Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Catherine Yang and Version 1 by Roghayeh Shahbazi.

Fermented plant foods are gaining wide interest worldwide as healthy foods due to their unique sensory features and their health-promoting potentials, such as antiobesity, antidiabetic, antihypertensive, and anticarcinogenic activities.

- fermented plant foods

- fermented blueberries

1. Introduction

The anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties of plant-based fermented foods are well documented [40,41,42][1][2][3]. The functional properties of fermented products are, in part, related to the probiotics content of the products [29][4]. Numerous health-promoting benefits have been attributed to probiotics due to their anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities at the gut level and beyond [4,43,44,45,46][5][6][7][8][9]. Probiotic consumption in the form of fermented foods can improve gut barrier integrity and gut immunity and maintain gut homeostasis [4,29,47][5][4][10], through different mechanisms, including the inhibition of pathogen colonization, the induction of antimicrobial peptides production and mucus secretion, the increase of IgA production, the down-regulation of the Th17 and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17F, IL-23, and the upregulation of Tregs production [48,49,50,51][11][12][13][14].

Moreover, fermentation will lead to the degradation of complex phytochemical molecules into smaller bioactive polyphenols. Studies have shown that polyphenolic compounds found in fermented products are beneficial in microbiota metabolism and growth [52][15] and can inhibit the production of inflammatory cytokines and suppress inflammatory responses [53][16]. Furthermore, neutralizing free radicals, regulating antioxidant enzyme activities, reducing oxidative stress, and enhancing immune system activity are other potential mechanisms by which plant-based fermented foods and beverages exert health benefits [54,55][17][18].

2. Fermented Berries

Berry fruits are well known for their significant health benefits [58,59][19][20]. Various berries have been shown to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activities [60[21][22],61], reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases [58][19], neurodegenerative disease [62][23], diabetes mellitus [63][24], and protect against cancer [64][25]. Berries are a good source of various micronutrients and bioactive compounds with antioxidant properties, including vitamins C and E, selenium, carotenoids, and most importantly, phytochemicals such as anthocyanin and tannins [58,59,61,65][19][20][22][26]. The bioavailability of berry polyphenols is low [58[19][26],65], therefore, it has been suggested that the functional properties of the polyphenolic components of berries are related to their metabolites produced over colonic fermentation by gut microorganism [61,65][22][26]. Interestingly, berry polyphenols and their metabolites affect gut microbial composition by increasing the frequency of beneficial genera, including Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia [61][22]. Moreover, berry metabolites have been shown to suppress inflammatory cytokines and mitigate gut inflammation [61][22].

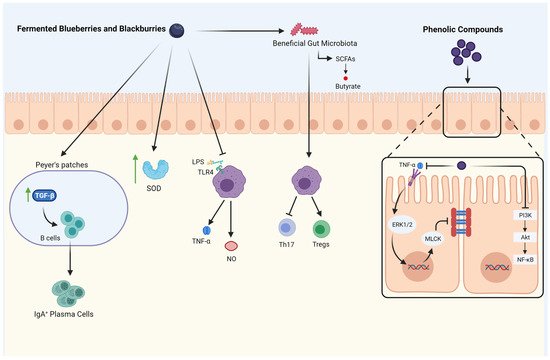

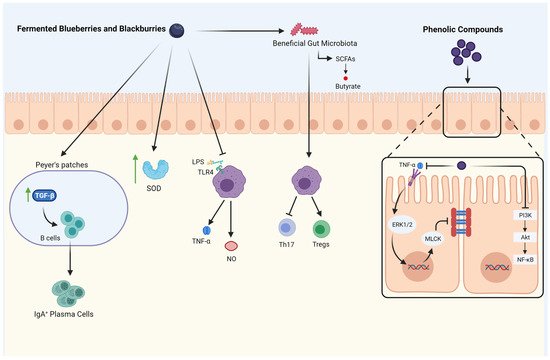

Fermentation may increase the positive effects of berries due to an increase in polyphenols and the antioxidant capacity of fermented products [66][27]. Figure 1 illustrates the anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory activity of fermented berries.

