Currently, the global agricultural system is focused on a limited number of crop species, thereby presenting a threat to food security and supply, especially with predicted global climate change conditions. The importance of ‘underutilized’ crop species in meeting the world’s demand for food has been duly recognized by research communities, governments and policy makers worldwide. The development of underutilized crops, with their vast genetic resources and beneficial traits, may be a useful step towards solving food security challenges by offering a multifaceted agricultural system that includes additional important food resources. Bambara groundnut is among the beneficial underutilized crop species that may have a positive impact on global food security through organized and well-coordinated multidimensional breeding programs. The excessive degrees of allelic difference in Bambara groundnut germplasm could be exploited in breeding activities to develop new varieties. It is important to match recognized breeding objectives with documented diversity in order to significantly improve breeding.

- bambara groundnut

- climate change

- crop improvement

- food security

- underutilized species

1. Introduction

2. Genetic Diversity in Bambara Groundnut

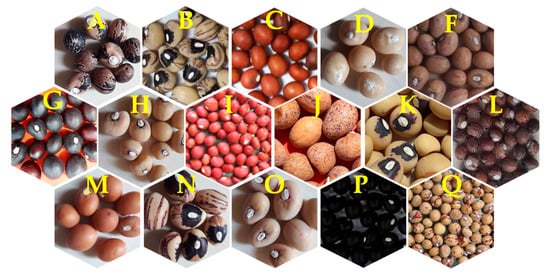

The assessment of available genetic diversity is fundamental in the improvement of Bambara groundnut, which is mostly restricted to small scale traditional farming systems in which they have been commonly cultivated from the existing landraces [45][33]. Landraces are more phenotypically and genotypically diverse compared to pure lines and are excellent sources of genetic variation for breeding [46][34]. Cultivated landraces were developed from the wild progenitor (Vigna subterranea var. spontanea) [47][35]. Bambara groundnut is grown from landraces in all the major growing regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, and its yield can be unstable and unpredictable across different geographical regions. While being adapted to their current environment, landraces may not contain the optimal combination of traits [44][36]. Globally, up to 6145 Bambara groundnut landraces/accessions are conserved ex-situ and these collections are kept in trust by international or regional gene banks, which are comprised of several countries (Table 1). Genetic variability, which could be beneficial for the improvement of the genetic performance of any crop species [48][37], is largely preserved in the form of landraces [48][37]. A significant quantity of genetic diversity has been maintained in the landraces of Bambara groundnut under low input systems of farming [47][35]. Traditional farmers of Bambara groundnut depend on the prevailing diversity among the cultivated landraces and this has enhanced the maintenance of on-farm genetic diversity in its conservation [49][38]. Ex-situ conservation of Bambara groundnut landraces is necessary for the crop’s future genetic improvement programs. However, landraces are problematic when it comes to understanding the genetic background of traits of interest for crop improvement because they are a mixture of numerous genotypes (Figure 2), which may bring about confusion between genotypic and environmental effects [50][39]. These genetic resources are the basis for present and future food security [51][40]. Genetic diversity within lines and populations is central to breeding and germplasm conservation programs [52][41]. As such, it is pertinent to know the genetic diversity among breeding materials to avoid the risks related to increased uniformity in elite germplasm, and to ensure long-term selection gain as a cross between the limited number of elite lines that put them at risk of losing their genetic diversity [53][42].

| S/N | Country | Inst. Code | Nature of Research | Acronym | Accessions Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| References | Accessions No. | % | WT | LR | BL | AC | OT | ||||

| 1 | Nigeria | 039 | IITA | 2031 | 33 | <1 | 100 | - | - | - | |

| 2 | France | 202 | ORSTMONTP | 1416 | 23 | - | 100 | - | - | - | |

| S/N | Trait Descriptor | Scale (Measure) | References | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea | Habit of growth | ) | Spreading Branch Semi-branch |

Sing Sequence Repeat (SSR)[28] [36][ |

SSR-based analysis of genetic diversity of Ghanaian Bambara groundnut landraces67] [60][49] [63][ |

[7952] [][76]71][68] |

||||||||||

| 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Sing Sequence Repeat and Diversity Array Technology (SSR, DArT) | Fully expanded terminal leaflet color | Green | SSR-based analysis of genetic diversity and population structure in Bambara groundnut landraces Purple Red |

