1. Introduction

The activity of many proteins is strongly influenced by their state of protonation. Therefore, intracellular and extracellular pH have to be tightly controlled to allow normal cell function. In healthy tissue, intracellular pH (pH

i) is set to around neutral, while extracellular pH (pH

e) is slightly alkaline

[1][2][1,2]. In tumors, however, alterations in cell metabolism and the acid/base regulator machinery result in drastic changes in intracellular and extracellular pH, with a slightly alkaline pH

i and acidic pH

e, which can drop down to values as low as 6.5

[3][4][5][3,4,5]. This extreme pH gradient seems to be a ubiquitous feature of malignant tumors, which appears already at an early stage of carcinogenesis, independent from the tumor’s origin and genetic background

[6][7][6,7]. Alterations in intracellular and extracellular pH, in turn, trigger a variety of physiological responses, which drive tumor progression. The slight increase in pH

i supports cell proliferation and inhibits apoptosis

[8][9][10][11][8,9,10,11]. Furthermore, a high pH

i activates cofilin, which supports cell migration by reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton

[12][13][12,13]. Finally, the intracellular alkalinization enhances glycolysis, which results in an increased production of acid and exacerbates extracellular acidification. Extracellular acidification can kill adjacent host cells and suppresses an immune response by inhibiting T-cell activation and impaired chemotaxis

[14][15][14,15]. Furthermore, the low pH

e supports degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM) and thereby contributes to tumor cell migration and invasion

[13][16][13,16].

pH regulation in tumor cells is governed by the concerted interplay between various acid/base transporters and carbonic anhydrases. The major pH regulator in cancer cells is the Na

+/H

+ exchanger 1 (NHE1). The expression of NHE1 is upregulated already in an early stage in tumorigenesis

[6]. Oncogene-induced activation of NHE1 drives both intracellular alkalization and extracellular acidification, and was therefore suggested to play a key role in the malignant transformation of solid tumors

[6][17][6,17]. Furthermore, NHE1, which accumulates in the leading edge of migrating cells, has been attributed a central role in cell migration and invasion

[18][19][20][21][18,19,20,21]. However, other NHE isoforms, like NHE 6 and NHE9, have also been attributed important roles in tumor pH regulation, carcinogensis, and the development of chemoresistance

[22][23][24][22,23,24]. NHE6 was shown to relocate from the endosomes to the plasma membrane, triggering endosome hyperacidification and chemoresistance in human MDA-MB-231 and HT-1080 cells

[24].

Proton extrusion from cancer cells is further mediated by the monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4, which are upregulated in a variety of tumor types

[25][26][27][28][25,26,27,28]. MCTs transport lactate, but also other metabolites like pyruvate, ketone bodies, or branched-chain ketoacids, in cotransport with H

+ across the plasma membrane

[29][30][31][32][29,30,31,32]. Lactate-coupled proton extrusion from highly glycolytic cancer cells can exacerbate extracellular acidification and contribute to malignant transformation

[33].

Besides the constant extrusion of protons, intracellular pH is regulated by the Na

+/HCO

3− cotransporters NBCe1 and NBCn1. The electroneutral NBCn1 transports Na

+ and HCO

3− in a 1:1 stoichiometry, while the electrogenic NBCe1 operates at a 1 Na

+/2 HCO

3− or 1 Na

+/3 HCO

3− stoichiometry, depending on the phosphorylation state of the transporter

[34][35][36][34,35,36]. Indeed, NBCs have been suggested to be the major acid extruders (HCO

3− importers) in some breast cancer cells

[37][38][37,38]. During cell migration, NBCs contribute to local pH changes by importing HCO

3− at the cell’s leading edge

[13][39][13,39]. In this compartment, NBCs cooperate with the Cl

−/HCO

3− exchanger AE2, which extrudes HCO

3− in exchange for osmotically active Cl

− to support local cell swelling

[13][39][13,39]. The function of the various bicarbonate transporters in tumor acid/base regulation has been extensively discussed in several review articles

[38][40][41][38,40,41].

