Energetic materials are substances or mixtures in which, under the action of external forces, self-sustaining chemical reactions occur with the release of a large amount of energy. A promising group of energetic materials are reactive structural materials (RSMs), consisting of two or more solids, usually nonexplosive metallic or nonmetallic powders, in which an exothermic reaction can occur after high-velocity impact and penetration into a target. As a rule, thermite, intermetallic, metal-fluoropolymer systems and metastable intermixed composites are used as RSMs [1,2].

1. Introduction

Energetic materials can be used in the military field as kinetic penetrators, cumulative highly reactive fragments, shaped charge liners [1][3], reactive projectiles, and reactive (active) armor and munition bodies [2][3][4][1,2,4]. RSMs must have mechanical properties comparable to traditional materials, such as steel, aluminum, copper, etc., which have a tensile strength of no less than 100 MPa. The most promising in terms of high strength are intermetallic systems. The compositions of Ni–Al, Al–W, Al–Zr, etc., in addition to high energy concentration, possess structural strength [1][5][3,5]. Since RSM components, as a rule, are powders, they must be consolidated. There are various technologies to consolidate RSMs into a monolithic structure: radial forging [2][6][1,6], cold and hot isostatic pressing [7][8][7,8], high-pressure torsion [9], magnetron sputtering [10] and cold spraying [11][12][11,12], cold rolling [13][14][13,14], accumulative roll-bonding [15], and explosive compacting [5][16][5,16]. The disadvantages of sputtering are its low rate and high cost. High-pressure processing requires large-sized equipment and includes multi-stage plastic deformation of two materials with different plasticity, which can eventually lead to material cracking and partial chemical interaction between starting components.

In addition to consolidation, there are methods for strengthening metallic

[2][17][1,17], polymeric

[18], and cement matrices

[19], consisting of reinforcement with discrete

[20] or continuous fibers. Data on the reinforcement of powder materials with ordered continuous fibers to increase their strength are not available in the literature.

At present, there is an increased interest in works aimed at identifying the basic laws of interaction between metals and polymer matrices composed of polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) during heating

[21][22][21,22], shock-wave loading

[23][24][25][26][27][23,24,25,26,27], and dynamic and static loading

[28][29][30][31][28,29,30,31], with the variation in particle sizes

[32]. The effect of sintering temperature on the strength of Al–PTFE compacts was investigated in

[33]. In other works

[34][35][36][34,35,36], an aluminum honeycomb was used to increase the energy release and strength of Al–PTFE compacts. The increased interest of researchers in the Al–PTFE mixture is primarily due to the ability of PTFE to form chemical compounds containing Al. The enthalpy of reaction for the mixture with a ratio of 26.5% Al/73.5% PTFE with the formation of AlF

3 was estimated as −8.85 kJ/g, considering the enthalpy of PTFE decomposition (8 kJ/g) and the enthalpy of AlF

3 formation (−18 kJ/g)

[37]. The combustion heat per unit mass is 8.53 MJ/kg, which exceeds that of TNT more than twice

[38]. In

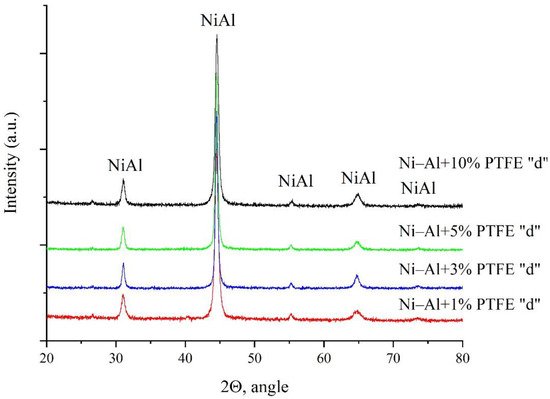

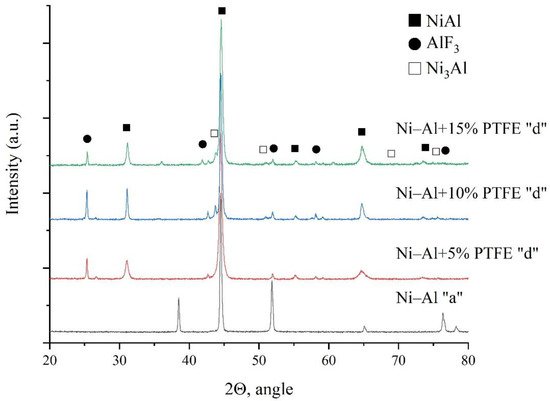

[39], it was found that the addition of PTFE reduces the critical initiation pressure in the Ni–Al intermetallic system.

