Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a degenerative brain disorder characterized by a progressive decline in memory and cognition, mostly affecting the elderly. Numerous functional bioactives have been reported in marine organisms, and anti-Alzheimer’s agents derived from marine resources have gained attention as a promising approach to treat AD pathogenesis. Marine sterols have been investigated for several health benefits, including anti-cancer, anti-obesity, anti-diabetes, anti-aging, and anti-Alzheimer’s activities, owing to their anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties. Marine sterols interact with various proteins and enzymes participating via diverse cellular systems such as apoptosis, the antioxidant defense system, immune response, and cholesterol homeostasis.

- cholesterol homeostasis

- marine steroids

- fucosterol

- neurodegeneration

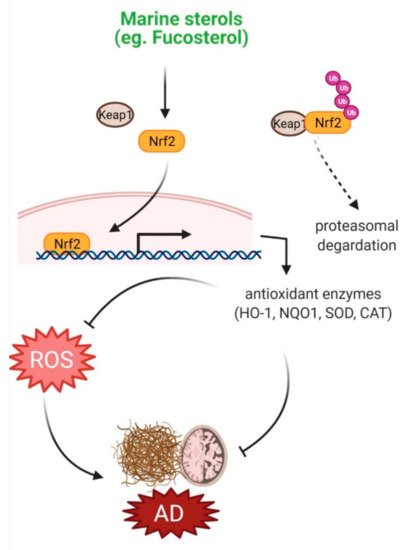

1. Protection against Oxidative Stress

Fighting off oxidative stress, cells are equipped with antioxidant defense systems, comprising antioxidant enzymes such as catalase (CAT), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), and superoxide dismutase (SOD), and non-enzymatic antioxidants, such as glutathione and ascorbate. Dietary consumption of natural compounds can also strengthen the cellular antioxidant defense system through their adaptogenic potential [1]. Natural compounds can also target signaling pathways, including Nrf2/heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), and thereby, potentiate intrinsic defense system [2]. Marine sterols were shown to protect against oxidative injury in various experimental models through their antioxidant property. Fucosterol and two other sterols, 3,6,17-trihydroxy-stigmasta-4,7,24(28)-triene and 14,15,18,20-diepoxyturbinarin, isolated from

protected against carbon tetrachloride (CCl

)-induced oxidative stress by enhancing SOD, CAT, and GPx1 levels in CCl

-challenged rats [3]. Fucosterol isolated from

inhibited ROS production in tert-butyl hydroperoxide (t-BHP)-induced RAW264.7 macrophages [4]. In tert-BHP- and tacrine-challenged HepG2cell, fucosterol treatment caused a reduction in ROS and thereby attenuated oxidative stress by increasing glutathione level [5]. Fucosterol from

protected against oxidative stress in particulate matter-induced injury and inflammation model of A549 human lung epithelial cells by accumulating SOD, CAT, and HO-1 in the cytosol, and Nrf2 levels in the nucleus [6]. A steroidal antioxidant, 7-dehydroerectasteroid F, isolated from the soft coral

was shown to protect against H

O

-induced oxidative damage in PC12 cells by enhancing nuclear translocation of Nrf2 and subsequent activation of HO-1 expression [7]. These protective effects of marine sterols against oxidative injury suggest their potential efficacy against oxidative stress-associated neurological disorders, including AD (

).

Effects of marine sterols on oxidative stress. Various sterols including fucosterol have been reported to activate Nrf2 signaling, which upregulates expression of various antioxidant enzymes, such as HO-1, NQO1, SOD and CAT. These enzymes inhibit ROS production and thereby may attenuate oxidative stress in AD pathology.

