Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Lily Guo and Version 1 by Koralli Panagiota.

The progress in wearable chemosensors is presented with attention drawn to the measuring technologies, their ability to provide robust data, the manufacturing techniques, as well their autonomy and ability to produce power. However, from statistical studies, the issue of patients’ trust in these technologies has arisen. People do not trust their personal data be transferred, stored, and processed through the vastness of the internet, which allows for timely diagnosis and treatment. The issue of power consumption and autonomy of chemosensor-integrated devices is also studied and the most recent solutions to this problem thoroughly presented.

- Wearable Chemosensors

- flexible electronics

- electrochemistry

- biomarkers

- biological fluids

1. Introduction

The term “Chemosensors” was most probably introduced in 1928 by De Castro as mentioned by Butler and Osborne [1], referring to the function of free nerves in biological systems. An explosion, however, has been happening lately since numerous papers on this topic are published every year. Moreover, the tremendous technological revolution in low-priced microelectronics under Android and other open-source operating systems (OS) for micro-devices has opened a new wide field in the market for the so-called “wearables”. Already we possess, or it is very affordable to obtain, wearable smart-microdevices, sometimes incorporating cell–phone features, which also have special sensors installed allowing for our blood pressure, blood glucose, saturated oxygen SpO2, cardiac rhythm, and of course, body temperature [2]. It is needless to mention that whole new pathways have opened into the detection of biochemical substances [3] and indices such as the pH of human sweat [4], or the epidermis [5], as well as the pH values of other body fluids, critical for the health of female organism [6]. Details in the progress made in recent optical, electrochemical, and transistor-based sensors provide an overview of the status of the scientific efforts towards pH sensing, especially as candidate sensors for wearable devices [7]. Optical sensors are especially projected to have a bright future ahead of them due to their intrinsic noninvasive character [8].

It is anticipated that wearable biometric monitoring devices (BMDs) and artificial intelligence (AI) will enable automatic diagnosis and patient biometric data collection and cloud storage in the next decade. Unfortunately, the biomedical community has not yet reached the point where a patient fully trusts a wearable device for diagnosis and health-monitoring. In a recent study performed on adult patients with chronic conditions in France [9], a mere 20% considered that the benefits of wearables technologies (e.g., improving the reactivity in care and reducing the burden of treatment) greatly outweighed the dangers. Only 3% of participants answered that possible negative aspects such as improper use of human intelligence, risks of data server’s hacking, and private patient information misuse greatly outweighed potential benefits. It was established that as much as 35% of the patients would refuse to endorse at least one existing or soon-to-be-available application using BMDs and AI-based tools to benefit their healthcare. Accounting for patients’ perspectives will allow for exploiting BMDs with AI without impairing the human aspects of care, generating a burden or intruding on patients’ lives.

Another interesting issue in wearables is the electrical power, as most of them are supported by one-use or rechargeable batteries. However, studies point out that it is feasible to harvest thermoelectric energy from the human body heat via the Seebeck effect [10]. This methodology seems to be an effective route to develop flexible and miniature thermoelectric generators, enabling an uninterrupted power supply for the wearable devices or corroborating the charging of internal batteries.

This review study aims at presenting the latest progress achieved mainly in the last three years in wearable chemosensors with a focus on healthcare monitoring, due to the intense scientific work invested worldwide, the developments in most sensor types as part of integrated wearable systems will be presented. Evidently, a particular paragraph is dedicated in this work to fully developed wearable sensors or devices. However, one can discover proposals and studies devoted to the concept of “artificial nose”, i.e., sensor systems, providing sensory effects for vapor [11] or aromatic oils [12], and those in the most modern trend of “wearables” [13,14][13][14]. Still, the concepts mentioned above exist as differentiated ones, to a certain extent.

Marching into the second decade of the 21st century, we already have a possible pathway above the biocompatibility of chemosensors in healthcare to follow at least: we must design and produce chemosensor wearables for unified, unique, ubiquitous, and unobtrusive (U4) for customized quantified output as stated by Haghi et al. in 2020 [15].

2. Technical and Science Background

2.1. Model Structure of a Typical Chemosensor

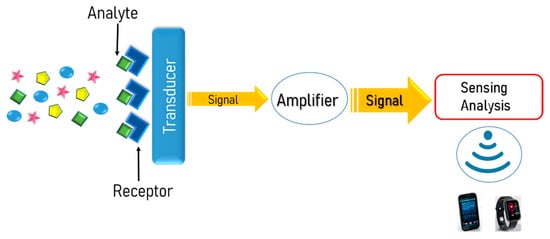

According to the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, a chemosensor is defined as “a device that transforms chemical information, ranging from the concentration of a specific sample component to total composition analysis, into an analytically useful signal” [14]. As shown in Figure 1, a typical chemosensor consists of two main functional units: a receptor that selectively recognizes the analytes of interest with high sensitivity and transforms their concentration into a physical or chemical output signal, and a transducer that alters this output signal to a readable value. Moreover, there is a signal amplifier circuit, a microcontroller, and wireless communication modules for the signal transmission to different displayers, such as a mobile phone or smart watch.

Figure 1.

Schematic illustration of the basic functional units of a typical chemosensor.

