Ucp2KOKISf1 | M | Chow diet | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | [40][62] | |

| IFT88 | IFT88-KOSF−1 | M/F | Chow diet | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | [41][63] | |

| M/F | HFD | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | - |

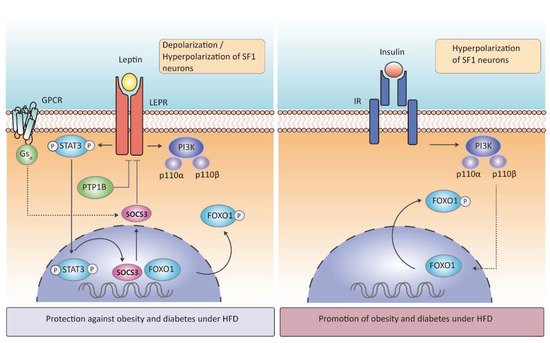

Due to the importance of the anorectic hormone leptin in the central control of energy homeostasis, the physiological effects after deletion of leptin receptor (LEPR) in SF1 neurons have been thoroughly investigated. The first and most representative study was performed by Bradford Lowell and colleagues, in which genetic deletion of LEPR selectively from hypothalamic SF1 neurons triggered an increase in body weight gain without changes in food intake, leaving these mice unable to adapt to HFD or to activate energy expenditure [23][20]. Conversely to the deletion of LEPR, mice lackingSocs3showed improved weight-reducing effects of leptin, with a decrease in food intake and an enhanced energy expenditure under chow diet or HFD condition [25][37]. The importance of leptin signaling in energy balance through SF1 neurons was also reinforced by the specific deletion of the G protein α-subunit

The protein-tyrosine phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) is another negative regulator of leptin signaling in SF1 neurons (Figure 2). In vivo studies have demonstrated that whole-brain deletion of PTP1B resulted in leanness, hypersensitivity to leptin, and resistance to HFD-induced obesity, a phenotype partly associated with increased hypothalamic activation of STAT3 Surprisingly, its specific deletion in SF1 neurons resulted in increased adiposity in female mice exposed to HFD due to low energy expenditure, whereas leptin sensitivity was enhanced, and food intake was attenuated, findings that were likely explained by increased STAT3 activation [42][40]. Mice lacking PTP1B in SF1 neurons also had improved leptin and insulin signaling in VMH, suggesting that increased insulin responsiveness in SF1 neurons could overcome leptin hypersensitivity and promote adiposity [27][42][39,40].

A more recent study tried to rescue native LEPR in SF1 neurons inLepR-deficient mice. They concluded that LEPR signaling in the VMH is not sufficient to protect against obesity in this null mouse [43][41]. This finding could explain that this neuronal population expressing LEPR works in conjunction with other types of neurons expressing the same receptor, and SF1 neurons by themselves cannot compensate for all receptor deficiency. Summing up, leptin signaling in SF1 neurons plays a key role in energy homeostasis regulation and mediates the proper physiological adaptation to HFD to avoid or delay the onset of obesity.

According to glucose metabolism, leptin has been long related to glucose homeostasis improving insulin sensitivity, since intra-VMH injection of leptin increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues [44][42] and normalizes hyperglycemia [45][43]. The essential action of leptin in SF1 to correct diabetic hyperglycemia was clarified by further investigations. Particularly, in the specific knock—out ofSocs3in SF1 neurons, where leptin signaling is over-activated, Ren Zhang and colleagues observed improved glucose homeostasis, showing protection against hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia caused by HFD feeding [25][37]. Optogenetic activation of SF1 neurons has the same output as leptin increasing glucose uptake

It is known that insulin acutely suppresses food intake and decreases fat mass in both rodents and humans [46][47][45,46] Mice lacking insulin receptors (IR) in SF1 neurons did not show any differences in body weight when fed a chow diet but under HFD conditions, mutant mice were protected against obesity and showed an enhanced leptin sensitivity and glucose homeostasis [28][26]. Interestingly, exposure to HFD led to the overactivation of insulin in the VMH, leading to a reduction in SF1 neurons firing frequency, in comparison to the insulin resistance induced in ARC neurons. However, the specific contribution of insulin signaling in SF1 neurons and its relationship to peripheral insulin resistance and glucose levels needs further investigation.