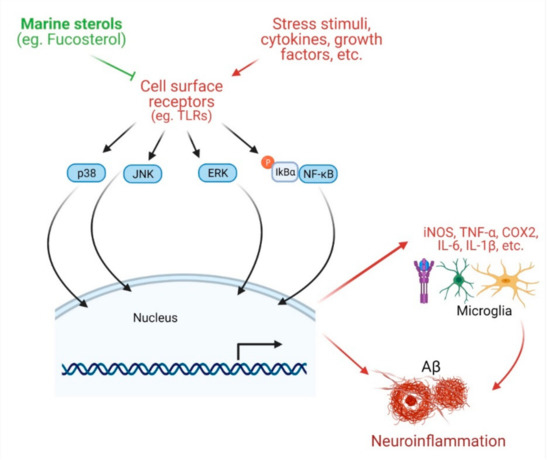

2. Protection against Neuroinflammation

In microglia challenged with extrinsic and intrinsic toxic stimuli, there is an elevated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase (COX-2), and secretion of inflammatory mediators such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and interleukin-1β (IL-1β), which can stimulate neurons to cause degeneration, ultimately leading to AD. Natural products, including phytosterols that attenuate inflammatory signals can be beneficial in the management of AD [8][9][10]. Mounting evidence suggests anti-inflammatory potentials of marine sterols. Fucosterol treatment of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- or Aβ-stimulated microglial cells ameliorated inflammation by lowering the secretion of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, nitric oxide (NO), and PGE2 [11]. Fucosterol attenuated the inflammatory response in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 macrophages by downregulating COX-2 and iNOS expression and suppressing NF-κB signaling [4]. Fucosterol can also attenuate LPS-mediated inflammation by suppressing NF-κB activation and stimulating alveolar macrophages [12]. In CoCl

-challenged cells, fucosterol inhibited inflammatory response by lowering the production of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β [13]. Fucosterol attenuated particulate matter-induced inflammation by inhibiting activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB and phosphorylation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1/2 (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal kinases (JNK), and COX-2 [6]. Fucosterol of

downregulated the transcription of iNOS, TNF-α, and IL-6, and inhibited their production. Moreover, fucosterol inhibited LPS-mediated activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB. In addition, fucosterol attenuated activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases 3/6 (MKK3/6) and MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) of the MAPK pathway, suggesting that the anti-inflammatory effects of fucosterol may be, at least in part, associated with the inactivation of NF-κB and p38 MAPK pathways [14].

Apart from algal sterols, there are some other marine sterols that are also important as anti-inflammatory agents. Two steroids, 5α-pregn-20-en-3β-ol and 5α-cholestan-3,6-dione, isolated from an octocoral

, were shown to inhibit LPS-induced NO production in activated RAW264.7 murine macrophage cells [15]. Another octocoral sterol, dendronesterones D, isolated from

sp., inhibited the expression of iNOS and COX-2, and thereby protected against inflammation [16]. Anti-inflammatory effects of marine sterols suggest their potential in protecting against neuroinflammation in AD pathology (

).

Effects of marine sterols on inflammation. Various stress stimuli, growth factors, and cytokines bind with diversified cell surface receptors (such as TLRs) and mediate different downstream signaling pathways, such as p38 MAPK, JNK, ERK, and NF-κB. These enter into the nucleus for transcription of various pro-inflammatory cytokines, including iNOS, TNFα, COX2, IL-6, and IL1β. All of these ultimately help in the formation of Aβ plaque in brain. Various sterols including fucosterol have been reported to disturb the cell surface receptors as well as major signaling systems leading to inhibition of inflammatory response.

3. Marine Sterols as Cholinesterase Inhibitors

The cholinergic deficit has been established as a clinical consequence of AD pathology. Cholinesterase inhibitors that can temporarily slow down cholinergic neurotransmission can improve AD outcomes. Marine sterols have also been shown to inhibit the activity of cholinesterase. Fucosterol and 24-hydroperoxy 24-vinylcholesterol showed inhibition against butyrylcholinesterase (BChE) with IC

values of 421.72 ± 1.43 and 176.46 ± 2.51 μM, respectively [17]. In another study, fucosterol exhibited dose-dependent inhibition against acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and BChE activities [11]. Enzyme kinetics and structural analysis demonstrated that fucosterol acts as a non-competitive inhibitor to AChE [18].

