Integrated optical phased arrays (OPAs) can be used for beam shaping and steering with a small footprint, lightweight, high mechanical stability, low price, and high-yield, benefiting from the mature CMOS-compatible fabrication.

- integrated

- optical phased arrays

- beam shaping

- beam steering

1. Introduction

In recent years, optical p

In recent years, optical phased arrays (OPAs) have attracted a great deal of attention. At optical wavelengths, small diffraction angles for a given aperture size can be achieved, compared with microwave radar systems. Featured by precise and agile free-space beam forming and steering [1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12], OPA techniques are highly desirable. However, current commercially available OPA components are mainly based on mechanical control, such as motor-driven rotating collimation stages/mirrors. Mechanical beam steering provides high efficiency and a relatively large scanning angle, through mechanically moving parts such as a gimbal, which can be susceptible to mechanical wear and tear, less stable, and limited in speed [13][14] due to the masses involved. The bulky mechanical steering approach is less preferred as it typically degrades in performance due to acceleration, temperature, vibration, and inertial forces. Additionally, mechanical steering often consumes significant energy. Furthermore, they require a complex assembly and calibration process, causing a greatly high unit cost. More importantly, these mechanical approaches are only capable of steering a single light beam. Arbitrary pointing and rapid steering as needed for advanced communication and sensing applications then become difficult or even incapable [14][15][16][17][18][19].

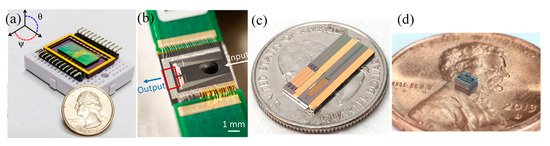

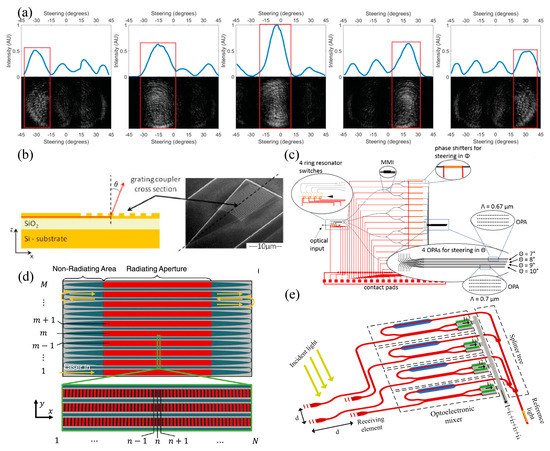

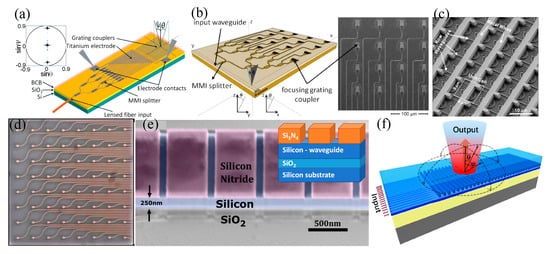

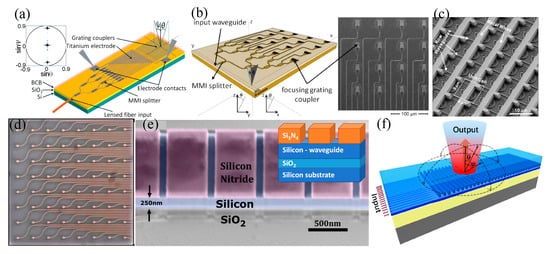

As one of the promising solutions for the next-generation dynamic beam steering, integrated OPAs simultaneously possess the advantages of being stable, rapid, and precise without relying on any mechanical motion, making them robust and insensitive to external constraints such as accelerations. Some of the integrated OPAs are presented in Figure 1. A wire-bonded device on a chip carrier plugged into a breadboard is presented in Figure 1a. Figure 1b shows a one-dimensional 64-channel chip-scale blue light phased array. A kind of III-V/Si phase-shifter-based OPA is shown in Figure 1c. Figure 1d is the photo of a fabricated OPA chip on a penny. Using an integrated approach, the OPAs can be made very small.

Figure 1. Integrated OPAs. (a) The wire-bonded device on the chip carrier plugged into the breadboard. Reprinted with permission from [20] © The Optical Society. (b) Blue light OPA. Reprinted with permission from [21] © The Optical Society. (c) A set of three 32-channel and one 240-channel OPAs on a coin. Reprinted with permission from the author of [22] published on Arxiv, 2018. (d) A photo of an OPA on a penny. Reprinted with permission from [23] © The Optical Society.