Mice lacking p110α in SF1 neurons had reduced energy expenditure in response to hypercaloric feeding and, therefore, displayed an obesogenic phenotype. Mice lacking p110β in the same neuronal population had also decreased energy expenditure (reduced thermogenesis) leading to increased susceptibility to obesity, whereas, in contrast to the p110α subunit, p110β involved changes in peripheral insulin sensitivity [30][50]. In line with this evidence, deletion of FOXO1, a downstream transcription factor of insulin-PI3K (Figure 2), in SF1 neurons resulted in a lean phenotype with high energy expenditure, even in fasting, and these null mice presented an enhanced insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance, in concordance with genetic deletion of IR in SF1neurons [31][51]. Although leptin and insulin can inhibit SF1 neurons using the same molecular cascade, they are anatomically segregated within the VMH (neurons expressing LEPR receptor are located in the VMHdm when depolarizing and scattered throughout the nucleus when hyperpolarizing, whereas those expressing IR are in the VMHc close to the ventricle)

Other hormones studied in SF1 neurons are estrogens. Female mice lacking the estrogenic receptor α (ERα) in SF1 neurons were obese due to a reduced energy expenditure [32][52]. Ablation of the ERα led to abdominal obesity with adipocyte hypertrophy in females, but not in male mice [48][53]. Despite the fact that most of the studies on SF1 neurons until now were performed only in male mice, these last results described, and others discussed later [42][35][40,54], reinforce the notion that SF1 neurons may have a sex-specific effect on energy balance and glucose metabolism.

Growth hormone (GH) also plays a role in glucose metabolism via SF1 neurons. GH is secreted in a metabolic stress situation such as hypoglycemia. Deletion of its receptor in SF1 neurons resulted in an impaired capacity for recovery from hypoglycemia [49][55]. This result supports the importance of SF1 neurons in the proper functionality of glucose homeostasis.

Altogether, these findings identify SF1 neurons (the predominant VMH population) as a key player in the regulation of energy expenditure and glucose homeostasis, being particularly important in the adaptive response to HFD feeding. Most of the mutant mice with deletion of several hormone receptors and associated proteins in SF1 neurons have no changes or mild metabolic alterations under chow diet, but they show substantial metabolic variations under HFD exposure. The action of hormones and related proteins in SF1 neurons is also involved in the CRR to hypoglycemia to maintain glucose balance between the brain and the periphery. Future studies are needed to describe the specific molecular mechanisms and subsets of SF1 neurons underlying the effects of hormones in glucose homeostasis and energy expenditure.

