Electrogenic microorganisms possess unique redox biological features, being capable of performing Extracellular Electron Transfer (EET) and converting highly toxic compounds into nonhazardous forms. These microorganisms have led to the development of Microbial Electrochemical Technologies (METs), which include applications in the fields of bioremediation and bioenergy production. Geobacter bacteria have served as a model for understanding the mechanisms underlying the phenomenon of EET, which is highly dependent on a multitude of multiheme cytochromes (MCs). MCs are, therefore, logical targets for rational protein engineering to improve the EETextracellular electron transfer rates of these bacteria. In this Review, the main characteristics of electroactive Geobacter bacteria, their potential to develop METs and the main features of MCs are initially highlighted. This is followed by a detailed description of the current methodologies that assist the characterization of the functional redox networks in MCs. Finally, it is discussed how this information can be explored to design optimal Geobacter-mutated strains with improved capabilities in METs.

- electroactive microorganisms

- Microbial Electrochemical Technologies (METs)

- bioenergy production

- bioremediation

- protein engineering

- multiheme cytochromes

- redox characterization

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR)

1. Introduction

Electroactive microorganisms have been extensively studied since their discovery more than a century ago [1] and are defined by their ability to exchange electrons between intracellular donors and extracellular acceptors [2], a phenomenon designated Extracellular Electron Transfer (EET). These microorganisms span all three domains of life (Archaea, Bacteria and Eukarya) and are capable of producing electrical current and transferring electrons to different electrode surfaces in a multitude of bioelectrochemical devices [2]. Electroactive microorganisms have developed metabolic features that allow them to thrive in extreme environments, using toxic and radioactive compounds as terminal electron acceptors [3]. These features make them interesting targets for Microbial Electrochemical Technologies (METs), ranging from bioenergy production [4][5] and bioremediation applications [3][6], to the fields of bioelectronics [7][8] and bionanotechnology [9].

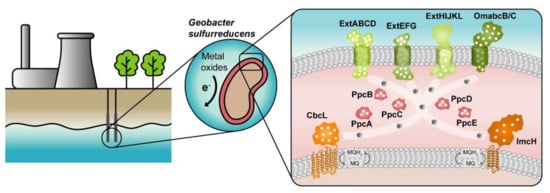

The highest current densities recorded to date in METs come from mixed cultures that are usually dominated by Deltaproteobacteria of the genus Geobacter [2], such as G. sulfurreducens, making them the most often selected microbial catalyst for such applications. G. sulfurreducens was firstly classified as a strict anaerobe naturally found in a variety of soils and sediments. Later, it was discovered that it could withstand low levels of molecular oxygen, providing an explanation for its abundance in oxic subsurface environments [10]. This bacterium is able to reduce a large variety of extracellular compounds, including Fe(III), U(VI) and Mn(IV) oxides, as well as many toxic organic substances that contaminate soils and wastewaters [11] and for this reason, Geobacter is being explored in bioremediation technologies (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Geobacter-based bioremediation technologies and current model for EET in G. sulfurreducens. A conceptual bioremediation station installed near soils, sediments and groundwater contaminated by industrial activities is represented. In this station, organic carbon compounds are introduced to native microorganisms, such as G. sulfurreducens, through injection wells (see [12]). This bacterium couples the oxidation of those compounds with the reduction of different toxic or radioactive compounds, leading to their precipitation and thus facilitating their removal. On the right panel, a model for the EET pathways of G. sulfurreducens is presented. The different proteins that play a role in EET spread from the inner membrane (CbcL and ImcH in orange), through the periplasm (PpcA-family in pink), and to the outer membrane (porin-cytochrome complexes in green). Heme groups are represented in white.

The cytochromes from G. sulfurreducens are localized at the bacterium’s inner membrane, periplasm and outer membrane, allowing the transfer of electrons from intracellular carriers, such as NADH, to extracellular acceptors.

The suggested model (Figure 1) highlights the importance of MCs in the EET mechanisms of G. sulfurreducens. They are logical targets for rational protein engineering focusing on the tuning of their redox properties, resulting in improved forms of these electron transfer components. A rational-mutated Geobacter strain, containing several optimized EET components and increased respiratory rates, can putatively contribute to more efficient METs.