[62][51] [66][56] |

3 | Botswana | 002 | DAR | 338 | 6 | - | 2 | - | - | 98 | |

| [ | 76 | ][68] | 3 | The shape of the terminal leaflet | Elliptic Lanceolate Round Oval |

[77][69] [77][69] [34][63] [78][ | ||||||||||

| Sing Sequence Repeat and Diversity Array Technology (SSR, DArT) | Construction of linkage map and QTL analysis of phenotypic traits in Bambara groundnut | 70 | ] | [95][87] | 4 | Ghana | 091 | PGRRI | 296 | |||||||

| 4 | Pigmentation on the petiole | |||||||||||||||

| Directed Amplification of Minisatellite and Start codon targeted (DAMD, SCoT) | Pinkish green | Green |

Competency assessment of directed amplified minisatellite DNA and start codon targeted markers for genetic diversity study in Bambara groundnut | [103][95[79][71] [ | 5 | - | - | - | - | 100 | ||||||

| 80 | ] | [ | 72] | ] | 5 | Tanzania | 016 | NPGRC | 283 | 5 | <1 | 81 | - | - | 18 | |

| 5 | ||||||||||||||||

| Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) | Color of pod | Purple Black Brown Yellowish-brown |

[ | Assessment of genetic relationships based on the morphological characters and RAPD markers in Bambara groundnut | [104][96]79] | 6 | Zambia | 030 | NPGRC | 232 | 4 | - | 100 | - | - | - |

| 7 | Others | (26) | Others (26) | 1549 | 25 | 1 | 59 | 9 | 1 | 29 | ||||||

| TOTAL | 6145 | 100 | <1 | 79 | 2 | <1 | 18 | |||||||||

| [ | |||

| 71 | |||

| ] | |||

| [ | |||

| 65 | ] | [ | 55] |

| 6 | Pod texture | Smooth Rough Many grooves Little groove Folded |

[31] [63][52] [77][69] [30] |

| 7 | Pod shape | Book pointed end on the other side Round pointed end on the other side No point at all sides |

[63][52] [77][69] |

| 8 | Shape of seed | Oval Round |

[64][54] [34][63] |

| Crop Type | Types of Markers | |

|---|---|---|

| Sing Sequence Repeat (SSR) | ||

| Microsatellite-based marker molecular analysis of Ghanaian Bambara groundnut landraces alongside morphological characterization | ||

| [ | 76 | ][68] |

| Diversity Array Technology (DArT) | DArT-based marker genetic diversity analysis in Bambara groundnut, as revealed by phenotypic descriptors | [45][33] |

| Random Amplification of Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) | Genetic diversity in Bambara groundnut landraces assessed by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA RAPD markers | [105][97] |

References

- Godfray, H.C.J.; Garnett, T. Food security and sustainable intensification food security and sustainable intensification. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2014, 369, 6–11.

- Takahashi, Y.; Somta, P.; Muto, C.; Iseki, K.; Naito, K.; Pandiyan, M.; Natesan, S.; Tomooka, N. Novel genetic resources in the genus vigna unveiled from gene bank accessions. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147568.

- Khan, F.; Chai, H.H.; Ajmera, I.; Hodgman, C.; Mayes, S.; Lu, C. A Transcriptomic comparison of two bambara groundnut landraces under dehydration stress. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8, 121.

- Mayes, S.; Massawe, F.J.; Alderson, P.G.; Roberts, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Hermann, M. The potential for underutilized crops to improve security of food production. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 1075–1079.

- Chanyalew, S.; Ferede, S.; Damte, T.; Fikre, T.; Genet, Y.; Kebede, W. Significance and prospects of an orphan crop tef. Planta 2019.

- Ho, W.K.; Chai, H.H.; Kendabie, P.; Ahmad, N.S.; Jani, J.; Massawe, F.; Kilian, A.; Mayes, S. Integrating genetic maps in bambara groundnut [Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.] and their syntenic relationships among closely related legumes. BMC Genom. 2017, 18, 1–9.