2. Principles

2.1. Fraunhofer Diffraction Model

Thased arrays (OPAs) have attracted a great deal of attention. At optical wavelengths, small Fraunhofer diffraction angles for a given aperture size can be achieved, compared with microwave radar systems.theory Featured[24] by precise and agile free-space beam forming and steering [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12], OPA techniqan be ues are highly desirable. However, current commercially available OPA components are mainly based on mechanical control, such as motor-driven rotating collimation stages/mirrors. Mechanical beam steering provides high efficiency and a relatively large scanning angle, through mechanically moving parts such as a gimbal, which can be susceptible to mechanical wear and tear, less stable, and limited in speed [13,14] due ed to describe the far-field into the masses involved. The bulky mechanical steering approach is less preferred as it typically degrades in performance due to acceleration, temperature, vibration, and inertial forces. Additionally, mechanical steering often consumes significant energy. Furthermore, they require a complex assembly and calibration process, causing a greatly high unit cost. More importantly, these mechanical approaches are only capable of steering a single light beam. Arbitrary pointing anrference of OPAs, in which scalar field rapide steering as needed for advanced communication and sensing the ax0y0-pplications then become difficult or even incapable [14,15,16,17,18,19].

As one of ane diffracthe promising solutions for to the nextx1y1-generation dynamic beam steering, integrated OPAs simultaneously possess the advantages of being stable, rapid, and precise without relying on any mechanical motion, making them robust and insensitive to external constraints such as accelerations. Some of the integrated OPAs are presented in Figure 1. A wire-bonded device on a chip carrier plugged into a breadboard ilane at a large dis presented in Figure 1a. Figure 1b shows a one-dimensional 64-channele chip-scalez0 blue[13], light phased array. A kind of III-V/Si phase-shifter-based OPA is shown in Figure 1c. Figure 1d is the photo of a fabricated OPA chip on a penny. Using an integrated approach, the OPAs can be made very smaoll.

Figure 1. Integrated OPAs. (a) The owire-bonded device on the chip carrier plugged into the breadboard. Reprinted with permission from [40] © The Optical Society. (b) Blg the rue light OPA. Reprinted with permission from [41] © The Opticae bel Society. (c) A set of three 32-channel and one 240-channel OPAs on a coin. Reprinted with permission from the author of [42] published on Arxiv, 2018. (d) A photo of an OPA on a penny. Reprinted with permission from [43] © The Optical Society.:

2. Principles

2.1. Fraunhofer Diffraction Model

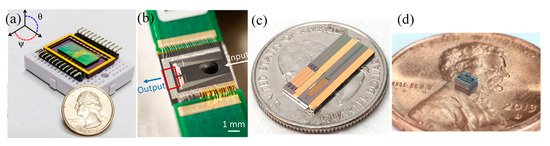

Figure 2. (a) Scwhematic of an OPA basred onk WGAis. Reprinted with permission from [13], © G the frent University. (b) An OPA b-spasced on EF structures. Reproduced from [18] published by De G wave vectoruyter, 2016.

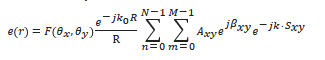

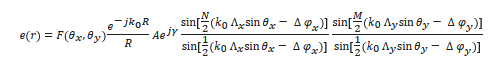

In pForinciple, the far-fieldN radiation× pattern ofM OPAs is calculated by the far field of individualpresented in Figure 2antenna, multiplied by the array factor [10,58,59]. The the far far-field pattern can be desirably modulated based on this theory.

2.2. Multi-Slit Diffraction Model

Figure 3. (a) Half-waveleat a certaingth element spacingpoint OPAr with integrated TO heaters for beam steering from left to right. Reproduced from [61] with the s the far-field permission of AIP Publishing. (b) Schematic view of the cross section of a WGA. Reprinted with permission from [8] © The Opern of one elementical, Society.i.e., F (cθx, θy), Schematic image of the proposed 2D beam steering device at a fixed wavelength. Reprinted with permission from [62] © The Omultiplied by the sum of all the ptical Society. (d) Schematic of a serpentine OPA. Reprinted with permission from [63] © The Opticse fal Society. (e) A 2 × 2 OPA toreceiver. Reprinted with permission from [43] © The Optical Society.[13]:

2.3. Beam Steering Based on WGAs

Nearly all twhe proposedre 2DR OPAs= till|r|, nowAxy depend on WGAis. Not all the 2D OPAs’ far- the field patterns are completelyamplitude, formed by phaseβxy differences. There are some other steering approaches.

