The interaction of the alternative oxidase (AOX) pathway with nutrient metabolism is important for understanding how respiration modulates ATP synthesis and carbon economy in plants under nutrient deficiency. Although AOX activity reduces the energy yield of respiration, this enzymatic activity is upregulated under stress conditions to maintain the functioning of primary metabolism. The in vivo metabolic regulation of AOX activity by phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N) and during plant symbioses with Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF) and Rhizobium bacteria is still not fully understood. We highlight several findings and open questions concerning the in vivo regulation of AOX activity and its impact on plant metabolism during P deficiency and symbiosis with AMF. We also highlight the need for the identification of which metabolic regulatory factors of AOX activity are related to N availability and nitrogen‐fixing legume‐rhizobia symbiosis in order to improve our understanding of N assimilation and biological nitrogen fixation.

- alternative oxidase

- arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi

- nitrogen and phosphorus nutrition

- rhizobium

- plant primary metabolism

1.Regulation Introductionof AOX Activity by P Availability

The main P resource for plants in soils is inorganic phosphate (Pi), which mostly can be retained or complexed by cations (e.g., Ca2+ and Mg2+) [1]. The other P pool in soil comprises organic P compounds derived from the degradation of plant litter, microbial detritus and organic matter [2]. Pi is involved in cellular bioenergetics and metabolic regulation, and it is also important as a structural component of essential biomolecules such as DNA, RNA, phospholipids, ATP and sugar-phosphates [3][4]. A decrease in cytosolic Pi may restrict oxidative phosphorylation, leading to an increased proton gradient and membrane potential. In turn, this prompts an over-reduction of the components of the electron transport chain, inhibiting oxygen consumption through the COX pathway, which is coupled with ATP synthesis. This creates a decrease in the re-oxidation of NADH produced in the TCA cycle [5][6]. Furthermore, the accumulation of NADH in the mitochondrial matrix also inhibits the TCA cycle dehydrogenases, decreasing the activity of the TCA cycle and limiting the production of important metabolic intermediates [7].

A plant trait that enhances the capacity to acquire P in the poorest P soils is the production of cluster roots in members of the Proteaceae family, most of which do not form mycorrhizal associations [8][9][10][11]. Cluster roots are very effective at acquiring P that is largely absorbed into soil particles, because of their pronounced capacity to exude carboxylates [12]. Cluster roots of Lupinus albus release much more citric and malic acid than lupin roots of plants grown under P sufficiency. Florez-Sarasa et al. [13] observed that growth under P limitation increased the activity of AOX in cluster roots of L. albus together with the synthesis of citrate and malate. This is in the line with previous studies describing an incremented AOX abundance in cluster roots of Hakea prostata [14] and in suspension cells of tobacco after exogenous supply of citrate [15]. It is thought that the production of vast amounts of citrate in cluster rootlets is inexorably associated with the production of NADH [13][14][15][16]. This led Florez-Sarasa et al. [13] to state that AOX allows the continuity of TCA cycle activity by re-oxidizing the high levels of NADH produced during citrate synthesis when COX activity is restricted due to the P-deficiency-induced adenylate restriction.

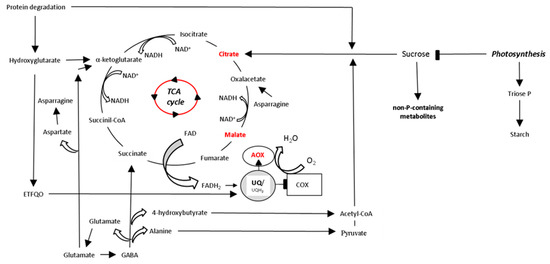

The capacity to synthesize acidifying and/or chelating compounds is not restricted to species with morphological structures such as cluster roots and dauciform roots, although it is less abundant [12]. In roots without these adaptations, and in the absence of mycorrhiza, the levels of enzymes involved in organic acid biosynthesis, such as PEP carboxylase, often increase in response to P starvation in pea, tomato and Brassica nigra [17]. This increase in enzyme levels was related to a higher amount of organic acids being produced for root exudation. This capacity is not only present in roots; leaves of plants grown under P limitation may accumulate carboxylates such as citrate, malate and fumarate [17][18]. Carboxylates in leaves can be transported via the phloem and directed to roots for exudation [17][18]. Pioneering studies reported an adaptive response of respiratory metabolism and the mitochondrial electron transport chain to P limitation in NM roots [19][20][21][22], including increased AOX capacity [20][22][23][24][25]. This in the line with previous studies reporting imbalances of C/N ratio and ROS levels in AOX-deficient cells under P deficiency [22][24], although the situation at tissue level has been recognized to be more complex [26]. Recent studies have observed increases of AOX activity in roots of non-cluster roots for species grown under P limitation, such as Nicotiana tabacum and Solanum lycopersicum in the absence of mycorrhiza [27][28]. In these species, increments of AOX activity were observed, coinciding with a higher synthesis of carboxylates citrate and malate. In leaves, there were reports of pioneer studies reported increases of AOX activity in Phaseolus vulgaris and Gliricidia sepium plants grown under P limitation, but a decrease of foliar AOX activity was observed in Nicotiana tabacum, although this disparity was not related to any respiratory metabolite [29]. A recent study in Solanum lycopersicum plants grown at P-sufficient and limiting conditions, and exposed to sudden short-term (24 h) P-sufficient pulse, observed foliar respiratory bypasses via AOX and an increased accumulation of citrate, together with an enhanced expression of high-affinity P transporters LePT1 and LePT2 in conditions of limited P concentration [28]. These observations suggest that P concentration in plant organs regulates AOX activity in coordination with biochemical and molecular adjustments, functioning as a mechanism directed to maximize P acquisition [28]. Despite these findings, there is still a lack of understanding about the entire metabolic puzzle leading to the synthesis of citrate and increases in AOX activity. Studies combining metabolite profiling and measurements of electron partitioning between COX and AOX in P deficient plants could certainly shed light on the metabolic role of AOX in plant species adapted to P deficiency, which increase carbon use efficiency by decreasing Pi consumption in leaves as represented in Figure 1, below. The rate of photosynthesis and the export of its products from the chloroplast are determined by the availability of Pi in both chloroplast and cytosol [12][30]. Low chloroplast Pi availability induces a decrease in the rate of photosynthesis by decreasing both ATP synthesis and Calvin-Benson cycle activity, which results in a reduced availability of intermediates, e.g., ribulose 1,5-biphosphate (RuBP), and decreased carboxylation activity of Rubisco [31]. Low cytosolic Pi availability decreases the export rate of the products of the Calvin-Benson cycle, leading to increasing amounts of triose-phosphate and starch in the chloroplast [30][31]. Consequently, sucrose formation and glycolysis can be reduced, which may limit carbon supply into mitochondria, thus decreasing both TCA cycle activity and respiration [32][33], and therefore, plant growth and yield. In order to save Pi, leaves reduce Pi consumption in phosphorylation of sugar metabolites by converting phosphorylated metabolites (glucose-6-P, fructose-6-P, inositol-1-P and glycerol-3-P) to non-P-containing di- and tri-saccharides, as observed in Hordeum vulgare and Eucalyptus globulus P-deficient plants [34][35]. In these studies, such changes coincided with reduced levels of organic acid intermediates of the TCA cycle, suggesting a short entry of carbon into mitochondria. Bearing in mind that the conversion of di- and tri-saccharides to organic acids requires Pi, it is unlikely that they can be further respired [34]. Under this circumstance, the use of alternative carbon resources would allow the continuity of TCA cycle reactions to produce organic acids, e.g., citrate for secretion and to sustain the mitochondrial electron transport chain. In this sense, changes in levels of amino acids glutamine, arginine and asparagine was observed in P-deficient plants [34][35]. A similar response was recently observed in Hordeum vulgare [18]. These amino acids were suggested to provide carbon skeletons to mitochondria when plants reduce the consumption of Pi [18]. It is known that plants can metabolize proteins and lipids as alternative respiratory substrates when carbohydrates are scarce in plant cells [36][37][38]. Carbon consumption of these alternative respiratory substrates could be associated with the generation of NADH in the TCA cycle, whose re-oxidation would be favored by AOX activity when COX is restricted under P deficiency (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the TCA cycle and its connection with Pi consumption in leaves of plant species adapted to P deficiency. Low Pi availability limits both photosynthesis and respiration. In chloroplasts, the export rate of the Calvin-Benson cycle products, which are needed for the synthesis of sucrose, decreases under P limitation. This leads to increasing amounts of triose-phosphate and starch in chloroplasts. In cytosol, an accumulation of non-P-containing saccharides allows the cell to save Pi, but it aggravates the short supply of respiratory substrates into mitochondria. In contrast, protein degradation provides carbon skeletons to mitochondria via hydroxyglutarate synthesis that can be used for the synthesis and exudation of rhizosphere carboxylates citrate and malate, and feeds electrons to the mETC through to the ubiquinol pool via an electron-transfer flavoprotein:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETFQO) [36]. Similarly, the γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) shunt allows the entry of carbon skeletons in the form of acetyl-CoA, pyruvate, succinate, oxalacetate and α-ketoglutarate into the TCA cycle from amino acids alanine, glutamate and asparagine [38]. The re-oxidation of NADH generated in the TCA cycle may be favored by AOX activity when COX is restricted by low Pi availability. TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle.