- Glenn, K.C.; Alsop, B.; Bell, E.; Goley, M.; Jenkinson, J.; Liu, B.; Martin, C.; Parrott, W.; Souder, C.; Sparks, O.; et al. Bringing new plant varieties to market: Plant breeding and selection practices advance beneficial characteristics while minimizing unintended changes. Crop Sci. 2017, 57, 2906–2921.

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Grace, V.; Chimonyo, P.; Hlahla, S.; Massawe, F. Prospects of orphan crops in climate change. Planta 2019, 250, 695–708.

- Gruber, K. The Living Library. Nature 2017, 544, S8–S10.

- AOCC. The African Orphan Crops Consortium. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- EconomistEconomist. No crop left behind: Improving the plants that Africans eat and breeders neglect. Economist 2017. Available online: (accessed on 5 December 2018).

- UN. United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Available online: (accessed on 15 January 2019).

- Hendre, P.S.; Muthemba, S.; Kariba, R.; Muchugi, A.; Fu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Song, B.; Liu, H.; Liu, M.; Liao, X.; et al. African Orphan Crops Consortium (AOCC): Status of Developing Genomic Resources for African Orphan Crops. Planta 2019, 250, 989–1003.

- LATINCROP. An Integrated Strategy for the Conservation and Use of Underutilized Latin American Agrobiodiversity. 2019. Available online: (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Dawson, I.K.; Powell, W.; Hendre, P.; Ban, J.; Hickey, J.M.; Kindt, R.; Hoad, S.; Hale, I. Tansley review the role of genetics in mainstreaming the production of new and orphan crops to diversify food systems and support human nutrition. New Phytol. 2019, 224, 37–54.

- Tadele, Z.; Bartels, D. Promoting orphan crops research and development. Planta 2019, 250, 675–676.

- Kahane, R.; Hodgkin, T.; Jaenicke, H.; Hoogendoorn, C.; Hermann, M.; Dyno Keatinge, J.D.H.; D’Arros Hughes, J.; Padulosi, S.; Looney, N. Agrobiodiversity for food security, health and income. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 33, 671–693.

- Barbieri, R.L.; Gomes, J.C.C.; Alercia, A.; Padulosi, S. Agricultural biodiversity in Southern Brazil: Integrating efforts for conservation and use of neglected and underutilized species. Sustainability 2014, 6, 741–757.

- Ndidi, U.S.; Ndidi, C.U.; Aimola, I.A.; Bassa, O.Y.; Mankilik, M.; Adamu, Z. Effects of processing (boiling and roasting) on the nutritional and antinutritional properties of bambara groundnuts (Vigna subterranea [L.] Verdc.) from Southern Kaduna. Nigeria 2014, 2014, 472129.

- Murevanhema, Y.Y.; Jideani, V.A. Potential of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) milk as a probiotic beverage—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 954–967.

- Oyeyinka, S.A.; Tijani, T.S.; Oyeyinka, A.T.; Arise, A.K.; Balogun, M.A.; Kolawole, F.L.; Obalowu, M.A.; Joseph, J.K. Value added snacks produced from bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) paste or flour. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 88.

- Mazahib, A.M.; Nuha, M.O.; Salawa, I.S.; Babiker, E.E. Some nutritional attributes of bambara groundnut as influenced by domestic processing. Int. Food Res. J. 2013, 20, 1165–1171.

- Bamshaiye, O.M.; Adegbola, J.A.; Bamishaiye, E.I. Bambara groundnut: An under-utilized nut in Africa. Adv. Agric. Biotechnol. 2011, 1, 60–72.

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chibarabada, T.P.; Chimonyo, V.G.P.; Modi, A.T. Modelling climate change impact: A case of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea). Phys. Chem. Earth 2018, 105, 25–31.

- Obidiebube, E.A.; Eruotor, P.G.; Akparobi, S.O.; Okolie, H.; Obasi, C.C. Assessment of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) varieties for adaptation to rainforest agro-ecological zone of anambra state of nigeria. Can. J. Agric. Crop. 2020, 5, 1–6.

- Dalziel, J. Voandzeia Thou. In The Useful Plants of West Tropical Africa; Crown Agents: London, UK, 1937; pp. 269–271.

- Hepper, F.N. The bambara groundnut (Voandzeia subterranea) and kersting’s groundnut (Kerstingiella Geocarpa) wild in West Africa. Kew Bull. 1963, 16, 395–407.

