The journey of the Andean crop quinoa (Chenopodium quinoa Willd.) to unfamiliar environments and the combination of higher temperatures, sudden changes in weather, intense precipitation, and reduced water in the soil has increased the risk of observing new and emerging diseases associated with this crop. Several diseases of quinoa have been reported in the last decade. These include Ascochyta caulina, Cercospora cf. chenopodii, Colletotrichum nigrum, C. truncatum, and Pseudomonas syringae. The taxonomy of other diseases remains unclear or is characterized primarily at the genus level. Symptoms, microscopy, and pathogenicity, supported by molecular tools, constitute accurate plant disease diagnostics in the 21st century. This review aims to compile the existing information and make accurate associations between specific symptoms and causal agents of disease. In addition, we place an emphasis on downy mildew and its phenotyping, as it continues to be the most economically important and studied disease affecting quinoa worldwide.

- causal agents

- downy mildew

- pathogenicity

- resistance factors

- severity

- quinoa diseases

- quinoa disease assessment

1. Introduction

Agriculture is affected by global climate change. Non-traditional crops with high nutritional value and the ability to cope with abiotic stress are of special interest in today’s world. The recent introduction and cultivation of quinoa in novel environments has resulted in a wider spectrum and higher intensity of infectious diseases. Oomycetes and fungi are the two most important eukaryotic plant pathogens [1]; their predominance on the quinoa pathobiome is also evident.

However, an update is necessary because new emerging diseases of the quinoa mycobiome are being discovered. Taxonomy based on the morphological characteristics and nomenclature of fungi is relatively conserved and informative when high-level classifications (genus level) are considered. However, there is uncertainty when lower-level phylogenies (species level) are considered due to the fast-evolving traits and phenotypic plasticity of fungi [2][7]. As a result, DNA and molecular sequence-database comparisons techniques have been employed, along with various DNA fingerprinting and more advanced and complex methods such as whole-genome sequencing, for the identification of plant pathogens [3][4][8,9].

In addition to ITS, various other markers exist for multi-locus sequencing. It is commonly used by combining ITS with other relevant genomic regions (e.g., COX I, calmodulin, and TEF1 gene regions). It has proven helpful and necessary for the accurate identification of microbial plant pathogens [5][6][7][11,12,13]. Such molecular approaches should be paired with pathogenicity assessments, including the description of disease symptoms, isolation and artificial inoculation of quinoa tissue, recording of symptoms, and re-isolation.

This review aims to provide an updated overview of microbial plant pathogens causing disease in quinoa, focusing on the morphological characterization and molecular identification of the causal agents. Research carried out in the Andean countries some decades ago provides insightful and valuable reports, described herein. We compiled and analyzed existing information, with a marked emphasis on downy mildew.

2. Downy Mildew of Quinoa

The genus Peronospora belongs to the Peronosporaceae family (Peronosporales order), which are highly physiologically specialized, biotrophic organisms. Phytopathogenic oomycetes are eukaryotic microbes with filamentous vegetative growth and spores for reproduction (fungus-like). Molecular analysis revealed they are among the Stramenopiles (or heterokont), closely related to golden-brown algae and diatoms [1][8][9][10][1,18,19,20]. Fundamental features are: Oomycetes cell walls are mostly composed of glucans, in contrast to chitin from fungi [11][14]. Most oomycetes are insensitive to azole fungicides (e.g., ketoconazole) because they do not have the ergosterol pathway needed to activate the azole-fungicide mode of action [12][13][14][21,22,23]. During their vegetative state, oomycetes are diploid compared to haploid or dikaryotic fungi [1].

Due to taxonomic confusion, downy mildew was previously classified as Peronospora farinosa and considered as such by most studies for about 50 years [15][16][17][24,25,26]. Byford (1967a,b) [18][19][27,28] investigated cross-inoculation experiments and concluded the division of three formae speciales (f. spp.) Table 1.

| Host (Genus/Species) | Pathogen Current Identity |

Byford Classification (f. spp.) | P. farinosa formae speciales |

|---|

| Beta | spp. | P. schachtii [17] | [26] | P. farinosa | f. sp. | betae |

| C. álbum + C. quinoa | P. variabilis [20][21] | [29,30] | P. farinosa | f. sp. | chenopodii | |

| Spinacia | oleracea | P. effusa [22][23] | [33,34] | P. farinosa | f. sp. | spinaciae |

Later, a phylogenetic study on P. variabilis of C. quinoa and C. album from different geographical regions showed that both are located in the same phylogenetic cluster with no evidence to separate them into different taxa [20][21][24][25][29,30,31,32]. (fig leave goosefoot) [7][13], P. chenopodii-polyspermi to C. polyspermum L. (many-seeded goosefoot), and P.schachtii to sugar beet [17][26]. In older literature, P. farinosa was used as the causal agent of downy mildew of quinoa.

The earliest report of downy mildew infecting quinoa in South America came from Martin Cardenas (1941), who found it infecting quinoa in Cochabamba, Bolivia, and identified it as P. farinosa. It is expected to become ubiquitous in all quinoa cropping areas as oospores found in seeds have also been seen in old dried leaves [25][26][27][32,53,54]. (fig leaf goosefoot), were reported to harbor the pathogen based on morphological identification [28][29][30][39,45,57] and molecular COX2 bar coding for C. berlandieri var macrocalycium (Table 2). These reports require further investigation to confirm the accurate identity of the pathogen.

| Country | C. quinoa | Leaves (√), Seed (x) |

C.album | Leaves |

C. berlandieri | var. Macrocalycium |

C. murale | Leaves |

C. ambrosoides | Leaves |

C. ficifolium | Leaves |

Researcher | Year | [Ref] | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mor. | Mol. | Mor. | Mol. | Mor. | Mol. | Mor. | Mol. | Mor. | Mol. | Mor. | Mol. | ||||||||||||||||

| Bolivia | √ | Martin Cardenas | 1941 | [31] | [36] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peru | √ | G. Garcia | 1947 | [32] | [37] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Canada | √ | JF.Tewari | 1990 | [33] | [38] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Peru | √ | √ | √ | √ | L.Aragon | 1992 | [28] | [39] | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ecuador | √ | Jose Ochoa | 1999 | [34] | [40] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Denmark | √ | S. Danielsen | 2002 | [35] | [41] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Poland | √ | Panka | 2004 | [36] | [42] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| India | √ | A. Kumar | 2006 | [37] | [43] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bolivia | √ | √ | Erica Swenson | 2006 | [38] | [44] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Argentina | √ | √ | Y.J. Choi | 2008 | [17] | [26] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| China | √ | √ | 2010 | [20] | [29] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ireland | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| South Korea | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Netherlands | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Germany | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Latvia | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Romania | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Italy | √ | √ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

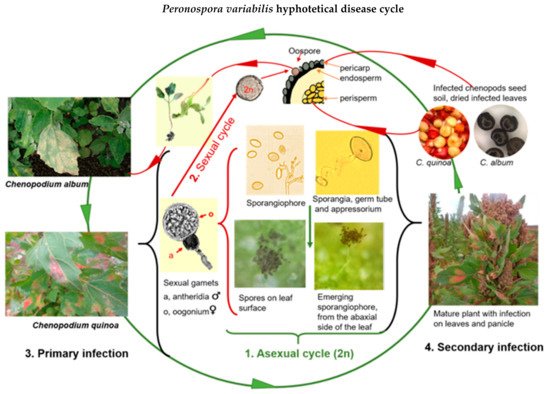

Based on various scientific studies, we assembled a hypothetical disease cycle for P. variabilis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Proposed disease cycle of quinoa downy mildew caused by Peronospora variabilis (Photos: C. Colque-Little). Picture of haploid gamets adapted from Judelson [39][58].