Producing, testing, and studying promising RSMs with a certain set of physical and mechanical characteristics and high energy release are associated with several physical and chemical limitations and technological difficulties. Such studies, as a rule, are purely experimental and characterized by rapid physical and chemical processes, and high strain rates, pressures, and temperatures in reaction mixtures during explosive loading.

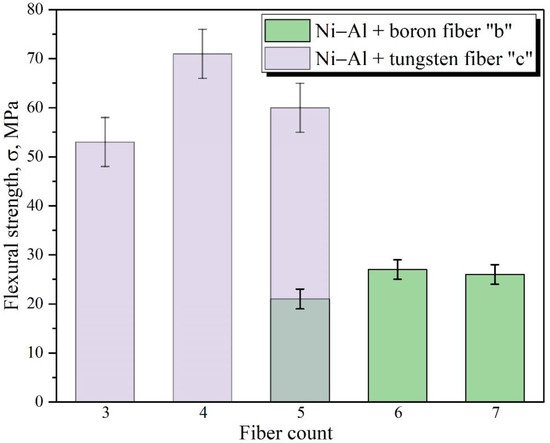

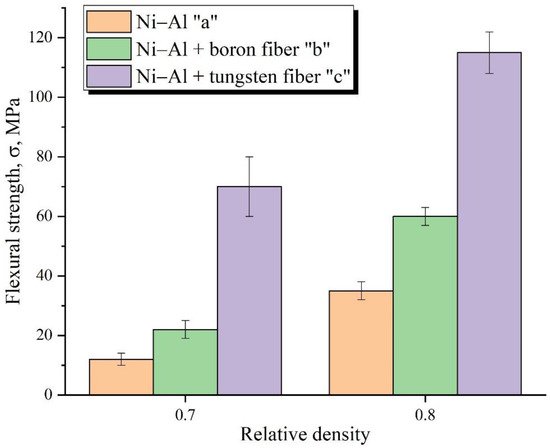

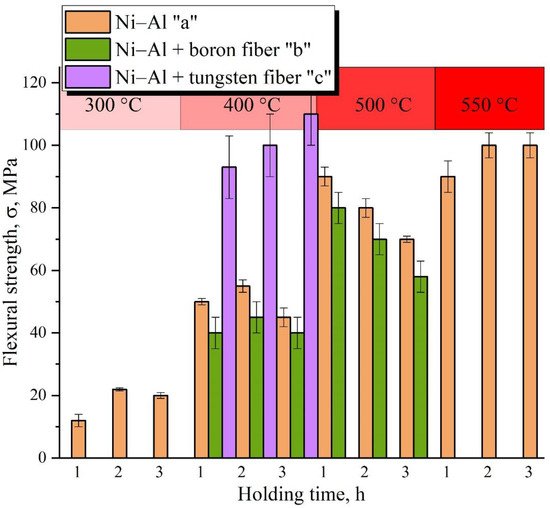

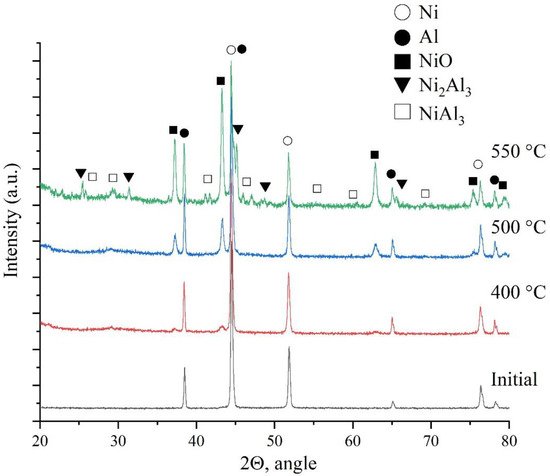

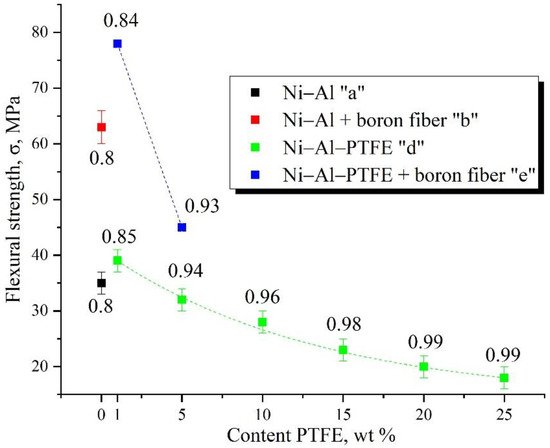