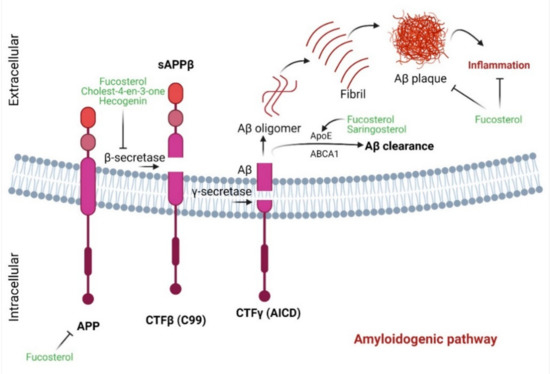

4. Marine Sterols as β-Secretase Inhibitors

The aggregation of Aβ represents a characteristic hallmark of AD. β-secretase, which catalyzes the initial breakdown of amyloid precursor protein (APP) to generate Aβ, may represent a promising target for the development of an anti-AD agent [19]. However, evidence suggests that complete inhibition of β-secretase activity might have unintended sequelae with behavioral deficits [20]. Natural products that bear reversible and non-competitive binding patterns with β-secretase may therefore bear therapeutic promise against AD. Natural products, including marine sterols, possess anti-amyloidogenic potential. Fucosterol can be such a potential candidate due to its anti-β-secretase activity [21]. The mode of inhibition is of noncompetitive type, indicating that fucosterol could be an effective and safer inhibitor. Additionally, as shown in computational analysis, fucosterol can be docked on the active site of β-secretase via hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions [22]. Moreover, fucosterol shows competitive binding energies of −10.1 [21] and −19.88 kcal/mol [22], respectively, indicating that hydrogen bonding may ensure close association with enzyme active site, leading to a more effective β-secretase inhibition. Moreover, hecogenin and cholest-4-

-3-one isolated from fat innkeeper worm

exhibited anti-β-secretase activity with EC50 of 390.6 µM and 116.3 µM, respectively [23]. With this evidence, these marine sterols can be a potent anti-amyloidogenic agent for use against AD (

).

Effects of marine sterols on APP processing pathways in AD. In the amyloidogenic pathway, APP is cleaved by β-secretase, which produces a soluble amyloid precursor protein β (sAPP β) and a C-terminal fragment β (CTFβ) or C99 fragment. The C99 fragment is cleaved by γ-secretase to generate Aβ and C-terminal fragment γ (CTFγ) or AICD. Further, Aβ constructs Aβ oligomers which ultimately form fibrils and Aβ plaques. Interestingly, fucosterol and other marine sterols inhibit β-secretase, protect against Aβ-mediated inflammation and promote Aβ-clearance.

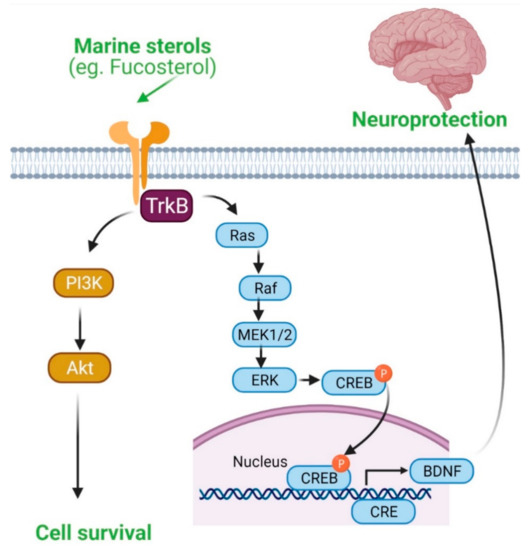

5. Marine Sterols as Neuroprotective Agent

Aβ aggregation initiates neuroinflammation and thereby can contribute to the pathobiology of AD. Marine sterols have been shown to protect against Aβ-induced cytotoxicity and clear Aβ in several studies. Fucosterol protected against Aβ

(sAβ

)-mediated cytotoxicity and suppressed glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78) expression in cultured hippocampal neurons by upregulating tropomyosin receptor kinase B (TrkB)-mediated ERK1/2 signaling [24] (

). These in vitro effects of fucosterol were further translated into an in vivo model, in which fucosterol co-treatment ameliorated sAβ

-induced cognitive impairment in aging rats through suppression of GRP78 expression and upregulation of BDNF expression in the dentate gyrus [24]. In Aβ-induced SH-SY5Y cells, fucosterol pretreatment attenuated neurotoxicity by upregulating neuroglobin (Ngb) mRNA expression [25]. Fucosterol preconditioning also decreased APP mRNA and lowered Aβ levels in activated SH-SY5Y cells [25]. Supplementation of astrocytes with 24(S)-saringosterol caused an increase in ApoE secretion. Furthermore, supplementation of microglia with conditioned medium of 24(S)-saringosterol-treated astrocytes augmented microglial clearance of Aβ

. 24(S)-saringosterol reduces Aβ

release in APP overexpressing neuronal N2a cells [26]. 16-

-desmethylasporyergosterol-β-

-mannoside isolated from marine-derived fungus

exhibited a moderate Aβ-42 lowering activity in APP-overexpressing aftin-5-treated N2a cells [27]. 4-methylenecholestane-3β,5α,6β,19-tetraol attenuated glutamate-induced neuronal injury, prevented N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-induced intracellular calcium increase, and inhibited NMDA currents, suggesting that this marine-derived sterol could also have therapeutic potential against glutamate excitotoxicity [28].