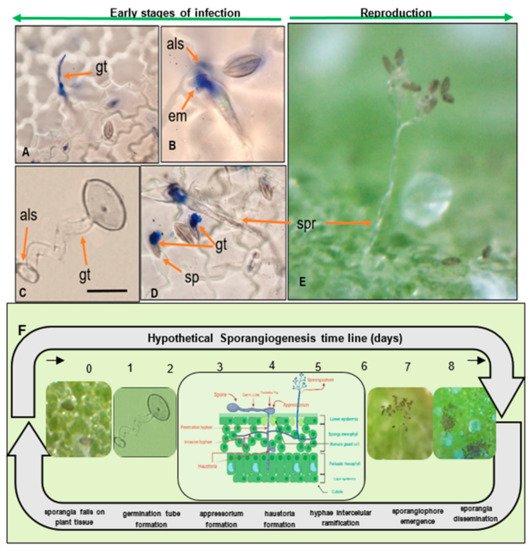

When mature sporangia fall on compatible leaf tissue with free moisture and relative humidity (more than 85%), the infection begins. Spores from pathogenic oomycetes produce an adhesive vesicle on the spore side in contact with the host (ventral) at early infection stages In most downy mildews, the hyphae enter the leaf via stomatal pores [39][58] The formation of an appressorium-like swelling (penetration structures that exert pressure) on histopathological samples was observed under a microscope [40][41][52,59].

Once an appressorium is established, the secretion of extracellular matrices during the germination of the sporangia appears, as reported elsewhere (Figure 3B) [41][59]. Seven to ten days after the primary infection, sporangia are disseminated to other leaves by wind and water [34][41][40,59] In general, Peronospora species require moderate temperatures (10 °C–20 °C) for optimal sporulation [42][43][63,64]. While the disease is developing, several asexual cycles (reproduction of sporangia) may occur.

Figure 3. Quinoa leaf infections caused by P. variabilis sporangiogenesis during the early stages of asexual reproduction. (A) Sporangium forming germ tube (gt) and faint penetration hyphae towards the mesophyll. (B) Extracellular matrices (em) secreted from germinating sporangium (sp) and appressorium-like (als) structure penetrating stomata. (C) Sporangium, forming germ-tube (gt) and appressorium like structure in water. (D) Sporangiophore (spr) emerging from stomata. (E) Sporangiophore holding sporangia, emerging from lower epidermis. Scale bar: 20 µm. (F) Hypothetical P. variabilis sporangiogenesis timeline (Photos: C. Colque-Little). Illustration in timeline created with Biorender.com.

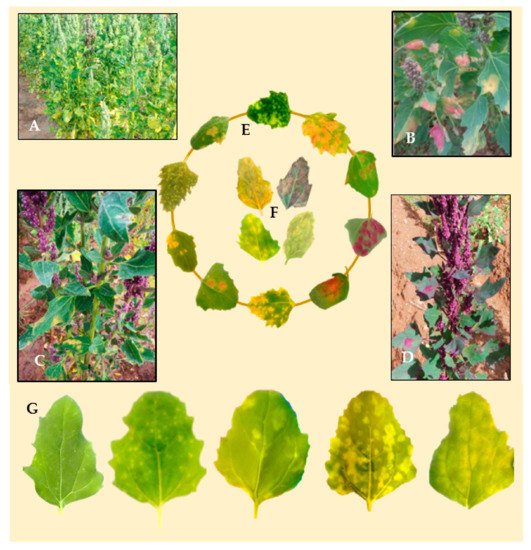

Infected leaf tissue manifests lesions and signs on both sides of the leaf. Symptoms on infected plants vary depending on genotype, growth stage, and environmental conditions (Figure 4A–D). Classic symptoms include pale or yellow chlorotic lesions on the leaf surface (Figure 3E) and dark gray-violaceous sporulating areas, mostly on the lower surface (Figure 3F). The lesions can be several and small in some cultivars, whereas in others the lesions are extensive, diffuse, and irregular (Figure 4G).

Figure 4. (A) Quinoa crop severely damaged by downy mildew. (B–D). Infected varieties in the fields of the main quinoa growing areas of Bolivia. (E) Adaxial leaf side belonging to different quinoa genotypes artificially infected with downy mildew. (F) Abaxial side of the leaves showing sporulation. (G) Differences in disease symptoms, ranging from hypersensitive reactions causing pale yellowish spots (left) to high susceptibility with chlorotic lesions covering the whole leaf (right) (Photos: C. Colque-Little).

Downy mildew primarily affects the foliage, but it is possible to find it colonizing different organs and tissues of quinoa plants. Taha (2019) gathered a composite of quinoa seedlings at different growth stages, subdivided them into different organs, and detected P. variabilis DNA on 0.8% of the root samples, 83% on the cotyledon and leaf, and 42% on steam samples. Since the pathogen was detected at early and late growth stages of the quinoa plant, it was thought to present a systemic mode of infection [68]. However, other researchers argue [69] that the germinated oospores-mycelium spreads through intercellular parenquimatic spaces (next to xylem but not wood vessels) of the hypocotyl acropetally, towards the plant’s aerial parts, and is finally inserted into the developing seed.

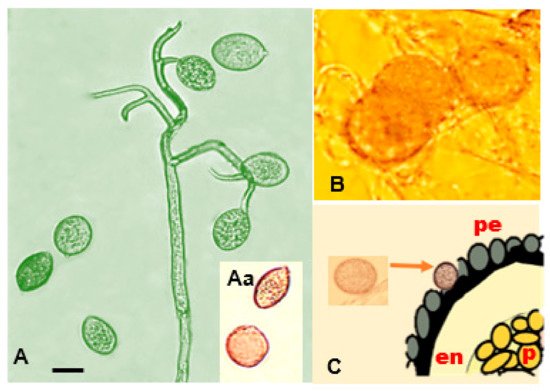

Peronospora variabilis hyphae are coenocytic (hyphae without septae) and multinucleate, resulting from nuclear divisions within the cell without an accompanying division of the cytoplasm (cytokinesis). Sporangiophores are 240–580 µm long, slender, arborescent, dichotomously ramified five to six times in a sharp angle, ending in two to three straight to slightly curved branches (Figure 5A). Taxonomic measurements such as spore lengths and widths can vary depending on the homogeneity of the conidium population, the origin of the isolates, the spore subpopulation, or different roles or times in the pathogen’s life history [44][70]. this variability from measurements taken by various researchers [17][20][24][45][46][47][48][27][49][26,29,31,46,47,49,51,54,72] and the average of their measurements is provided as a reference (Figure 5B,D).

It has been reported to be heterothallic and requires two compatible partners for oospore formation (mating). When eight single-lesion isolates coming from different regions of Peru and Bolivia were crossed in all possible combinations using a detached leaf assay, the existence of two mating types, P1 and P2, was apparent [50][73]. [51][69] and have the appearance of swollen hyphal tips [52][74]. The combination of their lowered metabolism, thick wall, and lipid-rich cytoplasm make them effective resting structures.