Wearable chemosensors can be categorized based on their receptors as affinity or catalytic-based, as well as on sensing principles as electrochemical, capacitive, calorimetric, piezoelectric, optical, and piezoresistive sensors [16,17,18][16][17][18]. Over the past decade, due to the evolving of new technologies, many types of wearable sensors have been rapidly developed since they can provide noninvasive monitoring and real-time information of a wearer’s health status in daily life. Apart from health monitoring, they can be used to improve athlete’s fitness, the optimization of soldier’s performance [18[18][19][20],19,20], and a wide range of purposes like security, communications, and business [19,20,21][19][20][21]. More specifically, wearable electrochemical sensors have received great attention because of their flexibility, portability, and biocompatibility, offering in situ personal health monitoring. Furthermore, the growing interest in those types of wearable sensors stems from the effort of decreasing health care costs transferring the centralized diagnosis and clinical monitoring of a patient at hospitals to personalized care at home [14,16,22,23][14][16][22][23]. Point-of-care-testing exhibit several advantages in patient’s continuous health monitoring, such as convenient application for unskilled users, following of specific biochemical biomarkers, and a significant decrease of testing duration; however, it will never replace laboratory tests.

2.2. Chemosensor Realization Technologies

Generally, wearable chemosensor platforms enabling remote detection and monitoring of analytes comprise three functional elements: (1) the sensing system for physiological signal’s detection and collection, (2) the communication system for data transferring to a remote receptor, and (3) the data analysis system where the collected information from the sensing system will be extracted and evaluated [24]. The great requirement for highly sensitive, portable, and easy-to-use sensing devices that can provide important physiological information forced researchers to develop various detection platforms. Lately, advances in wearable chemosensors have been achieved due to the miniaturization of sensor’s electronics, the progress in material science and engineering, the growth of wireless communication systems, and the advances in energy harvesting systems.

The miniaturization of electronic circuits and devices has contributed significantly to wearable chemosensor’s evolution since one of the major obstacles to further employment of sensing technology into wearable applications was the sensor’s size. Recent advances in the field of microelectronics enable the development of miniature electronic circuits preserving sensing capability, microcontroller operations, and data transmission. Figure 2 illustrates the configuration of a typical example of a sensor employing this technology. The electronic microcircuit system is integrated onto a flexible substrate, detecting the targeted analyte’s signals, and transmitting the corresponding data wirelessly via Bluetooth. Nowadays, miniaturized devices are widely used in many applications, taking advantage of design versatility, high analytical efficacy, and low cost due to the minimization of fabrication materials.

Figure 2.

Bluetooth sensor circuit mounted on a flexible substrate. Source:

(accessed on 20 March 2021).

Another essential component for the construction of wearable chemosensors is the sensing electrodes which are mostly metal-based films. Simultaneously, great efforts have been made for the development of new materials that could be used for the fabrication of wearable biochemical biosensors to ameliorate the sensor’s functionality, such as carbon and polymeric materials, nanocomposites, and nanoparticles [25,26,27][25][26][27]. Furthermore, the flexibility and stretchability of biointegrated electrodes play a key role in developing wearable electronics since it is a crucial design parameter for the uninterrupted operation of the sensor’s microcircuits. The term “electrode’s stretchability” is defined as the electrode’s ability to maintain its conductivity under mechanical deformation and can be quantified as the strain at which the electrode losses its conductivity and being nonconductive [28]. Since it is reported that even a minimum stretch of 1% could provoke a detachment of the electrode from the substrate [29,30][29][30], it is well understood that there is a high demand for high stretchability to preserve the seamless performance of the electrodes in the sensor device. Although there is difficulty finding materials that combine high conductivity and stretchability, composites of stretchable polymers with a conductive metal or carbon are used to obtain the desired properties [28,31][28][31].

Moreover, an emerging area for researchers in the field of chemistry is microfluidics [32,33][32][33]. Recently, microfluidics technology has gained attention because of the reduction in samples and solvent quantities required, resulting in lesser amounts of residue. This technology seems to have great prominence in wearable chemosensor platforms since it can be applied in portable sensor devices of various configurations and composition of the detector [33,34[33][34][35],35], whilst a local anesthetic (dibucaine) was detected with success at arrays of liquid/liquid micro interfaces [36]. Additionally, 2D and 3D printing technologies are used to develop new systems or upgrade existing ones, such as inkjet printing of wireless chemosensors [37]. Herein, further development and combination of the above-mentioned technologies with electrochemical techniques for the fabrication of miniaturized devices could guide a revolution in wearable chemosensors. Moreover, the combination of microfluidics with optics could guide applications for microfluidic drug delivery and drug screening [38], avoiding toxicity effects [39], as well as for tumor-treating [40]

2.3. Micro & Nano-Fabrication Techniques

While many chemosensors are designed in the microscale, in our age nanofabrication techniques are gaining acceptance since materials in the nanoscale demonstrate remarkable properties (physical, chemical, thermoelectrical, mechanical, as well as biological) that makes them attractive candidates for applications in wearable chemosensors offering amended performances. Depending on the sensor’s type, the most suitable nanomaterials, fabrication methods, and transduction principles are selected in order to develop a sensing system with satisfying functionality and compatible wearability. The nanomaterials that will be used to prepare the sensing layer play a key role in selecting the proper fabrication method, whilst several different techniques and processes may be applied for the fabrication of a wearable chemosensor. Researchers use several common fabrication technologies, including printing [41[41][42][43][44],42,43,44], lithography [45[45][46],46], and coating for fabricating sensors in the microscale. As a recent example of micro-fabrication via coating, in their latest paper Koralli et al. [47] presented the fabrication of a p-type CuxO and CuxO:Au compound thin films synthesized by Pulsed Laser Deposition in order to act as a CO gas detector.

Extremely powerful tools of fabrication are also in use for manufacturing sensors in the nanoscale. A direct measurement of electron transport was made possible between DNA molecules by means of carbon nanotube (CNT) as a nanoelectrode. The CNT electrodes were fabricated by focused ion beam bombardment (FIBB) [49]. Similarly, focused ion beam (FIB) systems employ a finely focused beam of ions (typically gallium ions) that, when operated at high beam currents, can be used to locally sputter or mill the sample surface that is exposed to the ion beam [50]. FIB systems have been produced and used commercially for many years, primarily in the semiconductor industry, and thus they have matured and are widely available although with a relative high cost [51].

