Stress is defined as a state of threatened or perceived as threatened homeostasis. Emerging evidence suggests that life-stress experiences can alter the epigenetic landscape and impact the function of genes involved in the regulation of stress response. More importantly, epigenetic changes induced by stressors persist over time, leading to increased susceptibility for a number of stress-related disorders.

- stress response

- glucocorticoids

- epigenetics

- stress-related disorders

1. Introduction

Stress is defined as a state of threatened or perceived as threatened homeostasis. A broad spectrum of extrinsic or intrinsic, real or perceived stressful stimuli, called ‘stressors’, activates a highly conserved system, the ‘stress system’, which adjusts homeostasis through central and peripheral neuroendocrine responses. The stress response depends on highly complex and tightly-regulated processes and involves the cross-talk of molecular, neuronal and hormonal circuits [1]. The well-tuned coordination of these systems is indispensable for an organism in order to adapt to stressors and re-establish homeostasis (adaptive stress response)

In mammals, glucocorticoid hormones are the main central effectors of the stress response, playing a crucial role in the effort of an organism to maintain its homeostasis during periods of stress [1]. Aberrant glucocorticoid signaling in response to stressors can lead to sub-optimal adaptation of an organism to stress events, a state that has been defined as cacostasis or allostasis [2]. When an organism falls into cacostasis, it strives to find ways to survive and maintain its stability outside of the normal homeostatic range, and the cost that it has to pay for this purpose is termed allostatic or cacostatic load [2].

Emerging evidence suggests that exposure to early-life stress events may alter the epigenomic landscape, which is defined as changes in the regulation of gene expression without changes to the DNA sequences [3]. The long-lasting nature of epigenetic changes led the scientific community to propose that glucocorticoid secretion in response to stress, as well as genes involved in the glucocorticoid signaling pathway, play a fundamental role in shaping a form of epigenetic memory through which stressful experiences become biologically embedded [3]. Critically, transcriptional dysregulation caused by aberrant epigenetic changes in glucocorticoid-related genes has been pathophysiologically linked with the emergence of a host of stress-related disorders [4].

2. Glucocorticoid Signaling via GRs and MRs upon Stress Response

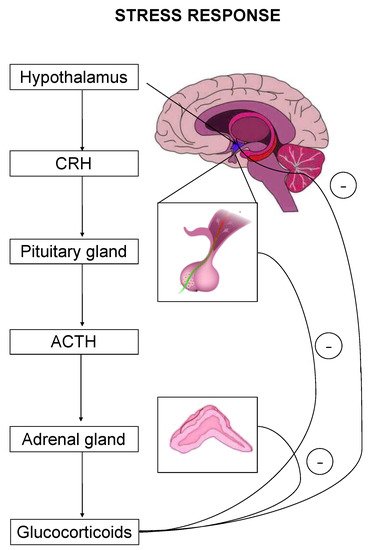

The stress response is primarily mediated by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis-, as well as by effectors acting on peripheral organs [2][5][6][7]. Upon stress-induced activation, the HPA axis stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) that drives the adrenal secretion of glucocorticoids in the blood circulation [8] (Figure 1). Glucocorticoids exert their effects on target organs mainly through binding and activation of two types of receptors, the mineralocorticoid (MR) and the glucocorticoid (GR) receptor [1].

Figure 1. The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is the primary effector of a stress response. Critical hormones and organs are shown, whereas cycles with the negative symbol indicate negative feedback mechanisms.

3. Functional Synergistic Network of MR and GR

MRs and GRs interact with each other throughout the stress response, mediating distinct but complementary roles, and their synergistic action is considered essential for the maintenance and/or restoration of homeostasis.