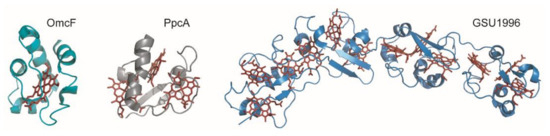

Cytochromes c are proteins containing one or several c-type heme groups that often function as electron carriers in biological systems (Figure 2) [13][14].

Figure 2. Structures of different c-type cytochromes from G. sulfurreducens obtained in the oxidized state. Monoheme OmcF (PDB ID: 3CU4 [15]), triheme PpcA (lowest energy, PDB ID: 2MZ9 [16]) and dodecaheme GSU1996 (PDB ID: 3OV0 [17]). In all structures, the heme groups are represented in red.

Several strategies have been developed to characterize MCs, both functionally and structurally [18][19][20][21][22][23]. These strategies have been useful to reveal the functional mechanisms and key residues involved in the redox reactions of these proteins. The knowledge obtained from such studies is currently being explored to design Geobacter strains with higher EET efficiency and to improve Geobacter-based biotechnological applications.

2. Modulation of the Redox Properties of MC for Optimized Geobacter Strains

2.1. Enginnering of MCs—The Example of PpcA Mutants

The engineering of MCs is one of the strategies that may contribute to improve current production by electrogenic bacteria, either by increasing the bacterium’s biomass formation or by optimizing the bacterium’s electron transfer mechanisms. In the first case, mutants with enhanced e−/H+ mechanism, contributing to increased membrane potential and ATP production, can be envisaged. In the second case, the design of periplasmic proteins, with enhanced electron-transfer driving force for either upstream or downstream partners, will contribute to the creation of Geobacter cells with improved electron transfer capabilities.

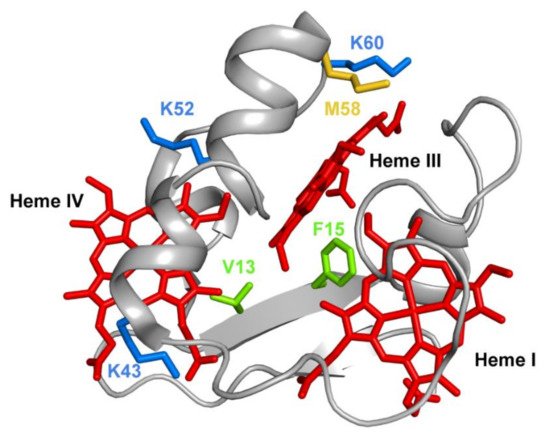

The redox properties of the heme groups of MCs can be modulated considering different structural aspects, including intrinsic properties of the heme cofactors and those of the neighbor residues. Mutations can be designed to explore different chemical properties, including the heme’s solvent exposure and network of interactions, such as surrounding hydrogen bonds and ionizable residues. Therefore, depending on the location and nature of the targeted residue, different strategies can be applied.

Several mutations were carried out in strategic regions of the protein (Figure 3) and included replacements in (i) conserved residues found in the PpcA-family of cytochromes (V13 and F15), (ii) a residue that controls heme III’s solvent accessibility (M58) and (iii) positively charged lysine residues in the vicinity of the hemes (K43, K52 and K60).

Figure 3. The spatial location of the residues mutated in the PpcA solution structure. The PpcA polypeptide chain (PDB code: 2MZ9 [16]) is shown as a Cα ribbon in gray, with the heme groups in red. The side chains of V13 and F15 are represented in green; K43, K52 and K60 in blue; and M58 in yellow, all in stick drawings.

2.2. In Vivo Testing of the Impact of the Selected Mutations of PpcA

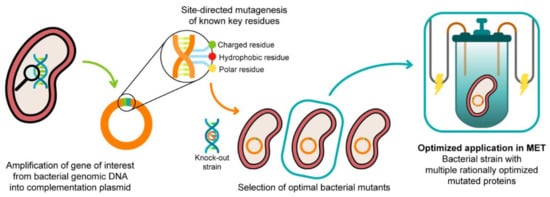

In 2003, Lloyd and co-workers [24] used a G. sulfurreducens strain with the ppcA gene knocked out to show that the bacterial growth with fumarate as an electron acceptor is not affected, while the growth rate significantly decreased when Fe(III) citrate was used as an electron acceptor. The ability of the bacterium to grow with Fe(III) citrate was restored when PpcA was expressed in trans from a complementation plasmid inserted by electroporation [24]. A similar strategy (Figure 4) can be envisaged to probe the effects of the PpcA mutants [25][24], using either the G. sulfurreducens strain with the ppcA gene knocked out [24] or, ideally, a G. sulfurreducens strain with all five cytochromes from the PpcA-family knocked out [26], to allow a more straightforward interpretation of results caused by the expression of the mutated forms of PpcA.