1.1. Regulation of AOX Activity by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis

Regulation of AOX Activity by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis

More than 90% of terrestrial plants are associated with root-colonizing fungi, establishing a durable and close mutualistic symbiosis, called mycorrhiza [39]. The endotrophic arbuscular mycorrhiza is the most common type, occurring in about 80% of plant species [40]. The establishment of the association between AMF and plants implies the generation of roots with representative structures typical of this symbiosis such as (1) intraradical mycelium, which is a fungal structure that inhabits the plant intracellular space; (2) arbuscule, which is the space where the carbon and nutrient exchange between fungus and plant takes place; (3) the vesicles, storage structures; and (4) the extraradical mycelium, which is a structure that extends from the root surface to the soil, beyond the root P-depletion zone and has access to a greater volume of soil compared to roots and root hairs alone [41]. Mycorrhizal associations act as ‘scavengers’ for Pi uptake in the soil solution. Compared to non-mycorrhizal (NM) plants, the advantages of increased P acquisition and photosynthesis increase with decreasing soil P availability [42]. The increase in photosynthesis in plants with mycorrhiza is related to an increased demand for carbohydrates supplied to the fungus [43][44]. Some carbohydrates produced in leaves during photosynthesis are transported to roots, where they are broken down in respiration to produce ATP and carbon skeletons required for protein synthesis. Around 20% of the carbon fixed by photosynthesis is destined to form soluble sugars and organic acids in order to supply energy metabolism in fungal cells [45]. These metabolic carbon requirements of AM symbiosis may affect plant respiration [46][47][48] as well as the levels of primary metabolites in plant organs [49][50][51]. In fact, AM symbiosis decreases the carboxylate-releasing strategy as observed in 10 Kennedia species and five species of legumes [52][53]. The mechanism for the reduction in rhizosphere carboxylates with AM symbiosis could be a consequence of the reduction of carbon availability in roots due to the demand of AMF for carbon compounds, or it could be a consequence of higher plant P concentration due to improved nutrition. Measurements of in vivo AOX activity and the accumulation of carboxylates in roots of Nicotiana tabacum and Arundo donax, showed that AM symbiosis decreased root respiration via COX and AOX in N. tabacum, decreased respiration via COX in A. donax, and decreased synthesis and exudation of citrate and malate in A. donax and N. tabacum, respectively [27][54]. On top of this, both species showed symptoms of ameliorated physiological status and increased biomass accumulation in shoots. These results probably denote that the synthesis of rhizosphere exudates in non-AM plants imposes an important carbon cost detrimental for plant growth as compared with AM plants, which do not invest as much carbon in the synthesis of carboxylates, thus respiring less and allowing carbon to accumulate. Bearing all this in mind, it would be logical to assume that the mechanism for the reduction in rhizosphere carboxylates is related to improved plant P status rather than less carbon availability. In fact, previous studies described that increasing P availability tends to reduce the amount of carboxylate in rhizosphere soil [55][56], and the carboxylate-releasing strategy requires more carbon when P availability is in the range at which AM plants are functional [57]. Nevertheless, it is important to highlight that the effect of AM symbiosis on plant growth is variable because it depends on the host plant and the fungal species [58]. In this sense, in vivo AOX measurements have been made only in positive symbiotic interactions (beneficial for plant growth), and there are still a lack of studies that test the role of alternative respiration in defective symbiotic interactions (detrimental for plant growth). Moreover, it has been reported that the effect of AMF on plant growth depends on the stage of colonization [41]. In this sense, a recent study in N. tabacum showed that symbiosis with Rhizophagus irregularis differently affects both respiration and ATP synthesis in leaves at different growth stages when plants grow in P deficient soils. AM symbiosis represented an ATP cost (via decreased COX activity) for tobacco leaves that was detrimental for shoot growth at early stages, presumably because fungal structures were still under construction. At the mature stage, this cost turned into an ATP benefit (via incremented COX activity), which allowed for faster growth presumably because symbiosis was functional, bearing in mind the observed increase in both foliar P status and shoot growth [59].

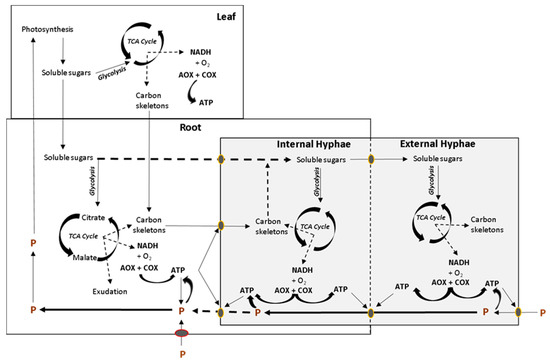

AM symbiosis can improve nutrient acquisition because AM provide an additional means of nutrient uptake, the mycorrhizal nutrient uptake pathway [60][61], which can bypass the pathway of direct nutrient uptake in a P availability-dependent manner [62][63][64][65][66][67]. Studies relating the functioning of the mycorrhizal nutrient uptake pathway to the in vivo electron partitioning to AOX are required, keeping in mind that AOX is also present in various fungi including Rhizophagus intraradices [68], and that P acquisition by AMF requires energy, which is obtained during oxidative phosphorylation in fungal mitochondria. Precisely, ATP is needed for P uptake by the external hyphae, P transport and export to the internal hyphae and P uptake by the plant at the arbuscule (Figure 2). It would be logical to assume that positive AMF-plant interactions display high rates of COX activity in extra radical mycelium to ensure ATP availability and to energize the mycorrhiza pathway uptake. Measurements of the in vivo COX and AOX activities together with techniques such as multicompartment plant growth systems [69] and 13C and 33P isotopic labeling [70] may help to identify AMF-plant associations with efficient energy rates of extra radical mycelium respiration when the mycorrhizal nutrient uptake pathway is active. This could contribute to expand our view on the interplay between nutrient uptake pathways in plants with mycorrhiza.

Figure 2. Simplified overview of the interaction between respiratory metabolism of plant organs and mycorrhiza, conditioned by the demand for ATP synthesis and P uptake. Photosynthetic soluble sugars are used in respiration in leaves or transported to the root in order to fuel respiration and produce carbon skeletons for the fungal symbiont. Soluble sugars and organic acids can be exported to the fungal symbiont to fuel respiration in both intra and extraradical mycelium. ATP is required for P uptake and transport across organisms. TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle. Modified from Hughes et al. [40].

2. Regulation of AOX Activity by N Availability

Nitrogen is a major component of the photosynthetic apparatus and is required by plants in greater quantities than any other mineral element. Almost all the N available for plants is present in the reduced form of nitrate (NO3−), ammonium (NH4+), organic compounds and molecular nitrogen (N2) in the air [71][72]. The major source of N in soils resides in the atmosphere, through both biological N2 fixation and the deposition of NO3− and NH4+ in precipitation. In soils, NH4+ and NO3− move towards roots through transpiration-driven mass flow because they are water soluble [73]. Both NH4+ and NO3− enter the plant cells via specific transporters [74][75]. In order to be incorporated, NO3− is reduced to NH4+ by nitrate reductase (NR) and nitrite reductase [76]. Then, NH4+ is further converted into glutamine and glutamate, in a reaction catalyzed by glutamine synthetase/glutamine 2-oxoglutarate amino-transferase (GS/GOGAT) cycle [75]. At the cellular level, nitrogen assimilation is finely regulated according to its supply and demand. Nitrogen controls the regulation of nitrate transporters, activities of nitrate and nitrite reductase, the functioning of primary metabolic pathways associated with the production of reducing equivalents and the production of organic acids required for N assimilation into amino acids [3].

There is a correlation between leaf N content and rates of respiration [77][78][79][80]. Short supply of N leads to decreasing rates of both photosynthesis and respiration by reducing protein turnover and increasing breakdown of nucleic acids and enzymes [12][81]. Under these circumstances, a minimum supply of TCA metabolites (e.g., 2-oxoglutarate, isocitrate, and citrate) may maintain optimum N assimilation and amino acid biosynthesis [82][83]. Indeed, TCA cycle enzymes fumarase, NAD-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, and NAD-dependent malic enzyme are up-regulated under low N [78][84], and protein degradation acts as an alternative respiratory substrate [36]. In this situation, AOX activity could play a role in maintaining the functioning of primary metabolism by allowing adjustments in energy efficiency of respiration. However, there are no studies that test the regulation of AOX activity in vivo under N limitation. Such a hypothetical role should be evaluated in plant species with constitutively high levels of both AOX protein and activity. Plants possess an AOX overcapacity [85][86][87][88][89], which is variable depending on the plant species and environmental conditions [86][89]. It is thought that this overcapacity eliminates the need for de novo AOX protein synthesis, granting alternative respiration the ability to respond to sudden changes in levels of reducing equivalents [85][86][89]. In this sense, a short supply of N in plant species with high levels of AOX protein, such as legumes, could induce a decrease of both AOX protein and capacity to some extent without compromising the accuracy of AOX activity measurements, allowing us to evaluate the in vivo role of AOX under stress. Preliminary results from our laboratory in Lotus japonicus have shown that total respiration decreases (via COX and AOX) in leaves and roots when plants grow under short supply of KNO3, in comparison with plants grown at sufficient KNO3 supply. Interestingly, a short supply of KNO3 induces an increase of the energy efficiency of respiration (via decreased contribution of AOX activity to total respiration) only in leaves (unpublished), which suggests the existence of a differential regulation between organs directed to maximize ATP synthesis in leaves, most likely for maintenance purposes.