3. Building Blocks

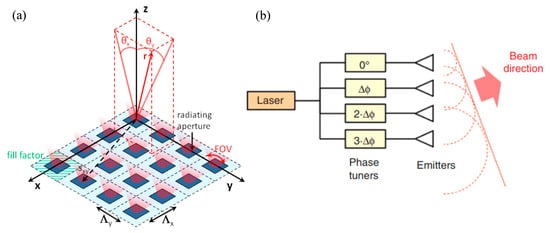

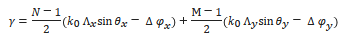

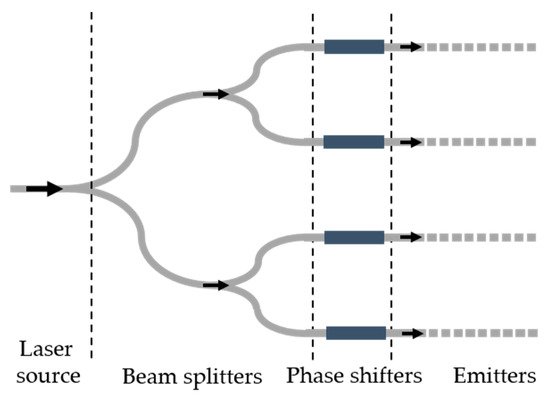

Integrated photonics paves the way for low-cost large-scale OPA chips. As presented in Figure 4, typically, there are four necessary parts in an OPA: laser source, beam splitters, phase shifters, and emitters [12], for efficient light generation, manipulation, and chip-to-free-space transmission. We will discuss each part in detail in this section. Then a brief overview about overlayers and buried oxide (BOX) layers is given. The optimized thicknesses of the overlayers and BOX layers enhance the upward radiation of WGAs.

Figure 4. A typical integrated OPA structure.

4. Configurations

In terms of emitter types, OPAs can be sorted into EF OPAs, WGA-based OPAs, and OPAs based on other emitter structures.

4.1. EF OPAs

Typicals the rely, EF OPAs can only be tuned by the tive phase difference between adjacentat each elements., Ask0 preisented in Figure 7a, the first experimentally demonstrated aperiodic OPA was implemented on SOI [9]. The 12ee-channel unequal spaced OPA with a silica (SiO2) o waverlay and individual TO phase shifters enabled an FOV of 31.9° at 1.55 μm [9].

Figure 7. EF OPA structures. (a) A SOI-basevector, and EFSxy OPA. Reproduced from [9] withs the permissosition of AIP Publishing. (b) Ththe first demonstrated half-wavelength spacing OPA. Reproduced from [61] with thadiating eleme permissiont. ofθx AIP Publishiang.d (c)θy A dispersion-engineered half-wavelength EF OPA with low crosstalk. Reprinted with permission from the author ondicate the angle of [94]x- publisheand on Arxiv, 2018. (d) A SOIy-based EF OPA with a SiO2irection, cavity for envelope tailoring. Reprinted with permission from [59] © The Opticespectively. For uniform arral Society.s (e) A[13], 1D 64-channel blue OPA with sparse aperiodic spacing. Reprinted e far field is:

with permission from [41] © There Opticalγ Society. (f)s a Scphematic of a 16-channel polymer EF OPA. Reprinted with permission from [98] © Thase factor determined Optical Societby.

where Λx and Λy are the element spacing along the x- and y-axis, respectively. Δφx and Δφy are the phase differences.

Figure 2. (a) Schematic of an OPA based on WGAs. Reprinted with permission from [13], © Gent University. (b) An OPA based on EF structures. Reproduced from [18] published by De Gruyter, 2016.

In principle, the far-field radiation pattern of OPAs is calculated by the far field of individual antenna multiplied by the array factor [10][25][26]. The far-field pattern can be desirably modulated based on this theory.

4.2. WGA-Based OPAs

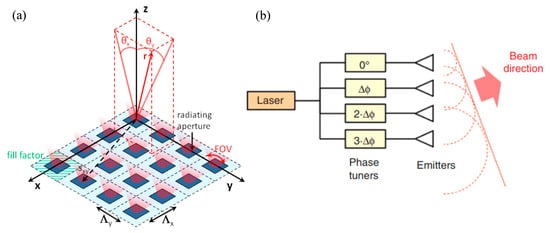

2.2. Multi-Slit Diffraction Model

The first OPA introduced in Si photonics was implemented based on WGA structures, as presens illustrated in Figure 8a.Figure 2b, Theuniform 1D 16-element WGA-based OPA was fabricated on the SOI platform. An FOV of 2.3° × 14.1° was demonstrated with both TO phase modulation and wavelength tuning [7]EF OPAs can be described by the multi-slit diffraction model. AThe 4 × 4 WGA-based OPA with an FOV of 1.5° was subsequently realized by the same group (Figure 8b). WEF OPA is regarded as a rectavelength tuning based on grating dispersion was exploited to decrease the number of phase controls [8]ular aperture array in the diffraction model. Then achieved FOV of 1.5° is relatively narrow due to the small fill factor of the OPA, which can be further improved by redesigning OPA with a proper fill factor. Athe far-field angular intensity distribution 8[13][26][27] × 8 WGA-based OPA with Si heaters presented s in Figure 8c enablthed an FOV of 6° × 6° and a beamwidth of 1.6° × 1.6°. Ligform of:

whtly dopered Siδx waveguides, which provided considerable resistances and low optical losses, and heavilys the element size of the dopN-ed Si leads were usedment OPA, asI0 heaters to drop most of the heating power on waveguides. Zigzagged Si lead structures were used to increase the heating lengthtands for the unitary peak intensity in the far field of a single element, and toθx provide thermal isolations between waveguidesndicates the angle of anx-d miretal contactsction. The measured TO efficiency was about 8.5 mW per π phase shift [58].

Figure 8. WGA-basidentical phase diffed OPAs. (a) Thre first OPA introduced in Sice of Δφx photonics. Reprinted with permission from [7] © Ts applied between adjacent channe Optical Society. (b) A 4 × 4ls placed at WGA-based OPA. Reprinted with permission from [8] pitch of Λx. © The Optical Society. (c) SEM ofF a fabricated OPA after dry etching away the dielectric SiO2. ROPAs are commonly used to achieprintved with permission from [87] © The Opt 1D beam formical Society. (d) Ang 8 × 8 OPA receiver. Reprinted with permission from [43] © Tand steering by phe Optical Society. (e) False-colored tshilted SEM of an aperiodic Si/Si3N4 grafting. Reprinted with permission frombetween waveguides. As shown in [109]Figure 3a, © Tthe Optical Society. (f) A hfirst fabrigh contrast WGA-basated OPA with high efficiency and low crosstalk. Reprinted with permission from [110] © The Oa half-wavelength element sptical Society.

5. Material Platforms

Icintegrated OPAs is used to demonstrated on photonics platforms enable low-cost chip-scale applications. In addition to conventional Si platforms, OPAs have been implemented on other photonic beam steering over a range of 64° by integrated platforms. The major platforms of integrated OPAs, which include Si photonics platforms, III/V platforms, and III–V/Si hybrid platforms.

7. Performances

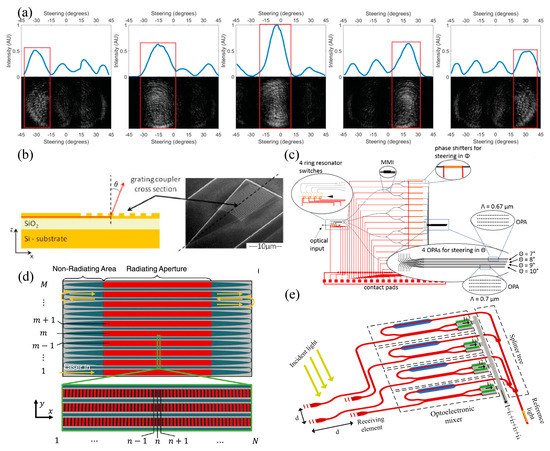

thermo-optic (TO) heaters. The main evaluation parameters of OPAs, which are FOVs, beamwidths and sidelobe suppression, modulation speeds, power consumption. It is important to note that one of critical factors determining FOVs, beamwidths and sidelobe suppression is the crosstalk and suppression among arrayed waveguide channels, and the efforts paid to reduce it should be reviewed first. For high-performance applications, large-scale OPAs are necessary. The scalability of OPAs will also be discussed. Finally, the calibration of OPAs to compensate for fabrication errors and mitigate crosstalkasured intensity of the horizontal cross sections and stitched-together captured images are presented at the top and the bottom will be shown[28].

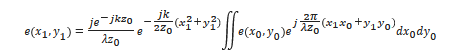

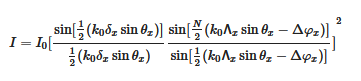

Figure 3. (a) Half-wavelength element spacing OPA with integrated TO heaters for beam steering from left to right. Reproduced from [28] with the permission of AIP Publishing. (b) Schematic view of the cross section of a WGA. Reprinted with permission from [8] © The Optical Society. (c) Schematic image of the proposed 2D beam steering device at a fixed wavelength. Reprinted with permission from [29] © The Optical Society. (d) Schematic of a serpentine OPA. Reprinted with permission from [30] © The Optical Society. (e) A 2 × 2 OPA receiver. Reprinted with permission from [23] © The Optical Society.

2.3. Beam Steering Based on WGAs

Nearly all the proposed 2D OPAs till now depend on WGAs. Not all the 2D OPAs’ far-field patterns are completely formed by phase differences. There are some other steering approaches.