Figure 1. The Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory activity of fermented berries. ↑: increase; TGF-β: transforming growth factor-beta; IgA: immunoglobulin A; SOD: su-peroxide dismutase; LPS: Lipopolysaccharide; TLR4: Toll-like receptor-4; TNF-α: tumor necrosis factor; NO: nitric oxide; SCFAs: short-chain fatty acids; Th17: T helper 17; Tregs: regulatory T cells; PI3K: phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase; AKT: protein kinase B; NF-κB: nu-clear factor-kappa B; MLCK: myosin light-chain kinase; ERK: signal-regulated kinase.

Fermented blueberries and blackberries modulate the gut microbiota populations by increasing beneficial bacteria. Moreover, they improve the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) and enhance mucosal immunity by promoting secretory IgA (sIgA) cells through increasing TGF-β activity. Fermented blueberries and blackberries also induce antioxidant enzymes like superoxidase dismutase (SOD), which increase the radical scavenging capacity. Furthermore, the inflammatory responses are inhibited by inhibiting macrophage pro-inflammatory mediators release (nitric oxide, TNF-α). It also influences immune cells by inhibiting Th17 activity and the differentiation of Tregs. The phenolic compounds released by the digestion of blackberries and blueberries inhibit PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway and improve the gut barrier. Moreover, phenolic compounds decrease gut permeability by inhibiting TNF-α and its downstream, including ERK1/2 and MLCK. Created with Biorender.com (accessed on 29 April 2021).

2.1. Fermented Blueberries

Blueberries are among the richest sources of phenolic compounds, such as anthocyanins, flavonols, and proanthocyanidins which possess high antioxidant capacity [67,68][28][29]. Because of the high content of phenolic compounds, blueberries are known to have valuable health effects [67,69,70,71][28][30][31][32]. Biotransformation of blueberries during the fermentation process increases their phenolic compounds content and bioavailability, as well as antioxidant activity [72,73][33][34]. Numerous in vitro and animal studies have shown significant anti-inflammatory properties of fermented blueberries through counteracting reactive oxygen species (ROS), suppressing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and inhibiting inflammatory signaling pathways [72][33] and, therefore, exerting a protective function against chronic inflammatory disorders such as obesity [74][35], diabetes [63[24][35],74], neurodegenerative diseases [75][36], and cancer [72][33].

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is the main outer layer component of Gram-negative bacteria which can stimulate the innate immune system and inflammation by activation of the Toll-like receptor-4 (TLR4)/NF-κB signaling pathway [76][37]. LPS-stimulated macrophages are one of the best models for studying the anti-inflammatory potential of different phytochemicals in foods [77][38]. Macrophages are the most important immune cells that contribute to the initiation of inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines such as nitric oxide (NO) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF-α) [78][39]. Overproduction of NO by inducible NO synthase (iNOS) contributes to developing inflammatory conditions [62,79,80][23][40][41]. Fermented blueberry and cranberry juices (fermented with bacterium Serratia vaccinii, isolated from blueberry microflora) have been reported to suppress NO production activated by LPS/interferon-gamma (INF-γ) in mouse macrophage [62][23]. Also, fermented polyphenol-enriched blueberry preparation (PEBP) could inhibit breast cancer cell line growth and breast cancer stem cells development. In vivo, PEBP inhibited tumor development, the formation of ex vivo mammospheres, and lung metastasis. PEBP exerted its anticarcinogenic effects through regulating the activity of transcription factors as well as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (AKT), MAPK/extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and STAT3 pathways [72][33].

Fermented blueberries may counteract obesity and diabetes, at least partly, through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities [74][35]. The administration of fermented blueberry juice reduced hyperglycemia in diabetic mice and inhibited the development of obesity, glucose intolerance, and diabetes in pre-diabetic KKAy mice. Fermented blueberry juice displayed its antiobesity and antidiabetic role by mitigating oxidative stress and increasing adiponectin levels [74][35]. Adiponectin decreases tissue triglyceride content and insulin resistance [81][42]. Adiponectin gene expression is inhibited by ROS [74][35] and pro-inflammatory cytokines [74,82][35][43].