In general, surface patterning in the micro and nanoscales, has become increasingly important as it enables manufacturing of NEMS-MEMS and sensors allowing for systematic investigation of cell-biomaterial interaction. Additionally, by these technologies it is possible to manufacture rapid, high-throughput tests for disease diagnosis and drug screening [52][48]. Recent advances in three-dimensional patterning allow for recapitulation of the cellular microenvironment, providing valuable insights into the interplay between biomolecules, cells, and biomaterials and facilitating the generation of personalized tissues for regenerative medicine applications [53][49].

It must be here reported, that, the whole armory of almost all types of micro- and nanoenabled chemo/bio sensors was made available to public health systems to detect COVID-19 virus symptoms [54][50] and presence in human breath, fluids etc. [55][51]. Criticism on which sensor–development pathways are best in such pandemics, has also been recently published [56][52].

2.4. 3D Printing

Two-dimensional printing is applying for the preparation of conductive thin films integrated onto inert substrate materials such as ceramics, glass or polymers, as well as for the fabrication of screen-printed electrodes [57[53][54],58], whilst 3D printing facilitates the production of analytical devices and custom labware showing applications in many fields (biomedical engineering, medical science, etc.) [59,60,61][55][56][57]. Moreover, 3D printing is a cost-effective process that exhibits several sustainability benefits, such as materials savings, free design, complex structure’s manufacturing, and extension of the product life [62][58], while due to significant progress in the additive manufacturing process, the fabrication of electronic components and circuits is possible. Several commonly used 3D printing techniques are inkjet printing, fused deposition modelling (FDM), selective laser sintering (SLS), powder bed fusion, stereolithography (SLA), and laminated object manufacturing (LOM), whilst the direct energy deposition (DED) is mostly used for the fabrication of large and less complex components [63][59].

In the past few years, several studies have presented the development of novel 3D-printed microfluidic devices with applications in chemistry and biology [31,64][31][60]. Gowers et al. presented a 3D-printed microfluidic analysis device that acts as a biosensor for the continuous monitoring of glucose and lactate levels in human tissue, comprising an FDA-approved clinical microdialysis probe [65][61]. Under this strategy, Katseli and co-workers designed a ring-shaped wearable sensor device for noninvasive perspiration glucose monitoring, which was fabricated using commercially available filaments and a dual extruder 3D printer through a single–step printing process. The ring sensor was smartphone-addressable enabling self-testing nonenzymatic measurement of glucose levels in sweat [66][62]. A highly innovative glucose sensor was fabricated by printing a photonic microstructure with a periodicity of 1.6 μm, on a glucose-selective hydrogel film functionalized with phenylboronic acid [67][63] for wearable contact lenses. Yeh et al. reported the fabrication of a novel low-cost rotation chip for the real-time determination of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria profile. More specifically, the 3D printed device successfully made a rapid antibiotic-resistant screening test of E. coli by analyzing the RGB color values via a smartphone pixel analysis app [68][64]. Another group presented a portable 3D printed plastic optical fiber sensor compatible with use in IoT sensor applications for respiratory monitoring. The sensor was able to detect and discriminate between normal breathing, deep breathing, and breath-holding through the signal’s amplitude change [69][65]. Gevaerd et al. reported the development of a low-cost, portable, and microfluidic electrochemical sensor device fabricated via 3D printing for the determination of cortisol levels in saliva samples. The lab-made point-of-care sensor device had the ability to detect cortisol in a range of 0.25 to 25.0 μmol/L with exceptional analytical performance [70][66]. In further development of 3D printed biosensing, a new type of flexible piezoresistive tactile sensor was fabricated via a 3D printing method that mimics the texture and sensitivity of human skin. In this design, researchers used a new type of elastomeric 3D printing ink that contains carbon nanotubes distributed on the surfaces of interconnected polydimethylsiloxane microspheres in order to fabricate an electronic skin that simulates touch behavior of human skin, exhibiting high sensitivity, large durability and short time response [71][67].

Three-dimensional printing of a resin-based on the composite between a poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) host matrix and a poly(3,4ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) filler, and the related cumulative volatile organic compounds’ (VOCs) adsorbent properties was recently reported [72][68]. In the context of an interesting approach for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) sensing, an environmentally sustainable route to produce graphene ink designed explicitly for 3D extrusion-printing technology was shown [73][69]. The fabricated sensor devices under this strategy and the new ink displayed high-resolution patterning (average height/thickness of ~12 μm) and a 10-fold improvement in surface area/volume (SA/V) ratio compared to a conventional method of drop-casting.