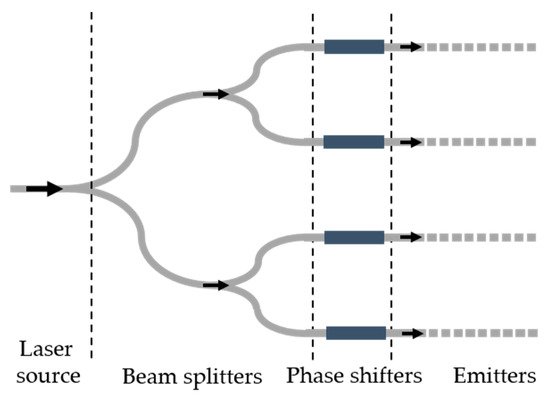

3. Building Blocks

Integrated photonics paves the way for low-cost large-scale OPA chips. As presented in Figure 4, typically, there are four necessary parts in an OPA: laser source, beam splitters, phase shifters, and emitters [12], for efficient light generation, manipulation, and chip-to-free-space transmission. We will discuss each part in detail in this section. Then a brief overview about overlayers and buried oxide (BOX) layers is given. The optimized thicknesses of the overlayers and BOX layers enhance the upward radiation of WGAs.

Figure 4. A typical integrated OPA structure.

4. Configurations

In terms of emitter types, OPAs can be sorted into EF OPAs, WGA-based OPAs, and OPAs based on other emitter structures.

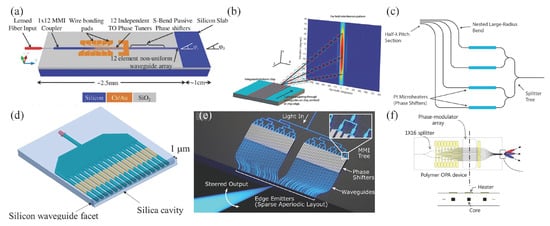

4.1. EF OPAs

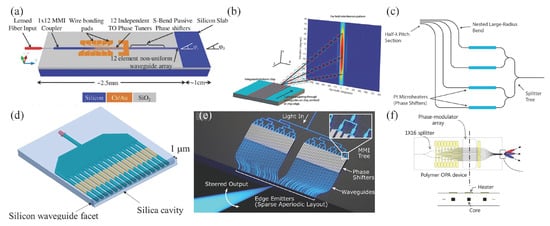

Typically, EF OPAs can only be tuned by the phase difference between adjacent elements. As presented in Figure 5a, the first experimentally demonstrated aperiodic OPA was implemented on SOI [9]. The 12-channel unequal spaced OPA with a silica (SiO2) overlay and individual TO phase shifters enabled an FOV of 31.9° at 1.55 μm [9].

Figure 5. EF OPA structures. (a) A SOI-based EF OPA. Reproduced from [9] with the permission of AIP Publishing. (b) The first demonstrated half-wavelength spacing OPA. Reproduced from [28] with the permission of AIP Publishing. (c) A dispersion-engineered half-wavelength EF OPA with low crosstalk. Reprinted with permission from the author of [31] published on Arxiv, 2018. (d) A SOI-based EF OPA with a SiO2 cavity for envelope tailoring. Reprinted with permission from [26] © The Optical Society. (e) A 1D 64-channel blue OPA with sparse aperiodic spacing. Reprinted with permission from [21] © The Optical Society. (f) Schematic of a 16-channel polymer EF OPA. Reprinted with permission from [32] © The Optical Society.

4.2. WGA-Based OPAs

The first OPA introduced in Si photonics was implemented based on WGA structures, as presented in Figure 6a. The 1D 16-element WGA-based OPA was fabricated on the SOI platform. An FOV of 2.3° × 14.1° was demonstrated with both TO phase modulation and wavelength tuning [7]. A 4 × 4 WGA-based OPA with an FOV of 1.5° was subsequently realized by the same group (Figure 6b). Wavelength tuning based on grating dispersion was exploited to decrease the number of phase controls [8]. The achieved FOV of 1.5° is relatively narrow due to the small fill factor of the OPA, which can be further improved by redesigning OPA with a proper fill factor. An 8 × 8 WGA-based OPA with Si heaters presented in Figure 6c enabled an FOV of 6° × 6° and a beamwidth of 1.6° × 1.6°. Lightly doped Si waveguides, which provided considerable resistances and low optical losses, and heavily doped Si leads were used as heaters to drop most of the heating power on waveguides. Zigzagged Si lead structures were used to increase the heating length and to provide thermal isolations between waveguides and metal contacts. The measured TO efficiency was about 8.5 mW per π phase shift [25].