Activation of BDNF-dependent pro-survival pathway by fucosterol. TrkB/PI3K/Akt and TrkB/ERK signaling pathways are involved in neuroprotection.

6. Marine Sterols as Regulators of Cholesterol Homeostasis

Cholesterol is known to regulate cell-to-cell communication and transmembrane signaling [29], and is critical in the development and maintenance of central nervous system (CNS) neurons. A defect in cholesterol metabolism results in synaptic dysfunction, oxidative stress and inflammation, triggering the onset of AD pathology [30]. Activation of LXR-β upregulates several genes of reverse cholesterol transport, including apolipoprotein E (ApoE), ATP-binding cassette transporter (ABCA1), ATP binding cassette subfamily G member 1 (ABCG1), and sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 (SREBP1), and thereby this nuclear receptor plays a significant role in the protection against neurodegeneration [31][32]. Upon ligand activation, LXR-β attenuated dopaminergic loss [33] and reduced the toxic burden of mutant huntingtin [34], and also accelerated Aβ clearance [35]. Experimentally, acting as a selective LXR-β agonist, fucosterol augmented the expression of LXR target genes encoding ABCA1, ABCG1, and ApoE [36][37]. This evidence demonstrates that fucosterol may produce similar LXR-β-mediated effects to aid in brain cholesterol homeostasis and play a pivotal role against AD pathology involving Aβ clearance via ABC/SHREBP1/ApoE-dependent pathways (

). Saringasterol is also a selective LXRβ agonist and promoted the transcriptional activation of ABCA1, ABCG1, and SREBP-1c in multiple cell lines and thus is suggested to be a potent natural cholesterol-lowering agent [36].

References

- Lee, J.; Jo, D.G.; Park, D.; Chung, H.Y.; Mattson, M.P. Adaptive cellular stress pathways as therapeutic targets of dietary phytochemicals: Focus on the nervous system. Pharmacol. Rev. 2014, 66, 815–868.

- Tavakkoli, A.; Iranshahi, M.; Hasheminezhad, S.H.; Hayes, A.W.; Karimi, G. The neuroprotective activities of natural products through the Nrf2 upregulation. Phytother. Res. 2019, 33, 2256–2273.

- Lee, S.; Lee, Y.S.; Jung, S.H.; Kang, S.S.; Shin, K.H. Anti-oxidant activities of fucosterol from the marine algae Pelvetia siliquosa. Arch. Pharmacal Res. 2003, 26, 719–722.

- Jung, H.A.; Jin, S.E.; Ahn, B.R.; Lee, C.M.; Choi, J.S. Anti-inflammatory activity of edible brown alga Eisenia bicyclis and its constituents fucosterol and phlorotannins in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. Int. J. Publ. Br. Ind. Biol. Res. Assoc. 2013, 59, 199–206.

- Choi, J.S.; Han, Y.R.; Byeon, J.S.; Choung, S.Y.; Sohn, H.S.; Jung, H.A. Protective effect of fucosterol isolated from the edible brown algae, Ecklonia stolonifera and Eisenia bicyclis, on tert-butyl hydroperoxide- and tacrine-induced HepG2 cell injury. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2015, 67, 1170–1178.

- Fernando, I.P.S.; Jayawardena, T.U.; Kim, H.-S.; Lee, W.W.; Vaas, A.P.J.P.; De Silva, H.I.C.; Abayaweera, G.S.; Nanayakkara, C.M.; Abeytunga, D.T.U.; Lee, D.-S.; et al. Beijing urban particulate matter-induced injury and inflammation in human lung epithelial cells and the protective effects of fucosterol from Sargassum binderi (Sonder ex J. Agardh). Environ. Res. 2019, 172, 150–158.

