Biochar is a carbon-rich material prepared from the pyrolysis of biomass under various conditions. Recently, biochar drew great attention due to its promising potential in climate change mitigation, soil amendment, and environmental control. Obviously, biochar can be a beneficial soil amendment in several ways including preventing nutrients loss due to leaching, increasing N and P mineralization, and enabling the microbial mediation of N2O and CO2 emissions.

- biochar

- carbon

- nitrogen

- phosphorus

- adsorption

- degradation

- transport

- weathering

1. Introduction

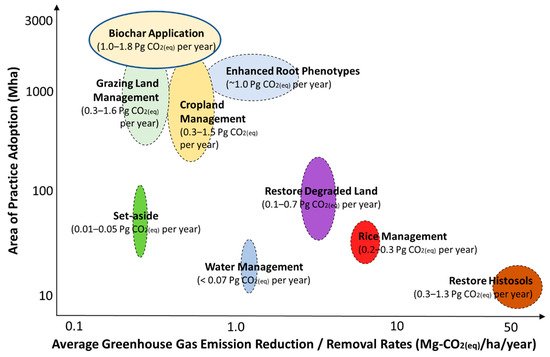

Soil, an important carbon sink that is also the largest terrestrial carbon pool, plays a critical role in regulating the global carbon cycle. Biochar has gained considerable attention in its role in regulating the natural carbon cycle in biogeochemical systems such as soils, as an environmentally friendly adsorbent for CO2. Woolf et al. (2010) estimated that biochar removed 1.0–1.8 Gt CO2–C equivalent of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere annually (Figure 1) [1][2]. Additionally, as a soil amendment, biochar can improve soil fertility [2][3] and crop yields [3][4]. Other benefits of biochar applications can be realized by nutrients management practices [4][5][5,6].

Figure 1. Global potential for agricultural-based greenhouse gas mitigation practices, where biochar application considers a global mitigation potential of 1.0–1.8 Gt CO2–C equivalent per year. Adapted from Paustian et al. (2016) [6][7].

2. Adsorption of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus Species

2.1. Adsorption of Carbon Species

2.1.1. Inorganic Carbons

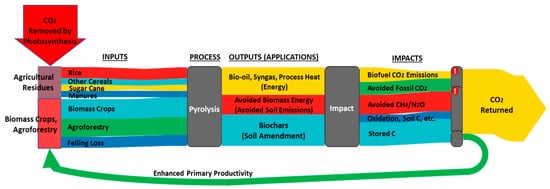

The use of boichar as a soil amendment could improve the CO2 sequestration potential in the agro-ecosystems system. Woolf et al. (2010) found that biochar amendment in soil exhibited a larger mitigation potential (by means of CO2 sequestration) than combustion of the same biomass as bioenergy [1][2] (Figure 2). Soil CO2 sequestration by biochar applications could be mainly attributed to adsorptive and reactive removals of organic and/or inorganic carbons. The mechanisms of adsorptive removal for organic CO2 by biochar include electrostatic force, hydrogen-bonds’ interaction, pore filling, hydrophobic sorption, and π–π (electron donors and acceptors) interaction.

Figure 2. Contribution of sustainable biochar for mitigating global climate change. The results of the analysis indicated that biochar amendment in soil exhibited a larger mitigation potential than combustion of the same biomass as bioenergy, except when fertile soils are amended while coal is the fuel being offset. Adapted from Woolf et al. (2010) [1][2].

2.1.2. Organic Carbons

It is noted that the sorption capacity of organic carbon by biochar is attributed to the partition into the non-carbonized and carbonized (adsorption onto) fraction. In general, biochar amendment in soils exhibited significant additive effects on soil organic carbon over a relatively long period of time. The increase in organic carbon content due to biochar amendment would also provide additional benefits to the soil system, such as a decrease in soil erosion potential [7][77].

2.2. Adsorption of Nitrogen Species

2.2.1. Inorganic Nitrogen

H4+ adsorption was usually attributed to the increase in soil CEC following biochar amendment [8][9][10][11][17,60,98,99]. Most biochar is negatively charged at an ambient pH so that cationic NH4+ can be easily adsorbed via electrostatic attraction. Previous studies reported inconsistent changes in NO3− retention in biochar-amended soils.

2.2.2. Organic Nitrogen

Biochar amendment played an important role in the retention and transport of organic nitrogen species in soils because of strong adsorption behavior. Results indicated that the type of organic amendment and pyrolysis temperature affected nitrate adsorption capacity; furthermore, the increase in surface area and porosity in biochar enhanced nitrate adsorption [12][13][42,45].