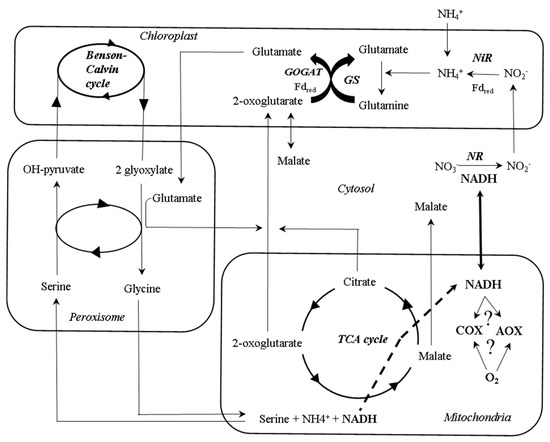

On the other hand, the source of N could be another regulatory factor of AOX activity in leaves. Classic studies have observed that the expression and activity of several glycolytic and TCA cycle enzymes were differentially affected following NH4+ or NO3− uptake [82][83][90], which could be accompanied with respiratory adjustments. It is known that nitrate uptake and its conversion to ammonium require large amounts of ATP and reducing equivalents [91][92][93]. However, respiration increases when ammonium is present as the main N source [94][95][96]. This has been explained as a consequence for the lack of the important reductant sink exerted by nitrate reductase, thus leading to an increase of reducing equivalents in cytosol, that are dissipated by mitochondrial electron transport chain. Under this scenario, AOX could play a significant role during this dissipation of reductants, considering its roles in maintaining the cell redox balance [85][97][98]. In this way, the accumulation of NH4+ and its associated toxicity is prevented by the action of the GS/GOGAT cycle activity [99] in parallel to the mitochondrial dissipation of reductants. In fact, previous studies have shown an increase in AOX capacity and enhanced of several AOX isoforms in plants grown under NH4+ supply [96][97][100][101][102]. Moreover, negative correlations between AOX capacity and nitrate concentrations were observed [96], although the electron flow through AOX under aerobic conditions can be important for the reduction of NO generation associated to nitrate reduction [103]. Interestingly, the growth of AOX-overexpressing plants is less restricted as compared to wild type (WT) Arabidopsis plants grown under NH4+ nutrition, although the metabolic causes of this phenotype remain uncertain [100]. The hypothetical role of AOX in conferring metabolic flexibility during NH4+ nutrition still needs to be tested by in vivo activity measurements (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A simplified schematic overview of the compartmentation of some of the interactions between primary metabolism pathways during ammonium and nitrate assimilation. Nitrate is mainly transported from roots to leaves via xylem, where it is converted into nitrite with the consumption of reducing equivalents in cytosol. In the chloroplast, the reducing power of light-activated electrons drives the conversion of nitrite to ammonium from cytosolic nitrate reductase (NR)-derived nitrite by a nitrite reductase (NiR) activity, and its assimilation by the GS/GOGAT cycle. 2-oxoglutarate which is required for ammonium assimilation, is exported to the chloroplast by a 2-oxoglutarate/malate translocator. Ammonium uptake bypasses the nitrate reductase reaction in cytosol, thus increasing the reducing equivalents available that can be dissipated during respiration. During photorespiration, the retrieval of CO2 and NH4+ during the glycine cleavage reaction in mitochondria leads to an increased NADH/NAD+ ratio in the mitochondrial matrix that has been suggested to be related to changes in AOX activity. TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

2.1. Regulation of AOX Activity in the Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis

Regulation of AOX Activity in the Rhizobium-Legume Symbiosis

Legumes are good candidates to study the regulation of AOX activity by N availability because these plants have been suggested to display faster rates of foliar AOX activity under stress as they constitutively express high levels of AOX protein under normal growth conditions [104][105][106]. In fact, measurements of in vivo AOX activity have been performed in leaves of six legumes species: common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), garden pea (Pisum sativum), barrel medic (Medicago truncatula), soybean (Glycine max), mung bean (Vigna radiata) and faba bean (Vicia faba). These experiments have been important to evaluate the regulation of the AOX activity under P limitation, high light, salinity, pathogen infection and variable temperatures [86][107][108][109][110][111]. Furthermore, legumes are suitable for the study of the regulation of AOX activity by N availability in roots because of their ability to establish symbiosis with a group of soil bacteria collectively designated as rhizobia. Rhizobia is a group of diazotrophs, most of them belonging to the α-proteobacteria, that include the genera Rhizobium, Mesorhizobium, Ensifer (formerly Sinorhizobium), Bradyrhizobium and Azorhizobium, among others [112]. The rhizobia-legume symbiosis provides a suitable biological system to evaluate variations in both nutrient status and metabolite levels in plant organs due to the exchange of carbon and nutrients between host plants and bacteroids (that is, the differentiated endosymbiotic form of the bacteria able to fix nitrogen).

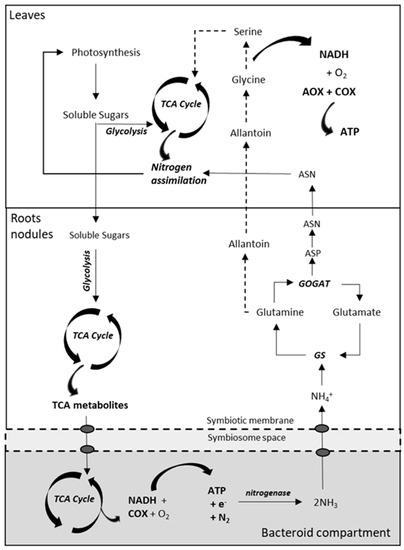

Legumes can fix atmospheric nitrogen (N2) through the nitrogenase activity that reduces N2 to NH3− and is located in the root nodule bacteria [113][114][115]. Biological N2 fixation in leguminous plants requires the development of a specific symbiotic relationship between rhizobia soil bacteria and the plant root in conditions of limited nitrogen availability in soil [116]. In bacteroids, the nitrogenase reaction requires a great deal of energy, consuming at least 16 ATP and four pairs of electrons for every molecule of N2 reduced to ammonia [116][117]. This energy is obtained from plant carbon compounds in the form of TCA cycle intermediates (fumarate, succinate or malate) via a dicarboxylic-acid transport system [117][118][119]. Similar to mycorrhizal symbiosis, the nodule imposes a carbon cost in roots that cannot exceed their nutritional benefit. However, it is unknown whether respiratory adjustments in nodulated roots contribute to the regulation of the carbon economy in legumes. In this sense, preliminary results from our laboratory obtained in roots of L. japonicus nodulated by Mesorhizobium loti revealed higher rates of total respiration via COX (and diminished AOX activity) when compared to non-nodulated roots of plants grown at low KNO3 (unpublished). These results are in agreement with the previous studies describing high rates of respiration in nodulated roots [120][121][122]. On the other hand, we observed similar rates of respiration in nodulated roots when compared to non-nodulated roots of plants grown at sufficient KNO3 (unpublished). Based on these results, it seems that the effect of rhizobia on root respiration could be related to an improved N status rather than to carbon costs of nodule maintenance and nitrogenase activity. Biological nitrogen fixation leads to the production of ammonium in bacteroids, which is transferred to the host plant through the symbiosome membrane and initially assimilated to glutamine, and then to either ureides or amides to ameliorate N status in leaves [115][119][123][124][125]. Similar to roots, rhizobia inoculation did not significantly change the activities of the two terminal oxidases in leaves of L. japonicus plants grown under KNO3 sufficiency, thus suggesting a similar N status between these plants. Furthermore, leaves of non-nodulated plants grown at low KNO3 displayed the lowest rates of ATP synthesis via decreased COX and AOX (unpublished). Based on these preliminary results, it seems that the activities of both COX and AOX in plant organs depend on N availability. Another regulatory factor of AOX activity in leaves could be determined by the type of nodule. The determinate legume root nodules, characteristic of some tropical legumes as soybean and common bean, primarily exports ureides (allantoin and allantoate) as fixed-N compounds to be metabolized in leaves. These compounds are converted to glycine, which in turn will be converted to serine as part of the photorespiration pathway that is associated to the mitochondrial release of ammonia in and its re-assimilation into nitrogenated compounds [118][126]. On the other hand, indeterminate nodules, characteristic of certain temperate legumes as barrel medic and pea, assimilate amides in the form of asparagine (Asn) and glutamine (Gln) [126][127], which are exported to the aerial part to be directly incorporated into leaf metabolism. This bypasses the production of reducing equivalents related to the decarboxylation of glycine to serine in leaf mitochondria [128] that is observed in determinate nodules, which could be associated with changes in AOX activity (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Simplified overview of the nitrogen-fixing pathways in nodulated legumes, conditioned by the demand for ATP synthesis for nitrogenase activity in determinate and indeterminate nodules. Soluble sugars are catabolized via glycolysis to respiratory substrates for the synthesis of TCA metabolites, which are transported across the peribacteroid and bacteroid membranes to fuel the TCA cycle and respiration in the bacteroid. The ammonia produced during nitrogenase activity is exported to the plant and assimilated by GS and GOGAT enzymes. In determinate nodules, glutamine is converted to ureides (allantoin), that are decarboxylated in metabolic pathways of photorespiration, contributing to the accumulation of NADH in mitochondria. In indeterminate nodules, glutamine and glutamate are further converted to asparagine and aspartate to be incorporated into the nitrogen metabolism of leaves. ASN, asparagine; ASP, aspartic acid; TCA, tricarboxylic acid cycle. Modified from Liu et al. [116].