- Wu, J.; Xi, Y.; Huang, L.; Li, G.; Mao, Q.; Fang, C.; Shan, T.; Jiang, W.; Zhao, M.; He, W.; et al. A Steroid-Type Antioxidant Targeting the Keap1/Nrf2/ARE Signaling Pathway from the Soft Coral Dendronephthya gigantea. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 2567–2575.

- Lv, H.; Qi, Z.; Wang, S.; Feng, H.; Deng, X.; Ci, X. Asiatic Acid Exhibits Anti-inflammatory and Antioxidant Activities against Lipopolysaccharide and d-Galactosamine-Induced Fulminant Hepatic Failure. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 785.

- Wang, T.; Xiang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X.; Fang, C.; Song, S.; Li, C.; Yu, H.; Wang, H.; Yan, L.; et al. (−)-Epigallocatechin Gallate Targets Notch to Attenuate the Inflammatory Response in the Immediate Early Stage in Human Macrophages. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 433.

- Dash, R.; Mitra, S.; Ali, M.C.; Oktaviani, D.F.; Hannan, M.A.; Choi, S.M.; Moon, I.S. Phytosterols: Targeting Neuroinflammation in Neurodegeneration. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2021, 27, 383–401.

- Wong, C.H.; Gan, S.Y.; Tan, S.C.; Gany, S.A.; Ying, T.; Gray, A.I.; Igoli, J.; Chan, E.W.L.; Phang, S.M. Fucosterol inhibits the cholinesterase activities and reduces the release of pro-inflammatory mediators in lipopolysaccharide and amyloid-induced microglial cells. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 3261–3270.

- Li, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, G.; Sun, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. Fucosterol attenuates lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury in mice. J. Surg. Res. 2015, 195, 515–521.

- Sun, Z.; Mohamed, M.A.A.; Park, S.Y.; Yi, T.H. Fucosterol protects cobalt chloride induced inflammation by the inhibition of hypoxia-inducible factor through PI3K/Akt pathway. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 29, 642–647.

- Yoo, M.S.; Shin, J.S.; Choi, H.E.; Cho, Y.W.; Bang, M.H.; Baek, N.I.; Lee, K.T. Fucosterol isolated from Undaria pinnatifida inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced production of nitric oxide and pro-inflammatory cytokines via the inactivation of nuclear factor-kappaB and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase in RAW264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. 2012, 135, 967–975.

- Ngoc, N.T.; Hanh, T.T.H.; Cuong, N.X.; Nam, N.H.; Thung, D.C.; Ivanchina, N.V.; Dang, N.H.; Kicha, A.A.; Kiem, P.V.; Minh, C.V. Steroids from Dendronephthya mucronata and Their Inhibitory Effects on Lipopolysaccharide-Induced No Formation in RAW264.7 Cells. Chem. Nat. Compd. 2019, 55, 1090–1093.

- Huynh, T.H.; Chen, P.C.; Yang, S.N.; Lin, F.Y.; Su, T.P.; Chen, L.Y.; Peng, B.R.; Hu, C.C.; Chen, Y.Y.; Wen, Z.H.; et al. New 1,4-Dienonesteroids from the Octocoral Dendronephthya sp. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 530.

- Yoon, N.Y.; Chung, H.Y.; Kim, H.R.; Choi, J.S. Acetyl- and butyrylcholinesterase inhibitory activities of sterols and phlorotannins from Ecklonia stolonifera. Fish. Sci. 2008, 74, 200–207.

- Castro-Silva, E.S.; Bello, M.; Hernandez-Rodriguez, M.; Correa-Basurto, J.; Murillo-Alvarez, J.I.; Rosales-Hernandez, M.C.; Munoz-Ochoa, M. In vitro and in silico evaluation of fucosterol from Sargassum horridum as potential human acetylcholinesterase inhibitor. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2019, 37, 3259–3268.

- Ghosh, A.K.; Brindisi, M.; Tang, J. Developing beta-secretase inhibitors for treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2012, 120 (Suppl. 1), 71–83.

- Koelsch, G. BACE1 Function and Inhibition: Implications of Intervention in the Amyloid Pathway of Alzheimer’s Disease Pathology. Molecules 2017, 22, 1723.

- Jung, H.A.; Ali, M.Y.; Choi, R.J.; Jeong, H.O.; Chung, H.Y.; Choi, J.S. Kinetics and molecular docking studies of fucosterol and fucoxanthin, BACE1 inhibitors from brown algae Undaria pinnatifida and Ecklonia stolonifera. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 89, 104–111.