2.3. Adsorption of Phosphorus Species

2.3.1. Inorganic Phosphorus

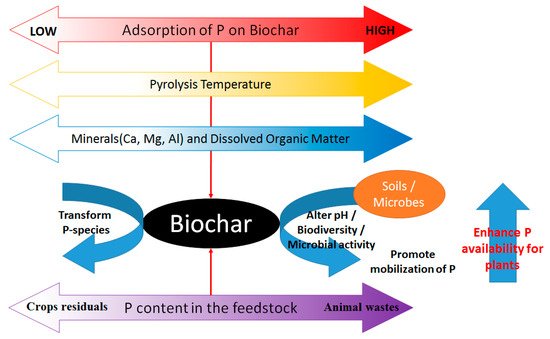

The mineral composition significantly governs phosphorus adsorption on biochar due to possible precipitation and direct phosphorus sorption on the biochar surface. The adsorption of phosphorus species on the biochar surface was an endothermic non-spontaneous process. Biochar prepared at a high temperature (greater than 400 °C) could be used to neutralize soil acidity [14][102]. However, under a low pH condition, biochar-derived dissolved organic matter (DOM) inhibited the adsorption of phosphate [15][103]. Under an acidic environment, biochar adsorption of phosphate took place by surface complex formation [16][104].

2.3.2. Organic Phosphorus

Agro-organophosphorus pesticides, such as chlorpyrifos, fenitrothion, malathion, parathion, and phosphmidon are toxic and can be retained in soils by forming stable complexes with metal oxides [17][121]. The sorption of organophosphorus pesticides by different types of biochar has been studied [18][19][20][21][122,123,124,125]. The presence of biochar impacted the partition of organophosphorus pesticides that controlled the distribution of pesticides in soil, groundwater, and biochar.

3. Biochar Mediated Degradation

3.1. Organic Carbons

Many factors, such as biochar loadings [22][126] and the concentration of labile organic carbon, strongly affected CO2 emissions from soils [23][127]. A number of studies reported that biochar amendment in soils exhibited positive priming effects, i.e., stimulating the turnover of soil organic carbon and thus net CO2 emission [7][77]. However, there were a number of studies that showed negative priming effects on CO2 sequestration [24][25][64,128]. The biodegradation of soil organic matters was decreased when being adsorbed into the porous structure of biochar, a negative priming effect. On the other hand, biochar also enhanced CO2 mineralization in soils [26][129], thereby exhibiting a positive priming effect.

In addition to the adsorptive removal of organic/inorganic carbons, biochar amendment could contribute to reactive removal of carbon species by chemical and/or biochemical (microbial) reactions. It must be mentioned that microbial activities are largely responsible for the decomposition of natural organic matters via a variety of enzymes. Therefore, biochar application in soil could increase soil organic matters and thus stimulate the activity of soil microorganisms. Biochar (as a pyrogenic carbonaceous matter) promotes electron transfer and generates reactive oxygen species to initiate certain bio-chemical reactions. Biochar could also serve as an electron shuttle between organic carbon species and microorganisms in soils, which facilitates biodegradation.

Biochar also influences the biosynthesis of natural organic matters from CO2 in soils.

3.2. Organic Nitrogen Species

Biodegradation of organic N in soils is mainly carried out by N mineralization processes including ammonification and nitrification, in which microorganisms decompose organic N into inorganic forms of NH4+ and NO3−. The reverse process of mineralization, i.e., immobilization, occurs frequently when N-poor organic matter is decomposed. Previous studies showed that biochar can have positive, negative, or negligible effects on N mineralization, depending on feedstock type, soil type, pyrolysis temperature, heating rate, pH, biochar chemical constituents, and microbial activities (Table 13) [27][28][9][29][30][31][10,52,60,136,137,138].

| Feedstock | Pyrolysis Temp. (°C) |

Yield (%) | pH | C (%) | H (%) | O (%) | N (%) | C/N | BET Surface Area (m | 2 | g | −1 | ) | Pore Volume (cm | 3 | g | −1 | ) | Soil Organic Level | Net Mineralization (mg N g-soil | −1 | ) | References |

|---|

| Pine chip | 400 | ‒ | ‒ | 74.4 | 4.06 | 14.6 | 0.25 | 298 | 0.22 | 0.00179 | High soil organic matter | −0.0066 | [29] | [136] | |

| Low soil organic matter | 0.0003 | ||||||||||||||

| 500 | ‒ | ‒ | 81.7 | 3.10 | 8.76 | 0.22 | 371 | 22.77 | 0.0253 | High soil organic matter | −0.0107 | ||||

| Low soil organic matter | −0.0074 | ||||||||||||||

| Poultry litter | 400 | ‒ | ‒ | 41.9 | 2.43 | 16.2 | 4.29 | 10 | 4.85 | 0.0269 | High soil organic matter | 0.032 | |||

| Low soil organic matter | 0.0257 | ||||||||||||||

| 500 | ‒ | ‒ | 44.4 | 1.64 | 12.2 | 4.02 | 11 | 6.55 | 0.0317 | High soil organic matter | 0.0196 | ||||

| Low soil organic matter | 0.0094 | ||||||||||||||

| Wheat straw | 525 | ‒ | 10 | 69.6 | 2.10 | 7.1 | 1.50 | 46 | 0.6 | ‒ | Slow pyrolysis | 0.0028 | [28] | [52] | |

| 525 | ‒ | 6.8 | 49.3 | 3.70 | 24.1 | 1.20 | 41 | 1.6 | ‒ | Fast pyrolysis | −0.0206 | ||||