- Goli, A. Characterization and Evaluation of IITA’s Bambara Groundnut Collection. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Conser-Vation and Improvement of Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subtarranea (L.) Verdc.); Begemann, J.H., Mush-Onga, J., Eds.; Internatinal Plant Genetic Resources Institute (IPGRI): Harare, Zimbabwe, 1995.

- Basu, S.; Roberts, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Mayes, S. Bambara Groundnut. Genome mapping and molecular breeding in plants. In Pulses, Sugar and Tuber; Kole, C.M., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 159–173.

- Cheng, A.; Raai, M.N.; Amalina, N.; Zain, M.; Massawe, F.; Singh, A. In search of alternative proteins: Unlocking the potential of underutilized tropical legumes. Food Secur. 2019, 11, 1205–1215.

- Goli, A. Bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.). In Promoting the Con-Servation and Use of Underutilized and Neglected Crops; Heller, J., Begemann, F., Mushonda, J., Eds.; Int. Plant Genet. Resour. Institute: Rome, Italy, 1997; Volume 9, p. 167.

- Olayide, O.E.; Donkoh, S.A.; Gershon, I.; Ansah, K.; Adzawla, W.; Reilly, P.J.O.; Mayes, S.; Feldman, A.; Halimi, R.A.; Nyarko, G.; et al. Handbook of Climate Change Resilience; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Basel, Switzerland, 2018.

- Olukolu, B.A.; Mayes, S.; Stadler, F.; Ng, N.Q.; Fawole, I.; Dominique, D.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Abbott, A.G.; Kole, C. Genetic diversity in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) as revealed by phenotypic descriptors and dart marker analysis. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 347–358.

- Zeven, A.C. Landraces: A review of definitions and classifications. Euphytica 1998, 104, 127–139.

- Massawe, F.J.; Dickinson, M.; Roberts, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N. Genetic diversity in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) landraces revealed by AFLP markers. Genome 2002, 45, 1175–1180.

- Massawe, F.J.; Mwale, S.S.; Roberts, J.A. Breeding in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.): Strategic considerations. Afr. J. Biol. 2005, 4, 463–471.

- Mwale, S.S.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Massawe, F.J. Growth and development of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) in response to soil moisture 1. dry matter and yield. Eur. J. Agron. 2007, 26, 345–353.

- Mubaiwa, J.; Fogliano, V.; Chidewe, C.; Bakker, E.J.; Linnemann, A.R. Utilization of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) for sustainable food and nutrition security in semi-arid regions of zimbabwe. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204817.

- Mayes, S.; Ho, W.K.; Chai, H.H.; Gao, X.; Kundy, A.C.; Mateva, K.I.; Zahrulakmal, M.; Hahiree, M.K.I.M.; Kendabie, P.; Licea, L.C.S.; et al. Bambara groundnut: An exemplar underutilised legume for resilience under climate change. Planta 2019, 250, 803–820.

- Abdullah, N.; Rafii Yusop, M.; Ithnin, M.; Saleh, G.; Latif, M.A. Genetic Variability of Oil Palm Parental Genotypes and Performance of Its’ Progenies as Revealed by Molecular Markers and Quantitative Traits. Comptes Rendus. Biol. 2011, 334, 290–299.

- Ogundele, O.M.; Minnaar, A.; Emmambux, M.N. Effects of micronisation and dehulling of pre-soaked bambara groundnut seeds on microstructure and functionality of the resulting flours. Food Chem. 2017, 214, 655–663.

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Abdullah, N.; Malek, M.A.; Rahim, H.A.; Hussin, G.; Ismail, M.R.; Latif, M.A.; Kareem, I. Genetic Variability and Diversity of Mutant Rice Revealed by Quantitative Traits and Molecular Markers. Agrociencia 2015, 49, 249–266.

- F.A.O. of the United Nations. FAOSTAT Statistics Database; F.A.O. of the United Nations: Roma, Italy, 2017.

- Waziri, P.M.; Massawe, F.J.; Wayah, S.B.; Sani, J.M. Ribosomal DNA variation in landraces of bambara groundnut. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2013, 12, 5395–5403.

