Colon capsule endoscopy is a safe diagnostic tool with low adverse event rates. As with other endoscopic modalities, various colon capsule endoscopy scores allow the standardisation of reporting and reproducibility. As bowel cleanliness affects CCE’s diagnostic yield, a few operator-dependent scores (Leighton–Rex and CC-CLEAR scores) and a computer-dependent score (CAC score) have been developed to grade bowel cleanliness objectively.

1. Introduction

The disruption brought about by the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a forward push with genuine innovation to expand healthcare services. Adjusting to curtailed nonemergency endoscopy services has led to a renewed interest in alternative modalities for colonic exploration, in an attempt to mitigate potential diagnostic delays. One such strategy to visualize the colon is by means of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE), which allows for a pain-free colonic assessment by eliminating the need for instrument insertion, gas insufflation or sedation [1,2]. This has allowed for the extension of CCE’s role in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in the average-risk population, as well as an alternative for patients who refuse optical colonoscopy (OC) or in whom the latter is contraindicated [3,4,5].

The disruption brought about by the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has led to a forward push with genuine innovation to expand healthcare services. Adjusting to curtailed nonemergency endoscopy services has led to a renewed interest in alternative modalities for colonic exploration, in an attempt to mitigate potential diagnostic delays. One such strategy to visualize the colon is by means of colon capsule endoscopy (CCE), which allows for a pain-free colonic assessment by eliminating the need for instrument insertion, gas insufflation or sedation [1][2]. This has allowed for the extension of CCE’s role in colorectal cancer (CRC) screening in the average-risk population, as well as an alternative for patients who refuse optical colonoscopy (OC) or in whom the latter is contraindicated [3][4][5].

In daily endoscopic practice, the use of various scores and scoring systems allow for the standardisation of reporting to increase objectivity, the reproducibility of findings and inter-observer agreement such as a description of lesions, mucosal disease activity and the adequacy of bowel preparation [6]. Eventually, the standardisation of reporting enables a higher quality of care and facilitates decision making and the continuity of care.

2. Bowel Cleanliness Scoring

The Boston Bowel Preparation Scale (BBPS) is a visual scale in which conventional colonoscopy images are rated according to a quantitative grading based on the aggregate of separate scores obtained from the right, transverse and left colon, respectively [7]. Each colonic segment is given a score from 0 to 3, with 0 denoting an unprepared colon segment in which the mucosa could not be visualised, due to solid stool which could not be cleared. A score of 1 denotes that a portion of the colonic mucosa could be seen; however, other areas were inadequately visualised because of residual stool, staining and/or opaque liquid. A score of 2 represents an adequately visualised colonic mucosa despite a minor residual staining, small stool fragments and/or opaque liquid. When the entire colonic mucosa within a segment is well visualised with no residual staining, small stool fragments or opaque liquid, a score of 3 is given.

In terms of CCE and detection of colorectal polyps and cancer, the sensitivity of CCE was significantly higher in patients with good or excellent colon cleanliness than in those with fair or poor colon cleanliness. The latter was determined using a four-point grading scale (Table 1), a global colonic assessment, as opposed to the segmental scoring approach present in the BBPS.

Table 1.

Grading of bowel cleanliness.

| A |

Large amount of faecal residue |

| B |

Enough faeces or dark fluid present to preclude a completely reliable examination |

| C |

Small amount of faeces or dark fluid, but not enough to interfere with examination |

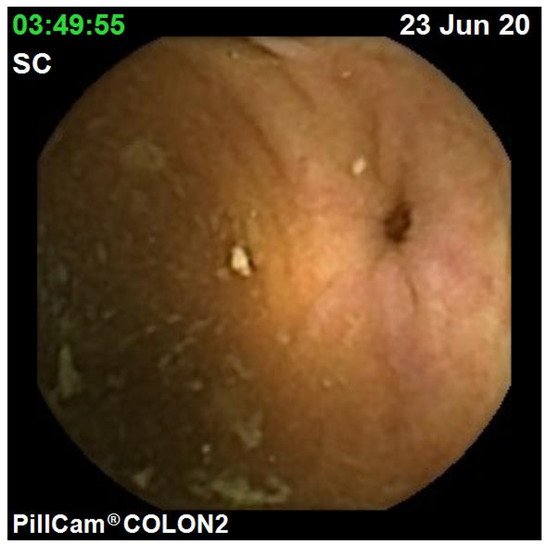

Colonic diverticulum.

2.1.1. Operator-Dependent Scores

The Leighton–Rex scale is a qualitative scale that divides the colon into five segments (caecum, right colon, transverse, left colon and rectum). The five segments are graded individually with regard to overall cleansing level and bubbles grading (Table 2).