Tumor pH regulation is further supported by carbonic anhydrases (CAs), which catalyze the reversible hydration of CO

2 to HCO

3− and H

+. Out of the 12 catalytically active CA isoforms expressed in humans, CAIX and CAXII have been attributed a distinct role in tumor pH regulation. In healthy tissue, the expression of CAIX is mainly restricted to the stomach and intestine. In cancer cells, however, the expression of CAIX is often upregulated and correlates with chemoresistance and poor clinical outcome

[42][43][44][42,43,44]. The expression of CAIX is controlled by the hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF-1α), and therefore CAIX is primarily (but not exclusively) found in hypoxic tumor regions. CAIX comprises an exofacial catalytic domain, which is tethered to the plasma membrane with a single transmembrane domain, and an N-terminal proteoglycane-like (PG) domain, which is unique to CAIX amongst the carbonic anhydrases. The PG domain, which is rich in glutamate and aspartate residues, was suggested to function as a proton buffer for the catalytic domain and contributes to the formation of focal adhesion contacts

[45][46][45,46]. In tumor tissue, CAIX functions as a “pH-stat”, which stabilizes the extracellular pH to 6.8

[47]. Like CAIX, CAXII is often upregulated in tumor cells; however, the isoform is, as compared to CAIX, more abundant in healthy cells, too. In contrast to CAIX, expression of CAXII was correlated to both good and bad prognosis, depending on the tumor type

[48][49][48,49]. However, CAXII seems to play a role in the development of multidrug resistance and was therefore suggested as a potential drug target to overcome chemoresistance

[50][51][50,51].

Besides the extracellular CA isoforms IX and XII, different cytosolic CAs, like CAI and CAII, have been attributed a role in various tumor types. However, the function of cytosolic CAs for tumor development and progression has not been studied as extensively as for their exofacial counterparts. For a comprehensive review about the role of the different CA isoforms in tumor cells, see

[52].

2. Acid/Base Transport Metabolons

Intracellular and extracellular carbonic anhydrases interact with acid/base transporters, including NHEs, NBCs, AEs, and MCTs, to form a protein complex coined “transport metabolon”. A transport metabolon was defined as a “temporary, structural-functional, supramolecular complex of sequential metabolic enzymes and cellular structural elements, in which metabolites are passed from one active site to another, without complete equilibration with the bulk cellular fluids (channelling)”

[53][54][55][53,54,55].

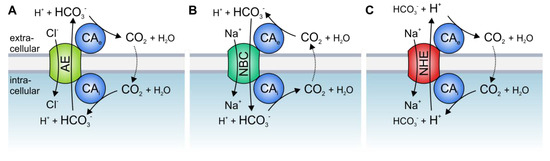

The best studied CA isoform that interacts with acid/base transporters is the intracellular CAII. CAII was shown to bind to an acidic motive (L

886DADD) in the C-terminal tail of the Cl

−/HCO

3− exchanger AE1 (band3)

[56][57][58][56,57,58] (which is also expressed in different types of cancer, including gastric, colonic, and esophageal cancer

[59][60][59,60]). Inhibition of CAII catalytic activity or overexpression of the catalytically inactive mutant CAII-V143Y reduced the transport activity of AE1, expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK-293) cells

[61]. Based on these results, it was suggested that CAII, which is directly bound to the transporter, could locally provide HCO

3− to the exchanger. Thereby, CAII counteracts local depletion of HCO

3− and stabilizes the substrate pool for the transporter (A).

Figure 1. Hypothetical model of the interaction between acid/base transporters and carbonic anhydrases (CAs). Cytosolic CAs bind to the C-terminal tail of various isoforms of (A) Cl−/HCO3− exchangers (AEs), (B) Na+/HCO3− cotransporters (NBCs), and (C) Na+/H+ exchangers (NHEs), while exofacial CAs bind to an extracellular domain of the transporters. By catalyzing the reversible hydration of CO2 to HCO3− and H+ in the direct vicinity of the transporter, CAs provide HCO3− or H+ at the cis side and remove the HCO3− or H+ on the trans side of the transporter.