Although nitrogenase enzyme requires O2 for ATP synthesis, this enzyme is extremely O2-labile, being inhibited above a certain O2 concentration. This was called “the oxygen paradox” [129]. In order to maintain respiration and ATP synthesis in the infected cells, the nodule displays several mechanisms for delivering a regulated flux of O2, while maintaining a free O2 concentration at low levels in infected cells. One of these mechanisms is the occurrence of an O2 diffusion barrier to the nodule central zone, where nitrogen-fixation takes place [130]. Moreover, it is thought that rates of bacteroid respiration are high enough to ensure a quick consumption of O2, as soon as the gas diffuses into the central zone to avoid its accumulation [131]. However, fast rates of nitrogenase activity would increase the demand for O2 concentration in the infected cells. To increase O2 diffusion to bacteroids, the infected cells contain leghemoglobin that acts as an O2 carrier. This is an iron protein with high affinity for O2, which regulates O2 diffusion from the cytosol to the bacteroid in adequate concentrations to fuel its respiration, preventing inhibition of nitrogenase [132][133]. Thus, the ability of the nodule to respond to sudden increases of O2 in infected cells is very important because of their repercussions on biological nitrogen fixation. AOX has been found in nodules infected by several species of rhizobia such as Bradyrhizobium japonicum and Rhizobium leguminosarum [134][135], although with lower abundance and capacity than any other tissue of the same plant as was described in soybean root nodules [135]. Thus, it is unlikely that AOX activity may play a significant role in nodule respiration as it does in plant cells [135][136]. However, the observed upregulation of AOX mRNA levels in senescent bean nodules was proposed to contribute to the redox balance in mitochondria [134]. Presently, there are no results of in vivo activities of COX and AOX in legumes nodules. Accurate estimates of the activities of COX and AOX in plant nodules would require in vivo measurements in bacteroid and mitochondria by using on-line liquid-phase systems [136][137][138]. They are worthy for the corroboration of the high energy efficiency of nodule respiration, which can be assumed to be tightly coordinated with the nitrogenase activity. This is because nodule mitochondria contain COX enzyme with high affinity for oxygen and nitrogenase activity depends on O2 consumption for ATP synthesis [139][140][141][142][143]. In fact, abiotic stressors result in the inhibition of carbon metabolism in host legumes as well as in the increase of nodule resistance to O2 diffusion in order to constrain respiration and nitrogenase activity and save carbon that will eventually become scarce [144]. It is worth mentioning the existence of different metabolic responses to Pi deficiency observed among legumes when biological nitrogen fixation is suppressed under Pi deficiency [118]. One of these responses is the enhancement of Pi uptake and recycling in nodules [124][145][146] that may lead to the use of alternative respiratory substrates of carbon compounds such as amino acids, as observed in the metabolic profiles performed during symbiotic nitrogen fixation in phosphorus-stressed common bean [147]. Although methodological improvements are still needed for the study of nodule respiration, it seems that measurements of both apparent nitrogenase activity and total nitrogenase activity, in combination with O2 isotope fractionation and metabolite profiling in plant organs, is a good starting point to understand how biological nitrogen fixation and plant respiratory metabolism are connected in legumes.

References

- Timothy S. George; Philippe Hinsinger; Benjamin Turner; Phosphorus in soils and plants – facing phosphorus scarcity. Plant and Soil 2016, 401, 1-6, 10.1007/s11104-016-2846-9.

- Jianbo Shen; Lixing Yuan; Junling Zhang; Haigang Li; Zhaohai Bai; Xinping Chen; Weifeng Zhang; Fusuo Zhang; Phosphorus Dynamics: From Soil to Plant1. Plant Physiology 2011, 156, 997-1005, 10.1104/pp.111.175232.

- Elena Vidal; Rodrigo A. Gutiérrez; A systems view of nitrogen nutrient and metabolite responses in Arabidopsis. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2008, 11, 521-529, 10.1016/j.pbi.2008.07.003.

- Hawkesford, M.; Horst, W.; Kichey, T.; Lambers, H.; Schjoerring, J.; Møller, I.S.; White, P. Functions of macronutrients. In Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants, 3rd ed.; Marchner, P., Ed.; Academic Press: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2012; pp. 135–189.

- William C. Plaxton; Hue T. Tran; Metabolic Adaptations of Phosphate-Starved Plants1. Plant Physiology 2011, 156, 1006-1015, 10.1104/pp.111.175281.

- Lambers, H.; Robinson, S.A.; Ribas-Carbo, M. Regulation of respiration in vivo. In Plant Respiration: From Cell to Ecosystem; Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration Series; Lambers, H., Ribas-Carbo, M., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 18, pp. 1–15.

- Wagner L. Araújo; Adriano Nunes-Nesi; Zoran Nikoloski; Lee J. Sweetlove; Alisdair R. Fernie; Metabolic control and regulation of the tricarboxylic acid cycle in photosynthetic and heterotrophic plant tissues. Plant, Cell & Environment 2012, 35, 1-21, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2011.02332.x.

- Shane, M.W.; Lambers, H. Cluster roots: A curiosity in context. In Root Physiology: From Gene to Function, 1st ed.; Lambers, H., Colmer, T.D., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands , 2005; pp. 101–125.

- Hans Lambers; Michael W. Shane; Michael D. Cramer; Stuart J. Pearse; Erik J. Veneklaas; Root Structure and Functioning for Efficient Acquisition of Phosphorus: Matching Morphological and Physiological Traits. Annals of Botany 2006, 98, 693-713, 10.1093/aob/mcl114.

- Lambers, H.; Brundrett, M.; Raven, J.; Hopper, S; Plant mineral nutrition in ancient landscapes: High plant species diversity on infertile soils is linked to functional diversity for nutritional strategies. Plant and Soil 2010, 334, 11-31.

- Graham Zemunik; Hans Lambers; Benjamin Turner; Étienne Laliberté; Rafael S. Oliveira; High abundance of non-mycorrhizal plant species in severely phosphorus-impoverished Brazilian campos rupestres. Plant and Soil 2018, 424, 255-271, 10.1007/s11104-017-3503-7.

- Lambers, H.; Chapin, F.S., III; Pons, T.L. Plant Physiological Ecology; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 10–95.

- Igor Florez-Sarasa; Hans Lambers; Xing Wang; Patrick Finnegan; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; The alternative respiratory pathway mediates carboxylate synthesis in white lupin cluster roots under phosphorus deprivation. Plant, Cell & Environment 2013, 37, 922-928, 10.1111/pce.12208.

- Michael W. Shane; Michael D. Cramer; Sachiko Funayama-Noguchi; Gregory R. Cawthray; A. Harvey Millar; David A. Day; Hans Lambers; Developmental Physiology of Cluster-Root Carboxylate Synthesis and Exudation in Harsh Hakea. Expression of Phosphoenolpyruvate Carboxylase and the Alternative Oxidase1. Plant Physiology 2004, 135, 549-560, 10.1104/pp.103.035659.

- G. C. Vanlerberghe; L. Mclntosh; Signals Regulating the Expression of the Nuclear Gene Encoding Alternative Oxidase of Plant Mitochondria. Plant Physiology 1996, 111, 589-595.

- Lambers, H.; Plaxton, W.C. Phosphorus: Back to the Roots. In Annual Plant Reviews Phosphorus Metabolism in Plants; Plaxton, W.C., Lambers, H., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 48, pp. 1–22.

- José López‐Bucio; Marı́a Fernanda Nieto-Jacobo; Verenice Ramı́rez-Rodrı́guez; Luis Rafael Herrera-Estrella; Organic acid metabolism in plants: from adaptive physiology to transgenic varieties for cultivation in extreme soils. Plant Science 2000, 160, 1-13, 10.1016/s0168-9452(00)00347-2.

- Ralitza Alexova; Clark Nelson; A. Harvey Millar; Temporal development of the barley leaf metabolic response to P i limitation. Plant, Cell & Environment 2017, 40, 645-657, 10.1111/pce.12882.

