Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Benedetta Bussolati and Version 2 by Dean Liu.

Angiogenesis is one of the main processes that coordinate the biological events leading to a successful pregnancy, and its imbalance characterizes several pregnancy-related diseases, including preeclampsia. Intracellular interactions via extracellular vesicles (EVs) contribute to pregnancy’s physiology and pathophysiology, and to the fetal–maternal interaction.

- extracellular vesicles

- preeclampsia

- angiogenesis

1. Introduction

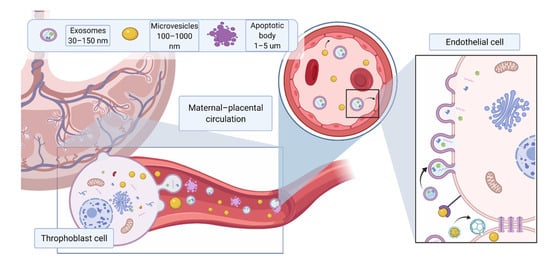

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) have been established as a means of cellular communication and are involved in physiological and pathophysiological processes through the transfer of bioactive molecules such as proteins, RNAs and lipids [1]. EVs are released by all cell types and can be found in all body fluids. The subtype and composition of EVs are dependent on the route of EV generation and parental origin, respectively [2]. The content of EVs can be packaged based on signals received from other cells or environmental factors such as oxygen, glucose concentration and sheath stress. In pregnant women, trophoblast-derived EVs are found in the blood [3], amniotic fluid [4], and urine [5]. These EVs have placenta-specific markers such as HLA-G [6], syncytin-1 [7] and placental-type alkaline phosphatase (PLAP-1) [8]. Due to their small size, EVs can cross the placental barrier, thereby enabling feto–maternal communication throughout the pregnancy [9] (Figure 1). Given that EVs are involved in a wide range of processes, it is no surprise that they play an important role in pregnancy. EVs regulate various normal physiological processes during pregnancy, including implantation of the embryo by regulation of the endometrium, trophoblast invasion, immune regulation of maternal responses and spiral artery remodeling [10]. Changes in the total number, content, and bioactivity of EVs have been reported in pregnancy complications such as preeclampsia (PE) [11].

Figure 1. Different EV subtypes released from the placenta during pregnancy. The main subtypes of extracellular vesicles reported include exosomes (30–150 nm) formed from intracellular endosomal compartments and characterized by expression of tetraspanins (CD63, CD81, CD9); microvesicles (100 nm–1 μm), which originate from cell plasma membrane, characterized by CD 40; apoptotic bodies (>1 μm), which are released by apoptotic cells, express phosphatidylserine on their surface and caspase 3 and 7 internally. Due to their small size, EVs can cross the placental membrane and contribute to feto–maternal signaling. Placental EVs have been previously found in maternal circulation and shown to directly affect maternal endothelium. Created with BioRender.com (accessed on 18 May 2021).

Angiogenesis, the process by which blood vessels form for the delivery of nutrients to the body, is necessary both prior to and during pregnancy. A balance between pro and anti-angiogenic factors during pregnancy is key to a successful pregnancy. Imbalance of angiogenic factors, and subsequently, widespread endothelial dysfunction is considered the hallmark of pregnancy-related diseases such as preeclampsia (PE) [12]. The clinical manifestation of PE includes the development of hypertension after 20 weeks of gestation [13] and the coexistence of either proteinuria or other maternal organ dysfunction such as renal insufficiency, liver dysfunction, neurological features including headache or visual disturbances, hemolysis or thrombocytopenia, pulmonary edema [13][14][15][13,14,15]. Moreover, PE increases the risk of maternal and perinatal mortality and morbidity, and is associated with future cardiovascular disease risk [16]. Preeclampsia is classified as a new onset hypertensive pregnancy disorder. Depending on the time of delivery, early-onset preeclampsia manifests before the 34th week of gestation and is described as a fetal disorder that is associated with placental dysfunction and adverse fetal outcomes. Late-onset preeclampsia requires delivery at or after the 34th week of gestation and is considered as a maternal disorder associated with endothelial dysfunction and end organ damage [13].