Another operator-dependent bowel cleansing score is the Colon Capsule CLEansing Assessment and Report (CC-CLEAR). The CC-CLEAR interobserver agreement was superior to the Leighton–Rex scale (Kendall’s W 0.911 vs. 0.806, p < 0.01) [9].

| Inadequate. Large amount of faecal residue precludes a complete examination |

| Inadequate but examination completed. Enough faeces or turbid fluid to prevent a reliable examination |

| Adequate. Small amount of faeces or turbid fluid not interfering with examination |

| Adequate. No more than small bits of adherent faeces |

| Bubbles that interfere with the examination. More than 10% of surface area obscured by bubbles |

| No bubbles or bubbles that do not interfere with the examination. Less than 10% of surface area obscured by bubbles |

| D |

| No more than small bits of adherent faeces |

2.1. Colon Capsule Bowel Cleansing Scores

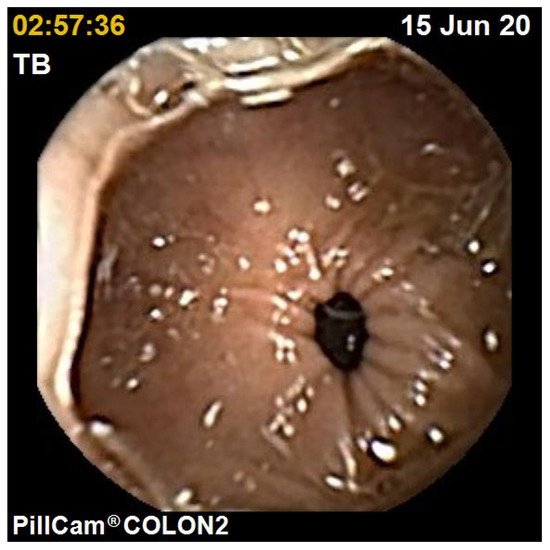

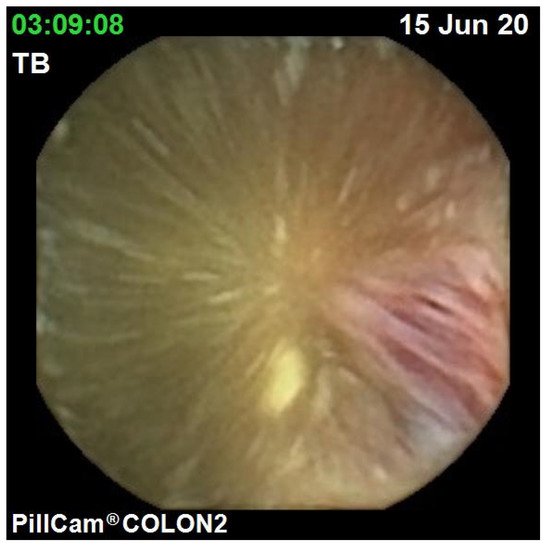

The diagnostic yield for CCE depends on two significant factors, including bowel preparation and image interpretation [10]. Similar to OC, CCE views allow for a detailed mucosal assessment. demonstrates a normal colonic mucosal appearance on CCE. Various pathologies apart from those mentioned in the scoring review can be detected, such as colonic angiodysplasias (), internal haemorrhoids (), and diverticula ().

The diagnostic yield for CCE depends on two significant factors, including bowel preparation and image interpretation [8]. Similar to OC, CCE views allow for a detailed mucosal assessment. Figure 1 demonstrates a normal colonic mucosal appearance on CCE. Various pathologies apart from those mentioned in the scoring review can be detected, such as colonic angiodysplasias (Figure 2), internal haemorrhoids (Figure 3), and diverticula (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Colonic diverticulum.

2.1.1. Operator-Dependent Scores

The Leighton–Rex scale is a qualitative scale that divides the colon into five segments (caecum, right colon, transverse, left colon and rectum). The five segments are graded individually with regard to overall cleansing level and bubbles grading ().

Another operator-dependent bowel cleansing score is the Colon Capsule CLEansing Assessment and Report (CC-CLEAR). The CC-CLEAR interobserver agreement was superior to the Leighton–Rex scale (Kendall’s W 0.911 vs. 0.806, p

2.1.2. Computer-Dependent Scores

An automated score, similar to that of Van Weyenberg et al. for the small bowel (SB), was developed: the colonic computed assessment of cleansing (CAC) score. This was based on a still frame colorimetric analysis of the tissue colour bar. The Pillcam

COLON-2 system was used. The CAC score, defined as the ratio of colour intensities, red over green (R/G ratio) and red over brown (R/(R + G) ratio), was calculated for extracted colonic frames. A threshold was applied and, thus, one was able to discriminate “adequately cleansed” from “inadequately cleansed” CCE still frames.

3. Mucosal Disease Activity in Inflammatory Bowel Disease

CCE is an effective tool to noninvasively assess mucosal disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), enabling the monitoring of response to treatment, determine mucosal healing, and surveillance.