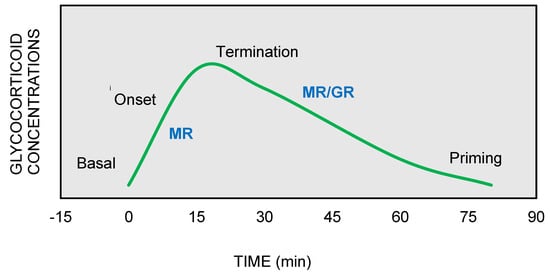

On the other hand, GRs are indispensable for the termination of stress response, the energy mobilization, the recovery, and the memory storage of stressful experiences for future purposes. It has been suggested that the stress response could be divided into four phases, based on spatiotemporal features of nongenomic and genomic GCs actions [9][10][11] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The stress response can be divided into four phases: (1) Basal: intracellular MRs are occupied with low concentrations of glucocorticoids (GCs). (2) Onset: GCs secretion from the adrenal cortex in response to a stressful event. GCs bind to MRs, which are progressively activated as the concentrations of GCs increase (3) Termination: GRs are activated and mediate the termination of stress response by exerting negative feedback at the hypothalamic and anterior pituitary level (4) Priming: Stressful experiences will be stored through GRs action in hippocampus and prefrontal context for future use.

MRs and GRs form a tightly co-regulated network that coordinates stress response and this observation led to the genesis of MR/GR balance hypothesis [11]. According to this hypothesis, an imbalance between the effects of GRs and MRs during the stress response may lead to dysregulation of the HPA axis and an inability to adapt to stressors and restore homeostasis, thereby conferring an increased vulnerability to a number of stress-related disorders [12].

4. Epigenetic Alterations as a Cause of Dysregulation of the Stress Response

An important mechanism that has been implicated in the development of MR/GR imbalance and HPA axis dysfunction pertains to the epigenetic alterations induced by major life stressors [13]. It has been proposed that epigenetic modifications can be a part of a memory system that stores and transmits information about past stressful experiences to progeny cells, thus shaping cellular responses to subsequent stressor stimuli [13].

The GR activation by GCs instigates not only changes in gene transcription upon stress, but also alterations in DNA methylation patterns, with the most preeminent change being the DNA demethylation at or near the GRE elements [3].

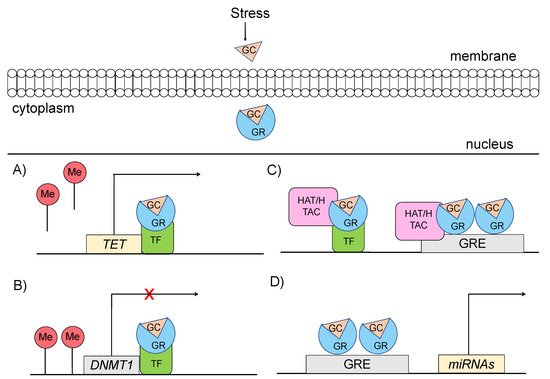

Specifically, glucocorticoids can shape the epigenome through four major mechanisms, which primarily involve GR signaling (Figure 3) [14][15]: (a) GCs can rapidly and dynamically evoke demethylation of cytosine-guanidine dinucleotides (CpGs) at or near GREs [3]. The mechanism behind this action implicates GC-dependent transcriptional upregulation of enzymes that catalyze active demethylation (ex. TET family of 5-methylcytosine dioxygenases), as well as downregulation of DNA methyltransferases (ex. DNA methyltransferase 1, DNMT1) [16]. Although GR signaling during stress has been generally associated with demethylation processes, the action of GRs has also been linked with methylation of a number of genes [17]; (b) GCs can induce histone modifications, such as methylation and acetylation of histone proteins, via direct GR binding or via interaction of GRs with other transcription factors (TFs) that recruit histone acetyltransferases [3]. For instance, the TF RelB/p52 has been shown to recruit CBP binding protein and HDAC deacetylase that promote acetylation and deacetylation of histone 3 Lys in the promoter regions of CRH and COX-2 genes [18]; (c) GCs can regulate expression patterns of several miRNAs, such as miR-218, miR-124, miR-29a, possibly through GR action, given that the genes encoding the altered miRNAs are enriched in predicted as GRE sites [19]; and (d) GCs can lead to chromatin remodeling via GR-activation, changing the accessibility of genomic regions to TFs [20].