Despite great scientific advances, PE is still defined as a “disease of theories”. Insufficient placenta development including abnormal spiral artery remodeling, placental hypoxia, oxidative stress, impaired angiogenesis and insufficient placental perfusion contribute to the development of preeclampsia [17][18][19][17,18,19]. Over the last two decades, increasing evidence suggests that angiogenic factors imbalance plays a pivotal role in PE pathogenesis [20][21][20,21]. Soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), a soluble form of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 1 (VEGFR-1) extracellular ligand-binding domain, is the key anti-angiogenic factor released by placenta during pregnancy. This soluble form of VEGFR-1 can bind to all isoforms of VEGF [22][23][22,23], as well as to the PlGF. Indeed, sFlt- 1 may act as a decoy receptor and hinder VEGF signaling through binding to its cognate receptors, thus inhibiting VEGF-mediated pro-angiogenic effects [24]. During normal pregnancy, the levels of sFlt-1 increase throughout gestation, providing a limiting and protective barrier for potentially unhealthy VEGF-dependent over signaling [25][26][25,26]. However, maternal circulating sFlt-1 levels are significantly increased in PE compared to normal pregnancy prior to the onset of the disease [27]. Furthermore, in vivo studies have showed that exogenous administration of sFlt-1 led to typical PE-like symptoms such as hypertension and glomerular endotheliosis in pregnant rats [20], whereas reduced circulating levels of free sFlt-1 below critical threshold rescued the damaging effects of sFlt-1 [21][28][29][30][21,28,29,30]. Another anti-angiogenic factor released by placenta is soluble endoglin (sEng), a soluble form of the coreceptor of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), which acts as a decoy receptor of TGF-β leading to a decrease in angiogenesis [31]. Not surprisingly, harmful molecules released from the placenta may reach the fetal circulation, causing endothelial dysfunction in the fetus. Indeed, many reports [32][33][32,33] have described fetoplacental endothelial dysfunction associated with preeclamptic pregnancies (Figure 1). A vicious cycle is therefore created, which is to the detriment of the mother and the fetus.

2. Pro-Angiogenic Functions of EVs in Healthy Pregnancy

The influence of EVs on the angiogenic process has been reported in various in vitro and in vivo studies [12]. EVs are considered to modulate the angiogenic process through the transfer of several molecules including small RNA species and proteins. In particular, small RNA species, such as microRNA, are transferred by EVs and are considered pivotal for the reprogramming of target cells [34][35]. Lombardo et al. reported that miRNA-126 and p-STAT5 in endothelial-derived EVs are responsible for IL-3-mediated paracrine pro-angiogenic signals [35][36]. Similarly, endothelial-derived exosomes require miRNA-214 to simulate angiogenesis in recipient cells [36][37]. In vivo, injection of EPC-derived EVs containing the angiogenic miRNAs miRNA-126 and miRNA-296 in a mouse hind limb ligation model significantly increased capillary density and blood perfusion [37][38]. Several other microRNAs present in the EV cargo have been reported to be involved in the induction of angiogenesis, including miRNA-125a [38][39], miR31 [39][40] and miRNA-150 [40][41]. In parallel, several proteins released by EVs have also been found to be involved in the modulation of angiogenesis, including VEGF [41][42][42,43], FGF-2 [43][44], PDGF [42][44][45][43,45,46], c-kit [46][47], sphingosine-1-phosphate [47][48], regulated on activation of normal T cell expression and secretion [47][48], CD40L [48][49], C-reactive protein [49][50][51][50,51,52], metalloproteases [48][52][49,53], stem cell factor [53][54], and urokinase-type plasminogen activator. Furthermore, EVs can promote angiogenesis through the transfer of key lipids and proteins involved in activation of PI3K [54][55], extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 [55][56][57][56,57,58], Wnt4/βcatenin [58][59], and nuclear factor-κB [59][60][60,61] pathways. In pregnancy, a large number of studies focus on the activity of EVs released by maternal and fetal cells, including endothelial cells, immune cells, trophoblast and stem cells with the latter being present in the umbilical cord, placenta, amniotic fluid and amniotic membranes (Figure 1). These EVs are capable of inducing tissue regeneration and angiogenesis and can be found in maternal circulation starting from 7 weeks of gestation [61][62], in amniotic fluid [4], and urine [5]. The heterogeneity of EVs produced in this environment results in a plethora of pro-angiogenic factors being delivered to support the physiological development of normal pregnancy and the maintenance of endothelial homeostasis (Table 1). The following paragraphs will discuss the role of healthy pregnancy-related EVs in angiogenesis, according to their different tissue types of origin.Table 1. Angiogenic factors associated with EVs and their role in pregnancy.