- Maria E. Theodorou; Ivor R. Elrifi; David H. Turpin; William C. Plaxton; Narayana M. Upadhyaya; C. William Parker; David S. Letham; Kieran F. Scott; Peter J. Dart; Effects of Phosphorus Limitation on Respiratory Metabolism in the Green Alga Selenastrum minutum. Plant Physiology 1991, 95, 1089-1095, 10.1104/pp.95.4.1089.

- Anna M. Rychter; Maria Mikulska; The relationship between phosphate status and cyanide-resistant respiration in bean roots. Physiologia Plantarum 1991, 79, 663-667, 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1990.790413.x.

- Marcel H. N. Hoefnagel; Frank Van Iren; Kees R. Libbenga; Linus H. W. Van Der Plas; Possible role of adenylates in the engagement of the cyanide-resistant pathway in nutrient-starved Catharanthus roseus cells. Physiologia Plantarum 1994, 90, 269-278, 10.1034/j.1399-3054.1994.900205.x.

- Hannah L. Parsons; Increased Respiratory Restriction during Phosphate-Limited Growth in Transgenic Tobacco Cells Lacking Alternative Oxidase. Plant Physiology 1999, 121, 1309-1320, 10.1104/pp.121.4.1309.

- Izabela Juszczuk; Eligio Malusá; Anna M. Rychter; Oxidative stress during phosphate deficiency in roots of bean plants (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Journal of Plant Physiology 2001, 158, 1299-1305, 10.1078/0176-1617-00541.

- Stephen M. Sieger; Brian K. Kristensen; Christine A. Robson; Sasan Amirsadeghi; Edward W. Y. Eng; Amal Abdel-Mesih; Ian M Møller; Greg C. Vanlerberghe; The role of alternative oxidase in modulating carbon use efficiency and growth during macronutrient stress in tobacco cells. Journal of Experimental Botany 2005, 56, 1499-1515, 10.1093/jxb/eri146.

- Ko Noguchi; Ichiro Terashima; Sachiko Funayama-Noguchi; Comparison of the response to phosphorus deficiency in two lupin species,Lupinus albusandL. angustifolius, with contrasting root morphology. Plant, Cell & Environment 2014, 38, 399-410, 10.1111/pce.12390.

- Greg C. Vanlerberghe; Alternative Oxidase: A Mitochondrial Respiratory Pathway to Maintain Metabolic and Signaling Homeostasis during Abiotic and Biotic Stress in Plants. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2013, 14, 6805-6847, 10.3390/ijms14046805.

- Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Gregory R. Cawthray; Antònia Romero-Munar; Jaume Flexas; Ricardo Aroca; Elena Baraza; Hans Lambers; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus colonization in Nicotiana tabacum decreases the rate of both carboxylate exudation and root respiration and increases plant growth under phosphorus limitation. Plant and Soil 2017, 416, 97-106, 10.1007/s11104-017-3188-y.

- Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Antònia Romero-Munar; Gregory R. Cawthray; Francisco Palma; Ricardo Aroca; Elena Baraza; Igor Florez-Sarasa; Hans Lambers; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Phosphorus concentration coordinates a respiratory bypass, synthesis and exudation of citrate, and the expression of high-affinity phosphorus transporters in Solanum lycopersicum. Plant, Cell & Environment 2018, 41, 865-875, 10.1111/pce.13155.

- M. A. Gonzalez-Meler; L. Giles; R. B. Thomas; James N Siedow; Metabolic regulation of leaf respiration and alternative pathway activity in response to phosphate supplyy. Plant, Cell & Environment 2001, 24, 205-215, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2001.00674.x.

- Campbell, C.D.; Sage, R.F; Interactions between the effects of atmospheric CO2 content and P nutrition on photosynthesis in white lupin (Lupinus albus L.). Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 29, 844–853.

- Christian Rm Hermans; John Hammond; Philip J. White; Nathalie Verbruggen; How do plants respond to nutrient shortage by biomass allocation?. Trends in Plant Science 2006, 11, 610-617, 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.10.007.

- Adriano Nunes-Nesi; Wagner L. Araújo; Toshihiro Obata; Alisdair R. Fernie; Regulation of the mitochondrial tricarboxylic acid cycle. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2013, 16, 335-343, 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.01.004.

- Jianbo Shen; Lixing Yuan; Junling Zhang; Haigang Li; Zhaohai Bai; Xinping Chen; Weifeng Zhang; Fusuo Zhang; Phosphorus Dynamics: From Soil to Plant. Plant Physiology 2011, 156, 997-1005, 10.1104/pp.111.175232.

- Chunyuan Huang; Ute Roessner; Ira Eickmeier; Yusuf Genc; Damien Callahan; Neil J Shirley; Peter Langridge; Antony Bacic; Antony Bacic; Metabolite Profiling Reveals Distinct Changes in Carbon and Nitrogen Metabolism in Phosphate-Deficient Barley Plants (Hordeum vulgare L.). Plant and Cell Physiology 2008, 49, 691-703, 10.1093/pcp/pcn044.

- Charles Warren; How does P affect photosynthesis and metabolite profiles of Eucalyptus globulus?. Tree Physiology 2011, 31, 727-739, 10.1093/treephys/tpr064.

- Wagner L. Araújo; Takayuki Tohge; Kimitsune Ishizaki; Christopher J. Leaver; Alisdair R. Fernie; Protein degradation – an alternative respiratory substrate for stressed plants. Trends in Plant Science 2011, 16, 489–498, 10.1016/j.tplants.2011.05.008.

- Tatjana M. Hildebrandt; Adriano Nunes-Nesi; Wagner L. Araújo; Hans-Peter Braun; Amino Acid Catabolism in Plants. Molecular Plant 2015, 8, 1563-1579, 10.1016/j.molp.2015.09.005.

- Bożena Szal; Anna Podgórska; The role of mitochondria in leaf nitrogen metabolism. Plant, Cell & Environment 2012, 35, 1756-1768, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02559.x.

- Mark C. Brundrett; Leho Tedersoo; Evolutionary history of mycorrhizal symbioses and global host plant diversity. New Phytologist 2018, 220, 1108-1115, 10.1111/nph.14976.

- Dieter Strack; Thomas Fester; Bettina Hause; Willibald Schliemann; Michael Walter; Arbuscular mycorrhiza: biological, chemical, and molecular aspects. Journal of Chemical Ecology 2003, 29, 1955–1979.

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis, 3th ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2008; pp. 1–769.

- Réka Nagy; David Drissner; Nikolaus Amrhein; Iver Jakobsen; Marcel Bucher; Mycorrhizal phosphate uptake pathway in tomato is phosphorus-repressible and transcriptionally regulated. New Phytologist 2008, 181, 950-959, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02721.x.

- Glaciela Kaschuk; Thomas W. Kuyper; P.A. Leffelaar; Mariangela Hungria; Ken E. Giller; Are the rates of photosynthesis stimulated by the carbon sink strength of rhizobial and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses?. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2009, 41, 1233-1244, 10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.03.005.

- John K. Hughes; Angela Hodge; Alastair Fitter; Owen K. Atkin; Mycorrhizal respiration: implications for global scaling relationships. Trends in Plant Science 2008, 13, 583-588, 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.010.

- B. Bago; Carbon Metabolism and Transport in Arbuscular Mycorrhizas. Plant Physiology 2000, 124, 949-958, 10.1104/pp.124.3.949.

- Rob Baas; Daan Kuiper; Effects of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal infection and phosphate on Plantago major ssp. pleiosperma in relation to internal cytokinin concentrations. Physiologia Plantarum 1989, 76, 211-215, 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1989.tb05634.x.

- A. Hodge; Impact of elevated CO2 on mycorrhizal associations and implications for plant growth. Biology and Fertility of Soils 1996, 23, 388-398, 10.1007/bf00335912.

- David Johnson; Jonathan R. Leake; D.J Read; Transfer of recent photosynthate into mycorrhizal mycelium of an upland grassland: short-term respiratory losses and accumulation of 14C. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 2002, 34, 1521-1524, 10.1016/s0038-0717(02)00126-8.

- Natalija Hohnjec; Martin F. Vieweg; Alfred Pühler; Anke Becker; Helge Küster; Overlaps in the Transcriptional Profiles of Medicago truncatula Roots Inoculated with Two Different Glomus Fungi Provide Insights into the Genetic Program Activated during Arbuscular Mycorrhiza. Plant Physiology 2005, 137, 1283-1301, 10.1104/pp.104.056572.

- Willibald Schliemann; Christian Ammer; Dieter Strack; Metabolite profiling of mycorrhizal roots of Medicago truncatula. Phytochemistry 2008, 69, 112-146, 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.06.032.

- Jérôme Laparre; Mathilde Malbreil; Fabien Létisse; Christophe Roux; Guillaume Becard; Virginie Puech-Pages; Jean-Charles Portais; Combining Metabolomics and Gene Expression Analysis Reveals that Propionyl- and Butyryl-Carnitines Are Involved in Late Stages of Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis. Molecular Plant 2014, 7, 554-566, 10.1093/mp/sst136.