Figure 3. Mechanisms through which glucocorticoid-mediated activation of GR can induce epigenetic changes (A) GRs through interaction with transcription factors (TF) catalyze active demethylation of enzymes involved in demethylation processes, such as the TET family of 5-methylcytosine dioxygenases. (B) GRs catalyze active methylation of enzymes involved in methylation processes, such as DNMT (DNA methyltransferase 1, DNMT1). (C) GRs activation can induce histone modifications via direct GR binding on GRE elements or via interaction of GRs with TFs that recruit histone acetyltransferases. (D) GRs activation can regulate the expression of microRNAs, enriched in GRE elements. GC: glucocorticoid, GR: glucocorticoid receptor, GRE: glucocorticoid response elements, DNMT1: DNA methyltransferase 1, HAT: histone acetyltransferases, HDAC: histone deacetylase, ME: methionine, TET: ten-eleven translocation methylcytosine dioxygenases, TF: transcription factor.

Epigenetic alterations induced by GCs can appear at specific genomic loci but also at the genome-wide level [3].

Epigenetic changes in response to exposure to stress in early life have also been documented in the human serotonin transporter (5-HTT), which is encoded by SLC6A4 gene and is considered to be a key regulator of the serotoninergic system that regulates the stress response [21]. In particular, early life adversities, such as childhood abuse, have been associated with increased methylation status of SLC6A4 at exon 1 [22][23].

Interestingly, epigenetic studies have demonstrated sex-dimorphic long-lasting methylation changes in various CpG sites of the oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) following early-life adverse events [24]. Specifically, exposure to adverse events during childhood and adolescence has been associated with higher methylation levels of CpG sites in OXTR gene only in females but not in males [24]. Summary of the most recent findings about epigenetic modifications upon stress exposure are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Summary of the most recent findings about epigenetic modifications upon stress exposure.

| Gene | Reference | Species | Stressors | Epigenetic Changes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FKBP5 | Saito et al., 2020 | [25] | Human | Childhood abuse | demethylation of FKBP5 intron 7 |

| Misiak et al., 2020 | [26] | Human | Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) | demethylation of FKBP5 | |

| Ramo-Fernandez et al., 2019 | [27] | Human | Childhood maltreatment | demethylation of FKBP5 | |

| NR3C1 | Borcoi et al., 2021 | [28] | Human | Food and nutritional security or insecurity status | hypermethylation of NR3C1 1F promoter |

| Pinheiro et al., 2021 | [29] | Human | Alcohol consumption, Body mass index—BMI | hypomethylation of NR3C1 1F promoter (alcohol consumption), hypermethylation of NR3C1 1F promoter (BMI) | |

| Misiak et al., 2021 | [30] | Human | Adverse childhood experiences | hypomethylation of NR3C1 | |

| BDNF | Duffy et al., 2020 | [31] | Rat | Aversive caregiving | hypermethylation BDNF |

| Blaze et al., 2017 | [32] | Rat | Caregiver maltreatment | hypermethylation BDNF IV | |

| Niknazar et al., 2017 | [33] | Rat | Preconception maternal stress | hypermethylation BDNF | |

| SLC6A4 | Delano et al., 2021 | [34] | Human | Maternal community-level deprivation | hypermethylation of 8 CpGs SLC6A4 |

| Anurag et al., 2019 | [35] | Human | Early adversity (children of alcoholics) | hypermethylation of SLC6A4 | |

| Smith et al., 2017 | [36] | Human | Adverse neighborhood environment | hypermethylation of SLC6A4 | |

| OXTR | Kogan et al., 2019 | [37] | Human | Childhood adversity and socioeconomic instability | hypermethylation of OXTR |

| Kogan et al., 2018 | [38] | Human | Childhood adversity | hypermethylation of OXTR | |

| Gouin et al., 2017 | [39] | Human | Early life adversity (ELA) | hypermethylation of OXTR in females |