| Blue mallee wood | 500 | ‒ | 9.6 | 54.9 | ‒ | ‒ | 1.40 | 39.5 | ‒ | ‒ | Dermosol + Phosphorus | −0.0018 | [32] | [114] | |

| Tenosol + Phosphorus | 0.0014 | ||||||||||||||

| Maize | 350 | ‒ | 8.4 | 72.1 | ‒ | ‒ | 1.7 | 43 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 0.00207 | a | [31] | [138] |

| 500 | ‒ | 9.8 | 69.1 | ‒ | ‒ | 1.4 | 49 | ‒ | ‒ | ‒ | 0.00173 | a | [31] | [138] | |

| Maize | 480 | ‒ | 8.6 | 68.1 | 1.5 | ‒ | 0.4 | 164 | ‒ | ‒ | Year 1 | 0.0098 | a | [33] | [139] |

| 480 | ‒ | 8.6 | 68.1 | 1.5 | ‒ | 0.4 | 164 | ‒ | ‒ | Year 2 | 0.00755 | a |

Figure 3 summarizes the factors affecting the adsorption, desorption, and transformation of phosphorus species in biochar-amended soil mixtures.

Figure 3.

The role of biochar in phosphorus cycle.

3.3. Organophosphorus Species

Biodegradation is the major pathway to transform and decompose pesticides in soils. As mentioned above, biochar-amended soils would lower the bioavailability of pesticides. As a result, the biodegradation rate of the organophosphorus pesticide was slower in the presence of biochar than in un-amended soils [34][144].

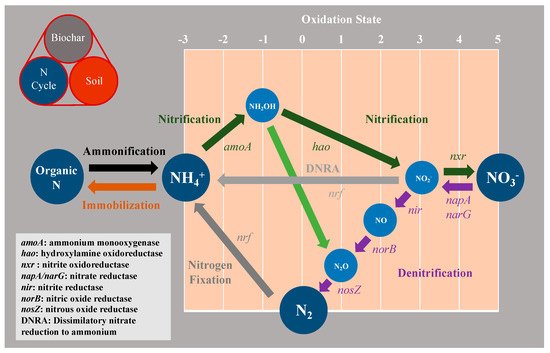

4. Biochar Mediated Transport of Carbon, Nitrogen, and Phosphorus in Soil Systems

Figure 4 illustrates three major process in soil N transport and the transformation cycle including nitrogen fixation, nitrification, and denitrification mediated by biochar. Atmospheric N2 is converted to reactive N, such as NH4+, by functional marker genes of nif in nitrogen fixation (Figure 4), which renders non-reactive N2 bio-available for plants and soil organisms. Biologically mediated nitrogen fixation contributed approximately 17.2 × 107 tons of nitrogen to soils annually [35][150].

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of the nitrogen cycle with associated enzymes. Color-coded arrows indicate the different N transformation processes described in the main text.

Feedstock, pyrolysis temperature, and type of soil and plant cover could alter soil microbiota activity, biomass, and community structure [36][37][38][39][18,145,162,163]. Yang et al. (2018) reported that trampling biocrusts reduced soil microbial biomass C and N, and enzyme activities, in desert ecosystems [40][167]. The declined soil available phosphorus (P), available N, and total N and P may be the major factors that cause the observed reduction in soil microbial. Moreover, the affected bacterial community structure could enhance cycling and mobilization of phosphorus species in biochar-amended soils [39][163]. Likewise, biochar could modify microbial-mediated reactions in the soil phosphorus cycles, such as the mineralization of phosphorus [37][145]. For example, the microbial biomass and phosphorus content increased with an increase in biochar loading to 2% [41][168]. Anderson et al. (2011) found that biochar promoted the growth of phosphorus bacteria and potentially decreased plant pathogens [38][162].

5. Biochar Weathering in Soil Environment

The properties of biochar in soils change substantially in time due to weathering [42][176]. Spokas (2013) studied the weathering of biochar in an agricultural field in Rosemount, MN, for four years and evaluated the effect of natural weathering on net GHG emissions [43][177]. The results indicated that the weathering process increased net CO2 emissions by up to ten-fold, compared with fresh biochars, which reflected the increase in microbial mineralization, probably aided by the chemical oxidation of the biochar during weathering.

6. Outlook

The benefits of biochar as a soil admendment are not always realized due to the limited knowledge regarding the relevant pathways and mechanisms. Future studies should focus on the relationship between biochar amendment and the dissolved organic carbon pool. Additionally, the emergence of advanced green processes for low-carbon biochar production could provide the prospects of developing new alternatives to maximizing the environmental benefits, especially climate change mitigation. The environmental benefits and impacts of biochar production should be critically quantified by life cycle assessments. In addition to environmental beneftis, both social and economic aspects must be considered when developing and employing biochar technologies. To augment the mitigation capacity of biochar-amended soils, long-term field studies with an emphasis on the functional mechanisms responsible for carbon retention and CO2 mitigation in soils are needed.