- Megan H. Ryan; Mark Tibbett; T. Edmonds-Tibbett; L. D. B. Suriyagoda; Hans Lambers; G. R. Cawthray; J. Pang; Carbon trading for phosphorus gain: the balance between rhizosphere carboxylates and arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant phosphorus acquisition. Plant, Cell & Environment 2012, 35, 2170-2180, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2012.02547.x.

- Nazanin K. Nazeri; Hans Lambers; Mark Tibbett; Megan H. Ryan; Moderating mycorrhizas: arbuscular mycorrhizas modify rhizosphere chemistry and maintain plant phosphorus status within narrow boundaries. Plant, Cell & Environment 2013, 37, 911-921, 10.1111/pce.12207.

- Antònia Romero-Munar; Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Jaume Flexas; Elena Baraza; Igor Florez-Sarasa; Alisdair Robert Fernie; Javier Gulías; Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Symbiosis withArundo donaxDecreases Root Respiration and Increases Both Photosynthesis and Plant Biomass Accumulation. Plant, Cell & Environment 2017, 40, 1115-1126, 10.1111/pce.12902.

- Stuart Pearse; Erik J. Veneklaas; Greg Cawthray; Mike D. A. Bolland; Hans Lambers; Carboxylate composition of root exudates does not relate consistently to a crop species’ ability to use phosphorus from aluminium, iron or calcium phosphate sources. New Phytologist 2007, 173, 181-190, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01897.x.

- Jiayin Pang; Megan H. Ryan; Mark Tibbett; Gregory R. Cawthray; Kadambot H. M. Siddique; Mike D. A. Bolland; Matthew D. Denton; Hans Lambers; Variation in morphological and physiological parameters in herbaceous perennial legumes in response to phosphorus supply. Plant and Soil 2009, 331, 241-255, 10.1007/s11104-009-0249-x.

- John A. Raven; Hans Lambers; Sally E. Smith; Mark Westoby; Costs of acquiring phosphorus by vascular land plants: patterns and implications for plant coexistence. New Phytologist 2018, 217, 1420-1427, 10.1111/nph.14967.

- D. P. Stribley; P. B. Tinker; J. H. Rayner; RELATION OF INTERNAL PHOSPHORUS CONCENTRATION AND PLANT WEIGHT IN PLANTS INFECTED BY VESICULAR-ARBUSCULAR MYCORRHIZAS. New Phytologist 1980, 86, 261-266, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1980.tb00786.x.

- Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Antònia Romero-Munar; David Alonso; Ricardo Aroca; Elena Baraza; Jaume Flexas; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Respiratory ATP cost and benefit of arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis with Nicotiana tabacum at different growth stages and under salinity. Journal of Plant Physiology 2017, 218, 243-248, 10.1016/j.jplph.2017.08.012.

- Sally E. Smith; F. Andrew Smith; Iver Jakobsen; Functional diversity in arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses: the contribution of the mycorrhizal P uptake pathway is not correlated with mycorrhizal responses in growth or total P uptake. New Phytologist 2004, 162, 511-524, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01039.x.

- Marcel Bucher; Bettina Hause; Franziska Krajinski; Helge Küster; Through the doors of perception to function in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbioses. New Phytologist 2014, 204, 833-840, 10.1111/nph.12862.

- Stephanie J. Watts-Williams; Iver Jakobsen; Timothy Cavagnaro; Mette Grønlund; Local and distal effects of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization on direct pathway Pi uptake and root growth in Medicago truncatula. Journal of Experimental Botany 2015, 66, 4061-4073, 10.1093/jxb/erv202.

- Marcel Bucher; Functional biology of plant phosphate uptake at root and mycorrhiza interfaces. New Phytologist 2007, 173, 11-26, 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2006.01935.x.

- Vladimir Karandashov; Marcel Bucher; Symbiotic phosphate transport in arbuscular mycorrhizas. Trends in Plant Science 2005, 10, 22-29, 10.1016/j.tplants.2004.12.003.

- Ruairidh J. H. Sawers; Simon F. Svane; Clement Quan; Mette Grønlund; Barbara Wozniak; Mesfin-Nigussie Gebreselassie; Eliécer González-Muñoz; Ricardo A. Chavez Montes; Ivan Baxter; Jérôme Goudet; et al.Iver JakobsenUta. Paszkowski Phosphorus acquisition efficiency in arbuscular mycorrhizal maize is correlated with the abundance of root-external hyphae and the accumulation of transcripts encoding PHT1 phosphate transporters. New Phytologist 2017, 214, 632-643, 10.1111/nph.14403.

- Sally E. Smith; Iver Jakobsen; Mette Grønlund; F. Andrew Smith; Roles of Arbuscular Mycorrhizas in Plant Phosphorus Nutrition: Interactions between Pathways of Phosphorus Uptake in Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Roots Have Important Implications for Understanding and Manipulating Plant Phosphorus Acquisition1. Plant Physiology 2011, 156, 1050-1057, 10.1104/pp.111.174581.

- E. Facelli; T. Duan; S E. Smith; H.M. Christophersen; J M. Facelli; F A. Smith; Opening the black box: outcomes of interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) and non-host genotypes of Medicago depend on fungal identity, interplay between P uptake pathways and external P supply. Plant, Cell & Environment 2013, 37, 1382-1392, 10.1111/pce.12237.

- Catarina Campos; Hélia Cardoso; Amaia Nogales; Jan Svensson; Juan Antonio López-Ráez; María J. Pozo; Tânia Nobre; Carolin Schneider; Birgit Arnholdt-Schmitt; Intra and Inter-Spore Variability in Rhizophagus irregularis AOX Gene. PLOS ONE 2015, 10, 1-24, 10.1371/journal.pone.0142339.

- Carl R. Fellbaum; Jerry A. Mensah; Adam J. Cloos; Gary E. Strahan; Philip E. Pfeffer; E. Toby Kiers; Heike Bücking; Fungal nutrient allocation in common mycorrhizal networks is regulated by the carbon source strength of individual host plants. New Phytologist 2014, 203, 646-656, 10.1111/nph.12827.

- Alwyn Williams; Lokeshwaran Manoharan; Nicholas P. Rosenstock; Pål Axel Olsson; Katarina Hedlund; Long-term agricultural fertilization alters arbuscular mycorrhizal fungal community composition and barley (Hordeum vulgare) mycorrhizal carbon and phosphorus exchange. New Phytologist 2016, 213, 874-885, 10.1111/nph.14196.

- A.J. Miller; M. D. Cramer; Root nitrogen acquisition and assimilation. Plant Ecophysiology 2005, 4, 1-36, 10.1007/1-4020-4099-7_1.

- P J Lea; R.A. Azevedo; Nitrogen use efficiency. 2. Amino acid metabolism. Annals of Applied Biology 2007, 151, 269-275, 10.1111/j.1744-7348.2007.00200.x.

- Barber, S. Soil Nutrient Bioavailability: A Mechanistic Approach, 2nd ed.; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1995; p. 384.

- Heinz Rennenberg; Henning Wildhagen; B. Ehlting; Nitrogen nutrition of poplar trees. Plant Biology 2010, 12, 275-291, 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00309.x.

- Honghao Gan; Yu Jiao; Jingbo Jia; Xinli Wang; Hong Li; Wenguang Shi; Changhui Peng; Andrea Polle; Zhi-Bin Luo; Phosphorus and nitrogen physiology of two contrasting poplar genotypes when exposed to phosphorus and/or nitrogen starvation. Tree Physiology 2015, 36, 22-38, 10.1093/treephys/tpv093.

- Guohua Xu; Xiaorong Fan; A. J. Miller; Plant Nitrogen Assimilation and Use Efficiency. Annual Review of Plant Biology 2012, 63, 153-182, 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105532.

- Ichiro Terashima; John R Evans; Effects of Light and Nitrogen Nutrition on the Organization of the Photosynthetic Apparatus in Spinach. Plant and Cell Physiology 1988, 29, 143–155, 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pcp.a077461.

- Amane Makino; Barry Osmond; Effects of Nitrogen Nutrition on Nitrogen Partitioning between Chloroplasts and Mitochondria in Pea and Wheat. Plant Physiology 1991, 96, 355-362, 10.1104/pp.96.2.355.

- George T. Byrd; Rowan F. Sage; R. Harold Brown; A Comparison of Dark Respiration between C3 and C4 Plants. Plant Physiology 1992, 100, 191-198, 10.1104/pp.100.1.191.

- Christopher H. Lusk; Peter B. Reich; Relationships of leaf dark respiration with light environment and tissue nitrogen content in juveniles of 11 cold-temperate tree species. Oecologia 2000, 123, 318-329, 10.1007/s004420051018.

- Céline Richard-Molard; Anne Krapp; François Brun; Bertrand Ney; Françoise Daniel-Vedele; Sylvain Chaillou; Plant response to nitrate starvation is determined by N storage capacity matched by nitrate uptake capacity in two Arabidopsis genotypes. Journal of Experimental Botany 2008, 59, 779-791, 10.1093/jxb/erm363.