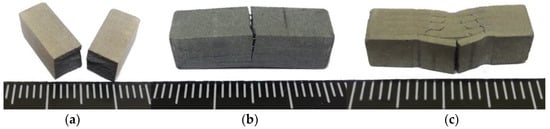

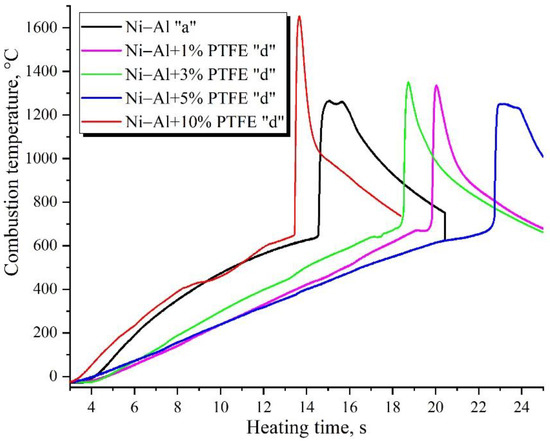

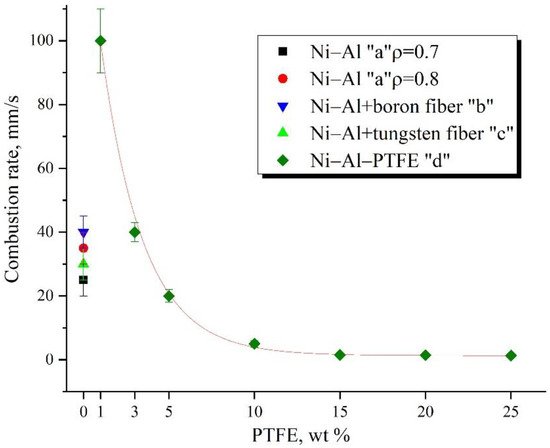

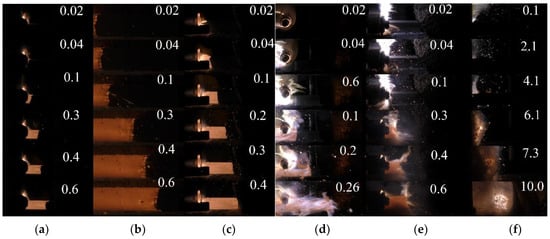

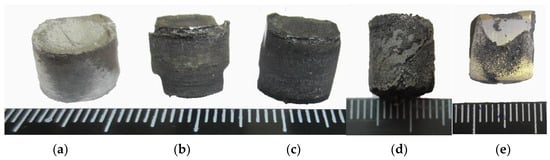

This paper presents studies of the strength, ignition, combustion, and shock-wave initiation of metal and metal-polymer powder mixtures based on Ni–Al and Ni–Al–PTFE. The effect of reinforcement with tungsten and boron fibers, low-temperature heat treatment (HT), and component fraction changes on the mechanical properties, phase formation, and energy characteristics of reactive powder compacts was investigated.