Fermented blueberries may prevent neurodegenerative disease through anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activity [75][36]. ROS-induced oxidative stress causes neuronal cell damage. In neuronal cell culture, fermented blueberries with Serratia vaccinii induced antioxidant enzymes activities and prevented neuronal cell death through the upregulation of cell survival signaling pathways such as MAPK family enzymes p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and the downregulation of cell death pathways such as ERK1/2 and MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK1/2) [75][36]. Furthermore, the antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of fermented blueberries with Lactobacillus plantarum (L. plantarum) has been found in human cervical carcinoma HeLa cells [83][44].

Evidence has shown the health benefits of fermented blueberries may be to some extent attributable to gut microbiota modulation [84,85][45][46]. In an in vitro model, fermentation of blueberry pomace with Lactobacillus casei (L. casei) increased its antioxidant activity by a significant increase in superoxide dismutase activity and radical scavenging capacity. Fermented blueberry pomace also improved gut function by altering fecal microbial composition through inhibiting Escherichia coli, Enterococcus, and increasing the abundance of beneficial microbiota such as Bifidobacterium, Ruminococcus, Lactobacillus, Akkermansia genera, and butyrate-producing bacteria, and increasing the short-chain fatty acid (SCFAs) production [84][45]. In the in vivo model, the effect of supplementation of mice receiving a high-fat diet with L. casei-fermented blueberry pomace was assayed on gut immunity and microbiota [85][46]. Fermented blueberry supplementation improved mucosal immunity by promoting secretory IgA (sIgA) secretion and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) levels in the intestine. TGF-β is an intestinal mucosal immunity modulator and a key mediator in stimulating the IgA+ B cells production in Peyer’s patches of the intestine. A high-fat diet is associated with a decrease in TGF-β level [85,86][46][47]. Besides, fermented blueberries altered the gut microbiota’s composition and frequency toward an increase in Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus, and Akkermansia bacteria and a decrease in Firmicutes phyla [85][46]. Fermented blueberries also increased the production of SCFAs. Therefore, fermented blueberries increased sIgA level by improving gut microbiota and SCFAs production [85][46]. Moreover, this product has been shown to counteract intestinal inflammation by the reduction of TNF-α and myeloperoxidase and inducing interleukin (IL-10) production and improved gut barrier function and immunity by regulating NF-κB/myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) signaling [87][48] and the overexpression of MLCK results in gut barrier permeability and dysfunction [87,88][48][49].

The antihypertensive activity of fermented blueberries through gut microbiota modulation has been studied in rats [89,90][50][51]. In a study in rats, intake of freeze-dried fermented blueberries with L. plantarum DSM 15,313 significantly decreased blood pressure in healthy rats and rats with L-NAME induced hypertension, while a change in gut cecal microbiome was observed in healthy rats [89][50]. In a similar study, no significant effects were observed on blood pressure and cecal microbial community diversity following feeding hypertensive rats with L. plantarum fermented blueberries [90][51].

Zhong et al. (2020) investigated the effect of blueberry products on metabolic syndrome by regulating the gut microbial population [91][52]. They supplemented high-fat-fed mice with fresh blueberry juice or fermented blueberry juice. Both juices could reduce fat accumulation, hyperlipidemia, and insulin resistance in mice. A high level of SCFAs production was observed in both groups; SCFAs may reduce insulin resistance by suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokine production [91][52]. Furthermore, fresh and fermented juices enhanced the diversity and richness of the gut microbial population. Interestingly, the fermented blueberry group demonstrated a low frequency of some obesity-related genera such as Oscillibacter and Alistipes belonging to the Firmicutes phyla and a high frequency of leanness-related genera such as Akkermansia, Barnesiella, Olsenella, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus. Therefore, blueberry products could reduce metabolic syndrome symptoms, partly by modulating gut microbiota [91][52]. In a study in a polygenic mouse model of obesity, supplementation with blueberry changed gut microbiota composition towards a substantial rise in the population of Bacteroidetes and Actinobacteria and improved the obesity-related metabolic outcomes [92][53].