5. Epigenetic Changes and Stress-Related Disorders

Epigenetic modifications constitute part of a mechanism through which stressful life experiences are embedded in an individual’s biology, shaping the response to future threats [13]. More importantly, epigenetic changes have the intrinsic feature to persist over time, with a growing number of studies suggesting that they may predispose an individual to the development of stress-related phenotypes and diseases [13].

The interplay between genetic background-epigenetic environment seems to be more relevant during critical developmental periods where the epigenome shows heightened plasticity, such as in childhood, adolescence, or later life, since no association among them has been reported during adulthood [40].

Studies exploring methylation changes inNR3C1, have investigated the effect of life-stress experiences occurring at different time periods, from as early as prenatal life to childhood and adulthood [41]. The majority of these studies reported significant hypermethylation at the exon 1F promoter ofNR3C1, which was also positively associated with the severity and the duration of an adverse event [42]. It has been proposed thatNR3C1hypermethylation act as a mediator of the association between early life adversity and stress-related disorders [42]. In particular, prenatal stress due to maternal depression and early prenatal loss has been associated with hypermethylation of CpG sites from 35 to 37, at hGR 1F promoter, triggering the development of depression, bipolar disorder and suicidal behavior later in life [43].

Recent studies in animal models of stress and depression revealed a decrease in Bdnf hippocampal mRNA levels, mediated by long-lasting methylation and acetylation changes in the promoter regions ofBdnfthat were induced from perinatal exposure to methylmercury [44] or chronic social defeat stress conditions [45][46]. Moreover, in patients with depression, there was a significant decrease in BNDF protein levels compared to controls [47], while administration of antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, stimulatedBDNFexpression and reversed the symptoms of depression [48].

Major depressive disorder has also been associated with increased methylation levels ofSLC6A2[49] in subjects with a history of exposure to stress early in life, such as childhood maltreatment (CM) [23] or low socioeconomic status (SES) during adolescence [50]. In particular, greater methylation levels of CpG sites 11 and 12 of SLC6A2 gene were reported in individuals with a CM history [23] and greater methylation levels ofSLC6A2promoter were reported in individuals with a history of low SES during adolescence [50]. Both methylation patterns were associated with the emergence of depressive symptoms later in life [23][50].

The OXTR protein plays an important role in the regulation of social cognition (feelings of attachment and social recognition), as well as in the regulation of anxiety-related and social behaviors [51]. In female subjects, adverse events in adulthood (financial pressure, high crime neighborhood) may induce methylation pattern changes inOXTRand may increase vulnerability to depression [52]. Furthermore, early traumatic events in childhood have been associated with altered methylation status ofOXTRthat may mediate the development of mood disorders in adulthood More specifically, hypomethylation of CpGs located in the promoter region ofOXTRexon 1 and hypermethylation of sites located inOXTRintron 3 have been associated with depression and anxiety disorders in subjects with a history of childhood abuse [53].

6. Summary

Compelling evidence suggests that epigenetic modifications in stress-related genes involved in glucocorticoid signaling represent a mechanism through which stress-related experiences are embedded in an individual’s biology. Epigenetic changes can influence the subsequent coping strategies [54] to stressors and, when accumulated, can contribute to the development of stress-related disorders [13]. A number of studies, claimed that epigenetic changes can actually be inherited to the next generation and as such parent’s stressful experiences could influence offspring’s vulnerability to many pathological conditions [55][56][57][58]. However, many researchers are sceptical about the potential of trauma inheritance through epigenome [59] and also highlight the need to perform epigenetic studies taking into account an individual’s genetic background [60][61].