(Figure 5 Aa,D). Oospores can survive inhospitable environments, such as freezing, desiccation, starvation, and microbial degradation [9][19]. They permit the completion of the pathogen life cycle and enhance its fitness by providing a mechanism for genetic variation [39][58]. (2019) hypothesize that oospores bearing tissues (cotyledons, leaves, and the perianths of seeds) shed during the life cycle of quinoa plants may play a role in the persistence of oospores in soil.

Danielsen and Ames (2004) [27][54] detected oospores in the pericarp (external tegument of the episperm) using ultra-microtome cuts (Figure 5F). El-Assiuty (a) (2019) confirmed their occurrence in examined seed samples, revealing a 90% presence in the perianth, 87% in the seed coat, 3% in the embryo, and 2% in the perisperm [26][53].

After planting the surface-sterilized seed of a downy mildew susceptible variety, the observations started. Oospores were present in the radicle-pith three days after germination, inside the cortex of hypocotyls, and in the mesophyll of cotyledons seven days after planting. They develop in the cortex tissue of juvenile seedlings 15 days post-planting [51][69]. This research is consistent with what has been found for other downy mildew diseases such asPlasmopara viticola, the mature oospores of which germinated for 3–7 days under a favorable regime of rainfall and temperature [53][76].

Moreover, oospores were detected in all tissues of quinoa plants that had been sown 45–120 days previously [26][51][53,69]. They were also seen on leaves of senescent infected plants, artificially inoculated with a single Danish isolate under greenhouse conditions, suggesting that the isolate had both mating types present (Figure 5E. Colque-Little, unpublished). In addition, they have been found in old infected leaves collected in Andean regions of quinoa production (Peru, Bolivia) [27][54] and fresh leaf tissue collected in Pennsylvania, USA [54][77].

Greenhouse experiments with oospore-infected seed samples sown in high and low relative humidity showed a significant difference in visible seedling infections among samples under high humidity and with a large oospore density in most cases. However, oospore density seems to be more critical for seedling infections when the relative humidity is low [55][56][57][75,78,79]. Briefly, the seed is soaked in water under agitation. Calixtro (2017) quantified the number of oospores present on susceptible seeds and found it was three times greater than the number on tolerant varieties demonstrating that host genotype is an important factor [58][82].

Peronospora variabilisis a genetically diverse group [21][30] with multiple population structures, in light of three facts:Chenopod hosts have a vast degree of genetic diversity and plasticity [59][60][83,84]. Peronospora variabilis has great adaptability (climatically and geographically), hence its worldwide geographic presence [27][54].The occurrence of sexual reproduction permits genotypic pathotype expansion [61][4].

Swenson (2006) collected 43 isolates from eight Bolivian regions [38][44]. A group of P. variabilis herbarium and isolates from different geographic locations (Argentina, Bolivia, Denmark, Ecuador, and Peru) were phylogenetically analyzed based on ITS rDNA sequences. In another study, researchers characterized 40 isolates fromP. variabilisoriginating in the Andean highlands (Peru and Ecuador) and Denmark (Jutland, Sealand) using universally primed PCR (UP-PCR) fingerprinting analysis. A separation between the Danish and Andean isolates in two distinctive clusters was found, together with genotypic variations between isolates within each cluster [21][30].

In the future, the next step might be the virulence profiling of P. variabilis, achieved through the sequencing of its genome, followed by transcriptomic analysis. Progress in genome sequencing technologies can provide genome data to better understand how microbes live, evolve, and adapt. The genomes of microbial pathogens can vary greatly in size and composition; this also includes when closely related species are considered. In the case of Peronospora, species greatly vary between 45.6 to 159.9 Mb when estimates are made using image analysis of nuclear Feulgen staining [62][85].

Another way to elucidate genotypic and phenotypic variation within pathogen populations is to use virulence-phenotypic assays with a standard set of differential hosts. Spinach downy mildew has such a set composed of 11 cultivars, maintained with the help of the international working group on P. effusa (IWGP) [63][64][65][86,87,88].

This organization invites researchers to use the set to identify new isolates that can later be nominated, tested for various criteria, and then given a race designation [63][64][65][86,87,88]. (1999) made the first step towards this from a collection of twenty P. variabilis isolates that corresponded to different Ecuatorian ecoregions [34][40]: An area where quinoa cultivation was not regularly practised. The least virulent strains were present here and were identified as virulence group 2 (V2).A region where landraces and newly released cultivars were introduced. Fields located where landraces and newly released cultivars have been cultivated for many years.

Ochoa et al, (1999) investigated seedlings under controlled environments from 60 selected genotypes and the above-mentioned P. variabilis collection; quinoa lines were selected for consistent compatible/incompatible reactions. Based on these results, four resistance factors (R1, R2, R3, and R4) were postulated [34][40]. The measurements of severity and sporulation of downy mildew from reference cultivars (Puno, Titicaca, and Vikinga) and many other genotypes used by Colque-Little et al. Therefore, we suggest that the presence of resistance factors could be preliminarily hypothesized on reference cultivars.

Age-related resistance becomes relevant for biotrophic pathogens, which require healthy plant tissue to complete their cycle. For the quinoa/downy mildew interaction, it has been demonstrated that disease incidence has a low heritability H2= 0.4 and a low correlation with severity and sporulation (0.67 and 0.65, respectively) To measure the area under the disease curve progression (AUDPC), a minimum record of three to four observations of disease severity is essential. A similar study has highlighted the importance of measuring the disease severity over time for other interactions, such as Phytophthora infestans infecting potatoes.

Calixtro (2017) recorded high variability in the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) within the same quinoa accession during different phenological stages. The higher AUDPC values were seen at 104 days after sowing with favorable disease conditions [58][82].

Therefore, we suggest assessing downy mildew as soon as the first symptoms of the disease are visible. The first reading could be when nine pairs of leaves (BBCH 1–1.9) have emerged or beforehand in cases where disease symptoms are visually observed. Vegetative cycle effects were also shown in another study that analyzed the mean-based cluster of inter-ecotype F2:6 population crosses and identified the following three clusters [66][67][68][48,95,96]: (a) Cluster one: consisting of late, mildew-resistant, high-yielding lines;(b) Cluster two: consisting of semi-late lines with intermediate yield and mildew : consisting of early to semi-late accessions with low yield and mildew susceptibility.

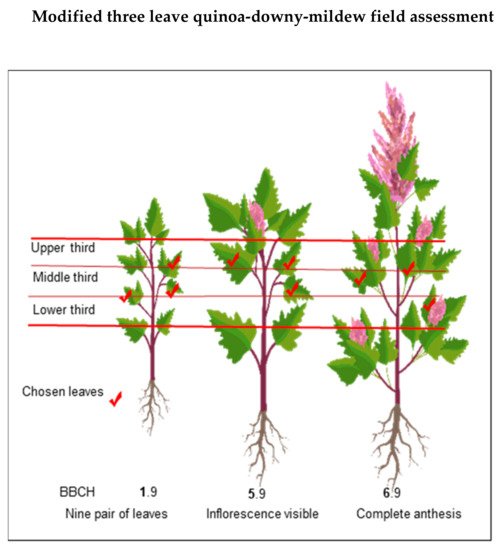

Danielsen and Munk [69][97] evaluated various field assessment methods to predict yield losses due to downy mildew. These responses might result from inducible plant defense responses, which occurs at the starting interaction site but also in distal, uninfected parts [70][71][72][99,100,101]. Avoid the lower and upper extremities of the plant because they are prone to senescence/defoliation [69][97] and plant defense responses, respectively. Next, estimate the percentage of affected leaf area using the attached scale [57][79] (Figure 9).