Figure 6. WGA-based OPAs. (a) The first OPA introduced in Si photonics. Reprinted with permission from [7] © The Optical Society. (b) A 4 × 4 WGA-based OPA. Reprinted with permission from [8] © The Optical Society. (c) SEM of a fabricated OPA after dry etching away the dielectric SiO2. Reprinted with permission from [33] © The Optical Society. (d) An 8 × 8 OPA receiver. Reprinted with permission from [23] © The Optical Society. (e) False-colored tilted SEM of an aperiodic Si/Si3N4 grating. Reprinted with permission from [34] © The Optical Society. (f) A high contrast WGA-based OPA with high efficiency and low crosstalk. Reprinted with permission from [35] © The Optical Society.

5. Material Platforms

Integrated OPAs demonstrated on photonics platforms enable low-cost chip-scale applications. In addition to conventional Si platforms, OPAs have been implemented on other photonic integrated platforms. The major platforms of integrated OPAs, which include Si photonics platforms, III/V platforms, and III–V/Si hybrid platforms.

6. Performances

The main evaluation parameters of OPAs, which are FOVs, beamwidths and sidelobe suppression, modulation speeds, power consumption. It is important to note that one of critical factors determining FOVs, beamwidths and sidelobe suppression is the crosstalk and suppression among arrayed waveguide channels, and the efforts paid to reduce it should be reviewed first. For high-performance applications, large-scale OPAs are necessary. The scalability of OPAs will also be discussed. Finally, the calibration of OPAs to compensate for fabrication errors and mitigate crosstalk will be shown.

97. Outlook

More applications can be achieved based on integrated OPAs. Monolithically integrated OPAs take advantage of full integration and small chip sizes. EF OPAs can be used for 1D beam forming and steering. Wavelength-tuned 1D long-WGA-based OPAs with phase modulations decrease steering complexities in 2D steering. Problems of expensive precisely tunable laser sources [11,45] and limited performance [64,84] could be solved. Simplified high-performance on-chip tunable lasers are highly desirable. Large-scale sparse aperiodic 2D OPAs, which have wide FOVs and narrow beamwidths, are promising candidates for high-performance OPA-based applications. Design complexity of large-scale sparse aperiodic 2D OPAs need to be decreased for further applications. A two-chip integrated OPA with a sparse aperiodic aperture might be a promising solution [45].

More applications can be achieved based on integrated OPAs. Monolithically integrated OPAs take advantage of full integration and small chip sizes. EF OPAs can be used for 1D beam forming and steering. Wavelength-tuned 1D long-WGA-based OPAs with phase modulations decrease steering complexities in 2D steering. Problems of expensive precisely tunable laser sources [11][36] and limited performance [37][38] could be solved. Simplified high-performance on-chip tunable lasers are highly desirable. Large-scale sparse aperiodic 2D OPAs, which have wide FOVs and narrow beamwidths, are promising candidates for high-performance OPA-based applications. Design complexity of large-scale sparse aperiodic 2D OPAs need to be decreased for further applications. A two-chip integrated OPA with a sparse aperiodic aperture might be a promising solution [36].

For applications based on precise beam forming and steering, WGAs with normal direction radiation [64,113] as well as structures with plateau envelops [59,113,118] can be highly desirable Modulation speeds are greatly enhanced by EO phase shifters based on the carrier density changing function. Monolithically integrated LiNbO

For applications based on precise beam forming and steering, WGAs with normal direction radiation [37][39] as well as structures with plateau envelops [26][39][40] can be highly desirable Modulation speeds are greatly enhanced by EO phase shifters based on the carrier density changing function. Monolithically integrated LiNbO

3 EO phase shifters [105] and contact graphene heaters with high efficiencies and operation speeds, low power consumption [75] can be used for excellent EO modulations. To decrease optical losses of sharp waveguide bends, 45° angle placed antennas may be used to enable optical routing through two sides of the aperture [45]. Fabrication errors need to be carefully treated [142].

EO phase shifters [41] and contact graphene heaters with high efficiencies and operation speeds, low power consumption [42] can be used for excellent EO modulations. To decrease optical losses of sharp waveguide bends, 45° angle placed antennas may be used to enable optical routing through two sides of the aperture [36]. Fabrication errors need to be carefully treated [43].

References

- Wight, D.R.; Heaton, J.M.; Hughes, B.T.; Birbeck, J.C.H.; Hilton, K.P.; Taylor, D.J. Novel phased array optical scanning device implemented using GaAs/AlGaAs technology. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1991, 59, 899–901.

- Webb, G.W.; Vernon, W.; Sanchez, M.S.; Rose, S.C.; Angello, S. Optically controlled millimeter wave antenna. In Proceedings of the International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics, Melbourne, Australia, 17–19 November 1999; p. 275.