The imperfect fit of different epigenetic studies that follow a traditional reductionist paradigm, suggests that the interaction of stressors with the epigenome and its implication in the emergence of stress-related disorders is a much more complex network than previously thought, and demands our investigation in a context-specific and time-dependent manner. We hope that this article will help future studies, to build upon existing and novel findings their design, taking into account confounders that may bias study results, in order to delineate the mechanism linking stress exposure to epigenome and stress-related disorders development via the action of GCs.

References

- Charmandari, E.; Tsigos, C.; Chrousos, G. Endocrinology of the stress response. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2005, 67, 259–284.

- Chrousos, G.P. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2009, 5, 374–381.

- Zannas, A.S.; Chrousos, G.P. Epigenetic programming by stress and glucocorticoids along the human lifespan. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 640–646.

- Dupont, C.; Armant, D.R.; Brenner, C.A. Epigenetics: Definition, Mechanisms and Clinical Perspective. Semin. Reprod. Med. 2009, 27, 351–357.

- Habib, K.E.; Gold, P.W.; Chrousos, G.P. Neuroendocrinology of stress. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2001, 30, 695–728.

- Chrousos, G.P. Regulation and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. The corticotropin-releasing hormone perspective. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 1992, 21, 833–858.

- Whitnall, M.H. Regulation of the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone neurosecretory system. Prog. Neurobiol. 1993, 40, 573–629.

- Nicolaides, N.C.; Kyratzi, E.; Lamprokostopoulou, A.; Chrousos, G.P.; Charmandari, E. Stress, the stress system and the role of glucocorticoids. Neuroimmunomodulation 2015, 22, 6–19.

- MR/GR Signaling in the Brain during the Stress Response|IntechOpen. Available online: (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- De Kloet, E.R.; Joëls, M.; Holsboer, F. Stress and the brain: From adaptation to disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2005, 6, 463–475.

- De Kloet, E.R.; Meijer, O.C.; de Nicola, A.F.; de Rijk, R.H.; Joëls, M. Importance of the brain corticosteroid receptor balance in metaplasticity, cognitive performance and neuro-inflammation. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 124–145.

- De Kloet, E.R.; Meijer, O.C. MR/GR Signaling in the Brain during the Stress Response. Aldosterone-Miner. Recept Cell Biol. Transl. Med. 2019.

- Gassen, N.C.; Chrousos, G.P.; Binder, E.B.; Zannas, A.S. Life stress, glucocorticoid signaling, and the aging epigenome: Implications for aging-related diseases. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 74 Pt B, 356–365.

- Bagot, R.C.; Labonté, B.; Peña, C.J.; Nestler, E.J. Epigenetic signaling in psychiatric disorders: Stress and depression. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2014, 16, 281–295.

- Alyamani, R.A.S.; Murgatroyd, C. Epigenetic Programming by Early-Life Stress. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 2018, 157, 133–150.

- Wiechmann, T.; Röh, S.; Sauer, S.; Czamara, D.; Arloth, J.; Ködel, M.; Beintner, M.; Knop, L.; Menke, A.; Binder, E.B.; et al. Identification of dynamic glucocorticoid-induced methylation changes at the FKBP5 locus. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 83.

- Park, C.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Brietzke, E.; Pan, Z.; Lee, Y.; Cao, B.; Zuckerman, H.; Kalantarova, A.; McIntyre, R.S. Stress, epigenetics and depression: A systematic review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 102, 139–152.

- Uht, R.M. Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Receptor (GR) Mediated Corticotropin Releasing Hormone Gene Expression. Glucocorticoids New Recognit. Fam. Friend 2012.

- Dwivedi, Y.; Roy, B.; Lugli, G.; Rizavi, H.; Zhang, H.; Smalheiser, N.R. Chronic corticosterone-mediated dysregulation of microRNA network in prefrontal cortex of rats: Relevance to depression pathophysiology. Transl. Psychiatry 2015, 5, e682.