Figure 8. Modified from Danielsen and Munk (2004) [69][97]. Three-leaf field assessment method for quinoa-downy mildew at different growth stages.

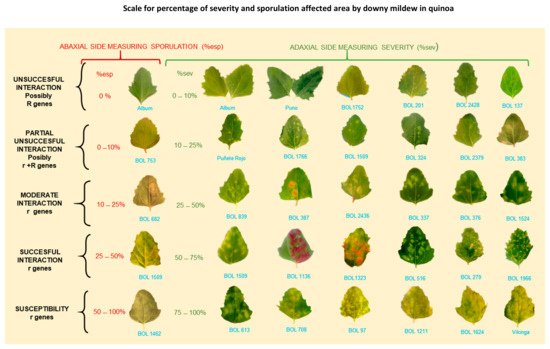

Figure 9. Scale for percentage of severity and sporulation area affected by downy mildew in quinoa. r = postulated minor genes; R = hypothesized major genes. BOL = accession numbers. Note: Percentage of sporulation is estimated on the abaxial leaf side area covered by visible lesion. It is not estimated on the total abaxial side leaf area (Colque-Little et al., 2021) [40][52]. Photos by Colque-Little.

The losses caused by downy mildew depend on the plant’s phenological phase at the time of infection and the amount of resistance that the cultivar has [73][102]. Infection of susceptible cultivars may result in severe yields losses if the pathogen has favorable weather conditions, particularly high relative humidity [27][54]. If the infection occurs in the plant’s initial growth stages, susceptible crops could completely fail; in less susceptible cultivars, the loss may fluctuate between 20% and 40% [61][4]. In a conventional intensive agriculture system of Cajamarca (Peru), between five to seven fungicide applications were needed to control the infection during the agricultural campaign [74][103].

-

tolerant crop varieties; and

-

cultural practices (options on the list below).

(a) Policymakers, smallholder farmers, and other stakeholders need resources for collective action for the establishment of a seed supply chain with quality standards (low levels of key seed-borne diseases). Experiences with complementary intervention such as capacity building and technical assistance have shown this influence in an appropriate conceptual model of sustainable production [75][104].

(b) The detection of P. variabilis on the seed is achieved using a simple method [25][27][32,54]. In the case of the presence of an oospore, treat the seed with a systemic fungicide [76][105]. For small samples, alternative treatments such as a hot water bath (50 °C–60 °C) could be considered for 10 to 30 min, as this method has been applied successfully to eradicate seed-borne pathogens of spinach [77][106].

(c) After or without treatment, the addition of beneficial microbes by priming the seed with products such as commercially available Trichoderma can enhance the growth of the plants [78][107].

(d) Avoiding excess water in the field;

(e) Implementing effective weed control, especially of alternate host C. album;

(f) Practicing crop rotation;

(g) Spraying the plants around 45 days after planting in areas with endemic infection as a preventive measure [51][69]. Use oomycete sensitive chemical control measures (e.g., Alietti) at principal growth stages, e.g., leaf development, inflorescence emergence, flowering, and fruit development [11][27][79][14,54,92]. Fungicides could be applied, alternating between systemic and contact products, starting with systemic products. Bio-pesticide or plant extracts could replace fungicides with a uniform and preventive application [80][5]. Inducers of resistance are an alternative [81][108].

Modified from Danielsen and Munk (2004) [69][97]. Three-leaf field assessment method for quinoa-downy mildew at different growth stages.

Scale for percentage of severity and sporulation area affected by downy mildew in quinoa. r = postulated minor genes; R = hypothesized major genes. Note: Percentage of sporulation is estimated on the abaxial leaf side area covered by visible lesion. It is not estimated on the total abaxial side leaf area (Colque-Little et al.

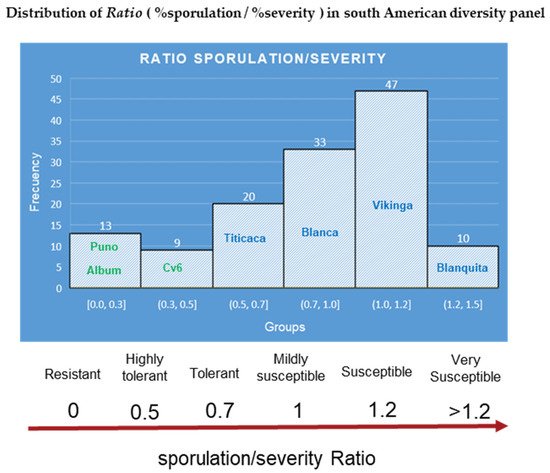

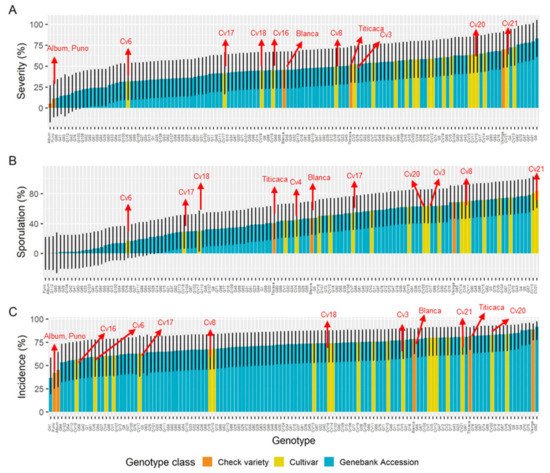

For agriculture, field or host resistance is still the most important way of controlling diseases because it leads to the most cost-effective ratio for the grower [82][83][84][109,110,111]. The response to downy mildew in a diversity panel of 132 quinoa genotypes resulted in strong phenotypic variation with high disease trait heritability (H2= 0.78 for severity,H2= 0.82 for sporulation). (2012) characterized the quinoa/downy mildew pathosystem in field experiments and discussed the presence of R-genes, multiple r genes, defeated R-genes, and combinations, with the most common interaction being that corresponding to field resistance [85][93]. For quinoa downy mildew, it was demonstrated that the variance for genotype-by-experiment interaction σ2 G E was large, reflecting that even minute environmental changes can trigger a genotype to respond differently to the disease (Figure 10) [40][52]. Furthermore, segregation in an F2 mapping population derived from a cross of saponin-free and bitter genotypes suggested that downy mildew resistance has a dominant inheritance [86][117].

Therefore, field phenotyping experiments of P. variabilisi nfections using diverse quinoa genotypes should include multiple environments and points in time. Using mixed modeling to detect quantitative trait loci (QTLs) by considering them as random samples from a population of target environments and time could be one alternative [87][118]. Under controlled conditions, it would make sense to use elite diversity panels with replicates, reference cultivars, and genetically diverse pathogen isolates in a series of experiments that are designed randomly.

The characterization of a south American panel demonstrated robust differences between the genotypes for all disease traits [40][52] Moreover, at least five cultivars that were released by Bolivian breeding programs [88][89][112,119], which included downy mildew tolerance, showed moderate to low severity and reduced the reproduction of the pathogen. Interestingly, the incidence (Figure 11A,C) and severity of cultivars 6, 17, and 18 might have classified them as susceptible, but their ability to prevent the pathogen from multiplying conferred them some degree of resistance This finding suggests that the scoring of both parameters in plantlets can contribute to better disease assessments of cultivars.