4. The Sex-Specific Effect of SF1 Neurons on Energy Balance

5. Exploring the Neurocircuitry That Links SF1 Neurons to Other Brain Areas in Energy Balance

6. Concluding Remarks and Future Perspectives

References

- World Health Organization. Obesity and Overweight. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- World Health Organization. Diabetes. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Hetherington, A.W.; Ranson, S.W. The relation of various hypothalamic lesions to adiposity in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1942, 76, 475–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington, A.W.; Ranson, S.W. Hypothalamic lesions and adiposity in the rat. Anat. Rec. 1940, 78, 149–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, W.P.; During, M.J.; Sherwin, R.S.; Borg, M.A.; Brines, M.L.; Shulman, G.I. Ventromedial hypothalamic lesions in rats suppress counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. J. Clin. Investig. 1994, 93, 1677–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, C.X.; Scherer, T.; Tschöp, M.H. Cajal revisited: Does the VMH make us fat? Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 806–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClellan, K.M.; Parker, K.L.; Tobet, S. Development of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2006, 27, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.-H.; Fujikawa, T.; Lee, J.; Reuter, A.; Kim, K.W. Revisiting the Ventral Medial Nucleus of the Hypothalamus: The Roles of SF-1 Neurons in Energy Homeostasis. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.C.; Kurrasch, D.M.; Liang, J.K.; Ingraham, H.A. Genetic labeling of steroidogenic factor-1 (SF-1) neurons in mice reveals ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH) circuitry beginning at neurogenesis and development of a separate non-SF-1 neuronal cluster in the ventrolateral VMH. J. Comp. Neurol. 2013, 521, 1268–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Ki, W.K.; Ikeda, Y.; Anderson, K.K.; Beck, L.; Chase, S.; Tobet, S.A.; Parker, K.L. Central nervous system-specific knockout of steroidogenic factor 1 results in increased anxiety-like behavior. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 1403–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, Y.; Luo, X.; Abbud, R.; Nilson, J.H.; Parker, K.L. The nuclear receptor steroidogenic factor 1 is essential for the formation of the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Mol. Endocrinol. 1995, 9, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parker, K.L.; Rice, D.A.; Lala, D.S.; Ikeda, Y.; Luo, X.; Wong, M.; Bakke, M.; Zhao, L.; Frigeri, C.; Hanley, N.A.; et al. Steroidogenic factor 1: An essential mediator of endocrine development. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 2002, 57, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoivik, E.A.; Lewis, A.E.; Aumo, L.; Bakke, M. Molecular aspects of steroidogenic factor 1 (SF-1). Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2010, 315, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Yang, D.J.; Lee, S.; Hammer, G.D.; Kim, K.W.; Elmquist, J.K. Nutritional conditions regulate transcriptional activity of SF-1 by controlling sumoylation and ubiquitination. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadovsky, Y.; Crawford, P.A.; Woodson, K.G.; Polish, J.A.; Clements, M.A.; Tourtellotte, L.M.; Simburger, K.; Milbrandt, J. Mice deficient in the orphan receptor steroidogenic factor 1 lack adrenal glands and gonads but express P450 side-chain-cleavage enzyme in the placenta and have normal embryonic serum levels of corticosteroids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 10939–10943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majdic, G.; Young, M.; Gomez-Sanchez, E.; Anderson, P.; Szczepaniak, L.S.; Dobbins, R.L.; McGarry, J.D.; Parker, K.L. Knockout Mice Lacking Steroidogenic Factor 1 Are a Novel Genetic Model of Hypothalamic Obesity. Endocrinology 2002, 143, 607–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achermann, J.C.; Ito, M.; Ito, M.; Hindmarsh, P.C.; Jameson, J.L. A mutation in the gene encoding steroidogenic factor-1 causes XY sex reversal and adrenal failure in humans [1]. Nat. Genet. 1999, 22, 125–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Fan, W.Q.; Nawata, H.; Yanase, T. The Gly146Ala variation in human SF-1 gene: Its association with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes in Chinese. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2006, 73, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.W.; Zhao, L.; Donato, J.; Kohno, D.; Xu, Y.; Elias, C.F.; Lee, C.; Parker, K.L.; Elmquist, J.K. Steroidogenic factor 1 directs programs regulating diet-induced thermogenesis and leptin action in the ventral medial hypothalamic nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 10673–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhillon, H.; Zigman, J.M.; Ye, C.; Lee, C.E.; McGovern, R.A.; Tang, V.; Kenny, C.D.; Christiansen, L.M.; White, R.D.; Edelstein, E.A.; et al. Leptin directly activates SF1 neurons in the VMH, and this action by leptin is required for normal body-weight homeostasis. Neuron 2006, 49, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berglund, K.; Tung, J.K.; Higashikubo, B.; Gross, R.E.; Moore, C.I.; Hochgeschwender, U. Combined Optogenetic and Chemogenetic Control of Neurons. Methods Mol. Biol. 2016, 1408, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forcelli, P.A. Applications of optogenetic and chemogenetic methods to seizure circuits: Where to go next? J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 95, 2345–2356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Chen, D.; Sweeney, P.; Yang, Y. An excitatory ventromedial hypothalamus to paraventricular thalamus circuit that suppresses food intake. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viskaitis, P.; Irvine, E.E.; Smith, M.A.; Choudhury, A.I.; Alvarez-Curto, E.; Glegola, J.A.; Hardy, D.G.; Pedroni, S.M.A.; Paiva Pessoa, M.R.; Fernando, A.B.P.; et al. Modulation of SF1 Neuron Activity Coordinately Regulates Both Feeding Behavior and Associated Emotional States. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 3559–3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunwar, P.S.; Zelikowsky, M.; Remedios, R.; Cai, H.; Yilmaz, M.; Meister, M.; Anderson, D.J. Ventromedial hypothalamic neurons control a defensive emotion state. Elife 2015, 4, e06633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckener, T.; Hess, S.; Belgardt, B.F.; Paeger, L.; Verhagen, L.A.W.; Husch, A.; Sohn, J.W.; Hampel, B.; Dhillon, H.; Zigman, J.M.; et al. High-fat feeding promotes obesity via insulin receptor/PI3K-dependent inhibition of SF-1 VMH neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2011, 14, 911–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coutinho, E.A.; Okamoto, S.; Ishikawa, A.W.; Yokota, S.; Wada, N.; Hirabayashi, T.; Saito, K.; Sato, T.; Takagi, K.; Wang, C.C.; et al. Activation of SF1 neurons in the ventromedial hypothalamus by DREADD technology increases insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. Diabetes 2017, 66, 2372–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaventura, J.; Eldridge, M.A.G.; Hu, F.; Gomez, J.L.; Sanchez-Soto, M.; Abramyan, A.M.; Lam, S.; Boehm, M.A.; Ruiz, C.; Farrell, M.R.; et al. High-potency ligands for DREADD imaging and activation in rodents and monkeys. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flak, J.N.; Goforth, P.B.; Dell’Orco, J.; Sabatini, P.V.; Li, C.; Bozadjieva, N.; Sorensen, M.; Valenta, A.; Rupp, A.; Affinati, A.H.; et al. Ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus neuronal subset regulates blood glucose independently of insulin. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 2943–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, W.P.; Sherwin, R.S.; During, M.J.; Borg, M.A.; Shulman, G.I. Local ventromedial hypothalamus glucopenia triggers counterregulatory hormone release. Diabetes 1995, 44, 180–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borg, M.A.; Borg, W.P.; Tamborlane, W.V.; Brines, M.L.; Shulman, G.I.; Sherwin, R.S. Chronic hypoglycemia and diabetes impair counterregulation induced by localized 2-deoxy-glucose perfusion of the ventromedial hypothalamus in rats. Diabetes 1999, 48, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meek, T.H.; Nelson, J.T.; Matsen, M.E.; Dorfman, M.D.; Guyenet, S.J.; Damian, V.; Allison, M.B.; Scarlett, J.M.; Nguyen, H.T.; Thaler, J.P.; et al. Functional identification of a neurocircuit regulating blood glucose. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, E2073–E2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Q.; Ye, C.P.; McCrimmon, R.J.; Dhillon, H.; Choi, B.; Kramer, M.D.; Yu, J.; Yang, Z.; Christiansen, L.M.; Lee, C.E.; et al. Synaptic Glutamate Release by Ventromedial Hypothalamic Neurons Is Part of the Neurocircuitry that Prevents Hypoglycemia. Cell Metab. 2007, 5, 383–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisbett, R.E. Hunger, obesity, and the ventromedial hypothalamus. Psychol. Rev. 1972, 79, 433–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avrith, D.; Mogenson, G.J. Reversible hyperphagia and obesity following intracerebral microinjections of colchicine into the ventromedial hypothalamus of the rat. Brain Res. 1978, 153, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bingham, N.C.; Verma-Kurvari, S.; Parada, L.F.; Parker, K.L. Development of a steroidogenic factor 1/Cre transgenic mouse line. Genesis 2006, 44, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Dhillon, H.; Yin, H.; Yoshimura, A.; Lowell, B.B.; Maratos-Flier, E.; Flier, J.S. Selective inactivation of Socs3 in SF1 neurons improves glucose homeostasis without affecting body weight. Endocrinology 2008, 149, 5654–5661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, A.; Kablan, A.; Yao, C.; Ho, T.; Podyma, B.; Weinstein, L.S.; Chen, M. Gsα deficiency in the ventromedial hypothalamus enhances leptin sensitivity and improves glucose homeostasis in mice on a high-fat diet. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bence, K.K.; Delibegovic, M.; Xue, B.; Gorgun, C.Z.; Hotamisligil, G.S.; Neel, B.G.; Kahn, B.B. Neuronal PTP1B regulates body weight, adiposity and leptin action. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 917–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiappini, F.; Catalano, K.J.; Lee, J.; Peroni, O.D.; Lynch, J.; Dhaneshwar, A.S.; Wellenstein, K.; Sontheimer, A.; Neel, B.G.; Kahn, B.B. Ventromedial hypothalamus-specific Ptpn1 deletion exacerbates diet-induced obesity in female mice. J. Clin. Investig. 2014, 124, 3781–3792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senn, S.S.; Le Foll, C.; Whiting, L.; Tarasco, E.; Duffy, S.; Lutz, T.A.; Boyle, C.N. Unsilencing of native LepRs in hypothalamic SF1 neurons does not rescue obese phenotype in LepR-deficient mice. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2019, 317, R451–R460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minokoshi, Y.; Haque, M.S.; Shimazu, T. Microinjection of leptin into the ventromedial hypothalamus increases glucose uptake in peripheral tissues in rats. Diabetes 1999, 48, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meek, T.H.; Matsen, M.E.; Dorfman, M.D.; Guyenet, S.J.; Damian, V.; Nguyen, H.T.; Taborsky, G.J.; Morton, G.J. Leptin action in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus is sufficient, but not necessary, to normalize diabetic hyperglycemia. Endocrinology 2013, 154, 3067–3076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, G.H.M.; Li, W.; Garcia, A.V.C.G.; Figueiredo, M.S.; Bjørbæk, C. Hypothalamic agouti-related peptide neurons and the central melanocortin system are crucial mediators of leptin’s antidiabetic actions. Cell Rep. 2014, 7, 1093–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Air, E.L.; Benoit, S.C.; Blake Smith, K.A.; Clegg, D.J.; Woods, S.C. Acute third ventricular administration of insulin decreases food intake in two paradigms. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2002, 72, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jauch-Chara, K.; Friedrich, A.; Rezmer, M.; Melchert, U.H.; Scholand-Engler, H.G.; Hallschmid, M.; Oltmanns, K.M. Intranasal insulin suppresses food intake via enhancement of brain energy levels in humans. Diabetes 2012, 61, 2261–2268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, J.W.; Oh, Y.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, S.; Williams, K.W.; Elmquist, J.K. Leptin and insulin engage specific PI3K subunits in hypothalamic SF1 neurons. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 669–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, A.W.; Kaelin, C.B.; Takeda, K.; Akira, S.; Schwartz, M.W.; Barsh, G.S. PI3K integrates the action of insulin and leptin on hypothalamic neurons. J. Clin. Investig. 2005, 115, 951–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hill, J.W.; Fukuda, M.; Gautron, L.; Sohn, J.W.; Kim, K.W.; Lee, C.E.; Choi, M.J.; Lauzon, D.A.; Dhillon, H.; et al. PI3K signaling in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus is required for normal energy homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujikawa, T.; Choi, Y.H.; Yang, D.J.; Shin, D.M.; Donato, J.; Kohno, D.; Lee, C.E.; Elias, C.F.; Lee, S.; Kim, K.W. P110β in the ventromedial hypothalamus regulates glucose and energy metabolism. Exp. Mol. Med. 2019, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.W.; Donato, J.; Berglund, E.D.; Choi, Y.H.; Kohno, D.; Elias, C.F.; DePinho, R.A.; Elmquist, J.K. FOXO1 in the ventromedial hypothalamus regulates energy balance. J. Clin. Investig. 2012, 122, 2578–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Nedungadi, T.P.; Zhu, L.; Sobhani, N.; Irani, B.G.; Davis, K.E.; Zhang, X.; Zou, F.; Gent, L.M.; Hahner, L.D.; et al. Distinct hypothalamic neurons mediate estrogenic effects on energy homeostasis and reproduction. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 453–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa, S.M.; Newstrom, D.W.; Warne, J.P.; Flandin, P.; Cheung, C.C.; Lin-Moore, A.T.; Pierce, A.A.; Xu, A.W.; Rubenstein, J.L.; Ingraham, H.A. An estrogen-responsive module in the ventromedial hypothalamus selectively drives sex-specific activity in females. Cell Rep. 2015, 10, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M.P.; Ameroso, D.; Meng, A.; Rock, A.; Maguire, J.; Rios, M. Essential and sex-specific effects of mGluR5 in ventromedial hypothalamus regulating estrogen signaling and glucose balance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19566–19577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furigo, I.C.; de Souza, G.O.; Teixeira, P.D.S.; Guadagnini, D.; Frazão, R.; List, E.O.; Kopchick, J.J.; Prada, P.O.; Donato, J. Growth hormone enhances the recovery of hypoglycemia via ventromedial hypothalamic neurons. FASEB J. 2019, 33, 11909–11924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seoane-Collazo, P.; Roa, J.; Rial-Pensado, E.; Liñares-Pose, L.; Beiroa, D.; Ruíz-Pino, F.; López-González, T.; Morgan, D.A.; Pardavila, J.Á.; Sánchez-Tapia, M.J.; et al. SF1-Specific AMPKα1 Deletion Protects Against Diet-Induced Obesity. Diabetes 2018, db171538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadori, G.; Fujikawa, T.; Anderson, J.; Berglund, E.D.; Frazao, R.; Michán, S.; Vianna, C.R.; Sinclair, D.A.; Elias, C.F.; Coppari, R. SIRT1 deacetylase in SF1 neurons protects against metabolic imbalance. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsted, J.A.; Chien, C.H.; Wang, D.; Panessiti, M.; Ameroso, D.; Greenberg, A.; Feng, G.; Kong, D.; Rios, M. Alpha2delta-1 in SF1+ Neurons of the Ventromedial Hypothalamus Is an Essential Regulator of Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis. Cell Rep. 2017, 21, 2737–2747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsted, J.A.; Meng, A.; Ameroso, D.; Rios, M. Sex-specific Effects of a2d-1 in the Ventromedial Hypothalamus of Female Mice Controlling Glucose and Lipid Balance. Endocrinology 2020, 161, bqaa068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinal, P.; André, C.; Quarta, C.; Bellocchio, L.; Clark, S.; Elie, M.; Leste-Lasserre, T.; Maitre, M.; Gonzales, D.; Cannich, A.; et al. CB1cannabinoid receptor in SF1-expressing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus determines metabolic responses to diet and leptin. Mol. Metab. 2014, 3, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coupé, B.; Leloup, C.; Asiedu, K.; Maillard, J.; Pénicaud, L.; Horvath, T.L.; Bouret, S.G. Defective autophagy in Sf1 neurons perturbs the metabolic response to fasting and causes mitochondrial dysfunction. Mol. Metab. 2021, 47, 101186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, C.; Kim, J.D.; Impellizzeri, D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Liu, Z.W.; Diano, S. UCP2 Regulates Mitochondrial Fission and Ventromedial Nucleus Control of Glucose Responsiveness. Cell 2016, 164, 872–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.S.; Yang, D.J.; Kinyua, A.W.; Yoon, S.G.; Seong, J.K.; Kim, J.; Moon, S.J.; Shin, D.M.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, K.W. Ventromedial hypothalamic primary cilia control energy and skeletal homeostasis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minokoshi, Y.; Alquier, T.; Furukawa, N.; Kim, Y.-B.; Lee, A.; Xue, B.; Mu, J.; Foufelle, F.; Ferré, P.; Birnbaum, M.J.; et al. AMP-kinase regulates food intake by responding to hormonal and nutrient signals in the hypothalamus. Nature 2004, 428, 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, M.; Varela, L.; Vázquez, M.J.; Rodríguez-Cuenca, S.; González, C.R.; Velagapudi, V.R.; Morgan, D.A.; Schoenmakers, E.; Agassandian, K.; Lage, R.; et al. Hypothalamic AMPK and fatty acid metabolism mediate thyroid regulation of energy balance. Nat. Med. 2010, 16, 1001–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- López, M.; Nogueiras, R.; Tena-Sempere, M.; Diéguez, C. Hypothalamic AMPK: A canonical regulator of whole-body energy balance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2016, 12, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Claret, M.; Smith, M.A.; Batterham, R.L.; Selman, C.; Choudhury, A.I.; Fryer, L.G.D.; Clements, M.; Al-Qassab, H.; Heffron, H.; Xu, A.W.; et al. AMPK is essential for energy homeostasis regulation and glucose sensing by POMC and AgRP neurons. J. Clin. Investig. 2007, 117, 2325–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Sánchez, N.; Seoane-Collazo, P.; Contreras, C.; Varela, L.; Villarroya, J.; Rial-Pensado, E.; Buqué, X.; Aurrekoetxea, I.; Delgado, T.C.; Vázquez-Martínez, R.; et al. Hypothalamic AMPK-ER Stress-JNK1 Axis Mediates the Central Actions of Thyroid Hormones on Energy Balance. Cell Metab. 2017, 26, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quenneville, S.; Labouèbe, G.; Basco, D.; Metref, S.; Viollet, B.; Foretz, M.; Thorens, B. Hypoglycemia-sensing neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus require AMPK-induced TXN2 expression but are dispensable for physiological counterregulation. Diabetes 2020, 69, 2253–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coppari, R. Metabolic actions of hypothalamic SIRT1. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 23, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco-Solis, R.; Ramadori, G.; Coppari, R.; Sassone-Corsi, P. SIRT1 relays nutritional inputs to the circadian clock through the Sf1 neurons of the ventromedial hypothalamus. Endocrinology 2015, 156, 2174–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orozco-Solis, R.; Aguilar-Arnal, L.; Murakami, M.; Peruquetti, R.; Ramadori, G.; Coppari, R.; Sassone-Corsi, P. The circadian clock in the ventromedial hypothalamus controls cyclic energy expenditure. Cell Metab. 2016, 23, 467–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadori, G.; Fujikawa, T.; Fukuda, M.; Anderson, J.; Morgan, D.A.; Mostoslavsky, R.; Stuart, R.C.; Perello, M.; Vianna, C.R.; Nillni, E.A.; et al. SIRT1 deacetylase in POMC neurons is required for homeostatic defenses against diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab. 2010, 12, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Hendrich, J.; Van Minh, A.T.; Wratten, J.; Douglas, L.; Dolphin, A.C. Functional biology of the α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2007, 28, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, Ç.; Allen, N.J.; Susman, M.W.; O’Rourke, N.A.; Park, C.Y.; Özkan, E.; Chakraborty, C.; Mulinyawe, S.B.; Annis, D.S.; Huberman, A.D.; et al. Gabapentin Receptor α2δ-1 Is a Neuronal Thrombospondin Receptor Responsible for Excitatory CNS Synaptogenesis. Cell 2009, 139, 380–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garfield, A.S.; Shah, B.P.; Madara, J.C.; Burke, L.K.; Patterson, C.M.; Flak, J.; Neve, R.L.; Evans, M.L.; Lowell, B.B.; Myers, M.G.; et al. A parabrachial-hypothalamic cholecystokinin neurocircuit controls counterregulatory responses to hypoglycemia. Cell Metab. 