- Vockley, C.M.; D’Ippolito, A.M.; McDowell, I.C.; Majoros, W.H.; Safi, A.; Song, L.; Crawford, G.E.; Reddy, T.E. Direct GR binding sites potentiate clusters of TF binding across the human genome. Cell 2016, 166, 1269–1281.e19.

- Provenzi, L.; Giorda, R.; Beri, S.; Montirosso, R. SLC6A4 methylation as an epigenetic marker of life adversity exposures in humans: A systematic review of literature. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 71, 7–20.

- Kang, H.-J.; Kim, J.-M.; Stewart, R.; Kim, S.-Y.; Bae, K.-Y.; Kim, S.-W.; Shin, I.-S.; Shin, M.-G.; Yoon, J.-S. Association of SLC6A4 methylation with early adversity, characteristics and outcomes in depression. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 44, 23–28.

- Booij, L.; Szyf, M.; Carballedo, A.; Frey, E.-M.; Morris, D.; Dymov, S.; Vaisheva, F.; Ly, V.; Fahey, C.; Meaney, J.; et al. DNA methylation of the serotonin transporter gene in peripheral cells and stress-related changes in hippocampal volume: A study in depressed patients and healthy controls. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0119061.

- Kraaijenvanger, E.J.; He, Y.; Spencer, H.; Smith, A.K.; Bos, P.A.; Boks, M.P.M. Epigenetic Variability in the Human Oxytocin Receptor (OXTR) Gene: A Possible Pathway from Early Life Experiences to Psychopathologies. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 96, 127–142.

- Saito, T.; Shinozaki, G.; Koga, M.; Tanichi, M.; Takeshita, S.; Nakagawa, R.; Nagamine, M.; Cho, H.R.; Morimoto, Y.; Kobayashi, Y.; et al. Effect of interaction between a specific subtype of child abuse and the FKBP5 rs1360780 SNP on DNA methylation among patients with bipolar disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 2020, 272, 417–422.

- Misiak, B.; Karpiński, P.; Szmida, E.; Grąźlewski, T.; Jabłoński, M.; Cyranka, K.; Rymaszewska, J.; Piotrowski, P.; Kotowicz, K.; Frydecka, D. Adverse Childhood Experiences and Methylation of the FKBP5 Gene in Patients with Psychotic Disorders. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 3792.

- Ramo-Fernández, L.; Boeck, C.; Koenig, A.M.; Schury, K.; Binder, E.B.; Gündel, H.; Fegert, J.M.; Karabatsiakis, A.; Kolassa, I.-T. The effects of childhood maltreatment on epigenetic regulation of stress-response associated genes: An intergenerational approach. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9.

- Borçoi, A.R.; Mendes, S.O.; Moreno, I.A.A.; Gasparini Dos Santos, J.; Freitas, F.V.; Pinheiro, J.A.; de Oliveira, M.M.; Barbosa, W.M.; Arpini, J.K.; Archanjo, A.B.; et al. Food and nutritional insecurity is associated with depressive symptoms mediated by NR3C1 gene promoter 1F methylation. Stress 2021, 1–8.

- De Assis Pinheiro, J.; Freitas, F.V.; Borçoi, A.R.; Mendes, S.O.; Conti, C.L.; Arpini, J.K.; Dos Santos Vieira, T.; de Souza, R.A.; Dos Santos, D.P.; Barbosa, W.M.; et al. Alcohol consumption, depression, overweight and cortisol levels as determining factors for NR3C1 gene methylation. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6768.

- Misiak, B.; Samochowiec, J.; Konopka, A.; Gawrońska-Szklarz, B.; Beszłej, J.A.; Szmida, E.; Karpiński, P. Clinical correlates of the NR3C1 gene methylation at various stages of psychosis. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020, 24.