3. Body Fluids Used for Analysis

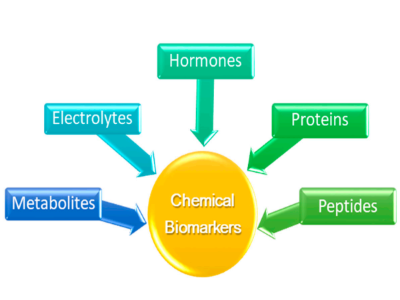

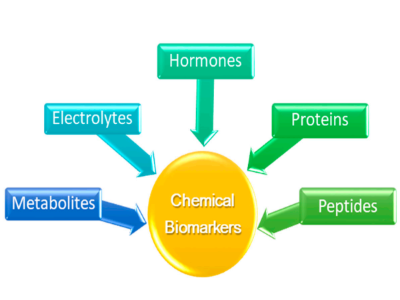

In modern medicine, wearable devices for health care should be characterized by preventive, predictive, personalized, and participatory medicine, according to the 4P medical model [74]. Wearable chemosensors that can be directly worn on the human body can provide meaningful information by perceiving, recording, and real-time analyzing a patient’s pathological and physiological signs with high accuracy. Among the diversified types of biosensors, the electrochemical-based sensing systems are widely used since they demonstrate remarkable advantages such as an easy and low-cost manufacturing process, high sensitivity, quick response, and low energy consumption [75]. Thus far, blood is considered the best diagnostic medium for evaluating human physiology that has been extensively studied; nevertheless, it is unsuitable for continuous monitoring via a wearable device due to the invasive nature of sampling [76]. However, other easily accessible noninvasive body fluids that contain a plethora of physiologically relevant chemical biomarkers (Figure 3) representative of human’s health can be examined by wearable chemosensors such as breath, saliva, tears, sweat, intercellular fluids (ICF), and urine. Among the body fluids mentioned above, saliva, tears, and sweat are biofluids easily obtained, providing continuous access by a wearable device for real-time health status monitoring, whilst sweat is the most approachable sample within a garment structure.

Figure 3. Chemical biomarkers that can be detected via wearable chemosensors

Figure 3. Chemical biomarkers that can be detected via wearable chemosensors

Figure 3. Chemical biomarkers that can be detected via wearable chemosensors

Figure 3. Chemical biomarkers that can be detected via wearable chemosensors 4. Energy Harvesting for Wearables

Power management of wearable sensor devices remains a major challenge for researchers. Different energy harvesting approaches have been developed for wearables energy supply taking into consideration specific requirements of sensor platforms such as size, measurement technique, and sampling frequency. Additional factors regarding wireless communications for data transmission to a display (via Bluetooth, NFC, or passive RFID) also significantly affect energy consumption depending on the operation ranges and bandwidths, as well as location tracking and operation distances.

Catching up from the introductory reference to thermoelectric power generation via the Seebeck effect, some more effects come into play in this area. The thermoelectric effect

is the direct conversion of temperature difference to electric voltage and vice versa via a thermocouple. A thermoelectric device creates a voltage when there is a temperature gradient between the sides of the device.

However, promising thermoelectrics are capable of supplying power by converting body heat, but wearable thermoelectrics have not been as yet, capable of producing electrical power stable or high enough for supporting the uninterrupted operation of commercial types of health monitoring sensors. For this purpose, synergistic integration of a wearable thermoelectric generator (WTEG) and a new type of marketed Li-S battery on the basis of a commercial glucose sensor was proposed [2]. The WTEG has delivered power in a stable and continuous mode, showing a path to overcome one of the biggest hurdles in fully applying thermoelectrics for wearable electronics in practice. As exhibited, the major disadvantage of low thermoelectric output voltage, hampering batteries’ charging, has been greatly alleviated by using the high-performance Li-S battery. The charging voltage of this battery is only half of the standard Li-ion batteries. The WTEG hybrid system was able to continuously produce power as much as 378 µW, operating a commercial glucose sensor (power consumption: 64 µW) and storing the surplus in the Li-S batteries for providing a stable continuous voltage of 2 V even under large fluctuations in power supply and consumption.

Catching up from the introductory reference to thermoelectric power generation via the Seebeck effect, some more effects come into play in this area. The thermoelectric effect

is the direct conversion of temperature difference to electric voltage and vice versa via a thermocouple. A thermoelectric device creates a voltage when there is a temperature gradient between the sides of the device.

However, promising thermoelectrics are capable of supplying power by converting body heat, but wearable thermoelectrics have not been as yet, capable of producing electrical power stable or high enough for supporting the uninterrupted operation of commercial types of health monitoring sensors. For this purpose, synergistic integration of a wearable thermoelectric generator (WTEG) and a new type of marketed Li-S battery on the basis of a commercial glucose sensor was proposed [2]. The WTEG has delivered power in a stable and continuous mode, showing a path to overcome one of the biggest hurdles in fully applying thermoelectrics for wearable electronics in practice. As exhibited, the major disadvantage of low thermoelectric output voltage, hampering batteries’ charging, has been greatly alleviated by using the high-performance Li-S battery. The charging voltage of this battery is only half of the standard Li-ion batteries. The WTEG hybrid system was able to continuously produce power as much as 378 µW, operating a commercial glucose sensor (power consumption: 64 µW) and storing the surplus in the Li-S batteries for providing a stable continuous voltage of 2 V even under large fluctuations in power supply and consumption.

5. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

An effort was undertaken to present the latest progress in the last three years in chemosensors, emphasizing wearables, which is a hot research topic. The authors have tried to incorporate the latest results and proposals for chemosensors for biological fluids in the international literature. In this sense, one can stipulate the idea that the thin border between biosensors and chemosensors is easy to cross. The only criterion is the analyte, possibly in order to be able to distinguish between the two large groups. Certainly, as can be deduced from the works presented in the current study, the wearables are the perfect common ground or integrated application for both these types. It is easy to conclude that significant steps are already taken in making the wearable chemo- and biosensors energy-autonomous. Additionally, their ability to sense more substances is increased. Optical chemosensors are foreseen to have a bright future ahead. Inkjet, screen, and 3D printing procedures will allow for the cheap, easy, and reliable manufacturing of these types of sensors.

Although there has been significant progress in the last few years, there are still significant requirements such as power management, real-time communication, and biocompatibility that have to be addressed for the next generation of wearable chemosensors. The continuous demand for comprising multiple modalities in a sensor platform in combination with wireless communication services and data analytics increases the devices’ power requirements. Several strategies are applied to address the power management challenge, such as the implementation of energy harvesting techniques, the development of supercapacitors, and the fabrication of flexible and light-weight batteries; however, the device’s energy consumption remains one of the major problems facing existing wearable sensors.