2.2. Fermented Blackberries

Blackberry is known for its high content of antioxidant compounds, particularly anthocyanins, ellagitannins, gallic acid, and significant antioxidant capacity based on its high oxygen radical absorbance capacity [93,94][54][55]. Preclinical and clinical studies have shown a protective effect of this fruit against chronic diseases by inhibiting oxidative stress and inflammation [93][54]. As aforementioned, the fermentation process leads to an increase in the berries’ phenolic content [67[28][56][57],95,96], so fermented blackberry juice may exert more health benefits compared to non-fermented juice [97][58].

Some studies have shown the anti-inflammatory potential of anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins from fermented blueberry–blackberry beverages through NF-κB signaling inhibition [66][27]. Adipose tissue hyperplasia during obesity induces the secretion of adipocytokines such as leptin, interleukin-6 (IL-6), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-10, TNF-α, monocyte chemo-attractant protein-1, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1, which are responsible for obesity-related inflammation [98][59]. Some of the released adipokines induce the infiltration of inflammatory macrophages into the adipose tissue and exacerbate the inflammatory responses [99][60]. An in vitro adipose tissue inflammatory model revealed the potential role of enriched anthocyanin fractions from blueberry-blackberry fermented beverages in the inhibition of inflammatory responses related to obesity through reducing the secretion of NO, TNF-α, and inhibition of NF-κB activation in LPS-induced mouse macrophage. Those fractions also reduced intracellular fat accumulation in adipocytes and increased insulin-induced glucose uptake in adipocytes [100][61].

Oxidative stress contributes to the photoaging process. The high expression of iNOS and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) in photoaged skin has been reported [101,102][62][63]. UVB induces ROS production, and ROS induces the expression of iNOS and COX-2, leading to inflammatory responses and skin damage [103][64]. Besides, UVB activates the NF-κB pathway, which is a pivotal mediator of the immuno-inflammatory reactions occurring in the pathogenesis of different dermatologic disorders [104,105][65][66]. Kim et al. (2019) showed the protective effect of fermented blackberry against ultraviolet B (UVB)-induced skin photoaging. They found that fermentation of blackberry with L. plantarum increased the antioxidant capacity of the fruit, inhibited activation of NF-κB signaling, and reduced the production of iNOS and COX-2 [103][64].

Although we could not find published research investigating the fermented blackberry products’ influence on the gut microbial composition, the beneficial impact of non-fermented blackberry and its compounds on gut microbiota and the mitigation of inflammatory conditions related to gut microbial dysbiosis has been investigated [106][67]. For example, blackberry anthocyanin-rich extract can restore high-fat diet-induced gut microbiota dysbiosis in Wistar rats. This extract can recover gut microbial diversity and protect against dysbiosis-induced neuroinflammation [106][67]. Further, a mixture of blackberry fruit and leaf extracts effectively prevented diet-induced non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Sprague–Dawley rats [107][68]. Feeding rats with the mixture resulted in an elevation in antioxidant enzyme capacity, mitigation of inflammatory responses, modulation of gut microbiota by increasing the frequency of Lactobacillus and Akkermansia in the fecal samples, enhancement of the gut integrity, and increase in the frequency of mucus-secreting goblet cells [107][68].

References

- Zhao, J.; Gong, L.; Wu, L.; She, S.; Liao, Y.; Zheng, H.; Zhao, Z.; Liu, G.; Yan, S. Immunomodulatory effects of fermented fig (Ficus carica L.) fruit extracts on cyclophosphamide-treated mice. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 75, 104219.

- Birhanu, B.T.; Kim, J.-Y.; Hossain, M.A.; Choi, J.-W.; Lee, S.-P.; Park, S.-C. An in vivo immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory study of fermented Dendropanax morbifera Léveille leaf extract. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2018, 18, 222.