- Duffy, H.B.D.; Roth, T.L. Increases in Bdnf DNA Methylation in the Prefrontal Cortex Following Aversive Caregiving Are Reflected in Blood Tissue. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 594244.

- Blaze, J.; Roth, T.L. Caregiver maltreatment causes altered neuronal DNA methylation in female rodents. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 477–489.

- Niknazar, S.; Nahavandi, A.; Peyvandi, A.A.; Peyvandi, H.; Zare Mehrjerdi, F.; Karimi, M. Effect of Maternal Stress Prior to Conception on Hippocampal BDNF Signaling in Rat Offspring. Mol. Neurobiol. 2017, 54, 6436–6445.

- DeLano, K.; Folger, A.T.; Ding, L.; Ji, H.; Yolton, K.; Ammerman, R.T.; Van Ginkel, J.B.; Bowers, K.A. Associations Between Maternal Community Deprivation and Infant DNA Methylation of the SLC6A4 Gene. Front. Public Health 2020, 8.

- Timothy, A.; Benegal, V.; Shankarappa, B.; Saxena, S.; Jain, S.; Purushottam, M. Influence of early adversity on cortisol reactivity, SLC6A4 methylation and externalizing behavior in children of alcoholics. Prog. Neuro-Psychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2019, 94.

- Smith, J.A.; Zhao, W.; Wang, X.; Ratliff, S.M.; Mukherjee, B.; Kardia, S.L.R.; Liu, Y.; Roux, A.V.D.; Needham, B.L. Neighborhood characteristics influence DNA methylation of genes involved in stress response and inflammation: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Epigenetics 2017, 12, 662–673.

- Kogan, S.M.; Bae, D.; Cho, J.; Smith, A.K.; Nishitani, S. Childhood Adversity, Socioeconomic Instability, Oxytocin-Receptor-Gene Methylation, and Romantic-Relationship Support Among Young African American Men. Psychol. Sci. 2019, 30, 1234–1244.

- Kogan, S.M.; Cho, J.; Beach, S.R.H.; Smith, A.K.; Nishitani, S. Oxytocin receptor gene methylation and substance use problems among young African American men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018, 192, 309–315.

- Gouin, J.P.; Zhou, Q.Q.; Booij, L.; Boivin, M.; Côté, S.M.; Hébert, M.; Ouellet-Morin, I.; Szyf, M.; Tremblay, R.E.; Turecki, G.; et al. Associations among oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) DNA methylation in adulthood, exposure to early life adversity, and childhood trajectories of anxiousness. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7.

- Klengel, T.; Binder, E.B. Allele-specific epigenetic modification: A molecular mechanism for gene–environment interactions in stress-related psychiatric disorders? Epigenomics 2013, 5, 109–112.

- Daskalakis, N.P.; Yehuda, R. Site-specific methylation changes in the glucocorticoid receptor exon 1F promoter in relation to life adversity: Systematic review of contributing factors. Front. Neurosci. 2014, 8.

- Cicchetti, D.; Handley, E.D. Methylation of the glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) in maltreated and nonmaltreated children: Associations with behavioral undercontrol, emotional lability/negativity, and externalizing and internalizing symptoms. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 1795–1806.

- Palma-Gudiel, H.; Córdova-Palomera, A.; Leza, J.C.; Fañanás, L. Glucocorticoid receptor gene (NR3C1) methylation processes as mediators of early adversity in stress-related disorders causality: A critical review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2015, 55, 520–535.

- Onishchenko, N.; Karpova, N.; Sabri, F.; Castrén, E.; Ceccatelli, S. Long-lasting depression-like behavior and epigenetic changes of BDNF gene expression induced by perinatal exposure to methylmercury. J. Neurochem. 2008, 106, 1378–1387.

- Tsankova, N.M.; Berton, O.; Renthal, W.; Kumar, A.; Neve, R.L.; Nestler, E.J. Sustained hippocampal chromatin regulation in a mouse model of depression and antidepressant action. Nat. Neurosci. 2006, 9, 519–525.