3.1. Ulcerative Colitis

The CSUC score was developed using the collected CCE videos, which four blinded IBD experts scored. The descriptors validated with the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) were used as the candidate items, some of which were automatically assessed using the workstation. The UCEIS descriptors used in the CSUC score including vascular pattern (graded as normal, patchy obliteration and obliterated), bleeding (graded as none, mucosal, luminal mild, and luminal moderate or severe) and erosions and ulcers (graded as none, small erosions ≤ 5 mm, superficial ulcer ≥ 5 mm, and deep ulcer) [18] are shown in .

CCE is an effective tool to noninvasively assess mucosal disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), enabling the monitoring of response to treatment, determine mucosal healing, and surveillance.

3.1. Ulcerative Colitis

The CSUC score was developed using the collected CCE videos, which four blinded IBD experts scored. The descriptors validated with the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) were used as the candidate items, some of which were automatically assessed using the workstation. The UCEIS descriptors used in the CSUC score including vascular pattern (graded as normal, patchy obliteration and obliterated), bleeding (graded as none, mucosal, luminal mild, and luminal moderate or severe) and erosions and ulcers (graded as none, small erosions ≤ 5 mm, superficial ulcer ≥ 5 mm, and deep ulcer) [10] are shown in Table 3.

CSUS descriptors and definitions.

| Likert Scale Anchor Points |

|---|

| No visible blood detected by image reading software |

| No bleeding picture detected by image reading software ≤ 10 |

| No bleeding picture detected by image reading software > 10 |

| Normal mucosa, no visible erosions or ulcers |

| Tiny (≤5 mm) defects in the mucosa |

| Larger (>5 mm) defects in the mucosa |

| Larger (>5 mm) and deeper excavated defects in the mucosa, with a slightly raised edge |

3.2. Crohn’s Disease

The usefulness of CCE in Crohn’s disease (CD) remains unclear, contrasting with the established role of SB capsule endoscopy (SBCE) for the assessment of SB mucosal disease activity. In order to standardise the SB inflammatory burden in CD, two validated capsule endoscopy scores have been developed over the years, namely the Lewis score and the Capsule Endoscopy Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CECDAI or Niv score). The CECDAI evaluates three endoscopic parameters: inflammation severity, disease extent and presence of strictures.

With the current availability of Pillcam

COLON-2, which allows for the visualisation of colonic inflammatory disease activity, Niv et al. extended the validated CECDAI score to include the colon, introducing the novel CECDAIic score, allowing for an objective panenteric assessment of CD inflammatory activity (Table 4).

| Mild to moderate oedema/hyperaemia/denudation |

| Severe oedema/hyperaemia/denudation |

| Bleeding, exudate, aphthous ulcer, erosion and small ulcers (<0.5 cm) |

| Moderate ulcer (0.5–2 cm), pseudopolyp |

| Focal disease (single segment) |

| Patchy disease (multiple segments) |

Segmental score = A × B + C. Total score = (A1 × B1 + C1) + (A2 × B2 + C2) + (A3 × B3 + C3) + (A4 × B4 + C4). (1) Proximal small bowel; (2) Distal small bowel; (3) Right colon; (4) Left colon.

The role of identifying and removing adenomatous polyps during colonoscopy in the prevention of colorectal cancer is well-established. Poor adherence to OC by the screening population is an important limiting factor of screening colonoscopy due to its invasive nature and associated embarrassment. It also has a role in the detection or surveillance of colonic polyp(s) if the previous OC was incomplete or in the presence of severe medical co-morbidities where sedation would be deemed a high risk [11].

Various studies have demonstrated that CCE could visualize colonic segments missed by colonoscopy in 84.0–93.5% of patients [12][13][14][15][16].

The second-generation colon capsule, Pillcam

COLON-2, has demonstrated a much better performance in detecting colonic polyps. The integrated polyp size estimation tool within the RAPID software (Given

Imaging Ltd., Yokneam, Israel) when using Pillcam

COLON-2 allows the ease and reliability of measurement of polyp size in millimetres.

The use of OC as a CRC screening tool may be limited by the poor acceptance rate owing to patients’ concerns regarding its invasive nature, perceived lack of privacy, and potential adverse effects, together with logistical and financial implications from work-related absences [17]. CCE is an alternative investigation which could potentially mitigate such valid patient concerns, whilst still demonstrating comparable colonic polyp and CRC detection rates to OC as discussed previously [18]. Therefore, using CCE as a screening test for CRC could improve patient acceptance rates, whilst possibly reserving OC for therapeutic purposes. According to the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE), CCE can be used in average-risk patients for CRC screening and as an adjunctive test in patients with a prior incomplete OC, or in whom the latter is contraindicated or refused [19].

Beyond the realm of incomplete OC, CCE is also suitable for patients considered too high-risk for OC or unwilling to undergo OC. From a prospective study of 70 high-risk patients who had refused or were unable to undergo OC, CCE revealed significant findings in 34% of patients [20].