- Wolf-Rüdiger Scheible; Agustin Gonzalez-Fontes; Marianne Lauerer; Bernd Müller-Röber; Michel Caboche; Mark Stitt; Nitrate Acts as a Signal to Induce Organic Acid Metabolism and Repress Starch Metabolism in Tobacco. The Plant Cell 1997, 9, 783-789, 10.2307/3870432.

- Muriel Lancien; Sylvie Ferrario-Méry; Yvette Roux; Evelyne Bismuth; Céline Masclaux; Bertrand Hirel; Pierre Gadal; Michael Hodges; Simultaneous Expression of NAD-Dependent Isocitrate Dehydrogenase and Other Krebs Cycle Genes after Nitrate Resupply to Short-Term Nitrogen-Starved Tobacco. Plant Physiology 1999, 120, 717-726, 10.1104/pp.120.3.717.

- Noguchi, K.; Terashima, I; Responses of spinach leaf mitochondria to low N availablity. Plant Cell Environ. 2006, 29, 710–719.

- Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Allison E. McDonald; Hans Lambers; Alisdair R. Fernie; Igor Florez-Sarasa; An In Vivo Perspective of the Role(s) of the Alternative Oxidase Pathway. Trends in Plant Science 2018, 23, 206-219, 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.11.006.

- Igor Florez-Sarasa; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Kevin Schwahn; Zoran Nikoloski; Alisdair R. Fernie; Jaume Flexas; Unravelling the in vivo regulation and metabolic role of the alternative oxidase pathway in C3 species under photoinhibitory conditions. New Phytologist 2016, 212, 66-79, 10.1111/nph.14030.

- F. F. Millenaar; Regulation of Alternative Oxidase Activity in Six Wild Monocotyledonous Species. An in Vivo Study at the Whole Root Level. Plant Physiology 2001, 126, 376-387, 10.1104/pp.126.1.376.

- Craig Macfarlane; Lee D. Hansen; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Igor Florez-Sarasa; Plant mitochondria electron partitioning is independent of short-term temperature changes. Plant, Cell & Environment 2009, 32, 585-591, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2009.01953.x.

- Allan G. Rasmusson; Alisdair R. Fernie; Joost T. Van Dongen; Alternative oxidase: a defence against metabolic fluctuations?. Physiologia Plantarum 2009, 137, 371-382, 10.1111/j.1399-3054.2009.01252.x.

- M. Stitt; Nitrate regulation of metabolism and growth. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 1999, 2, 178-186, 10.1016/s1369-5266(99)80033-8.

- Hachiya, T.; Terashima, I.; Noguchi, K; Increase in respiratory cost at high growth temperature is attributed to high protein turnover cost in Petunia x hybrida petals. Plant Cell Environ. 2007, 30, 1269–1283.

- Graham Noctor; Christine H. Foyer; A re-evaluation of the ATP :NADPH budget during C3 photosynthesis: a contribution from nitrate assimilation and its associated respiratory activity?. Journal of Experimental Botany 1998, 49, 1895-1908, 10.1093/jxb/49.329.1895.

- Ingeborg Scheurwater; David T. Clarkson; Judith V. Purves; Geraldine Van Rijt; Leslie R. Saker; Rob Welschen; Hans Lambers; Relatively large nitrate efflux can account for the high specific respiratory costs for nitrate transport in slow-growing grass species. Plant and Soil 1999, 215, 123-134, 10.1023/a:1004559628401.

- Dev T. Britto; Herbert J Kronzucker; NH4+ toxicity in higher plants: a critical review. Journal of Plant Physiology 2002, 159, 567-584, 10.1078/0176-1617-0774.

- Matthew A. Escobar; Daniela A. Geisler; Allan G. Rasmusson; Reorganization of the alternative pathways of the Arabidopsis respiratory chain by nitrogen supply: opposing effects of ammonium and nitrate. The Plant Journal 2006, 45, 775-788, 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2005.02640.x.

- Takushi Hachiya; Chihiro K. Watanabe; Carolina Boom; Danny Tholen; Kentaro Takahara; Maki Kawai-Yamada; Hirofumi Uchimiya; Yukifumi Uesono; Ichiro Terashima; Ko Noguchi; et al. Ammonium-dependent respiratory increase is dependent on the cytochrome pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana shoots. Plant, Cell & Environment 2010, 33, 1888-1897, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2010.02189.x.

- Takushi Hachiya; Ko Noguchi; Integrative response of plant mitochondrial electron transport chain to nitrogen source. Plant Cell Reports 2010, 30, 195-204, 10.1007/s00299-010-0955-0.

- Anna Podgórska; Radosław Mazur; Monika Ostaszewska-Bugajska; Katsiaryna Kryzheuskaya; Kacper Dziewit; Klaudia Borysiuk; Agata Wdowiak; Maria Burian; Allan G. Rasmusson; Bożena Szal; et al. Efficient Photosynthetic Functioning of Arabidopsis thaliana Through Electron Dissipation in Chloroplasts and Electron Export to Mitochondria Under Ammonium Nutrition. Frontiers in Plant Science 2020, 103, 1-8, 10.3389/fpls.2020.00103.

- Raquel Esteban; Idoia Ariz; Cristina Cruz; Jose Fernando Moran; Review: Mechanisms of ammonium toxicity and the quest for tolerance. Plant Science 2016, 248, 92-101, 10.1016/j.plantsci.2016.04.008.

- Silvia Frechilla; Berta Lasa; Manolitxi Aleu; Nerea Juanarena; Carmen Lamsfus; Pedro M. Aparicio-Tejo; Short-term ammonium supply stimulates glutamate dehydrogenase activity and alternative pathway respiration in roots of pea plants. Journal of Plant Physiology 2002, 159, 811-818, 10.1078/0176-1617-00675.

- Berta Lasa; Silvia Frechilla; Pedro M. Aparicio-Tejo; Carmen Lamsfus; Alternative pathway respiration is associated with ammonium ion sensitivity in spinach and pea plants. Plant Growth Regulation 2002, 37, 49-55, 10.1023/a:1020312806239.

- Patterson, K.; Cakmak, T.; Cooper, A.; Lager, I.; Rasmusson, A.G.; Escobar, M.A; Distinct signalling athways and transcriptome response signatures differentiate ammonium- and nitrate-supplied plants. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1486–1501.

- Kapuganti J. Gupta; Aprajita Kumari; Igor Florez-Sarasa; Alisdair R Fernie; Abir U. Igamberdiev; Interaction of nitric oxide with the components of the plant mitochondrial electron transport chain. Journal of Experimental Botany 2018, 69, 3413-3424, 10.1093/jxb/ery119.

- Anthony Kearns; James Whelan; Susan Young; Thomas E. Elthon; David A. Day; Tissue-Specific Expression of the Alternative Oxidase in Soybean and Siratro. Plant Physiology 1992, 99, 712-717, 10.1104/pp.99.2.712.

- Patrick Finnegan; James Whelan; A. Harvey Millar; Q. Zhang; M. K. Smith; J. T. Wiskich; David A. Day; Differential expression of the multigene family encoding the soybean mitochondrial alternative oxidase. Plant Physiology 1997, 114, 455-466, 10.1104/pp.114.2.455.

- Crystal Sweetman; Kathleen L. Soole; Colin Jenkins; David A. Day; Genomic structure and expression of alternative oxidase genes in legumes. Plant, Cell & Environment 2018, 42, 71-84, 10.1111/pce.13161.

- Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Igor Florez-Sarasa; María José Clemente-Moreno; Haytem Mhadhbi; Jaume Flexas; Alisdair R. Fernie; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Salinity tolerance is related to cyanide-resistant alternative respiration in Medicago truncatula under sudden severe stress. Plant, Cell & Environment 2016, 39, 2361-2369, 10.1111/pce.12776.

- Marwa Batnini; Néstor Fernández Del-Saz; Mateu Fullana-Pericàs; Francisco Palma; Imen Haddoudi; Moncef Mrabet; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Haythem Mhadhbi; The alternative oxidase pathway is involved in optimizing photosynthesis in Medicago truncatula infected by Fusarium oxysporum and Rhizoctonia solani. Physiologia Plantarum 2020, -, -, 10.1111/ppl.13080.

- M. A. Gonzalez-Meler; L. Giles; R. B. Thomas; James N Siedow; Metabolic regulation of leaf respiration and alternative pathway activity in response to phosphate supply. Plant, Cell & Environment 2001, 24, 205-215, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.2001.00674.x.

- Gonzàlez-Meler, M.A.; Siedow, J.N; Inhibition of respiratory enzymes by elevated CO2: Does it matter at the intact tissue and whole plant levels. Tree Physiol. 1999, 19, 253–259.

- María C. Martí; Igor Florez-Sarasa; Daymi Camejo; Miquel Ribas-Carbó; Juan J. Lázaro; Francisca Sevilla; Ana Jiménez; Response of mitochondrial thioredoxin PsTrxo1, antioxidant enzymes, and respiration to salinity in pea (Pisum sativum L.) leaves. Journal of Experimental Botany 2011, 62, 3863-3874, 10.1093/jxb/err076.

- Teodoro Coba De La Peña; José J. Pueyo; Legumes in the reclamation of marginal soils, from cultivar and inoculant selection to transgenic approaches. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 2011, 32, 65-91, 10.1007/s13593-011-0024-2.