CAII was also found to bind to, and facilitate the transport activity of, the Na

+/HCO

3− cotransporters NBCe1 and NBCn1

[62][63][64][65][66][62,63,64,65,66], as well as the Na

+/H

+ exchangers NHE1 and NHE3

[67][68][69][67,68,69]. CAII-mediated facilitation of NBC and NHE transport activity requires direct binding of the enzyme to an acidic cluster in the transporters’ C-terminal tail, as well as CAII catalytic activity. In the case of NBC, CAII would either provide or remove HCO

3− to/from the transporter, while in the case NHE, CAII would provide H

+ (B,C).

The activity of HCO

3− transporters is also facilitated by direct and functional interaction with extracellular CA isoforms. CAIV was shown to bind to the fourth extracellular loop of both AE1 and NBCe1

[70][71][70,71]. The binding of CAIV as well as CAIV enzymatic activity is mandatory for the CAIV-mediated increase in HCO

3− transport. Thereby, CAIV would form the extracellular part of the transport metabolon, which provides or removes HCO

3− to/from the transporter to stabilize the HCO

3− gradient for maximum transport function (A,B). In the case of NHE, CAIV would remove protons from the transporter to stabilize the H

+ gradient (C). The transport activity of Cl

−/HCO

3− exchangers is not only facilitated by CAIV but also by CAIX, the catalytic domain of which binds to AE1, AE2, and AE3 to support Cl

−/HCO

3− transport activity

[72][73][72,73]. An overview of the various types of acid/base transport metabolons described so far is given in .

Table 1. Overview of the known interactions between acid/base transporters and carbonic anhydrases. Combinations of CAs and transporters for which an interaction was demonstrated are indicated with ☑. CAs and transporters that have been shown not to interact are indicated with ⊠. Transport metabolons that have been shown in cancer cells are marked in red. For every CA, the left column indicates functional interaction. The right column indicates physical interaction. * CAIV and CAIX interact with MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4 via their chaperons CD (cluster of difference) 147 and GP70.

Even though there is accumulating evidence for the physical and functional interaction between acid/base transporters and CAs, both in vitro and in intact cells, several studies have questioned the existence of bicarbonate transport metabolons, both in respect to the physical as well as functional interaction between CAs and transport proteins

[74][75][76][77][102,103,104,105]. For a comprehensive review on bicarbonate transport metabolons, including the criticism on this concept, we recommend the reviews

[55][78][79][80][55,106,107,108].

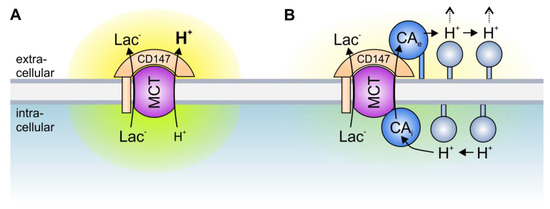

A different type of transport metabolon is formed between intracellular and extracellular CAs and MCTs. In marked contrast to the transport metabolons formed with HCO

3− transporters, the facilitation of MCT activity is independent of CA catalytic activity

[81][82][83][84][86,87,88,99]. In fact, the CAs seem to function as a “proton antenna”, which moves H

+ between the MCT transporter pore and surrounding protonatable residues

[83][88]. Proton-collecting antennae have been described for different H

+-transporters, including cytochrome c oxidase and bacteriorhodopsin

[85][86][109,110]. A proton-collecting antenna is comprised of several acidic glutamate and aspartate residues, which function as “H

+ collectors”, and histidine residues, which function as “H

+ retainers”. The antenna accelerates the protonation rate of functional groups and creates a “proton reservoir” on the protein surface

[87][111]. CAII facilitates the transport activity of MCT1 and MCT4, when heterologously expressed in

Xenopus oocytes

[81][84][86,99]. Pharmacological inhibition of CAII catalytic activity as well as co-expression of the catalytically inactive mutant CAII-V143Y did not suppress CAII-mediated augmentation of MCT transport activity, indicating that the CAII-MCT1/4 metabolon functions independently of the CAII catalytic activity

[81][82][83][84][86,87,88,99]. However, CAII-mediated facilitation of MCT1/4 activity requires direct binding of the enzyme to a cluster of three glutamic acid residues in the transporters’ C-terminal tail