Figure 4. A schematic representation of the preparation of G. sulfurreducens strains with mutated cytochromes. After the bacterial genome is extracted, the specific target gene is amplified and further inserted into a complementation plasmid. The gene is mutated in key residues through site-directed mutagenesis, and the resultant mutants are inserted into a bacterial knock-out strain. The EET capabilities of the engineered bacteria are then tested in media with different electron acceptors. This process is applied to different key EET components of the bacterium, and the optimized mutants are selected and conjugated. The resultant strain, with higher electron transfer driving force and current production, is finally applied in METs.

2.3. Ongoing Biotic Strategies to Improve Extracellular Electron Transfer

The protein engineering of cytochromes can be explored as such or to complement other biotic approaches that already led to an increase in the electron transfer efficiency of electroactive microorganisms. Yi and co-workers [27] showed that appropriate selective pressures in these microorganisms could lead to the development of new strains with enhanced capacity for current production in MFC’s. In their work, a wild-type strain of G. sulfurreducens was inoculated in a system in which a graphite anode was poised at −400 mV (versus Ag/AgCl) for 5 months, from which an isolate, designated strain KN400, was later recovered. This strain possessed several phenotypic changes in the outer surface of the cell, namely a higher abundance of protein nanowires, pili and flagella, which resulted in higher current and power densities than the wild-type strain. Jensen and co-workers [28] used a synthetic-biology approach to engineer a microorganism to increase its EET properties. By inserting the porin-cytochrome outer membrane MtrCAB complex of Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 into Escherichia coli, they were able to significantly increase the capacity of the latter to reduce metal ions and solid metal oxides. More recently, Ueki and co-workers [26] trimmed the redundancy of G. sulfurreducens EET pathways by creating a strain with minimal requirements. This “stripped-down” strain, with well-defined EET pathways, constitutes an excellent vehicle to implement the protein-engineering strategies described in this Review, allowing the design of strains with optimal EET mechanisms.

References

- Potter, M.C. Electrical effects accompanying the decomposition of organic compounds. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Contain. Pap. Biol. Character 1911, 84, 260–276.

- Logan, B.E.; Rossi, R.; Saikaly, P.E. Electroactive microorganisms in bioelectrochemical systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 307–319.

- Wang, X.; Aulenta, F.; Puig, S.; Esteve-Núñez, A.; He, Y.; Mu, Y.; Rabaey, K. Microbial electrochemistry for bioremediation. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2020, 1, 100013.

- Arends, J.B.A.; Verstraete, W. 100 years of microbial electricity production: Three concepts for the future. Microb. Biotechnol. 2012, 5, 333–346.

- Lovley, D.R. Microbial fuel cells: Novel microbial physiologies and engineering approaches. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2006, 17, 327–332.

- Lovley, D.R. Cleaning up with genomics: Applying molecular biology to bioremediation. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2003, 1, 35–44.

- Ing, N.L.; El-Naggar, M.Y.; Hochbaum, A.I. Going the distance: Long-range conductivity in protein and peptide bioelectronic materials. J. Phys. Chem. B 2018, 122, 10403–10423.

- Lovley, D.R. e-Biologics: Fabrication of sustainable electronics with “green” biological materials. mBio 2017, 8, e00695-17.

- Smith, A.F.; Liu, X.; Woodard, T.L.; Fu, T.; Emrick, T.; Jiménez, J.M.; Lovley, D.R.; Yao, J. Bioelectronic protein nanowire sensors for ammonia detection. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 1479–1484.

- Lin, W.C.; Coppi, M.V.; Lovley, D.R. Geobacter sulfurreducens can grow with oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2525–2528.

- Lovley, D.R. Dissimilatory metal reduction. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1993, 47, 263–290.

- Williams, K.H.; Bargar, J.R.; Lloyd, J.R.; Lovley, D.R. Bioremediation of uranium-contaminated groundwater: A systems approach to subsurface biogeochemistry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2013, 24, 489–497.