Therefore, we propose using the (R = % sporulation/% severity) ratio to better rate elite genotypes in breeding programs. Using the data set from a previous study [40][52], the ratio was calculated. Histograms separated the diversity panel into six groups and derived a ratio-based scale (Figure 10). The bimodal distribution displayed by the histograms is consistent with previous findings forP. variabilisfield interactions [38][44].

Figure 10. Ratio calculated from mean averages of sporulation/severity for the South American diversity panel. The names inside the histogram bars correspond to reference and representative cultivars for each group. Source: calculated with the data set from Colque-Little et al. (2021) [40][52].

Figure 11. Disease traits estimated means fitted on a generalized linear mixed model (GLMM) for a diversity panel, comprising gene bank accessions (landraces), cultivars (Bolivian-bred cultivars), and check varieties (reference cultivars). (A) Severity of infection, (B) sporulation, and (C) incidence of infection. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Adapted from Colque-Little et al. (2021) [40][52].

These regions have been classified according to their soil type, rainfall, and temperature as Northern, Central, Southern highlands, and Andean slopes (Table 6) [61][68][88][89][4,96,112,119]. The Andes have heterogenic topography; their altitude ranges between 3200 and 6500 m above sea level; hence, there are variations in temperature and humidity [90][120]. Indeed, temperature decreases at a rate of 0.7 °C for every 100-m increase in altitude in Chile’s Tarapaca region. Therefore the coastal Atacama littoral plains differ from mountain sites (e.g., Los Condores) which enjoy fog oases and lomas vegetation [91][121].

| Temperature | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eco-Region | Soil | Altitude m.a.s.l | Rainfall (mm) | Max. | Min. | Av. |

| Northern Highland shores of Lake Titicaca |

Rich in organic matter | 3500–4000 | 500 | 14 | 4 | 7 |

| Central Highland | Slightly acid | 3300–4100 | 350 | 17.7 | −2 | 8.7 |

| Southern Highland | Arid and poor soils | 3200–4000 | 50–200 | 18 | −11 | 5.7 |

| Andean Slopes | Variable | 800–3200 | 3500–700 | 12 | 3 | 7.6 |

| Coastal/Lowland Northern, Central, and Southern |

Variable | Sea level to Mountain range |

40 > 2000 | 23 21 17 |

−8 7 6 |

4.5 14 11 |

Quinoa ecoregions were inferred from information provided by passport data (germplasma.iniaf.gob.bo-GRIN global, accessed 15 April, 2020) and the characterization of Bolivian and Coastal ecoregions [88][90][91][112,120,121]. Disease traits data (mean values of severity and sporulation) from the South American diversity panel [40][52] were analyzed with the Tuckey test for their relationship with the seed-ecoregion collection site. For this analysis, we used Inti-Yupana for R [92][122], and the results pointed at significant differences for the variables. The graph represents data from means of sporulation only because data from means of severity was very similar (Figure 12).

Even though the sample size from the central highlands was overrepresented and the Coastal sample size was underrepresented, significant differences (p= 0.05) for severity and sporulation were detected. This ecoregion is suitable for pathogen infections and disease pressure. Moreover, principal component analysis of genome-wide association studies (GWASs) demonstrated that Puno is genetically close to Chilean coastal lines and separated from highlander genotypes [40][52]. The central highlands showed the largest quantity of susceptible genotypes, likely because they were also the most numerous.

In conclusion, the genetic improvement of quinoa for downy mildew tolerance is possible because resistance is present in multiple genotypes, but a virulent pathotype might overcome it. Other options to consider are discovering, transforming, and deploying resistant alleles existent in wild species such asC. albums[40][93][94][52,123,124]. Because tolerant varieties seem to delay and reduce the disease progression, inducers of resistance [95][96][125,126] could be a feasible option [81][108].

3. Ascomycete Fungi

3.1. Fungi Identified by Molecular and Morphological Approaches

3.1.1. Ascochyta Leaf Spot and Black Stem (Ascochyta hyalospora and A. chenopodii)

At least two Ascochyta species infect quinoa, causing quinoa leaf spot (described below) and black stem (described in next section). It was first found as a seed-borne pathogen ofC. quinoafrom the Bolivian central highlands, for which a blotter test (seed incubation method on well-soaked filter papers [97][127]) revealed 8%−26% of infection. It was identified morphologically, followed by pathogenicity tests causing whitish leaf spots 5 dpi, followed by pycnidia at 10 dpi, and necrosis on leaves and stem ofC. quinoaandC. albumplants [98][128]. (2013) isolated a fungal pathogen from quinoa fields in Pennsylvania, USA, and through DNA sequencing of the ITS1-2 region matched it

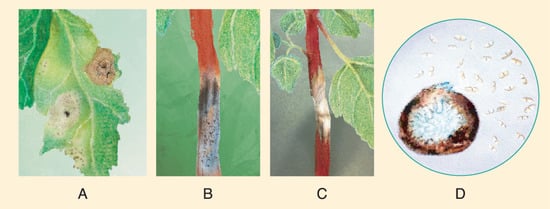

Ascochyta hyalospora pycnidia are globose to subglobose, usually 17.5 to 25 μm in diameter [98][128], and contain sub-hyaline to light-brown-colored conidia. Boerema (1977) noted that the conidia formed on leaf spots after artificial inoculation were longer (35 μm) and often had two or three septa (Figure 13E,F). Lesions on the leaves are of irregular shape, and are bronze to reddish-brown with darker edges. Thereafter, numerous black pycnidia, distributed randomly in each lesion, can be seen [99][129].

The stems show necrosis, and the pycnidia are visible to the naked eye (Figure 13A−D). [98][100][128,130]. Ascochyta leaf spots have been considered of minor importance in the Andean region [101][61][102][103][3,4,6,131]. In 2014, large-scale cultivation (12,000 ha) of quinoa started in China [104][132], where the production was affected. Experiments in Bolivia showed that the germination rates of seeds from infected plants were reduced by 6% to 10%.

Figure 13. Leaves showing symptoms of infection caused by A. hyalospora (A) on the adaxial side of the leaf and (B) on the abaxial side. (C) Stems showing pycnidia and brown stalk. (D) Stem showing pycnidia. (E) A. hyalospora conidia (Photos: Testen, 2020) [54][77]. (F) A. hyalospora: (a) pycnidium (×200); (b) conidiogenous cells of pycnidium (×1000); (c) conidia from pycnidium (×400); (d) bi and tri-septate conidia from pycnidium on an inoculated stem of C. quinoa (×400); (e) conidia from pycnidium on leafspot of inoculated leaf of C.quinoa (×400). Source: photos (A−E) provided by A.L. Testen. F. Adapted from [98][128].

3.1.2. Quinoa Black Stem (Ascochyta caulina)

Molecular and phylogenetic analysis of representative isolates from quinoa black-stem revealed that its causal agent is Ascochyta caulina (van der Aa and van Kesteren 1979). Gruyter et al. 2009), previously known asPleospora calvescens. of P. calvescens has changed recently, based on multigene analyses. These species share the same large phylogenetic branch with N. calvescens [105][106][107][108][109][133,134,135,136,137]. Ascohyta caulina in its asexual form belongs to the family Didymellaceae and has often been confused withA. hyalospora [109][137].