2014, 20, 1030–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.W.; Jo, Y.H.; Zhao, L.; Stallings, N.R.; Chua, S.C.; Parker, K.L. Steroidogenic factor 1 regulates expression of the cannabinoid receptor 1 in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus. Mol. Endocrinol. 2008, 22, 1950–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabelo, C.; Hernandez, J.; Chang, R.; Seng, S.; Alicea, N.; Tian, S.; Conde, K.; Wagner, E.J. Endocannabinoid signaling at hypothalamic steroidogenic factor-1/proopiomelanocortin synapses is sex-and diet-sensitive. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebato, C.; Uchida, T.; Arakawa, M.; Komatsu, M.; Ueno, T.; Komiya, K.; Azuma, K.; Hirose, T.; Tanaka, K.; Kominami, E.; et al. Autophagy Is Important in Islet Homeostasis and Compensatory Increase of Beta Cell Mass in Response to High-Fat Diet. Cell Metab. 2008, 8, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Goldman, S.; Baerga, R.; Zhao, Y.; Komatsu, M.; Jin, S. Adipose-specific deletion of autophagy-related gene 7 (atg7) in mice reveals a role in adipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 19860–19865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coupé, B.; Ishii, Y.; Dietrich, M.O.; Komatsu, M.; Horvath, T.L.; Bouret, S.G. Loss of autophagy in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons perturbs axon growth and causes metabolic dysregulation. Cell Metab. 2012, 15, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quan, W.; Kim, H.K.; Moon, E.Y.; Kim, S.S.; Choi, C.S.; Komatsu, M.; Jeong, Y.T.; Lee, M.K.; Kim, K.W.; Kim, M.S.; et al. Role of hypothalamic proopiomelanocortin neuron autophagy in the control of appetite and leptin response. Endocrinology 2012, 153, 1817–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushik, S.; Rodriguez-Navarro, J.A.; Arias, E.; Kiffin, R.; Sahu, S.; Schwartz, G.J.; Cuervo, A.M.; Singh, R. Autophagy in hypothalamic agrp neurons regulates food intake and energy balance. Cell Metab. 2011, 14, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternson, S.M.; Shepherd, G.M.G.; Friedman, J.M. Topographic mapping of VMH → arcuate nucleus microcircuits and their reorganization by fasting. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1356–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raefsky, S.M.; Mattson, M.P. Adaptive responses of neuronal mitochondria to bioenergetic challenges: Roles in neuroplasticity and disease resistance. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2017, 102, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hass, D.T.; Barnstable, C.J. Mitochondrial uncoupling protein 2 knock-out promotes mitophagy to decrease retinal ganglion cell death in a mouse model of glaucoma. J. Neurosci. 2019, 39, 3582–3596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, J.; Patisaul, H.B. Sexually dimorphic expression of hypothalamic estrogen receptors α and β and Kiss1 in neonatal male and female rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 2011, 519, 2954–2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santiago, A.M.; Clegg, D.J.; Routh, V.H. Estrogens modulate ventrolateral ventromedial hypothalamic glucose-inhibited neurons. Mol. Metab. 2016, 5, 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheung, C.C.; Krause, W.C.; Edwards, R.H.; Yang, C.F.; Shah, N.M.; Hnasko, T.S.; Ingraham, H.A. Sex-dependent changes in metabolism and behavior, as well as reduced anxiety after eliminating ventromedial hypothalamus excitatory output. Mol. Metab. 2015, 4, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canteras, N.S.; Simerly, R.B.; Swanson, L.W. Organization of projections from the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus: A Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin study in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994, 348, 41–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krieger, M.S.; Conrad, L.C.; Pfaff, D.W. An autoradiographic study of the efferent connections of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1979, 183, 785–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; O’Malley, B.W.; Elmquist, J.K. Brain nuclear receptors and body weight regulation. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1172–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Dai, Z.; Yang, D.; Gao, D.; Shao, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Z.; et al. A GABAergic neural circuit in the ventromedial hypothalamus mediates chronic stress–induced bone loss. J. Clin. Investig. 2020, 130, 6539–6554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Type of Target | Target | Mice Model Name | Sex | Challenge | BW | FI | EE | Adiposity | Glycemia | Glucose Tolerance | Insulin Sensitivity |