- Bowman, S.E.; Bren, K.L. The chemistry and biochemistry of heme c: Functional bases for covalent attachment. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2008, 25, 1118–1130.

- Moore, G.R.; Pettigrew, G.W. Cytochromes c: Evolutionary, structural and physicochemical aspects. In Molecular Biology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990.

- Pokkuluri, P.R.; Londer, Y.Y.; Wood, S.J.; Duke, N.E.; Morgado, L.; Salgueiro, C.A.; Schiffer, M. Outer membrane cytochrome c, OmcF, from Geobacter sulfurreducens: High structural similarity to an algal cytochrome c6. Proteins 2009, 74, 266–270.

- Morgado, L.; Bruix, M.; Pokkuluri, P.R.; Salgueiro, C.A.; Turner, D.L. Redox- and pH-linked conformational changes in triheme cytochrome PpcA from Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochem. J. 2017, 474, 231–246.

- Pokkuluri, P.R.; Londer, Y.Y.; Duke, N.E.; Pessanha, M.; Yang, X.; Orshonsky, V.; Orshonsky, L.; Erickson, J.; Zagyansky, Y.; Salgueiro, C.A.; et al. Structure of a novel dodecaheme cytochrome c from Geobacter sulfurreducens reveals an extended 12 nm protein with interacting hemes. J. Struct. Biol. 2011, 174, 223–233.

- Assfalg, M.; Banci, L.; Bertini, I.; Bruschi, M.; Turano, P. 800 MHz 1H NMR solution structure refinement of oxidized cytochrome c7 from Desulfuromonas acetoxidans. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998, 256, 261–270.

- Fernandes, A.P.; Couto, I.; Morgado, L.; Londer, Y.Y.; Salgueiro, C.A. Isotopic labeling of c-type multiheme cytochromes overexpressed in E. coli. Prot. Expr. Purif. 2008, 59, 182–188.

- Messias, A.C.; Kastrau, D.H.; Costa, H.S.; LeGall, J.; Turner, D.L.; Santos, H.; Xavier, A.V. Solution structure of Desulfovibrio vulgaris (Hildenborough) ferrocytochrome c3: Structural basis for functional cooperativity. J. Mol. Biol. 1998, 281, 719–739.

- Morgado, L.; Fernandes, A.P.; Londer, Y.Y.; Bruix, M.; Salgueiro, C.A. One simple step in the identification of the cofactors signals, one giant leap for the solution structure determination of multiheme proteins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 393, 466–470.

- Santos, H.; Turner, D.L.; Xavier, A.V.; le Gall, J. Two-dimensional NMR studies of electron transfer in cytochrome c3. J. Magn. Reson. 1984, 59, 177–180.

- Turner, D.L.; Salgueiro, C.A.; Schenkels, P.; le Gall, J.; Xavier, A.V. Carbon-13 NMR studies of the influence of axial ligand orientation on haem electronic structure. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1995, 1246, 24–28.

- Lloyd, J.R.; Leang, C.; Myerson, A.L.H.; Coppi, M.V.; Cuifo, S.; Methe, B.; Sandler, S.J.; Lovley, D.R. Biochemical and genetic characterization of PpcA, a periplasmic c-type cytochrome in Geobacter sulfurreducens. Biochem. J. 2003, 369, 153–161.

- Kim, B.C.; Leang, C.; Ding, Y.H.; Glaven, R.H.; Coppi, M.V.; Lovley, D.R. OmcF, a putative c-type monoheme outer membrane cytochrome required for the expression of other outer membrane cytochromes in Geobacter sulfurreducens. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4505–4513.

- Ueki, T.; DiDonato, L.N.; Lovley, D.R. Toward establishing minimum requirements for extracellular electron transfer in Geobacter sulfurreducens. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2017, 364, fnx093.

- Yi, H.; Nevin, K.P.; Kim, B.-C.; Franks, A.E.; Klimes, A.; Tender, L.M.; Lovley, D.R. Selection of a variant of Geobacter sulfurreducens with enhanced capacity for current production in microbial fuel cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2009, 24, 3498–3503.

- Jensen, H.M.; Albers, A.E.; Malley, K.R.; Londer, Y.Y.; Cohen, B.E.; Helms, B.A.; Weigele, P.; Groves, J.T.; Ajo-Franklin, C.M. Engineering of a synthetic electron conduit in living cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 19213.