Compared to A. hyalospora leaf spots, black stem lesions were more likely to develop under cooler conditions [110][140]. Pathogenicity tests on detached stems of C. quinoa showed typical symptoms 10 dpi and were densely covered with pycnidia. At 15 dpi, typical symptoms appeared on the stems of plants inoculated in outdoor conditions. Detached inoculated leaves of C. quinoa developed visible symptoms 8 dpi and were grayish white.

Quinoa black stem primarily infects the stem; lesions are recorded at the flowering stage up to maturity. Symptoms first appear at the lower and middle parts of the stalk, subsequently moving upwards. They are diamond-shaped, pale or tan, and present slight depressions, as the plants are prone to drying and consequent shrinkage. The diameter of the lesion averages 7.9 cm.

The stem lesions turn necrotic in later stages and are accompanied by abundant small round protrusions of black pycnidia (Figure 14B,C). In severe cases, lesions wrap around the stem, causing lodging, foliar chlorosis, leaf abscission, and the development of “empty” and sterile grains on the panicle [109][137].

Figure 14. Typical symptoms of quinoa black stem in the fields of China. (A) Symptoms induced by inoculation of A. caulina on C. quinoa (left of midrib) and on C. album (right of midrib). (B) 10 dpi diamond shaped lesion on quinoa stem with presence of pycnidia. (C) Necrotic quinoa stem prior to lodging; (D) morphological characteristics of conidia and pycnidia of A. caulina. Source: illustrations based on pictures from Yin et al. [111][114].

Quinoa black stem is considered a newly emerging disease in Chinese regions (Jingle County, Shanxi province), where the disease was severe. The incidence was around 80% and the yield was reduced by 45% [109][110][137,140]. The fungicides mancozeb and azoxystrobin are shown to have a strong inhibitory effect on conidia germination, whereas tebuconazole and difenoconazole were most effective towards mycelial growth in tests performed in vitro [109][137].

Sixteen European countries concentrated integrative approaches for the biological control of the weed C. album from 1994 to 1999. The European Research Programme (COST-816) concerted the use of a combination of A. caulina with ascaulitoxin for this purpose [112][113][141,142]. Experiments using A. caulina as a microbial herbicide were up to 70% successful in reducing field conditions, as it was able to kill its host in one week [114][115][116][117][143,144,145,146].

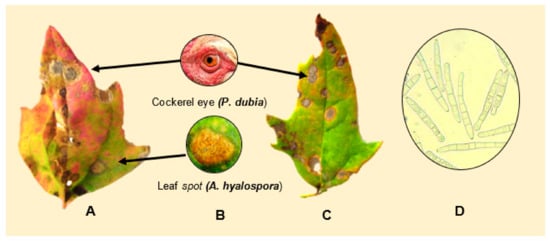

3.1.3. Cockerel Eye/Quinoa Cercorporoid Leaf Spot

Quinoa leaf spot was first reported in Ecuador (2009) and given the Spanish common name “ojo de gallo”, or cockerel eye, because of the symptoms exhibiting a dark center and round shape. It was then associated with Cercosporaspp. The genus Cercosporawas established by Fresenius (1863) and belongs to the family Mycosphaerellaceae, class Ascomycota. A comprehensive list of cercorporoids assembled in Poland included a species under the name Cercospora chenopodii Fresenus, 1863, found on C. album [118][148].

Testen et al, (2013) amplified the ITS1-2 region of strains isolated from quinoa field plots located in Pennsylvania, USA, and identified them as Passalora dubia (Riess) Conidia were septate, hyaline, and measured 25−98 5−10 μm wide—with an average of six cells per conidium (Figure 15D). Disease symptoms of leaves were round to oval with a diameter of less than 1 cm, and were brown to gray-black with darker brown or reddish borders (Figure 15A−C).

Figure 15. (A,C) depict symptoms of P. dubia on leaf tissue. (B) Comparison of “cockerel eye” and leaf spot symptoms. (D) Conidia of P. dubia. Source: pictures (A–C) provided by Testen and (D) Testen [54][77].

A pathogen identified as P. dubia has been tested as a microbial herbicide for the biocontrol of C. album in Europe. It was shown to reduce C. album’s dry weight by 20% [114][143].

Cercospora leaf spot, infecting quinoa in Shanxi, China, was classified asCercosporacf.chenopodiibased on multi-loci sequencing and phylogenetic analysis using LSU rpb2 and ITS as target genes. The qualifier “cf” indicates a provisional identification [119][150], even though most diagnostic characteristics correspond to C. chenopodii. Spore suspensions made in glycerin causes disease symptoms 5 dpi, spreads quickly, and produces large yellow lesions, which causes defoliation 10 dpi. Based on multigene phylogeny (LSU, rpb2, ITS, cmdA, and other genes), various Passalora species have been proposed to be re-classified as Cercospora Fresen.

3.1.4. Cercospora Leaf Spot Caused by Cercospora cf. chenopodii

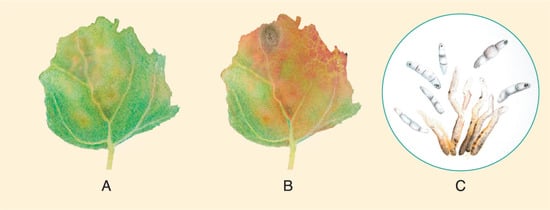

3.1.5. Quinoa Anthracnose Caused by Colletotrichum nigrum and C. truncatum

Stem lesions have been observed on quinoa plants growing in Ames, Iowa (USA). Symptoms are recognized as oval to linear, slightly narrow at the ends, light in color, silvery-white to dark gray, and are slightly sunken in lesions. They contain setose acervuli. Two isolates (CQ1, CQ2) were cultured in V8 media for the subsequent examination for their morphological characteristics and DNA barcoding [123][154].

They produced abundant sclerotia and conidia. The size of 50 conidia averaged 21 × 4.3 µm. They produced abundant sclerotia, acervuli, and conidia. Both isolates have been identified by multigene sequencing, and the multiple sequence alignment of vouchered CBS isolates generated a maximum likelihood phylogenetic tree.

For the completion of Koch postulates, 40-day-old quinoa plants (PI 634920) were inoculated on stems and leaves. After an extra week under humid conditions, the plants inoculated with C. nigrum produced acervuli (asexual stage) and sclerotia, whereas C. truncatum produced only acervuli. The morphological characteristics of grown mycelia matched those of the initial inoculum used on the plants. This disease may cause lodging and emerge in new quinoa production areas, resulting in yield losses [123][154].

3.2. Fungi Identified by Morphological Approaches

3.2.1. Brown Stalk Rot

Brown stalk rot was observed in C. quinoa growing in rotation with potatoes in the highlands of Puno, Peru, in 1974 and 1975. Its purpose was to demonstrate the presence of substance “E” (a colorless metabolite from exigua) in malt extract agar cultures of the fungus to distinguish it fromPhoma exiguavar.exigua [124][155]. The test gave a positive result for P. exigua var. foveata, and comparative morphological characteristics with the causal agent of potato gangrene were carried out [125][156]. As both were similar and pathogenicity tests on potatoes were positive, the quinoa brown stalk rot’s causal agent was identified as Phoma exigua var. foveata (Foister) Boerema.