- Zulkawi, N.; Ng, K.H.; Zamberi, R.; Yeap, S.K.; Satharasinghe, D.; Jaganath, I.B.; Jamaluddin, A.B.; Tan, S.W.; Ho, W.Y.; Alitheen, N.B.; et al. In vitro characterization and in vivo toxicity, antioxidant and immunomodulatory effect of fermented foods; Xeniji™. BMC Complementary Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 344.

- Bell, V.; Ferrão, J.; Pimentel, L.; Pintado, M.; Fernandes, T. One Health, Fermented Foods, and Gut Microbiota. Foods 2018, 7, 195.

- Shahbazi, R.; Yasavoli-Sharahi, H.; Alsadi, N.; Ismail, N.; Matar, C. Probiotics in Treatment of Viral Respiratory Infections and Neuroinflammatory Disorders. Molecules 2020, 25, 4891.

- Forsythe, P. Probiotics and lung immune responses. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2014, 11 (Suppl. 1), S33–S37.

- Mortaz, E.; Adcock, I.M.; Folkerts, G.; Barnes, P.J.; Paul Vos, A.; Garssen, J. Probiotics in the management of lung diseases. Mediat. Inflamm 2013, 2013, 751068.

- Westfall, S.; Lomis, N.; Kahouli, I.; Dia, S.Y.; Singh, S.P.; Prakash, S. Microbiome, probiotics and neurodegenerative diseases: Deciphering the gut brain axis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. CMLS 2017, 74, 3769–3787.

- Lavasani, S.; Dzhambazov, B.; Nouri, M.; Fåk, F.; Buske, S.; Molin, G.; Thorlacius, H.; Alenfall, J.; Jeppsson, B.; Weström, B. A novel probiotic mixture exerts a therapeutic effect on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis mediated by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9009.

- Feng, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, P.; Song, H.; Wang, F. Antibiotics induced intestinal tight junction barrier dysfunction is associated with microbiota dysbiosis, activated NLRP3 inflammasome and autophagy. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0218384.

- Zhang, S.; Chen, D.C. Facing a new challenge: The adverse effects of antibiotics on gut microbiota and host immunity. Chin. Med. J. 2019, 132, 1135–1138.

- Yahfoufi, N.; Mallet, J.; Graham, E.; Matar, C. Role of probiotics and prebiotics in immunomodulation. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2018, 20, 82–91.

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Plaza-Díaz, J.; Muñoz-Quezada, S.; Gómez-Llorente, C.; Gil, A. Probiotic mechanisms of action. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 61, 160–174.

- Wang, K.; Dong, H.; Qi, Y.; Pei, Z.; Yi, S.; Yang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Meng, F.; Yu, S.; Zhou, T.; et al. Lactobacillus casei regulates differentiation of Th17/Treg cells to reduce intestinal inflammation in mice. Can. J. Vet. Res. Rev. Can. Rech. Vet. 2017, 81, 122–128.

- Selhub, E.M.; Logan, A.C.; Bested, A.C. Fermented foods, microbiota, and mental health: Ancient practice meets nutritional psychiatry. J. Physiol. Anthropol. 2014, 33, 2.

- Feng, Y.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Gao, Z. Recent research process of fermented plant extract: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 40–48.

- Kim, B.; Hong, V.M.; Yang, J.; Hyun, H.; Im, J.J.; Hwang, J.; Yoon, S.; Kim, J.E. A Review of Fermented Foods with Beneficial Effects on Brain and Cognitive Function. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2016, 21, 297–309.

- Aruoma, O.I.; Somanah, J.; Bourdon, E.; Rondeau, P.; Bahorun, T. Diabetes as a risk factor to cancer: Functional role of fermented papaya preparation as phytonutraceutical adjunct in the treatment of diabetes and cancer. Mutat. Res. Fundam. Mol. Mech. Mutagenes. 2014, 768, 60–68.

- Basu, A.; Rhone, M.; Lyons, T.J. Berries: Emerging impact on cardiovascular health. Nutr. Rev. 2010, 68, 168–177.

- Seeram, N.P. Emerging Research Supporting the Positive Effects of Berries on Human Health and Disease Prevention. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5685–5686.