- Bonny, B.S.; Seka, D.; Adjoumani, K.; Koffi, K.G.; Kouonon, L.C.; Sie, R.S. Evaluation of the diversity in qualitative traits of bambara groundnut germplasm (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) of Côte d ’Ivoire. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2019, 18, 23–36.

- Hamrick, J.L.; Godt, M.J.W. Allozyme diversity in cultivated crops. Crop Sci. 1997, 37, 26–30.

- Karikari, S.K.; Tabona, T.T. constitutive traits and selective indices of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) verdc) landraces for drought tolerance under Botswana conditions. Phys. Chem. Earth 2004, 29, 1029–1034.

- Ellstrand, N.C.; Elam, D.R. Population genetic consequences of small population size: Implications for plant conservation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1993, 24, 217–242.

- Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Genetic diversity and population structure of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.): Synopsis of the past two decades of analysis and implications for crop improvement programmes. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2016, 63, 925–943.

- Oladosu, Y.; Rafii, M.Y.; Abdullah, N.; Abdul Malek, M.; Rahim, H.A.; Hussin, G.; Abdul Latif, M.; Kareem, I. Genetic Variability and Selection Criteria in Rice Mutant Lines as Revealed by Quantitative Traits. Sci. World J. 2014.

- Bonny, B.S.; Adjoumani, K.; Seka, D.; Koffi, K.G.; Kouonon, L.C.; Koffi, K.K.; Zoro Bi, I.A. Agromorphological divergence among four agro-ecological populations of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) in Côte d’Ivoire. Ann. Agric. Sci. 2019, 64, 103–111.

- Ntundu, W.H.; Shillah, S.A.; Marandu, W.Y.F.; Christiansen, J.L. Morphological diversity of bambara groundnut [Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.] landraces in Tanzania. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2006, 53, 367–378.

- Feldman, A.; Ho, W.K.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Bambara Groundnut is a Climate-Resilient Crop: How Could a Drought-Tolerant and Nutritious Legume Improve Community Resilience in the Face of Climate Change? Springer Nature: Basel, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 151–167.

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Reilly, P.O.; Walker, S.; Mwale, S. Opportunities for underutilised crops in Southern Africa’s post—2015 sustainability opportunities for underutilised crops in Southern Africa’s post—2015 Development Agenda. Sustainability 2016, 8, 302.

- Molosiwa, O.; Basu, S.M.; Stadler, F.; Azam-Ali, S.; Mayes, S. Assessment of genetic variability of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verde.) accessions using morphological traits and molecular markers. Acta Hortic. 2013, 979, 779–790.

- Molosiwa, O.O. Genetic Diversity and Population Structure Analysis of Bambara Groundnuts (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) Landraces Using Morpho-Agronomic Characters and SSR Markers. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK, 2012; pp. 1–285.

- Hoque, A.; Begum, S.; Robin, A.; Hassan, L. Partitioning of rice (Oryza sativa, L.) genotypes based on Morphometric Diversity. Am. J. Exp. Agric. 2015, 7, 242–250.

- Eckert, A.J.; Van Heerwaarden, J.; Wegrzyn, J.L.; Nelson, C.D.; Ross-Ibarra, J.; González-Martínez, S.C.; Neale, D.B. Patterns of population structure and environmental associations to aridity across the range of loblolly pine (Pinus Taeda, L., Pinaceae). Genetics 2010, 185, 969–982.

- Linnemann, A.R.; Craufurd, P.Q. Effects of temperature and photoperiod on phenological development in three genotypes of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea). Ann. Bot. 1994, 74, 675–681.

- Collinson, S.T.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Chavula, K.M.; Hodson, D.A. Growth, develop- ment and yield of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) in Response to Soil Moisture. J. Agric. Sci. 1996, 126, 307–318.

- Brink, M.; Sibuga, K.P.; Tarimo, A.J.P.; Ramolemana, G. Quantifying photothermal influences on reproductive development in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea): Models and Their Vali-Dation. Field. Crop. Res. 2000, 66, 1–14.

- Wu, S.; Ning, F.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, X.; Wang, W. Enhancing omics research of crop responses to drought under field conditions many but limited useful data from omics analysis of. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1–5.

- Gbaguidi, A.A.; Dansi, A.; Dossou-Aminon, I.; Gbemavo, D.S.J.C.; Orobiyi, A.; Sanoussi, F.; Yedomonhan, H. Agromorphological diversity of local bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) collected in benin. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2018, 65, 1159–1171.