Symptoms were described as follows: small lesions on the higher third of the stem progress until reaching the upper part. At this stage, pycnidia are visible, the foliage wilts, the panicle does not form grain, and the brown stalk is prone to break (Figure 17A). The pycnidia are globose and dark brown; their size ranges between 101−116 µm in diameter. The ostiole is 30 µm in diameter, and the pycnidiospores are hyaline, ellipsoidal, unicellular, and biguttulated (small drop-shaped).

Figure 17. (A) Brown stalk rot. (B) Diamond-shaped symptoms bearing pycnidia. Source: illustrations adapted from Alandia et al. [61][4].

Their average size ranged between 6 × 2.2 µm in artificial media and 6.8 × 2.3 µm when coming from infected stems. Cross-inoculations, aided (and not aided) with mechanical wounds, were performed on potato plants and tubers, tomato plants, beetroot, sugar beets, and quinoa. Quinoa plants showed symptoms 3 dpi, potatoes and tomato plants showed foliar blight, potato tubers got black rot, whereas beetroot and sugar beets showed no symptoms. Overall, mechanical wounds increased the rate of infection, but pycnidia were rarely observed.

Phoma exigua var. foveata because it is as pathogenic to potatoes as the virulent European isolates. On older leaves of both Chenopodium spp. , concentric leaf spots of 0.5−1.0 cm in diameter were visible. The European strain caused similar spots, but one week later [126][158].

3.2.2. Quinoa Diamond Black Stem/“Mancha Ojival del Allo”

Diamond black stem was observed The disease is primarily present in the stem, with diamond-shaped lesions (2−3 cm), whitish to gray in the center, with brown edges and a vitreous halo. They bear pycnidia. At a later stage, the lesions join around the stem, causing it to collapse [105][133]

Stem rot affecting The mycelium was cultured, and pathogenicity tests were carried out on three-month-old plants of quinoa, amaranth, potato, frejol, sunflower, andLupinus mutabilis. All plants were infected, and quinoa was the most susceptible. Inoculation with ascospores was followed by mycelial growth after 17 days.

3.2.3. Sclerotium in Quinoa

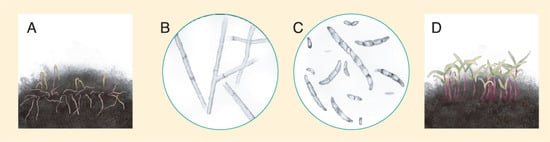

3.2.4. Damping-Off

-

Sensitivity of Pythium zingiberum and P. butleri oospores:Soil inoculation of oospores of P. zingiberum and P. butleri on soil caused damping-off of susceptible C. quinoa seedlings after ten days of incubation at 30 °C [160].

-

Seedling damping-off caused by Fusarium avenacearum and Pytium aphanidermatum:The fungi were isolated from infected stems of quinoa seedlings grown in a greenhouse. Microbes were morphologically described and the cultured fungi were inoculated on C. quinoa cv. Cochabamba. Pathogenicity tests confirmed that P. aphanidermatum and F. avenaceum were the causal agents of the damping-off of quinoa seedlings under greenhouse conditions. The seedling infection was significantly higher up to the first pair of leaves, showing that quinoa is most susceptible to the pathogens before emergence. However, the sum of post-emergence damping-off was significantly lower than that observed in sugar beets and higher than that observed in cabbage plants, except for F. avenacearum, which also produced marked susceptibility at the first true leaves stage. In addition to the two pathogens, Ascochyta caulina, Fusarium spp., and Alternaria spp were also isolated from infected tissue but could not infect quinoa seedlings during pathogenicity tests [139].

-

Pathogenicity tests on seedlings infected by Rhizoctonia solani and Fusarium spp.Rhizoctonia solani was isolated from the field in Peru. Pathogenicity tests performed in a greenhouse showed that R. solani prevented seed germination. It also created sunken lesions on the stems of old plants at ground level. Fusarium spp. reproduced wilting in old plants [4,161]. Quinoa seedling damping-off (Figure 18A) was observed during field experiments conducted at the experimental station of Nihon (Japan). It occurred from emergence until the four-leaf stage and increased under high soil moisture conditions. Rhizoctonia spp. (Figure 18B) and Fusarium spp. (Figure 18C) were identified morphologically from the symptomatic lesions [162].

Figure 18. (A) Quinoa seedlings affected by damping-off. (B) Rhizoctonia spp hyphae. (C) Fusarium spp. spores. (D) Healthy quinoa seedlings growing under low soil moisture conditions. Source: illustration adapted from Isobe et al. (2019) [124][155].

-

Pathogenicity tests on seedlings caused by Sclerotium rolfsii SaccSclerotium rolfsii was isolated from diseased seedlings of C. quinoa in a field of Southern California. The susceptibility of C. quinoa to S. rolfsii was demonstrated in vitro and under greenhouse conditions [163].

5. Bacteria

5.1. Bacterial Leaf Spot Caused by Pseudomonas spp.

Bacterial leaf symptoms are small irregular spots both in leaves and stems. In leaves, they turn dark brown with concentric rings and a wet halo; in stems, they become necrotic, causing a deep lesion and wilting [133].5.2. Bacterial Leaf Spot Caused by Pseudomonas syringae

Bacteria were isolated from symptomatic leaves and inoculates on surface sterilized leaves of quinoa cv. Piartal. Between three to fice dpi, leaf spots were visible (Figure 19). The bacteria colonies were identified at the species level via morphology and molecula tools using a Bruker Daltonik MALDI Biotyper system (Germany). The coucher for the identified bacteria was uploades to the NCBI database as txid317 [167]. Figure 19. Symptoms of bacterial leaf spot on quinoa. Source: illustration adapted from Fonseca-Guerra et al. [167].

Figure 19. Symptoms of bacterial leaf spot on quinoa. Source: illustration adapted from Fonseca-Guerra et al. [167]. -

6. Viruses

Pathogenicity assays for the identification of viruses under greenhouse conditions require indicator plants. These plants show distinctive and consistent reactions to virus infections. Many plant viruses can be transmitted to indicator plants via mechanical infection or insects. Nicotiana (tobacco) and Chenopodium are hosts for a great number of viruses [168]. Therefore, C. quinoa could be infected with the viruses that infect host plants that grow next to it.-

Chenopodium mosaic virus: Seedlings of C. quinoa were found to contain a highly infectious, seed-borne virus that may remain latent. The virus was restricted to the Chenopodiaceae and was similar to the soybean mosaic virus in morphology and physio-chemical properties [169].

-

Amaranthus leaf mottle virus (ALMV): Successful infections were achieved on C. quinoa, which exhibited chlorotic local lesions and severe systemic mosaic, leaf deformation, wilting, stunning, and finally collapse of the plants. Transmission via Aphis gossypii was confirmed 2 to 3 weeks after the 1-day inoculation access period [170].

-

Arracacha virus A: AVA is common in arracacha (Arracacia xanthorrhiza) in the region of the Peruvian Andes. AVA was not transmitted by Myzus persicae, but was transmitted by the inoculation of sap and is best propagated in C. quinoa and Nicotiana clevelandii [171,172,173].

-

Ullucus virus C: UVC is a comovirus prevalent in Ullucus tuberosus grown at high altitudes in the Bolivian and Peruvian Andes. It was transmitted mechanically to C. amaranticolor and C. quinoa. It caused a systemic infection. UVC was not transmitted by either aphid species (Aphis gossypii or Myzus persicae) or through seeds of C. quinoa. However, it was transmitted through leaf contact between infected and healthy plants, causing chlorosis [173].