- Gopalan, A.; Reuben, S.C.; Ahmed, S.; Darvesh, A.S.; Hohmann, J.; Bishayee, A. The health benefits of blackcurrants. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 795–809.

- Lavefve, L.; Howard, L.R.; Carbonero, F. Berry polyphenols metabolism and impact on human gut microbiota and health. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 45–65.

- Vuong, T.; Martin, L.; Matar, C. Antioxidant activity of fermented berry juices and their effects on nitric oxide and tumor necrosis factor-alpha production in macrophages 264.7 gamma no(–) cell line. J. Food Biochem. 2006, 30, 249–268.

- Vuong, T.; Martineau, L.C.; Ramassamy, C.; Matar, C.; Haddad, P.S. Fermented Canadian lowbush blueberry juice stimulates glucose uptake and AMP-activated protein kinase in insulin-sensitive cultured muscle cells and adipocytes. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2007, 85, 956–965.

- Kristo, A.S.; Klimis-Zacas, D.; Sikalidis, A.K. Protective role of dietary berries in cancer. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 37.

- Boath, A.S.; Grussu, D.; Stewart, D.; McDougall, G.J. Berry Polyphenols Inhibit Digestive Enzymes: A Source of Potential Health Benefits? Food Dig. 2012, 3, 1–7.

- Johnson, M.H.; de Mejia, E.G.; Fan, J.; Lila, M.A.; Yousef, G.G. Anthocyanins and proanthocyanidins from blueberry–blackberry fermented beverages inhibit markers of inflammation in macrophages and carbohydrate-utilizing enzymes in vitro. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2013, 57, 1182–1197.

- Martin, L.J.; Matar, C. Increase of antioxidant capacity of the lowbush blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) during fermentation by a novel bacterium from the fruit microflora. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 1477–1484.

- Johnson, M.H.; Lucius, A.; Meyer, T.; Gonzalez de Mejia, E. Cultivar Evaluation and Effect of Fermentation on Antioxidant Capacity and in Vitro Inhibition of α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase by Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corombosum). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 8923–8930.

- Linkner, E.; Humphreys, C. Chapter 32—Insulin Resistance and the Metabolic Syndrome. In Integrative Medicine, 4th ed.; Rakel, D., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 320–333.e325.

- Kalt, W.; Cassidy, A.; Howard, L.R.; Krikorian, R.; Stull, A.J.; Tremblay, F.; Zamora-Ros, R. Recent Research on the Health Benefits of Blueberries and Their Anthocyanins. Adv. Nutr. 2020, 11, 224–236.

- Zorzi, M.; Gai, F.; Medana, C.; Aigotti, R.; Morello, S.; Peiretti, P.G. Bioactive Compounds and Antioxidant Capacity of Small Berries. Foods 2020, 9, 623.

- Vuong, T.; Mallet, J.-F.; Ouzounova, M.; Rahbar, S.; Hernandez-Vargas, H.; Herceg, Z.; Matar, C. Role of a polyphenol-enriched preparation on chemoprevention of mammary carcinoma through cancer stem cells and inflammatory pathways modulation. J. Transl. Med. 2016, 14, 13.

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, Z.; Yin, B.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Enhancement of functional characteristics of blueberry juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT 2020, 110590.

- Vuong, T.; Benhaddou-Andaloussi, A.; Brault, A.; Harbilas, D.; Martineau, L.C.; Vallerand, D.; Ramassamy, C.; Matar, C.; Haddad, P.S. Antiobesity and antidiabetic effects of biotransformed blueberry juice in KKAy mice. Int. J. Obes. 2009, 33, 1166–1173.

- Vuong, T.; Matar, C.; Ramassamy, C.; Haddad, P.S. Biotransformed blueberry juice protects neurons from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway alterations. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 104, 656–663.