| Source | Bio-Factor/Functional Assay | Platform | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Umbilical cord blood | miRNA-15, miRNA-150 | In vitro | Luo et al., 2018 [44][45] |

| Umbilical cord | VEGF, VEGFR-2, MPC-1, angiogenin, tie-2/TEK and IGF | In vitro | (Xiong et al., 2018) [62][64] |

| Umbilical cord | Activation of Wnt/β-catenin pathway | In vitro | (Zhang et al., 2015) [58][59] |

| Placental explant EVs | Angiogenesis and migration | In vitro and in vivo | (Salomon et al., 2013) [63][34] |

| Trophoblast-EVs | EMMPRIN | In vitro and in vivo | (Balbi et al., 2019) [64][69] |

| Maternal–blood EVs | Shh | In vivo | (Martínez et al., 2006) [65][73] |

| Maternal–blood EVs | enhances endothelial cell proliferation, migration, and tube formation | In vitro | (Jia et al., 2018) [66][63] |

| Throphoblast-EVs | eNOS | In vitro | (Motta-Mejia et al., 2017) [67][66] |

| Placental explants | Flt/endoglin | In vitro | (D. Tannetta et al., 2014) [61][62] |

3. Anti-Angiogenic Actions of EVs in Preeclampsia

As discussed above, placental-derived EVs play an important physiological role in mother and fetus communication through the delivery of a range of proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [68][74]. On the other hand, alterations in the concentration and content of placenta-derived EVs are associated with pregnancy-related diseases, such as PE [69][70][71][72][73][75,76,77,78,79]. Angiogenic imbalance is considered to be the main contributor of endothelial dysfunction, in PE [74][80]. Flt-1 and Eng have been detected on the surface of placental-derived EVs [3][69][75][3,75,81]. These Flt-1 and Eng expressing EVs are capable of binding to pro-angiogenic factors, VEGF, PlGF and TGF-β [69][75]. Interestingly, the capacity of Eng expressing placental-EVs to bind TGF-β was much higher in comparison to the affinity for VEGF and PlGF to Flt-1 expressing EVs [70][76].

The anti-angiogenic effect of circulating EVs in PE appears to be, at least in part, mediated by the presence of Flt-1 or Eng in the form of membrane receptors on the EV surface, as these can act as decoy receptors by sequestering angiogenic soluble factors, similarly to the presence of the soluble forms. Tannetta et al. [76][82] showed that EVs isolated from preeclamptic placenta expressed higher level of Flt-1 in comparison to EVs isolated from normal placenta. Application of EVs containing sFlt-1 to HUVEC cells led to a reduction in tube formation, cell invasion and an increase in cellular permeability [76][82]. EVs isolated from first trimester placental explants treated with sera from either normal pregnant women or preeclamptic women showed no significant differences in their size or concentration. However, EVs isolated from preeclamptic sera-treated placental explants were able to cause endothelial cell activation due to up-regulation of High Mobility Group Box 1 (HMGB1) in EVs, a potent danger-associated molecular pattern/danger signal that can lead to sterile inflammation [77][83]. Furthermore, administration of platelet or endothelial cell-derived EVs to pregnant mice induced PE-like symptoms and decreased embryonic vascularization [78][84]. Han et al. showed that infusion of EVs derived from injured placenta rather than normal placenta led to the development of hypertension and proteinuria in pregnant mice. These EVs released from injured placenta caused disruption of endothelial integrity and enhanced vasoconstriction [79][85]. These studies highlighted a possible pathogenic role of circulating EVs in PE. Studies in vivo have also confirmed the role of EVs in affecting angiogenesis and inducing PE-like syndromes by administering EVs derived from pre-eclamptic placentas in mice. The injection of those EVs resulted in damage to the vasculature and poor fetal nutrition [75][81].

The shedding of EVs into the maternal blood in PE has also been shown to correlate with systolic blood pressure [80][86]. Neprilysin (NEP), a membrane-bound metalloproteinase that is involved in vasodilator degradation, has been directly correlated with hypertension (REF). Interestingly, NEP has been found on the surface of trophoblast-EVs. Moreover, Gill et al. [81][87] showed that the level of NEP in the EVs derived from placenta and syncytiotrophoblast cells were both augmented in preeclamptic women compared to normal pregnant women, indicating that increased levels of NEP-expressing EVs in the maternal circulation may play a role in causing PE-related symptoms including hypertension, heart failure [81][87]. Furthermore, placental trophoblast-EVs in PE contain reduced levels of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), and thus reduced production of nitric oxide production, a potent vasodilator (59), suggesting that PE-associated EVs may contribute to decreased NO bioavailability, resulting in endothelial dysfunction. Additionally, EVs may also inhibit angiogenesis by low-density lipoprotein receptor-mediated endocytosis [82][88], and by CD36-dependent uptake of EVs and induction of oxidative stress [83][84][89,90].

Not surprisingly, the majority of studies that have investigated EV in the development of PE have focused on the effect of placental EVs on the endothelium. Vascular smooth muscle cells residing in vessels are also an important part of the processes that lead to placentation and vascular remodeling. EVs from extravillous trophoblasts were reported to promote vascular smooth muscle cell migration, thus suggesting their role in the remodeling of spiral arteries [85][91]. However, the possible contribution of EVs on vascular smooth muscle cells in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia have not yet been researched.