-

Potato virus S (PVS): Chenopodium quinoa plants displayed symptoms of PVS infection 14 days after artificial inoculation with PVS [174,175].

-

Cucumber mosaic virus (CMV): Partially purified extracts from leaves of Phytolacca americana caused marked inhibition of CMV infection on C. quinoa [177].

-

Passiflora latent virus (PLV): Chenopodium quinoa plants presenting systemic symptoms after inoculation with PLV showed high concentrations of virus particles in their cytoplasm, mitochondria, and chloroplasts [179]

-

Plantago asiatica mosaic virus (PIAMV): Mechanical inoculation with infected sap of Lilium leaves on C. quinoa yielded chlorotic or necrotic local lesions [180].

-

5. Bacteria

5.1. Bacterial Leaf Spot Caused by Pseudomonas spp.

5.2. Bacterial Leaf Spot Caused by Pseudomonas syringae

Figure 19. Symptoms of bacterial leaf spot on quinoa. Source: illustration adapted from Fonseca-Guerra et al. [133].

Figure 19. Symptoms of bacterial leaf spot on quinoa. Source: illustration adapted from Fonseca-Guerra et al. [133].

6. Viruses

74. Chemical Control for Oomycetes and Fungi

The control of oomycete and fungal diseases continues to rely mainly upon chemical measures for conventional agriculture. These facts will continuously affect sensitivity to fungicides, requiring the repeated adaptation of control strategies [76][105]. The most recent fungicides of this type are phenyl-pyrroles (P.P. fungicides) and dimethylation inhibitors (DMIs). They are considered the most effective chemicals registered to control diseases caused by Ascomycetes [149][150][151][164,165,166], depicted in blue on Table 7. The table aims to provide a general reference. The choice of fungicide is highly dependent on the availability and conditions of the particular fields to be treated.

| Mode of Trans-location | Fungicide Group and Key Active Ingredients | Resistance Risk a | Foliar | Seed | Soil | Type of Activity | Translocation in Plants | Biochemical Mode of Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully Systemic |

Phenylamides: Metalaxyl, mefenoxam, oxadixyl, benalaxyl, kiralaxyl, ofurace |

High | √ | √ | Preventive, curative, eradicative | Apoplastic, symplastic, translaminar | Inhibition of rRNA synthesis | |

| Partially Systemic |

b Quinone outside inhibitors: Azoxystrobin, fenamidone, famox, adone, trifloxystrobin: kresoxin-methyl, Pyraclostrobin |

√ | √ | Preventive | translaminar apoplastic | Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration at enzyme complex III | ||

| Non-Systemic | b Multisites: For example, mancozeb; chlorothalonil, copper, cu-oxychloride, cu-hydroxide; folpet; thiram, chlorothalonil |

Low | √ | Preventive | Multi-site inhibition | |||

| Non-Systemic | Carboxylic acid amides: Dimethomorph, flumorph; iprovalicarb, benthiavalicarb; mandipropamid |

Moderate | √ | Preventive | Translaminar | Cell wall synthesis, Ces3A cellulose synthase inhibition | ||

| Fully Systemic |

Cyanoacetamide, oximes (cymoxanil) | Moderate | √ | √ | Preventive, curative | Apoplastic, symplastic, translaminar | Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration at the enzyme complex III | |

| Non-Systemic | Dinitroanilines (fluazinam) | Moderate | Preventive | Inhibition of ATP production | ||||

| Fully Systemic |

Phosphonates (fosetyl-Al) | Moderate | √ | Preventive, curative | Apoplastic, symplastic, | Inhibition of spore germination, retardation of mycelia | ||

| Partially Systemic |

Quinone inside respiration inhibitors: Cyazofamid, amisulbrom |

Medium to hight | √ | √ | Preventive, curative, eradicative/ | Translaminar | ||

| Fully Systemic |

Benzamides (fluopicolide) | Mod. | √ | √ | Preventive, curative | Apoplastic, symplastic, translaminar | Delocalization of spectrin-like proteins | |

| Benzamides, carboxamides Ethaboxam, zoxamide |

Low | |||||||

| Systemic | Hymexaxol (heteroaromatics) | √ | √ | Fungal RNA and DNA syntheses | ||||

| Contact | b Thiadiazoles (Etridiazole) | √ | Preventive, curative | Lipid structure of Mitochondria | ||||

| Resistance inducer | Acibenzolar-S-methyl. | √ | ||||||

| b Demethylation inhibitor fungicides (DMIs): Imidazoles, triazolinthiones, triazoles prothioconazole, prochloraz, terbuconazole, difenoconazole |

√ | √ | Preventive, curative | Sterole biosynthesis in membranes | ||||

| b PP fungicides (Phenylpyrroles) phenylpyrroles Fludioxonil |

√ | √ | Preventive, curative | Signal transduction | ||||

| Fully Systemic |

Carbamates: Propamocarb, prothiocarb | Preventive, eradicative | Apoplastic | Multi-site inhibition Affecting the membrane |

87. Conclusions and Future Directions

Morphological identification paired with molecular tools for accurate descriptions of causal agents, published in scientific journals, as well as the sharing of knowledge within quinoa networks and conferences.

The performance of inclusive pathogenicity tests and Koch’s postulates to clarify the type of interaction observed (e.g., pathogenic, endophytic/symbiotic, or saprophytic.).

Standardized protocols for disease propagation and assessment methods for severity after infection.

The development of strategies for seed sanitation.

There exist several research centers located in areas where quinoa is traditionally grown, and recently a pilot global collaborative network on quinoa (GCN-Quinoa) (www.gcn-quinoa.org, accessed on 10 June 2021) has been established [158]. These networks primarily share knowledge on cultivation and plant breeding. Knowledge sharing in relation to quinoa diseases should also be considered.

More research on methodologies for the rapid, high throughput screening of quinoa seeds and plants for the presence of economically important pathogens of quinoa is needed. This would be useful for detecting causal agents early in disease development and ensuring certified pathogen-free quinoa seeds. Moreover, phone apps with deep learning models for diagnosing various plant diseases and pest attacks are becoming interesting tools, which may be useful in the future.

- Morphological identification paired with molecular tools for accurate descriptions of causal agents, published in scientific journals, as well as the sharing of knowledge within quinoa networks and conferences.

- The performance of inclusive pathogenicity tests and Koch’s postulates to clarify the type of interaction observed (e.g., pathogenic, endophytic/symbiotic, or saprophytic.).

- Standardized protocols for disease propagation and assessment methods for severity after infection.

- The development of strategies for seed sanitation.

- There exist several research centers located in areas where quinoa is traditionally grown, and recently a pilot global collaborative network on quinoa (GCN-Quinoa) (www.gcn-quinoa.org, accessed on 10 June 2021) has been established [189]. These networks primarily share knowledge on cultivation and plant breeding. Knowledge sharing in relation to quinoa diseases should also be considered.

- More research on methodologies for the rapid, high throughput screening of quinoa seeds and plants for the presence of economically important pathogens of quinoa is needed. This would be useful for detecting causal agents early in disease development and ensuring certified pathogen-free quinoa seeds. Moreover, phone apps with deep learning models for diagnosing various plant diseases and pest attacks are becoming interesting tools, which may be useful in the future.