Leptin Sensitivity | SNS Activity | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hormone receptors and related signaling pathways | LEPR | Sf1-Cre, Leprflox/flox | M | SD | ↑ | n.s. | n.s. | ↑ | n.s. | - | - | - | - | [23][20] |

| HFD | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | n.s. | - | - | - | - | |||||

| SOCS3 | Sf1-Cre, Socs3flox/flox | M | SD | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | [25][37] | |

| HF-HS | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | |||||

| Leptin (a) | ↓ | ↓ | - | - | - | - | - | ↑ | - | |||||

| Gsα | VMHGsKO | M (b) | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | [26][38] | |

| HFD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | |||||

| PTP1B | Sf1-Ptpn1−/− | F | HFD | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | - | - | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | [27][39] | |

| M | HFD | n.s. | - | - | n.s. | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| IR | SF-1ΔIR | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | - | - | - | - | [28][26] | ||

| HFD | ↓ | ↓ | n.s. | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | |||||

| p110α | p110αlox/lox/SF1-Cre | M | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | ↓ | - | [29][49] | |

| HFD | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | - | |||||

| p110β | p110β KOsf1 | M | SD | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ BAT th.(c) | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | - | [30][50] | |

| HFD | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | |||||

| FOXO1 | Foxo1 KOSf1 | M | SD | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↓ | - | - | - | - | - | [31][51] | |

| F | SD | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↓ | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| M | HFD | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | - | ||||

| ERα | ERαlox/lox/SF1-Cre | F | SD | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | - | - | - | [32][52] | |

| F | HFD | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | - | - | - | - | ↓ | ||||

| Nutrient sensors | AMPK | SF1-Cre AMPKα1flox/flox | M | SD | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↓ | - | - | - | - | ↑ (d) | [33][56] |

| M | HFD | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | n.s. | - | - | ||||

| SIRT1 | Sf1-Cre; Sirt1loxP/loxP | M/F | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | - | - | - | [34][57] | |

| HFD | ↑ | n.s. | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | - | |||||

| Glutamatergic neurotransmission and synaptic receptors | VGLUT2 | Sf1-Cre; Vglut2flox/flox | M/F | SD | n.s. | - | - | - | ↓ | - | - | - | - | [20][33] |

| M/F | HFD | ↑ | ↑ | n.s. | ↑ | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| mGluR5 | mGluR52L/2L:SF1-Cre | F | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | ↓ | [35][54] | |

| M | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ||||

| M/F | HFD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | - | - | - | - | - | ||||

| α2δ-1 | α2δ-12L/2L:SF1-Cre | M | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | ↓ | [36][37][58,59] | |

| M | HFD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | - | - | ||||

| F | SD | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | - | |||||

| F | HFD | ↑ | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | n.s. | ↓ | ↓ | - | ↑ | ||||

| CB1 | SF1-CB1-KO | M | SD | n.s. | n.s. | ↑ BAT th. | ↓ | n.s. | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | [38 |