Additionally, the real-time, continuous, and uninterrupted transmission of information to a wearer or a computer device is a significant aspect of wearable technology. Up to now, wearable sensor platforms exhibit data transmission capability via Bluetooth, NFC, and high-frequency passive RFID communication protocols. Nevertheless, these communication technologies demonstrate several drawbacks, mainly the compatibility with low-rate data. Researchers should investigate other types of wireless communication technologies that will be used in wearable applications, like optical wireless technologies, as well as develop advanced algorithms for the information’s transmission.

Furthermore, the sensor’s resistance to mechanical damages or the capability to be selfhealing is another issue that must be improved during subsequent years. The employed techniques are not sufficient to protect the sensor device from ordinary wear and tear, unanticipated damage, or unintended stain. Consequently, many efforts have been made for the development of devices that have the ability of self-healing (partially or completely) mimicking natural systems. The advancements in the field of nanomaterials give researchers the opportunity to fabricate such devices in order to improve their reliability and promote durability and lifespan.

Since wearable biosensor devices are highly desired for the real-time determination of a human’s health condition, as well as for elderly care and they are promising in terms of personalized medicine, it is crucial to amend their stability, reliability, safety, and biocompatibility in order to pass from test devices to their commercialization. The nanomaterials’ biocompatibility that comes into direct contact with the epidermis without

causing toxicity effects is essential to be considered in the design and development of wearable biosensors. Various factors such as the size, the shape, and the roughness of the materials placed on the epidermis, as well as their chemistry and degradation, could affect the biocompatibility of the sensor, although it is difficult to predict how exactly a material will behave when interacts with an individual. Regarding this matter, our knowledge, so far, is limited, and there must be further investigation for the development of biocompatible nanomaterials towards safe usage in wearables. According to flexible biosensor platforms, apart from the reliability of the noninvasive sampling of biofluids, another challenge that must be addressed is the interference that provokes several physiological factors, such as temperature, as well as the adhesion of the sensor to the epidermis. Additionally, the sampling frequency is one more factor that has to be investigated in detail since there must be a balance taking into consideration, on the one hand, the sampling rate and on the other hand, the energy consumption of the device. Hence, there must be an optimization between power management and sampling frequency. Additionally, a major issue arose from population research because the common person or patients still do not place their trust in these sensors for medical monitoring and timely treatment. Handling and security of (their) big data and personalized information is a significant issue that should be considered and confronted as early as possible.

However, we are optimistic about the high potential of wearable chemosensors technologies along with the advances in the Industry 4.0, IoT and all advances to come it can be foreseen that the lifestyle and quality of life and health shall improve in the coming years. Our speed to counteract pandemics and detect pathogens will improve and likewise personalized medicine and being alert to dangerous conditions of our health will considerably increase our abilities to the protection of human life.

Although there has been significant progress in the last few years, there are still significant requirements such as power management, real-time communication, and biocompatibility that have to be addressed for the next generation of wearable chemosensors. The continuous demand for comprising multiple modalities in a sensor platform in combination with wireless communication services and data analytics increases the devices’ power requirements. Several strategies are applied to address the power management challenge, such as the implementation of energy harvesting techniques, the development of supercapacitors, and the fabrication of flexible and light-weight batteries; however, the device’s energy consumption remains one of the major problems facing existing wearable sensors.

Additionally, the real-time, continuous, and uninterrupted transmission of information to a wearer or a computer device is a significant aspect of wearable technology. Up to now, wearable sensor platforms exhibit data transmission capability via Bluetooth, NFC, and high-frequency passive RFID communication protocols. Nevertheless, these communication technologies demonstrate several drawbacks, mainly the compatibility with low-rate data. Researchers should investigate other types of wireless communication technologies that will be used in wearable applications, like optical wireless technologies, as well as develop advanced algorithms for the information’s transmission.

Furthermore, the sensor’s resistance to mechanical damages or the capability to be selfhealing is another issue that must be improved during subsequent years. The employed techniques are not sufficient to protect the sensor device from ordinary wear and tear, unanticipated damage, or unintended stain. Consequently, many efforts have been made for the development of devices that have the ability of self-healing (partially or completely) mimicking natural systems. The advancements in the field of nanomaterials give researchers the opportunity to fabricate such devices in order to improve their reliability and promote durability and lifespan.

Since wearable biosensor devices are highly desired for the real-time determination of a human’s health condition, as well as for elderly care and they are promising in terms of personalized medicine, it is crucial to amend their stability, reliability, safety, and biocompatibility in order to pass from test devices to their commercialization. The nanomaterials’ biocompatibility that comes into direct contact with the epidermis without

causing toxicity effects is essential to be considered in the design and development of wearable biosensors. Various factors such as the size, the shape, and the roughness of the materials placed on the epidermis, as well as their chemistry and degradation, could affect the biocompatibility of the sensor, although it is difficult to predict how exactly a material will behave when interacts with an individual. Regarding this matter, our knowledge, so far, is limited, and there must be further investigation for the development of biocompatible nanomaterials towards safe usage in wearables. According to flexible biosensor platforms, apart from the reliability of the noninvasive sampling of biofluids, another challenge that must be addressed is the interference that provokes several physiological factors, such as temperature, as well as the adhesion of the sensor to the epidermis. Additionally, the sampling frequency is one more factor that has to be investigated in detail since there must be a balance taking into consideration, on the one hand, the sampling rate and on the other hand, the energy consumption of the device. Hence, there must be an optimization between power management and sampling frequency. Additionally, a major issue arose from population research because the common person or patients still do not place their trust in these sensors for medical monitoring and timely treatment. Handling and security of (their) big data and personalized information is a significant issue that should be considered and confronted as early as possible.