- Webb, G.W.; Vernon, W.; Sanchez, M.S.; Rose, S.C.; Angello, S. Novel photonically controlled antenna for MMW communications. In Proceedings of the International Topical Meeting on Microwave Photonics, Oxford, UK, 11–13 September 2000; p. 176.

- Igor, V.M.; Oleg, V.M. The brief elementary basics of antenna arrays. In Basic Principles of Fresnel Antenna Arrays, 1st ed.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2008; pp. 1–12.

- Xiao, F.; Hu, W.; Xu, A. Optical phased-array beam steering controlled by wavelength. Appl. Opt. 2005, 44, 5429–5433.

- Hosseini, A.; Kwong, D.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Crnogorac, F.; Fabian, R.; Pease, W.; Chen, R.T. Unequally spaced waveguide arrays for silicon nanomembrane-based efficient large angle optical beam steering. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2009, 15, 1439–1446.

- Acoleyen, K.V.; Bogaerts, W.; Jágerská, J.; Thomas, N.L.; Houdré, R.; Baets, R. Off-chip beam steering with a one-dimensional optical phased array on silicon-on-insulator. Opt. Lett. 2009, 34, 1477–1479.

- Acoleyen, K.V.; Rogier, H.; Baets, R. Two-dimensional optical phased array antenna on silicon-on-insulator. Opt. Express 2010, 18, 13655–13660.

- Kwong, D.; Hosseini, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, R.T. 1 × 12 Unequally spaced waveguide array for actively tuned optical phased array on a silicon nanomembrane. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 99, 051104–051106.

- Sun, J.; Timurdogan, E.; Yaacobi, A.; Hosseini, E.S.; Watts, M.R. Large-scale nanophotonic phased array. Nature 2013, 493, 195–199.

- Poulton, C.V.; Byrd, M.J.; Russo, P.; Timurdogan, E.; Khandaker, M.; Vermeulen, D.; Watts, M.R. Long-range LiDAR and free-space data communication with high-performance optical phased arrays. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2019, 25, 7700108.

- Hutchison, D.N.; Sun, J.; Doylend, J.K.; Kumar, R.; Heck, J.; Kim, W.; Phare, C.T.; Feshali, A.; Rong, H. High-resolution aliasing-free optical beam steering. Optica 2016, 3, 887–890.

- Acoleyen, K.V. Nanophotonic Beam Steering Elements Using Silicon Technology for Wireless Optical Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2012.

- Kim, T.; Bhargava, P.; Poulton, C.V.; Notaros, J.; Yaacobi, A.; Timurdogan, E.; Baiocco, C.; Fahrenkopf, N.; Kruger, S.; Ngai, T.; et al. A single-chip optical phased array in a wafer-scale silicon photonics/CMOS 3D-integration platform. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2019, 54, 3061–3074.

- Chang, Y.C.; Miller, S.A.; Phare, C.T.; Shin, M.C.; Zadka, M.; Roberts, S.P.; Stern, B.; Ji, X.; Mohanty, A.; Gordillo, O.A.J.; et al. Scalable low-power silicon photonic platform for all-solid-state beam steering. In Proceedings of the Micro- and Nanotechnology Sensors, Systems, and Applications XI, Baltimore, MD, USA, 13 May 2019; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2019; Volume 10982.

- Chung, S.W.; Abediasl, H.; Hashemi, H. A monolithically integrated large-scale optical phased array in silicon-on-insulator CMOS. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2018, 53, 275–296.

- Poulton, C.V.; Yaacobi, A.; Cole, D.B.; Byrd, M.J.; Raval, M.; Vermeulen, D.; Watts, M.R. Coherent solid-state LiDAR with silicon photonic optical phased arrays. Opt. Lett. 2017, 42, 4091–4094.

- Heck, M. Highly integrated optical phased arrays, photonic integrated circuits for optical beam shaping and beam steering. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 93–107.

- Luo, X. Engineering Optics 2.0, a Revolution in Optical Theories, Materials, Devices and Systems, 1st ed.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; p. 647.

- Kwong, D.; Hosseini, A.; Covey, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, X.; Subbaraman, H.; Chen, R.T. On-chip silicon optical phased array for two-dimensional beam steering. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 941–944.

- Shin, M.C.; Mohanty, A.; Watson, K.; Bhatt, G.R.; Phare, C.T.; Miller, S.A.; Zadka, M.; Lee, B.S.; Ji, X.; Datta, I.; et al. Chip-scale blue light phased array. Opt. Lett. 2020, 45, 1934–1937.

- Xie, W.; Komljenovic, T.; Huang, J.; Davenport, M.L.; Bowers, J.E. Dense III-V/Si phase-shifter based optical phased array. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1904.01104.

- Fatemi, R.; Abiri, B.; Khachaturian, A.; Hajimiri, A. High sensitivity active flat optics optical phased array receiver with a two-dimensional aperture. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 29983–29999.