- Shego, A.; van Rensburg, W.S.J.; Adebola, P.O. Aassessment of genetic variability in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterrenea L. verdc.) using morphological quantitative traits. Acad. J. Agric. Res. 2013, 1, 45–51.

- Unigwe, A.E.; Gerrano, A.S.; Adebola, P.; Pillay, M. Morphological Variation in Selected Accessions of Bambara Groundnut (Vigna subterranea, L. Verdc.) in South Africa. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 8, 69.

- IPGRI/IITA/BAMNET. Descriptors for bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea); International Plant Genetic Resources Institute: Rome, Italy; International Institute of Tropical Agriculture: Ibadan, Nigeria; The International Bambara Groundnut Network: Bonn, Germany, 2000; ISBN 92-9043-461-9.

- Abu, H.B.; Buah, S.S.J. Characterization of bambara groundnut landraces and their evaluation by farmers in the upper west region of ghana. J. Dev. Sustain. Agric. 2011, 6, 64–74.

- Ntundu, W.H.; Bach, I.C.; Christiansen, J.L.; Andersen, S.B. Analysis of genetic diversity in bambara groundnut [Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.] landraces using amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) Markers. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2004, 3, 220–225.

- Aliyu, S.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. SSR marker development, genetic diversity and population structure analysis of bambara groundnut [Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.] landraces. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2015, 62, 1225–1243.

- Mayes, S.; Ho, W.K.; Kendabie, P.; Chai, H.H.; Aliyu, S.; Feldman, A.; Halimi, R.A.; Massawe, F.; Azam-Ali, S. Applying molecular genetics to underutilised species—Problems and opportunities. Malays. Appl. Biol. 2015, 44, 1–9.

- Aliyu, S.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Beyond Landraces: Developing improved germplasm resources for underutilized species—A case for bambara groundnut. Biotechnol. Genet. Eng. Rev. 2015, 30, 127–141.

- Aliyu, S.; Massawe, F. Microsatellites based marker molecular analysis of ghanaian bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) landraces alongside morphological haracterization. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 777–787.

- Basu, S.; Mayes, S.; Davey, M.; Robert, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Mithen, R.; Pasquet, R.S. Inheritance of domestication traits in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.). Euphytica 2007, 157, 59–68.

- Karikari, S.K. Variability between local and exotic bambara groundnut landraces in Botswana. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2000, 8, 145–152.

- Golestan, F.S.; Rafii, M.Y.; Ismail, M.R.; Mahmud, T.M.M.; Rahim, H.A.; Asfaliza, R.; Malek, M.A.; Latif, M.A. Biochemical, Genetic and Molecular Advances of Fragrance Characteristics in Rice. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2013, 32, 445–457.

- Ghafoor, A.; Sharif, A.; Ahmad, Z.; Zahid, M.A.; Rabbani, M.A. Genetic diversity in blackgram (Vigna mungo, L. Hepper). Field Crop. Res. 2001, 69, 183–190.

- Yuliawati, Y.; Wahyu, Y.; Surahman, M.; Rahayu, A. Genetic variation and agronomic characters of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea, L. Verdc.) lines results of pure line selection from Sukabumi Lanras. J. Agronida 2019, 4, 152–161.

- Malik, M.F.A.; Ashraf, M.; Qureshi, A.S.; Ghafoor, A. Assessment of genetic variability, correlation and path analyses for yield and its components in soybean. Pakistan J. Bot. 2007, 39, 405–413.

- Linnemann, A.R.; Westphal, E.; Wessel, M. Photoperiod regulation of development and growth in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea). Field Crop. Res. 1995, 40, 39–47.

- Brink, M. Rates of progress towards flowering and podding in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) as a function of temperature and photoperiod. Ann. Bot. 1997, 80, 505–513.

- Brink, M. Development, growth and dry matter partitioning in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) as influenced by photo-period and shading. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 1999, 133, 159–166.

- Jorgensen, S.T.; Aubanton, M.; Harmonic, C.; Dieryck, C.; Jacobsen, S.; Simonsen, H.; Ntundu, W.; Stadler, F.; Basu, S.; Christiansen, J. Identification of photoperiod neutral lines of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea) from Tanzania. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Env. Sci. 2009, 6, 20–23.