However, we are optimistic about the high potential of wearable chemosensors technologies along with the advances in the Industry 4.0, IoT and all advances to come it can be foreseen that the lifestyle and quality of life and health shall improve in the coming years. Our speed to counteract pandemics and detect pathogens will improve and likewise personalized medicine and being alert to dangerous conditions of our health will considerably increase our abilities to the protection of human life.

References

- Butler, P.J.; Osborne, M.P. The effect of cervical vagotomy (decentralization) on the ultrastructure of the carotid body of the duck, Anas platyrhynchos. Cell Tissue Res. 1975, 163, 491–502.

- Kim, J.; Khan, S.; Wu, P.; Park, S.; Park, H.; Yu, C.; Kim, W. Self-charging wearables for continuous health monitoring. Nano Energy 2021, 79, 105419.

- Li, Q.; Xia, Y.; Wan, X.; Yang, S.; Cai, Z.; Ye, Y.; Li, G. Morphology-dependent MnO2/nitrogen-doped graphene nanocomposites for simultaneous detection of trace dopamine and uric acid. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 109, 110615.

- Scarpa, E.; Mastronardi, V.M.; Guido, F.; Algieri, L.; Qualtieri, A.; Fiammengo, R.; Rizzi, F.; De Vittorio, M. Wearable piezoelectric mass sensor based on pH sensitive hydrogels for sweat pH monitoring. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–10.

- Bandodkar, A.J.; Hung, V.W.S.; Jia, W.; Valdés-Ramírez, G.; Windmiller, J.R.; Martinez, A.G.; Ramírez, J.; Chan, G.; Kerman, K.; Wang, J. Tattoo-based potentiometric ion-selective sensors for epidermal pH monitoring. Analyst 2013, 138, 123–128.

- Pal, A.; Nadiger, V.G.; Goswami, D.; Martinez, R.V. Conformal, waterproof electronic decals for wireless monitoring of sweat and vaginal pH at the point-of-care. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 160, 112206.

- Vivaldi, F.; Salvo, P.; Poma, N.; Bonini, A.; Biagini, D.; Del Noce, L.; Melai, B.; Lisi, F.; Di Francesco, F. Recent Advances in Optical, Electrochemical and Field Effect pH Sensors. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 33.

- Giannetti, A.; Bocková, M. Optical chemosensors and biosensors. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 33.

- Tran, V.-T.; Riveros, C.; Ravaud, P. Patients’ views of wearable devices and AI in healthcare: Findings from the ComPaRe e-cohort. NPJ Digit. Med. 2019, 2, 1–8.

- Liu, E.; Negm, A.; Howlader, M.M.R. Thermoelectric generation via tellurene for wearable applications: Recent advances, research challenges, and future perspectives. Mater. Today Energy 2021, 20, 100625.

- Zhang, M.; Shi, J.; Liao, C.; Tian, Q.; Wang, C.; Chen, S.; Zang, L. Perylene imide-based optical chemosensors for vapor detection. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 1.

- Okur, S.; Sarheed, M.; Huber, R.; Zhang, Z.; Heinke, L.; Kanbar, A.; Wöll, C.; Nick, P.; Lemmer, U. Identification of Mint Scents Using a QCM Based E-Nose. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 31.

- Kim, J.; Campbell, A.S.; de Ávila, B.E.F.; Wang, J. Wearable biosensors for healthcare monitoring. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 389–406.

- Bandodkar, A.J.; Wang, J. Non-invasive wearable electrochemical sensors: A review. Trends Biotechnol. 2014, 32, 363–371.

- Haghi, M.; Deserno, T.M. General conceptual framework of futurewearables in healthcare: Unified, unique, ubiquitous, and unobtrusive (U4) for customized quantified output. Chemosensors 2020, 8, 85.

- Qian, R.C.; Long, Y.T. Wearable Chemosensors: A Review of Recent Progress. Chem. Open 2018, 7, 118–130.

- Castano, L.M.; Flatau, A.B. Smart fabric sensors and e-textile technologies: A review. Smart Mater. Struct. 2014, 23.

- Toprakci, H.A.K.; Ghosh, T.K. Handbook of Smart Textiles. Handb. Smart Text. 2014, 1–19.

- Li, Z.; Ge, Z.; Tong, X.; Guo, L.; Huo, J.; Li, D.; Li, H.; Lu, A.; Li, T. Phosphorescent iridium(III) complexes bearing L-alanine ligands: Synthesis, crystal structures, photophysical properties, DFT calculations, and use as chemosensors for Cu2+ ion. Dye Pigment. 2021, 186, 109016.

- Awolusi, I.; Marks, E.; Hallowell, M. Wearable technology for personalized construction safety monitoring and trending: Review of applicable devices. Autom. Constr. 2018, 85, 96–106.

- Lim, S.; Son, D.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.B.; Song, J.K.; Choi, S.; Lee, D.J.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, M.; Hyeon, T.; et al. Transparent and stretchable interactive human machine interface based on patterned graphene heterostructures. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2015, 25, 375–383.

- Brown, M.S.; Ashley, B.; Koh, A. Wearable technology for chronic wound monitoring: Current dressings, advancements, and future prospects. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2018, 6, 1–21.

- Bocchetta, P.; Frattini, D.; Ghosh, S.; Mohan, A.M.V.; Kumar, Y.; Kwon, Y. Soft materials for wearable/flexible electrochemical energy conversion, storage, and biosensor devices. Materials 2020, 13, 2733.

- Patel, S.; Park, H.; Bonato, P.; Chan, L.; Rodgers, M. A review of wearable sensors and systems with application in rehabilitation. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2012, 21, 1–17.