- Shin Okazaki; Takakazu Kaneko; Shusei Sato; Kazuhiko Saeki; Hijacking of leguminous nodulation signaling by the rhizobial type III secretion system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 17131-17136, 10.1073/pnas.1302360110.

- Benjamin Gourion; Fathi Berrabah; Pascal Ratet; Gary Stacey; Rhizobium–legume symbioses: the crucial role of plant immunity. Trends in Plant Science 2015, 20, 186-194, 10.1016/j.tplants.2014.11.008.

- Catherine Masson-Boivin; Joel L Sachs; Symbiotic nitrogen fixation by rhizobia — the roots of a success story. Current Opinion in Plant Biology 2018, 44, 7-15, 10.1016/j.pbi.2017.12.001.

- Teodoro Coba De La Peña; Elena Fedorova; José J. Pueyo; M. Mercedes Lucas; The Symbiosome: Legume and Rhizobia Co-evolution toward a Nitrogen-Fixing Organelle?. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 8, 2229, 10.3389/fpls.2017.02229.

- S. Tajima; H. Kouchi; Metabolism and Compartmentation of Carbon and Nitrogen in Legume Nodules. Plant-microbe Interactions 2 1997, 29, 27-60, 10.1007/978-1-4615-6053-1_2.

- Ailin Liu; Carolina A. Contador; Kejing Fan; Hon-Ming Lam; Interaction and Regulation of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Metabolisms in Root Nodules of Legumes. Frontiers in Plant Science 2018, 9, 1860, 10.3389/fpls.2018.01860.

- Emma Lodwig; Arthur Hosie; A. Bourdes; K. Findlay; David Allaway; R. Karunakaran; J A Downie; Philip S. Poole; Amino-acid cycling drives nitrogen fixation in the legume–Rhizobium symbiosis. Nature 2003, 422, 722-726, 10.1038/nature01527.

- Rao, T.P.; Ito, O. Differences in root system morphology and root respiration in relation to nitrogen uptake among six crop species. Jpn. Agric. Res. Q. 1998, 32, 97–104.

- Schulze, J.; Beschow, H.; Adgo, E.; Merbach, W. Efficiency of N2 fixation in Vicia faba L. in combination with different Rhizobium leguminosarum strains. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2000, 163, 367–373.

- Mortimer, P.E.; Pérez-Fernández, M.A.; Valentine, A.J. The role of arbuscular mycorrhizal colonization in the carbon and nutrient economy of the tripartite symbiosis with nodulated Phaseolus vulgaris. S. Biol. Biochem. 2008, 40, 1019–1027.

- Wang, Y.Y.; Hsu, P.K.; Tsay, Y.F. Uptake, allocation and signaling of nitrate. Trends Plant Sci. 2012, 17, 458–467.

- Udvardi, M.; Poole, P.S. Transport and metabolism in legume-rhizobia symbioses. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2013, 64, 781–805.

- Downie, J.A. Legume nodulation. Curr. Biol. 2014, 24, 184–190.

- Winkler, R.D.; Blevins, D.G.; Polacco, J.C.; Randall, D.D; Ureide catabolism in soybeans. II. Pathway of catabolism in intact leaf tissue. Plant Physiol. 1987, 83, 585–591.

- Sprent, J.I. Legume Nodulation: A Global Perspective; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 1–183.

- Adriano Nunes-Nesi; Alisdair R. Fernie; Mark Stitt; Metabolic and Signaling Aspects Underpinning the Regulation of Plant Carbon Nitrogen Interactions. Molecular Plant 2010, 3, 973-996, 10.1093/mp/ssq049.

- Kathleen Marchal; J. Vanderleyden; The "oxygen paradox" of dinitrogen-fixing bacteria. Biology and Fertility of Soils 2000, 30, 363-373, 10.1007/s003740050017.

- Felix D. Dakora; Craig A. Atkins; Adaptation of Nodulated Soybean (Glycine max L. Merr.) to Growth in Rhizospheres Containing Nonambient pO2. Plant Physiology 1991, 96, 728-736, 10.1104/pp.96.3.728.

- Sm Brown; Kb Walsh; Anatomy of the Legume Nodule Cortex With Respect to Nodule Permeability. Functional Plant Biology 1994, 21, 49-68, 10.1071/pp9940049.

- A. J. Gordon; F. R. Minchin; Leif Skot; C. L. James; Stress-Induced Declines in Soybean N2 Fixation Are Related to Nodule Sucrose Synthase Activity. Plant Physiology 1997, 114, 937-946, 10.1104/pp.114.3.937.

- Becana, M.; Navascués, J.; Pérez-Rontomé, C.; Walker, F.A.; Desbois, A.; Abian, J. Leghemoglobins with nitrated hemes in legume root nodules. In Biological Nitrogen Fixation; Bruijn, F.J., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 705–713.

- Manuel A Matamoros; Nieves Fernández-García; Stefanie Wienkoop; Jorge Loscos; Ana Saiz; Manuel Becana; Mitochondria are an early target of oxidative modifications in senescing legume nodules. New Phytologist 2013, 197, 873-885, 10.1111/nph.12049.

- A. Harvey Millar; Patrick Finnegan; James Whelan; J. J. Drevon; David A. Day; Expression and kinetics of the mitochondrial alternative oxidase in nitrogen-fixing nodules of soybean roots. Plant, Cell & Environment 1997, 20, 1273-1282, 10.1046/j.1365-3040.1997.d01-25.x.

- James H. Bryce; David A. Day; Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Activity in Mitochondria from Soybean Nodules and Cotyledons. Journal of Experimental Botany 1990, 41, 961-967, 10.1093/jxb/41.8.961.

- David A. Day; G. Dean Price; P. M. Gresshoff; Isolation and oxidative properties of mitochondria and bacteroids from soybean root nodules. Protoplasma 1986, 134, 121-129, 10.1007/bf01275710.

- Wai Yan Cheah; Pau Loke Show; Jo-Shu Chang; Tau Chuan Ling; Joon Ching Juan; Biosequestration of atmospheric CO 2 and flue gas-containing CO 2 by microalgae. Bioresource Technology 2015, 184, 190-201, 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.11.026.

- F. J. Bergersen; G. L. Turner; Leghaemoglobin and the Supply of O2 to Nitrogen-fixing Root Nodule Bacteroids: Presence of Two Oxidase Systems and ATP Production at Low Free O2 Concentration. Journal of General Microbiology 1975, 91, 345-354, 10.1099/00221287-91-2-345.

- F. J. Bergersen; G. L. Turner; Properties of Terminal Oxidase Systems of Bacteroids from Root Nodules of Soybean and Cowpea and of N2-fixing Bacteria Grown in Continuous Culture. Microbiology 1980, 118, 235-252, 10.1099/00221287-118-1-235.

- A. Harvey Millar; David A. Day; F. J. Bergersen; Microaerobic respiration and oxidative phosphorylation by soybean nodule mitochondria: implications for nitrogen fixation. Plant, Cell & Environment 1995, 18, 715-726, 10.1111/j.1365-3040.1995.tb00574.x.

- Ries Visser; Hans Lambers; Growth and the efficiency of root respiration of Pisum sativum as dependent on the source of nitrogen. Physiologia Plantarum 1983, 58, 533-543, 10.1111/j.1399-3054.1983.tb05739.x.

- O Preisig; R Zufferey; L Thöny-Meyer; C A Appleby; H Hennecke; A high-affinity cbb3-type cytochrome oxidase terminates the symbiosis-specific respiratory chain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum. Journal of Bacteriology 1996, 178, 1532-1538, 10.1128/jb.178.6.1532-1538.1996.

- Miguel López-Gómez; Jose Antonio Herrera Cervera; Carmen Iribarne; Noel A. Tejera; Carmen Lluch; Growth and nitrogen fixation in Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula under NaCl stress: Nodule carbon metabolism. Journal of Plant Physiology 2008, 165, 641-650, 10.1016/j.jplph.2007.05.009.

- Xiurong Wang; Jianbo Shen; Hong Liao; Acquisition or utilization, which is more critical for enhancing phosphorus efficiency in modern crops?. Plant Science 2010, 179, 302-306, 10.1016/j.plantsci.2010.06.007.

- L. Qin; Jing Zhao; Jiang Tian; Liyu Chen; Zhaoan Sun; Yongxiang Guo; Xing Lu; Mian Gu; Guohua Xu; Hong Liao; et al. The high-affinity phosphate transporter GmPT5 regulates phosphate transport to nodules and nodulation in soybean. Plant Physiology 2012, 159, 1634-1643, 10.1104/pp.112.199786.

- Georgina Hernández; Oswaldo Valdés‐López; Mario Ramírez; Nicolas Goffard; Georg Weiller; Rosaura Aparicio-Fabre; Sara Isabel Fuentes; Alexander Erban; Joachim Kopka; Michael K. Udvardi; et al.Carroll P. Vance Global changes in the transcript and metabolic profiles during symbiotic nitrogen fixation in phosphorus-stressed common bean plants. Plant Physiology 2009, 151, 1221-1238, 10.1104/pp.109.143842.