- Yücel, G.; Zhao, Z.; El-Battrawy, I.; Lan, H.; Lang, S.; Li, X.; Buljubasic, F.; Zimmermann, W.-H.; Cyganek, L.; Utikal, J.; et al. Lipopolysaccharides induced inflammatory responses and electrophysiological dysfunctions in human-induced pluripotent stem cell derived cardiomyocytes. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2935.

- Peñas, E.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J. Chapter 24—Sauerkraut: Production, Composition, and Health Benefits. In Fermented Foods in Health and Disease Prevention; Frias, J., Martinez-Villaluenga, C., Peñas, E., Eds.; Academic Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 557–576.

- Cordeiro Caillot, A.R.; de Lacerda Bezerra, I.; Palhares, L.C.G.F.; Santana-Filho, A.P.; Chavante, S.F.; Sassaki, G.L. Structural characterization of blackberry wine polysaccharides and immunomodulatory effects on LPS-activated RAW 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. 2018, 257, 143–149.

- Moilanen, E.; Vapaatalo, H. Nitric Oxide in Inflammation and Immune Response. Ann. Med. 1995, 27, 359–367.

- Liu, B.; Gao, H.M.; Wang, J.Y.; Jeohn, G.H.; Cooper, C.L.; Hong, J.S. Role of nitric oxide in inflammation-mediated neurodegeneration. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2002, 962, 318–331.

- Achari, A.E.; Jain, S.K. Adiponectin, a Therapeutic Target for Obesity, Diabetes, and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 1321.

- Bruun, J.M.; Lihn, A.S.; Verdich, C.; Pedersen, S.B.; Toubro, S.; Astrup, A.; Richelsen, B. Regulation of adiponectin by adipose tissue-derived cytokines: In vivo and in vitro investigations in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 285, E527–E533.

- Ryu, J.-Y.; Kang, H.R.; Cho, S.K. Changes Over the Fermentation Period in Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant and Anticancer Activities of Blueberries Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. J. Food Sci. 2019, 84, 2347–2356.

- Cheng, Y.; Wu, T.; Chu, X.; Tang, S.; Cao, W.; Liang, F.; Fang, Y.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Fermented blueberry pomace with antioxidant properties improves fecal microbiota community structure and short chain fatty acids production in an in vitro mode. LWT 2020, 125, 109260.

- Cheng, Y.; Tang, S.; Huang, Y.; Liang, F.; Fang, Y.; Pan, S.; Wu, T.; Xu, X. Lactobacillus casei-fermented blueberry pomace augments sIgA production in high-fat diet mice by improving intestinal microbiota. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 6552–6564.

- Song, B.; Zheng, C.; Zha, C.; Hu, S.; Yang, X.; Wang, L.; Xiao, H. Dietary leucine supplementation improves intestinal health of mice through intestinal SIgA secretion. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 128, 574–583.

- Cheng, Y.; Wu, T.; Tang, S.; Liang, F.; Fang, Y.; Cao, W.; Pan, S.; Xu, X. Fermented blueberry pomace ameliorates intestinal barrier function through the NF-κB-MLCK signaling pathway in high-fat diet mice. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 3167–3179.

- Ma, T.Y.; Boivin, M.A.; Ye, D.; Pedram, A.; Said, H.M. Mechanism of TNF-α modulation of Caco-2 intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier: Role of myosin light-chain kinase protein expression. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2005, 288, G422–G430.

- Ahrén, I.L.; Xu, J.; Önning, G.; Olsson, C.; Ahrné, S.; Molin, G. Antihypertensive activity of blueberries fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum DSM 15313 and effects on the gut microbiota in healthy rats. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 719–726.

- Xu, J.; Ahrén, I.L.; Prykhodko, O.; Olsson, C.; Ahrné, S.; Molin, G. Intake of Blueberry Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum Affects the Gut Microbiota of L-NAME Treated Rats. Evid. Based Complement Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 809128.

- Canfora, E.E.; Jocken, J.W.; Blaak, E.E. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2015, 11, 577–591.

- Overall, J.; Bonney, S.A.; Wilson, M.; Beermann, A.; Grace, M.H.; Esposito, D.; Lila, M.A.; Komarnytsky, S. Metabolic Effects of Berries with Structurally Diverse Anthocyanins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, 422.