[88][89][89,98]. Interestingly, the transport activity of MCT2, which does not feature a CAII binding site, is not facilitated by co-expression with CAII

[90][97]. However, integration of a CAII binding site into the MCT2 C-terminal tail allows CAII to facilitate MCT2 transport activity when heterologously expressed in

Xenopus oocytes

[89][98]. The binding of CAII to the MCT C-terminal tail is mediated by CAII-His64

[91][92]. Interestingly, His64 forms the central residue of the CAII intramolecular H

+ shuttle, which is crucial for CAII to achieve high catalytic rates

[92][112]. However, CAII-His64 does not participate in H

+ shuttling between the transporter and enzyme

[91][92]. This H

+ shuttle seems to be mediated by the amino acids Glu69 and Asp72, which have been suggested to form a part of the CAII proton-collecting antenna

[91][93][92,113]. Based on these results, it was suggested that CAII, which is directly bound to MCT1/4, facilitates parts of its proton-collecting apparatus to quickly move H

+ between the transporter and the surrounding protonatable residues near the inner face of the cell membrane. Thereby, CAII functions as a proton antenna for the MCT, and counteracts the formation of H

+ nanodomains (local accumulation or depletion of H

+) around the transporter pore, which would impair proton-coupled lactate flux ()

[83][91][94][95][88,92,93,100].

Figure 2. Transport metabolons with monocarboxylate transporters. (A) Due to the slow effective diffusion of protons (most protons are bound to bulky buffer molecules) MCT transport activity leads to the formation of proton nanodomains around the transporter pore. In the case of lactate and H+ efflux, H+ would locally deplete near the intracellular side of the membrane (green cloud) and locally accumulate near the extracellular side (yellow cloud). During lactate and H+ influx, H+ would deplete near the extracellular side and accumulate near the intracellular side of the membrane. These proton nanodomains would in turn decrease MCT transport activity. (B) During lactate and H+ efflux, intracellular CA (CAi), which is bound to the transporter’s C-terminal tail, provides H+ from surrounding protonatable residues to the transporter (thereby functioning as “proton-collecting antenna” for the transporter), while extracellular CA (CAe), which binds to the Ig1 domain of the MCT chaperon CD147, removes H+ from the transporter and shuttles them to surrounding protonatable residues (“proton-distributing antenna”). During lactate and H+ influx, CAe would provide H+ to the transporter, while CAi would remove the H+ from the transporter pore. By this “push and pull” mechanism, intracellular and extracellular CAs counteract the formation of proton nanodomains to allow rapid transport of lactate and H+ across the cell membrane.

MCT transport activity is not only facilitated by intracellular CAII but also by the extracellular isoforms CAIV and CAIX

[96][97][98][99][100][90][90,91,94,95,96,97]. Up to now, the MCT-CAIV transport metabolon has only been investigated in

Xenopus oocytes

[96][98][90][90,94,97], while CAIX was shown to interact with MCTs both in the

Xenopus oocyte expression system and in human breast cancer cell lines

[97][99][100][91,95,96]. As already observed for CAII, the facilitation of MCT transport activity by extracellular CAs is independent of the enzymes’ catalytic activity

[97][90][91,97] but requires close association of the CA to the transporter

[98][100][94,96]. Interestingly, CAIV and CAIX do not directly bind to the transporter but to the first globular (Ig1) domain of the MCT chaperons CD147 (MCT1 and MCT4) and GP70 (MCT2)

[98][90][94,97]. In both carbonic anhydrases, this binding is mediated by a histidine residue that is analogue to His64 in CAII (CAIV-His88 and CAIX-His200)

[97][98][100][91,94,96]. Proton shuttling between MCTs and CAIX seems to be mediated by the CAIX PG domain, which features 18 glutamate and 8 aspartate residues. These acidic residues could function as proton antenna for the protein complex

[100][101][96,114]. The proton antenna in CAIV is yet unidentified. Both CAIV and CAIX have been suggested to function as an extracellular H

+ antenna for MCTs, which shuttles H

+ between the transporter and surrounding protonatable residues, thereby counteracting the formation of extracellular H

+ nanodomains ()

[97][98][100][91,94,96]. Since dissipation of the proton nanodomain on only one side of the membrane could exacerbate the accumulation or depletion of protons on the other side, due to increased MCT transport activity, and intracellular and extracellular CAs have to work in concert for efficient proton handling on both sides of the membrane to allow maximum MCT transport activity ()

[96][94][90,93].