- Hannan, M.A.; Dash, R.; Sohag, A.A.M.; Moon, I.S. Deciphering Molecular Mechanism of the Neuropharmacological Action of Fucosterol through Integrated System Pharmacology and In Silico Analysis. Mar. Drugs 2019, 17, 639.

- Zhu, Y.-Z.; Liu, J.-W.; Wang, X.; Jeong, I.-H.; Ahn, Y.-J.; Zhang, C.-J. Anti-BACE1 and Antimicrobial Activities of Steroidal Compounds Isolated from Marine Urechis unicinctus. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 94.

- Oh, J.H.; Choi, J.S.; Nam, T.J. Fucosterol from an Edible Brown Alga Ecklonia stolonifera Prevents Soluble Amyloid Beta-Induced Cognitive Dysfunction in Aging Rats. Mar. Drugs 2018, 16, 368.

- Gan, S.Y.; Wong, L.Z.; Wong, J.W.; Tan, E.L. Fucosterol exerts protection against amyloid β-induced neurotoxicity, reduces intracellular levels of amyloid β and enhances the mRNA expression of neuroglobin in amyloid β-induced SH-SY5Y cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 121, 207–213.

- Bogie, J.; Hoeks, C.; Schepers, M.; Tiane, A.; Cuypers, A.; Leijten, F.; Chintapakorn, Y.; Suttiyut, T.; Pornpakakul, S.; Struik, D.; et al. Dietary Sargassum fusiforme improves memory and reduces amyloid plaque load in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 4908.

- Harms, H.; Kehraus, S.; Nesaei-Mosaferan, D.; Hufendieck, P.; Meijer, L.; König, G.M. Aβ-42 lowering agents from the marine-derived fungus Dichotomomyces cejpii. Steroids 2015, 104, 182–188.

- Leng, T.; Liu, A.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhou, S.; Li, Q.; Zhu, W.; Zhou, Y.; Su, X.; Huang, Y.; et al. Naturally occurring marine steroid 24-methylenecholestane-3β,5α,6β,19-tetraol functions as a novel neuroprotectant. Steroids 2016, 105, 96–105.

- Morinaga, T.; Yamaguchi, N.; Nakayama, Y.; Tagawa, M.; Yamaguchi, N. Role of Membrane Cholesterol Levels in Activation of Lyn upon Cell Detachment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1811.

- Martin, M.G.; Pfrieger, F.; Dotti, C.G. Cholesterol in brain disease: Sometimes determinant and frequently implicated. EMBO Rep. 2014, 15, 1036–1052.

- Ito, A.; Hong, C.; Rong, X.; Zhu, X.; Tarling, E.J.; Hedde, P.N.; Gratton, E.; Parks, J.; Tontonoz, P. LXRs link metabolism to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane composition and TLR signaling. eLife 2015, 4, e08009.

- Xu, P.; Li, D.; Tang, X.; Bao, X.; Huang, J.; Tang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, H.; Fan, X. LXR agonists: New potential therapeutic drug for neurodegenerative diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2013, 48, 715–728.

- Dai, Y.B.; Tan, X.J.; Wu, W.F.; Warner, M.; Gustafsson, J.A. Liver X receptor beta protects dopaminergic neurons in a mouse model of Parkinson disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 13112–13117.

- Futter, M.; Diekmann, H.; Schoenmakers, E.; Sadiq, O.; Chatterjee, K.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Wild-type but not mutant huntingtin modulates the transcriptional activity of liver X receptors. J. Med. Genet. 2009, 46, 438–446.

- Wolf, A.; Bauer, B.; Hartz, A.M. ABC Transporters and the Alzheimer’s Disease Enigma. Front. Psychiatry 2012, 3, 54.

- Chen, Z.; Liu, J.; Fu, Z.; Ye, C.; Zhang, R.; Song, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H.; Ying, H.; Liu, H. 24(S)-Saringosterol from edible marine seaweed Sargassum fusiforme is a novel selective LXRbeta agonist. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6130–6137.

- Hoang, M.-H.; Jia, Y.; Jun, H.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Lee, B.Y.; Lee, S.-J. Fucosterol Is a Selective Liver X Receptor Modulator That Regulates the Expression of Key Genes in Cholesterol Homeostasis in Macrophages, Hepatocytes, and Intestinal Cells. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 11567–11575.