- Presidor, K.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Developing genetic mapping resources from landrace-derived genotypes that differ for photoperiod sensitivity in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea, L.). Asp. Appl. Biol. 2015, 124, 49–55.

- Choudhary, G.; Ranjitkumar, N.; Surapaneni, M.; Deborah, A.D.; Anuradha, G.; Siddiq, E.A.; Vemireddy, L.R. Molecular genetic diversity of major indian rice cultivars over decadal periods. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e66197.

- Huynh, B.; Close, T.J.; Roberts, P.A.; Hu, Z.; Wanamaker, S.; Lucas, M.R.; Chiulele, R.; Cissé, N.; David, A.; Hearne, S.; et al. Gene pools and the genetic architecture of domesticated cowpea. Plant Genome 2013, 6, 1–8.

- Ahmad, N.; Basu, S.; Redjeki, E.; Murchie, E.; Massawe, F.; Azam-Ali, S.; Kilian, A.; Mayes, S. Developing genetic mapping and marker-assisted techniques in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea, L.) breeding. Acta Hortic. 2013, 979, 437–449.

- Somta, P.; Chankaew, S.; Rungnoi, O.; Srinives, P. Genetic diversity of the bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) as assessed by SSR Markers. Genome 2011, 54, 898–910.

- Ho, W.K.; Muchugi, A.; Muthemba, S.; Kariba, R.; Mavenkeni, B.O.; Hendre, P.; Song, B.; Deynze, A.V.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. Use of microsatellite markers for the assessment of bambara groundnut breeding system and varietal purity before genome sequencing. Genome 2016, 59, 427–431.

- Ahmad, N.S.; Redjeki, E.S.; Ho, W.K.; Aliyu, S.; Mayes, K. Construction of a genetic linkage map and QTL analysis in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.). Genome 2016, 59, 459–472.

- Chai, H.H.; Ho, W.K.; Graham, N.; May, S.; Massawe, F.; Mayes, S. A cross-species gene expression marker-based genetic map and QTL analysis in bambara groundnut. Genes (Basel) 2017, 8, 84.

- Pasquet, R.S.; Schwedes, S.; Gepts, P. Isozyme diversity in bambara groundnut. Crop Sci. 1999, 39, 1228–1236.

- Rungnoi, O.; Suwanprasert, J.; Somta, P.; Srinives, P. Molecular genetic diversity of bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea, L. Verdc.) revealed by RAPD and ISSR marker analysis. SABRAO J. Breed. Genet. 2012, 44, 87–101.

- Massawe, F.J.; Roberts, J.A.; Azam-Ali, S.N.; Davey, M.R. Genetic diversity in bambara groundnut (Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdc.) landraces assessed by Random Amplified Polymorphic DNA (RAPD) markers. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2003, 50, 737–741.

- Abberton, M.; Batley, J.; Bentley, A.; Bryant, J.; Cai, H.; Cockram, J.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Cseke, L.J.; Dempewolf, H.; De Pace, C.; et al. Global agricultural intensification during climate change: A role for genomics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1095–1098.

- Muñoz-Amatriaín, M.; Mirebrahim, H.; Xu, P.; Wanamaker, S.I.; Luo, M.; Alhakami, H.; Alpert, M.; Atokple, I.; Batieno, B.J.; Boukar, O.; et al. Genome resources for climate-resilient cowpea, an essential crop for food security. Plant J. 2017, 89, 1042–1054.

- Hiremath, P.J.; Kumar, A.; Penmetsa, R.V.; Farmer, A.; Schlu, J.A.; Chamarthi, S.K.; Whaley, A.M.; Carrasquilla-garcia, N.; Gaur, P.M.; Up, H.D.; et al. Large-Scale development of cost-effective SNP marker assays for diversity assessment and genetic mapping in chickpea and comparative mapping in legumes. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2012, 10, 716–732.

- Igwe, D.O.; Afiukwa, C.A. Competency assessment of directed amplified minisatellite dna and start codon targeted markers for genetic diversity study in accessions of Vigna subterranea (L.) Verdcourt. J. Crop Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 20, 263–278.