- Goodman, J.W. Introduction to Fourier Optics, 2nd ed.; McGraw-Hill, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 74–75.

- Sun, J.; Timurdogan, E.; Yaacobi, A.; Su, Z.; Hosseini, E.S.; Cole, D.B.; Watts, M.R. Large-scale silicon photonic circuits for optical phased arrays. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2014, 20, 8201115.

- Xu, W.; Zhou, L.; Lu, L.; Chen, J. Aliasing-free optical phased array beam-steering with a plateau envelope. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 3354–3368.

- Wu, Z.; Jiang, W.; Xia, J.; Huang, Q. Optical phased array antenna with wide steering range using grating array superlattices. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Optical and Photonic Engineering, Shanghai, China, 24 July 2018; Yu, Y., Zuo, C., Qian, K., Eds.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2018; p. 108272U.

- Kossey, M.R.; Rizk, C.; Foster, A.C. End-fire silicon optical phased array with half-wavelength spacing. APL Photonics 2018, 3, 011301.

- Tyler, N.A.; Fowler, D.; Malhouitre, S.; Garcia, S.; Grosse, P.; Rabaud, W.; Szelag, B. SiN integrated optical phased arrays for two-dimensional beam steering at a single near-infrared wavelength. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 5851–5858.

- Dostart, N.; Zhang, B.; Khilo, A.; Brand, M.; Qubaisi, K.A.; Onural, D.; Feldkhun, D.; Wagner, K.H.; Popović, M.A. Serpentine optical phased arrays for scalable integrated photonic lidar beam steering. Optica 2020, 7, 726–733.

- Phare, C.T.; Shin, M.C.; Miller, S.A.; Stern, B.; Lipson, M. Silicon optical phased array with high-efficiency beam formation over 180 degree field of view. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04624.

- Kim, S.M.; Park, T.H.; Im, C.S.; Lee, S.S.; Kim, T.; Oh, M.C. Temporal response of polymer waveguide beam scanner with thermo-optic phase-modulator array. Opt. Express 2020, 28, 3768–3778.

- Sun, J.; Hosseini, E.; Yaacobi, A.; Cole, D.B.; Leake, G.; Coolbaugh, D.; Watts, M.R. Two-dimensional apodized silicon photonic phased arrays. Opt. Lett. 2014, 39, 367–370.

- Zadka, M.; Chang, Y.; Mohanty, A.; Phare, C.T.; Roberts, S.P.; Lipson, M. On-chip platform for a phased array with minimal beam divergence and wide field-of-view. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 2528–2534.

- Wang, P.; Luo, G.; Yu, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Zhang, Y.; Pan, J. Improving the performance of optical antenna for optical phased arrays through high-contrast grating structure on SOI substrate. Opt. Express 2019, 27, 2703–2712.

- Fatemi, R.; Khachaturian, A.; Hajimiri, A. A nonuniform sparse 2-D large-FOV optical phased array with a low-power PWM drive. IEEE J. Solid State Circuits 2019, 54, 1200–1215.

- Kim, S.H.; You, J.B.; Ha, Y.G.; Kang, G.; Lee, D.S.; Yoon, H.; Yoo, D.E.; Lee, D.W.; Yu, K.; Youn, C.H.; et al. Thermo-optic control of the longitudinal radiation angle in a silicon-based optical phased array. Opt. Lett. 2019, 44, 411–414.

- Gao, Y.; Lo, J.C.; Lee, S.; Patel, R.; Zhu, L.; Nee, J.; Tsou, D.; Carney, R.; Sun, J. High-power, narrow-linewidth, miniaturized silicon photonic tunable laser with accurate frequency control. J. Lightwave Technol. 2020, 38, 265–271.

- Liu, Y.; Hao, Z.; Wang, L.; Xiong, B.; Sun, C.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Han, Y.; Luo, Y. A single-chip multi-beam steering optical phased array: Design rules and simulations. Opt. Express 2021, 29, 7049–7059.

- Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, L. Bidirectional wide-angle waveguide grating antennas for optical phased arrays. To be submitted.

- Wang, C.; Zhang, M.; Chen, X.; Bertrand, M.; Ansari, A.; Chandrasekhar, S.; Winzer, P.; Lončar, M. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 2018, 562, 101–104.

- Wang, Y.; Liang, L.; Chen, Y.; Jia, P.; Qin, L.; Liu, Y.; Ning, Y.; Wang, L. Improved performance of optical phased arrays assisted by transparent graphene nanoheaters and air trenches. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 8442–8449.

- Hashemi, H. Monolithic optical phased arrays in silicon. In Proceedings of the 22nd Microoptics Conference (MOC), Tokyo, Japan, 19–22 November 2017.