Beside membrane-bound proteins, EVs derived from gestational tissues during complicated pregnancies contain multiple miRNAs, which may play an anti-angiogenic role under these conditions, particularly in PE [33]. Cronqvist et al. [86][92] demonstrated that syncytiotrophoblast-derived EVs directly transferred functional placental miRNA that directly targeted Flt-1 mRNA to primary human endothelial cells and subsequently regulated the expression of Flt-1, suggesting that miRNA enclosed in placental EVs may directly affect the maternal and fetal endothelial function through regulating angiogenic factors [86][92]. The miRNAs most commonly involved in angiogenic processes are outlined below (Table 2) [11]. For example, miRNA-210, which has an anti-angiogenesis property is actively secreted in placental-EVs. It has been found in the circulation of pregnant women and the level of miRNA-210 was elevated in women with PE and hypoxia [87][93]. In addition, EVs derived from trophoblast and endothelial cells contained miRNA-210 and its action may be mediated through directly targeting ERK [42][43]. miRNA-520c-3p, another miRNA found in trophoblast-EVs, can reduce invasiveness in cancerous cells [88][89][94,95]. Interestingly, Takahashi et al. [89][95] showed that MiRNA-520c-3p was present in first-trimester trophoblast cells and trophoblast cell lines and that overexpression of MiRNA-520c-3p in EVs significantly inhibited cell invasion by targeting CD44. The results showed that EVs produced by cells with miRNA-520c-3p overexpression significantly reduced invasiveness via repression of CD44. Moreover, several miRNAs which have been previously associated with hypertension have been found to be differentially expressed in preeclamptic EVs, including miRN26b-5p, miRNA-7-5p and miR181a-5p [90][96]. In addition, placental 19 miRNA cluster (C19MC), a cluster almost exclusively expressed on the placenta [91][97], has been reported to be altered in PE [88][94].

Table 2. Angiogenic factors associated with EVs and their role in pregnancy.

| Source of EVs | Bio-Factor/Functional Assay | Platform | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placental explants/trophoblast cell culture/maternal blood | s-Eng | in vitro and in vivo | (Chang et al., 2018) [92][100] |

| (Schuster et al., 2020) [74][80] | |||

| (D. S. Tannetta et al., 2013) [70][76] | |||

| (Salomon et al., 2014) [3] | |||

| Placental explants/trophoblast cell culture/maternal blood | s-Flt | in vitro and in vivo | (Chang et al., 2018) [75][81] |

| (Schuster et al., 2020) [74][80] | |||

| (D. S. Tannetta et al., 2013) [69][75] | |||

| (Salomon et al., 2014) [3] | |||

| Trophoblast EVs | NEP | In vitro | (Gill et al., 2019) [81][87] |

| Placental explants | VEGFR1/Endoglin | in vivo | (Tannetta et al. 2013) [76][82] |

| Placental explants | HMGB1 | In vitro | (Xiao et al.,2017) [77][83] |

| Placental explant | miRNA-210 | In vitro | (Anton et al., 2013) [87][93] |

| Placental explant | miRN26b-5p, miRNA-7-5p and miR181a-5p | In vitro | (Zhang et al., 2020) [90][96] |

| Placental explant | C19MC associated miRNA | In vitro | (Morelli et al., 2012) [88][94] |

| Maternal circulation | miRNA-486-1-5p, miRNA-486-2-5p | In vitro | (Salomon et al., 2013) [63][34] |

| Trophoblast EVs | miRNA-520c-3p | In vitro | (Takahashi et al., 2017) [89][95] |

| Serum derived EVs | Syncitin-2 | X | (Vargas et al., 2014) [7] |

Altogether, the studies described above suggest that EVs derived from preeclamptic placentas play a direct role in endothelial dysfunction and contribute to PE development through their membrane-bound proteins and the release of internal molecules such as anti-angiogenic proteins and miRNAs. However, recent studies have challenged these theories. It has been shown that EVs isolated using the common methods may cause contamination of soluble bioactive factors that may affect their resultant bioactivities [93][98]. O’Brien et al. [94][99] showed that placental explant-derived EVs had no significant effect on angiogenesis in vitro when EVs were administered alone, in contrast with the effect of EVs administered with conditioned medium. These data may suggest that the endothelial dysfunction associated with PE is linked with the action of soluble factors rather than EVs. To fully elucidate this point, future research on EVs bioactivity requires more stringent design and planning. Moreover, EVs from different sources must be researched on different platforms (in vitro, in vivo, organ on a chip) and on different functional assays (invasion, angiogenesis, apoptosis, etc.).

(References would be added automatically after the entry is online)