Besides cancer cells, transport metabolons have also been suggested to operate in various cells and tissues, including erythrocytes (AE1-CAII)

[56], kidney (NBCe1-CAII; NHE3-CAII)

[63][68][63,68], gastric mucosal epithelium (AE2-CAIX)

[72], heart muscle (NHE1-CAII; AE3-CAII)

[69][102][69,115], and brain (MCT1-CAII; MCT-CAIV/CAXIV; AE3-CAIV/CAXIV)

[88][103][104][89,116,117].

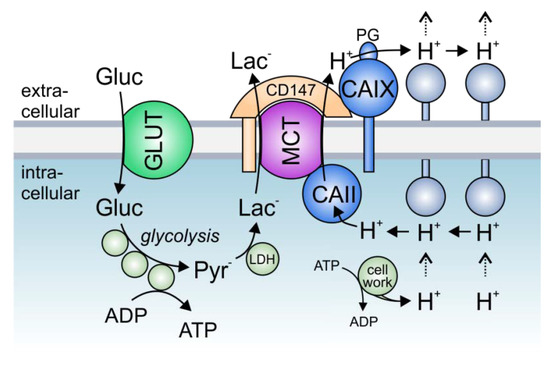

3. The Role of Transport Metabolons in Tumor Metabolism

Solid tumors, which often have to cope with acute local hypoxia, are highly glycolytic tissues, which produce large amounts of lactate and protons

[105][106][118,119]. Proton-coupled lactate extrusion from cancer cells is primarily mediated by the monocarboxylate transporters MCT1 and MCT4

[25][26][27][28][25,26,27,28]. The constant efflux of acid into the pericellular space supports the formation of a hostile tumor microenvironment, in which tumor cells can outcompete their normal host cells

[98][94]. Lactate production is increased under hypoxia, resulting in the need for enhanced lactate export capacity in cancer cells

[97][107][108][91,120,121]. This increase in lactate transport could either be mediated by increased MCT expression levels or by the facilitation of MCT transport function through the formation of a transport metabolon

[97][109][110][91,122,123]. Transport metabolons, formed between MCT1/MCT4 and CAIX, were found in tissue samples of human breast cancer patients but are absent in healthy breast tissue

[100][96]. Interestingly, the number of MCT1/4–CAIX interactions, as shown by an in situ proximity ligation assay (PLA), increased with increasing tumor grade

[100][96]. The increase in glycolysis, as found in higher grade tumors

[111][124], appears to require a higher lactate efflux capacity in cells, which is achieved by an increasing number of transport metabolons

[100][96]. Thereby, CAIX-facilitated H

+/lactate efflux would enable sustained energy production in glycolytic cancer cells to allow continued cell proliferation and tumor progression. Increased glycolysis is often initiated by hypoxia

[106][112][119,125]. In line with this, MCT1/4-CAIX transport metabolons were found in hypoxic MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells but not in normoxic cells

[100][96]. Both breast cancer cell lines show an increase in glycolysis under hypoxia, which is accompanied by an increase in lactate transport capacity

[97][100][91,96]. This hypoxia-induced increase in lactate transport is not mediated by increased expression of monocarboxylate transporters but by the non-catalytic function of CAIX, the expression of which is highly increased in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells under hypoxia

[97][91]. Indeed, both knockdown of CAIX with siRNA, as well as application of an antibody against the CAIX PG domain blocked the hypoxia-induced increase in lactate flux, while inhibition of CA enzymatic activity with 6-ethoxy-2-benzothiazolesulfonamide (EZA) or an antibody directed against the CAIX catalytic domain did not affect lactate transport