- Xiong, J.; Cui, P.; Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Parida, K.; Lin, M.-F.; Lee, P.S. Skin-touch-actuated textile-based triboelectric nanogenerator with black phosphorus for durable biomechanical energy harvesting. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 4280.

- Li, G.; Mo, X.; Law, W.-C.; Chan, K.C. Wearable fluid capture devices for electrochemical sensing of sweat. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 11, 238–243.

- Kabiri Ameri, S.; Ho, R.; Jang, H.; Tao, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Schnyer, D.M.; Akinwande, D.; Lu, N. Graphene electronic tattoo sensors. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 7634–7641.

- Chen, X. Making Electrodes Stretchable. Small Methods 2017, 1, 1600029.

- Fattahi, P.; Yang, G.; Kim, G.; Abidian, M.R. A review of organic and inorganic biomaterials for neural interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 1846–1885.

- Qi, D.; Liu, Z.; Yu, M.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Lv, J.; Li, Y.; Wei, J.; Liedberg, B.; Yu, Z.; et al. Highly stretchable gold nanobelts with sinusoidal structures for recording electrocorticograms. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 3145–3151.

- He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Fu, J.Z.; Gao, Q.; Qiu, J.J. Developments of 3D Printing Microfluidics and Applications in Chemistry and Biology: A Review. Electroanalysis 2016, 28, 1658–1678.

- Li, S.; Ma, Z.; Cao, Z.; Pan, L.; Shi, Y. Advanced Wearable Microfluidic Sensors for Healthcare Monitoring. Small 2020, 16, 1–15.

- Mejía-Salazar, J.R.; Cruz, K.R.; Vásques, E.M.M.; de Oliveira, O.N. Microfluidic point-of-care devices: New trends and future prospects for ehealth diagnostics. Sensors 2020, 20, 1951.

- Agustini, D.; Fedalto, L.; Agustini, D.; de Matos dos Santos, L.G.; Banks, C.E.; Bergamini, M.F.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H. A low cost, versatile and chromatographic device for microfluidic amperometric analyses. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 304, 127117.

- Martín, A.; Kim, J.; Kurniawan, J.F.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Moreto, J.R.; Tang, G.; Campbell, A.S.; Shin, A.; Lee, M.Y.; Liu, X.; et al. Epidermal Microfluidic Electrochemical Detection System: Enhanced Sweat Sampling and Metabolite Detection. ACS Sens. 2017, 2, 1860–1868.

- Almbrok, E.M.; Yusof, N.A.; Abdullah, J.; Mohd Zawawi, R. Electrochemical Detection of a Local Anesthetic Dibucaine at Arrays of Liquid|LiquidMicroInterfaces. Chemosensors 2021, 9, 15.

- Hartwig, M.; Zichner, R.; Joseph, Y. Inkjet-printed wireless chemiresistive sensors-A review. Chemosensors 2018, 6, 66.

- Teymourian, H.; Parrilla, M.; Sempionatto, J.; Montiel, N.F.; Barfidokht, A.; Van Echelpoel, R.; De Wael, K.; Wang, J. Wearable Electrochemical Sensors for the Monitoring and Screening of Drugs. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2679–2700.

- Damiati, S.; Kompella, U.B.; Damiati, S.A.; Kodzius, R. Microfluidic devices for drug delivery systems and drug screening. Genes 2018, 9, 103.

- Pavesi, A.; Adriani, G.; Tay, A.; Warkiani, M.E.; Yeap, W.H.; Wong, S.C.; Kamm, R.D. Engineering a 3D microfluidic culture platform for tumor-treating field application. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 1–10.

- Su, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, B.; Yang, T.; Yang, B.; Xie, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Tai, H.; Cai, Z.; et al. Alveolus-Inspired Active Membrane Sensors for Self-Powered Wearable Chemical Sensing and Breath Analysis. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 6067–6075.

- Jiang, Y.; Shen, L.; Ma, J.; Ma, H.; Su, Y.; Zhu, N. Wearable Porous Au Smartsensors for On-Site Detection of Multiple Metal Ions. Anal. Chem. 2021.

- Zheng, Y.; He, Z.Z.; Yang, J.; Liu, J. Personal electronics printing via tapping mode composite liquid metal ink delivery and adhesion mechanism. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 1–8.

- Jiang, X.; Zhang, R.; Yang, T.; Lin, S.; Chen, Q.; Zhen, Z.; Xie, D.; Zhu, H. Foldable and electrically stable graphene film resistors prepared by vacuum filtration for flexible electronics. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2016, 299, 22–28.

- Tian, L.; Li, Y.; Webb, R.C.; Krishnan, S.; Bian, Z.; Song, J.; Ning, X.; Crawford, K.; Kurniawan, J.; Bonifas, A.; et al. Flexible and Stretchable 3ω Sensors for Thermal Characterization of Human Skin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1–9.

- Xu, B.; Akhtar, A.; Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Yeo, W.H.; Park, S.; Boyce, B.; Kim, H.; Yu, J.; Lai, H.Y.; et al. An Epidermal Stimulation and Sensing Platform for Sensorimotor Prosthetic Control, Management of Lower Back Exertion, and Electrical Muscle Activation. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4462–4471.

- Koralli, P.; Petropoulou, G.; Mouzakis, D.E.; Mousdis, G.K.M. Efficient CO sensing by a CuO: Au nanocomposite thin film deposited by PLD on a Pyrex tube. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2021. submitted for publication.

- Sasaki, T.K.; Ikegami, A.; Mochizuki, M.; Aoki, N.; Ochiai, Y. Transport measurements of DNA molecules by using carbon nanotube nano-electrodes. AIP Conf. Proc. 2005, 772, 1091–1092.