- Kaume, L.; Howard, L.R.; Devareddy, L. The Blackberry Fruit: A Review on Its Composition and Chemistry, Metabolism and Bioavailability, and Health Benefits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 5716–5727.

- Mudnic, I.; Budimir, D.; Modun, D.; Gunjaca, G.; Generalic, I.; Skroza, D.; Katalinic, V.; Ljubenkov, I.; Boban, M. Antioxidant and vasodilatory effects of blackberry and grape wines. J. Med. Food 2012, 15, 315–321.

- Pucel, N.W. Improvement of Functional Bioactivity in Pear: Blackberry Synergies with Lactic Acid Fermentation for Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension Management. Master’s thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst, Amherst, MA, USA, 2013.

- Joh, Y.; Maness, N.; McGlynn, W. Antioxidant Properties of “Natchez” and “Triple Crown” Blackberries Using Korean Traditional Winemaking Techniques. Int. J. Food Sci. 2017, 2017, 5468149.

- Johnson, M.H.; Wallig, M.; Luna Vital, D.A.; de Mejia, E.G. Alcohol-free fermented blueberry–blackberry beverage phenolic extract attenuates diet-induced obesity and blood glucose in C57BL/6J mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2016, 31, 45–59.

- Sarvottam, K.; Yadav, R.K. Obesity-related inflammation & cardiovascular disease: Efficacy of a yoga-based lifestyle intervention. Indian J. Med. Res. 2014, 139, 822–834.

- Bai, Y.; Sun, Q. Macrophage recruitment in obese adipose tissue. Obes. Rev. 2015, 16, 127–136.

- Garcia-Diaz, D.F.; Johnson, M.H.; de Mejia, E.G. Anthocyanins from fermented berry beverages inhibit inflammation-related adiposity response in vitro. J. Med. Food 2014, 18, 489–496.

- Chen, M.; Zhang, G.; Yi, M.; Chen, X.; Li, J.; Xie, H.; Chen, X. Effect of UVA irradiation on proliferation and NO/iNOS system of human skin fibroblast. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban J. Cent. South Univ. Med Sci. 2009, 34, 705–711.

- Surowiak, P.; Gansukh, T.; Donizy, P.; Halon, A.; Rybak, Z. Increase in cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) expression in keratinocytes and dermal fibroblasts in photoaged skin. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2014, 13, 195–201.

- Kim, H.-R.; Jeong, D.-H.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.-W.; Sin, H.-S.; Yu, K.-Y.; Jeong, S.-I.; Kim, S.-Y. Fermentation of Blackberry with L. plantarum JBMI F5 Enhance the Protection Effect on UVB-Mediated Photoaging in Human Foreskin Fibroblast and Hairless Mice through Regulation of MAPK/NF-κB Signaling. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2429.

- Bigot, N.; Beauchef, G.; Hervieu, M.; Oddos, T.; Demoor, M.; Boumediene, K.; Galéra, P. NF-κB accumulation associated with COL1A1 transactivators defects during chronological aging represses type I collagen expression through a–112/–61-bp region of the COL1A1 promoter in human skin fibroblasts. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 2360–2367.

- Tanaka, K.; Asamitsu, K.; Uranishi, H.; Iddamalgoda, A.; Ito, K.; Kojima, H.; Okamoto, T. Protecting skin photoaging by NF-κB inhibitor. Curr. Drug Metab. 2010, 11, 431–435.

- Marques, C.; Fernandes, I.; Meireles, M.; Faria, A.; Spencer, J.P.E.; Mateus, N.; Calhau, C. Gut microbiota modulation accounts for the neuroprotective properties of anthocyanins. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11341.

- Park, S.; Cho, S.M.; Jin, B.R.; Yang, H.J.; Yi, Q.J. Mixture of blackberry leaf and fruit extracts alleviates non-alcoholic steatosis, enhances intestinal integrity, and increases Lactobacillus and Akkermansia in rats. Exp. Biol. Med. 2019, 244, 1629–1641.

More