[97][99][91,95]. These data let to the conclusion that CAIX, the expression of which is increased under hypoxia, forms a non-catalytic transport metabolon with MCT1 and MCT4 to facilitate H

+-coupled lactate efflux from glycolytic breast cancer cells. The rapid extrusion of lactate and H

+ allows sustained glycolytic activity and cell proliferation (). Indeed, knockout of CAIX as well as the application of an antibody against the CAIX PG domain, but not inhibition of CA enzymatic activity, resulted in a significant reduction in the proliferation of hypoxic MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells

[97][99][91,95]. These data were confirmed in the triple-negative breast cancer cell line UFH-001

[113][101]. Knockdown of CAIX with a CRISPR/Cas9 approach decreased the glycolytic proton efflux rate (GlycoPER), as measured by Seahorse analysis, in pseudo-hypoxic UFH-001 cells treated with the HIF1α-stabilizing agent desferrioxamine (DFO). Yet, isoform-specific inhibition of CAIX catalytic activity with three ureido-substituted benzene sulfonamides (USBs) did not affect proton efflux, indicating that CAIX catalytic activity is not required to facilitate H

+-coupled lactate flux in cancer cells.

Figure 3. The role of lactate transport metabolons in cancer metabolism: Hypoxic tumors meet their energetic demand by glycolysis. Glucose, which is imported into the cell via glucose transporters (GLUTs), is metabolized to pyruvate, which in turn is converted to lactate by the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). Lactate is exported in cotransport with protons (which are produced during metabolic activity) via monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). In hypoxic cancer cells, MCT transport activity is facilitated by the interaction with intracellular CAII and extracellular CAIX, which directly bind to the transporters’ C-terminal tail and the MCT chaperon CD147, respectively. In this protein complex, CAII and CAIX function as a “proton antennae”, which facilitates the rapid exchange of H+ between the transporter pore and surrounding protonatable residues near the cell membrane. Thereby, CAII and CAIX drive the export of H+ and lactate from the cell to allow a high glycolytic rate and support cell proliferation.

Experiments on

Xenopus oocytes and mathematical modeling have shown that efficient lactate shuttling via MCTs requires a carbonic anhydrase on both sides of the plasma membrane

[96][94][90,93]. Even though the intracellular isoform CAII is not cancer specific, it is upregulated in different tumor cells, including breast, lung, colorectal, gastrointestinal, and prostate cancer

[114][115][116][117][126,127,128,129]. PLA assays revealed that CAII is closely colocalized with MCT1 in MCF-7 cells

[91][92]. In these cells, knockdown of CAII resulted in a significant decrease in lactate transport capacity

[91][92]. Even though the expression of CAII is not increased under hypoxia, CAII knockdown had a stronger effect on lactate transport in hypoxic than in normoxic cells. Indeed, the hypoxia-induced increase in lactate transport, which is mediated by CAIX

[97][91], was completely abolished in the absence of CAII. These results indicate that extracellular CAIX requires an intracellular counterpart to facilitate lactate transport from cancer cells. This is in line with previous findings that enhanced proton shuttling by a carbonic anhydrase on only one side of the plasma membrane creates a proton nanodomain on the opposing side, which in turn decelerates proton-coupled lactate flux

[96][94][90,93]. During the efflux of lactate, CAII would collect protons from the intracellular face of the plasma membrane and shuttle them to the transporter pore. On the exofacial side, CAIX would remove the protons from the transporter and shuttle them to surrounding protonatable sites at the membrane. By this “push-and-pull” principle, intracellular CAII and extracellular CAIX would cooperate to ensure efficient efflux of lactate and protons from hypoxic cells to allow sustained glycolytic energy production (). The removal of CA on either side of the membrane would lead to the formation of a proton domain around the MCT on this side and would therefore decrease MCT transport activity, which would lead to cytosolic accumulation of lactate and protons and ultimately to decreased glycolysis and cell proliferation. Indeed, this interpretation is supported by the finding that knockdown of either CAII or CAIX decreased cell proliferation in hypoxic MCF-7 breast cancer cells. For a comprehensive review about MCT transport metabolons in cancer cells, see also

[118][130].