- Wilhelmi, O.; Reyntjens, S.; Van Leer, B.; Anzalone, P.A.; Giannuzzi, L.A. Focused Ion and Electron Beam Techniques; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; ISBN 9780815515944.

- Parmenter, C.D.; Nizamudeen, Z.A. Cryo-FIB-lift-out: Practically impossible to practical reality. J. Microsc. 2021, 281, 157–174.

- Lee, J.S.; Hill, R.T.; Chilkoti, A.; Murphy, W.L. Surface Patterning, 4th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020.

- Liu, N.; Ye, X.; Yao, B.; Zhao, M.; Wu, P.; Liu, G.; Zhuang, D.; Jiang, H.; Chen, X.; He, Y.; et al. Advances in 3D bioprinting technology for cardiac tissue engineering and regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 6, 1388–1401.

- Shan, B.; Broza, Y.Y.; Li, W.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Gui, S.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Multiplexed Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Array for Detection of COVID-19 in Exhaled Breath. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 12125–12132.

- Erdem, Ö.; Derin, E.; Sagdic, K.; Yilmaz, E.G.; Inci, F. Smart materials-integrated sensor technologies for COVID-19 diagnosis. Emerg. Mater. 2021.

- Tong, A.; Sorrell, T.; Black, A.; Caillaud, C.; Chrzanowski, W.; Li, E.; Martinez-Martin, D.; McEwan, A.; Wang, R.; Motion, A.; et al. Research priorities for COVID-19 sensor technology. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 144–147.

- de Araujo Andreotti, I.A.; Orzari, L.O.; Camargo, J.R.; Faria, R.C.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F.; Gatti, A.; Janegitz, B.C. Disposable and flexible electrochemical sensor made by recyclable material and low cost conductive ink. J. Electroanal. Chem. 2019, 840, 109–116.

- Pradela-Filho, L.A.; Araújo, D.A.G.; Takeuchi, R.M.; Santos, A.L. Nail polish and carbon powder: An attractive mixture to prepare paper-based electrodes. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 258, 786–792.

- Manzanares Palenzuela, C.L.; Pumera, M. (Bio)Analytical chemistry enabled by 3D printing: Sensors and biosensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 103, 110–118.

- Zhang, C.; Bills, B.J.; Manicke, N.E. Rapid prototyping using 3D printing in bioanalytical research. Bioanalysis 2017, 9, 329–331.

- Goole, J.; Amighi, K. 3D printing in pharmaceutics: A new tool for designing customized drug delivery systems. Int. J. Pharm. 2016, 499, 376–394.

- Ford, S.; Despeisse, M. Additive manufacturing and sustainability: An exploratory study of the advantages and challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 137, 1573–1587.

- Choudhary, H.; Vaithiyanathan, D.; Kumar, H. A Review on Additive Manufactured Sensors. Mapan J. Metrol. Soc. India 2020.

- Ho, C.M.B.; Ng, S.H.; Li, K.H.H.; Yoon, Y.J. 3D printed microfluidics for biological applications. Lab Chip 2015, 15, 3627–3637.

- Gowers, S.A.N.; Curto, V.F.; Seneci, C.A.; Wang, C.; Anastasova, S.; Vadgama, P.; Yang, G.Z.; Boutelle, M.G. 3D Printed Microfluidic Device with Integrated Biosensors for Online Analysis of Subcutaneous Human Microdialysate. Anal. Chem. 2015, 87, 7763–7770.

- Katseli, V.; Economou, A.; Kokkinos, C. Smartphone-Addressable 3D-Printed Electrochemical Ring for Nonenzymatic Self-Monitoring of Glucose in Human Sweat. Anal. Chem. 2021.

- Elsherif, M.; Hassan, M.U.; Yetisen, A.K.; Butt, H. Wearable Contact Lens Biosensors for Continuous Glucose Monitoring Using Smartphones. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5452–5462.

- Yeh, P.C.; Chen, J.; Karakurt, I.; Lin, L. 3D Printed Bio-Sensing Chip for the Determination of Bacteria Antibiotic-Resistant Profile. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Solid-State Sensors, Actuators and Microsystems and Eurosensors XXXIII (TRANSDUCERS 2019 and EUROSENSORS XXXIII), Berlin, Germany, 23–27 June 2019; IEEE: Berlin, Germany, 2019; pp. 126–129.

- Kam, W.; Mohammed, W.S.; O’Keeffe, S.; Lewis, E. Portable 3-d printed plastic optical fibre motion sensor for monitoring of breathing pattern and respiratory rate. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 5th World Forum Internet Things, WF-IoT, Limerick, Ireland, 15–18 April 2019; pp. 144–148.

- Gevaerd, A.; Watanabe, E.Y.; Belli, C.; Marcolino-Junior, L.H.; Bergamini, M.F. A complete lab-made point of care device for non-immunological electrochemical determination of cortisol levels in salivary samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2021, 332, 129532.

- Wang, H.; Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, L.; Li, J.; Zeng, X. 3D-Printed Flexible Tactile Sensor Mimicking the Texture and Sensitivity of Human Skin. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2019, 4, 1–8.

- Scordo, G.; Bertana, V.; Ballesio, A.; Carcione, R.; Marasso, S.L.; Cocuzza, M.; Pirri, C.F.; Manachino, M.; Gomez, M.G.; Vitale, A.; et al. Effect of volatile organic compounds adsorption on 3D-printed pegda:Pedot for long-term monitoring devices. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 94.

- Hassan, K.; Tung, T.T.; Stanley, N.J.; Yap, P.L.; Farivar, F.; Rastin, H.; Nine, M.J.; Losic, D. Graphene inks for extrusion-based 3D micro printing of chemo-resistive sensing devices for volatile organic compounds (VOCs) detection. Nanoscale 2021.

More