- Miao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Z. The Relationships Between Stress, Mental Disorders, and Epigenetic Regulation of BDNF. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1375.

- Dwivedi, Y.; Rizavi, H.S.; Conley, R.R.; Roberts, R.C.; Tamminga, C.A.; Pandey, G.N. Altered gene expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and receptor tyrosine kinase B in postmortem brain of suicide subjects. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 2003, 60, 804–815.

- Molendijk, M.; Bus, B.A.; Spinhoven, P.; Penninx, B.W.; Kenis, G.; Prickaerts, J.; Voshaar, R.O.; Elzinga, B. Serum levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in major depressive disorder: State-trait issues, clinical features and pharmacological treatment. Mol. Psychiatry 2011, 16, 1088–1095.

- Silva, R.C.; Maffioletti, E.; Gennarelli, M.; Baune, B.T.; Minelli, A. Biological correlates of early life stressful events in major depressive disorder. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2021, 125, 105103.

- Swartz, J.R.; Hariri, A.R.; Williamson, D.E. An epigenetic mechanism links socioeconomic status to changes in depression-related brain function in high-risk adolescents. Mol. Psychiatry 2017, 22, 209–214.

- Maud, C.; Ryan, J.; McIntosh, J.E.; Olsson, C.A. The role of oxytocin receptor gene (OXTR) DNA methylation (DNAm) in human social and emotional functioning: A systematic narrative review. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18.

- Simons, R.L.; Lei, M.K.; Beach, S.R.H.; Cutrona, C.E.; Philibert, R.A. Methylation of the oxytocin receptor gene mediates the effect of adversity on negative schemas and depression. Dev. Psychopathol. 2017, 29, 725–736.

- Smearman, E.L.; Almli, L.M.; Conneely, K.N.; Brody, G.H.; Sales, J.M.; Bradley, B.; Ressler, K.J.; Smith, A.K. Oxytocin Receptor Genetic and Epigenetic Variations: Association With Child Abuse and Adult Psychiatric Symptoms. Child. Dev. 2016, 87, 122–134.

- Shirata, T.; Suzuki, A.; Matsumoto, Y.; Noto, K.; Goto, K.; Otani, K. Interrelation between increased bdnf gene methylation and high sociotropy, a personality vulnerability factor in cognitive model of depression. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2020, 16, 1257–1263.

- Schiele, M.A.; Gottschalk, M.G.; Domschke, K. The applied implications of epigenetics in anxiety, affective and stress-related disorders—A review and synthesis on psychosocial stress, psychotherapy and prevention. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 77, 101830.

- Yehuda, R.; Daskalakis, N.P.; Bierer, L.M.; Bader, H.N.; Klengel, T.; Holsboer, F.; Binder, E.B. Holocaust Exposure Induced Intergenerational Effects on FKBP5 Methylation. Biol. Psychiatry 2016, 80, 372–380.

- Pang, T.Y.C.; Short, A.K.; Bredy, T.W.; Hannan, A.J. Transgenerational paternal transmission of acquired traits: Stress-induced modification of the sperm regulatory transcriptome and offspring phenotypes. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 2017, 14, 140–147.

- Saavedra-Rodríguez, L.; Feig, L.A. Chronic social instability induces anxiety and defective social interactions across generations. Biol. Psychiatry 2013, 73, 44–53.

- Why I’m Sceptical about the Idea of Genetically Inherited Trauma. The Guardian, 11 September 2015. Available online: (accessed on 16 May 2021).

- Birney, E. Chromatin and heritability: How epigenetic studies can complement genetic approaches. Trends Genet. TIG 2011, 27, 172–176.

- Relton, C.L.; Smith, G.D. Epigenetic Epidemiology of Common Complex Disease: Prospects for Prediction, Prevention, and Treatment. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000356.