Urothelial carcinoma (UC) is the most frequent malignancy of the urinary system and is ranked the sixth most diagnosed cancer in men worldwide. Around 70–75% of newly diagnosed UC manifests as the non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) subtype, which can be treated by a transurethral resection of the tumor. However, patients require life-long monitoring due to its high rate of recurrence. The current gold standard for UC diagnosis, prognosis, and disease surveillance relies on a combination of cytology and cystoscopy, which is invasive, costly, and associated with comorbidities. Hence, there is considerable interest in the development of highly specific and sensitive urinary biomarkers for the non-invasive early detection of UC. In this review, we assess the performance of current diagnostic assays for UC and highlight some of the most promising biomarkers investigated to date. We also highlight some of the recent advances in single-cell technologies that may offer a paradigm shift in the field of UC biomarker discovery and precision diagnostics.

- single cell

- diagnostics

- urothelial carcinoma

- biomarker

- non-invasive

- cytology

- cystoscopy

- circulating tumor cells

1. Introduction

Bladder cancer (BC) is among the top 10 most common types of cancer worldwide, with around 550,000 new cases annually [1], and confers the highest financial burden to developed countries. BC accounts for around 3% of all new cancer diagnoses and 2.1% of all cancer-associated deaths [2], ranking it 6th highest in men and 17th in women worldwide in terms of absolute incidence. Among the 550,000 new BCs diagnosed globally in 2018, around 425,000 (77%) occurred in men and over 125,000 cases (23%) occurred in women [3].

The World Health Organization’s 2016 classification states that the three most common BCs are urothelial carcinoma (UC), squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma. Among these, UC is the most common form, accounting for 90–95% of BC cases. BC is pathologically staged as non-invasive, stromal invasive, and muscle invasive.

Different tests and procedures are used to diagnose UC. The current diagnostic technologies include urinalysis, cystoscopy, urine cytology, biopsy, urine-based biomarkers, and clinical imaging such as computerized tomography (CT) urogram or retrograde pyelogram. Urine cytology is inexpensive and commonly used for initial detection of malignant cells, whereas cystoscopy with biopsy confirms the presence of the tumor [4] and allows for pathologic staging. While urine cytology is a useful tool for detecting high-grade UCs (up to 85% and 88% sensitivity and specificity, respectively), the sensitivity for the detection of low-grade UCs remains very low (10–43.6%). Cystoscopy has a low diagnostic accuracy, especially with flat urothelial carcinoma in situ (CIS), which is missed in up to 20% of all cases [4]. Cystoscopy can also be unreliable for distinguishing between benign reactive lesions and malignant lesions, particularly in cases of prior transurethral resection (TUR) or intravesical therapy [5].

New endoscopic technologies, such as fluorescence cystoscopy, narrow-band imaging, confocal laser endomicroscopy (CLE), and optical coherence tomography have been developed to improve the rate and accuracy of detection, although these techniques are invasive, expensive, and time-consuming [5]. Therefore, the development of novel non-invasive urinary tests to detect UC-specific biomarkers has increased over the last few decades [6,7,8][6][7][8].

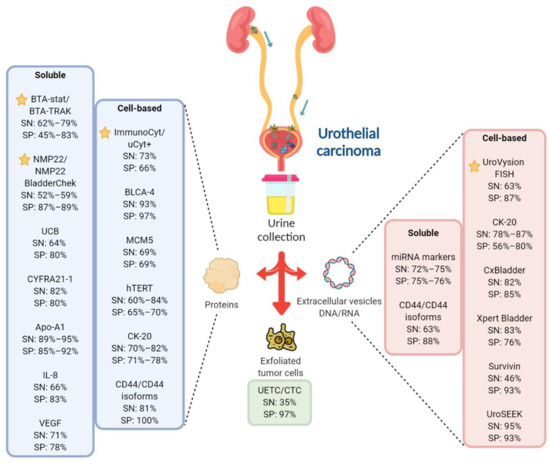

The present review provides details of the current FDA-approved diagnostic assays for UC and examines some of the emerging and novel biomarkers (Figure 1, Table 1 and Table 2).

Figure 1. Overview of the FDA-approved and investigational urinary biomarkers for UC diagnosis. Most biomarkers, both soluble and cell-based, aims to detect either exfoliated tumor cells, protein or DNA/RNA changes in urine samples. Some of the promising investigational urinary biomarkers for UC and their sensitivity/specificity are shown and compared against the FDA-approved in-vitro diagnostic (IVD) tests. indicates FDA-approved IVD tests.  Created with Biorender.com.

Created with Biorender.com.

Table 1. FDA-approved urinary biomarkers for urothelial carcinoma (UC) in-vitro diagnosis.

| Test | Biomarker | Type | Sample Material |

Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

UC, urothelial carcinoma; C, control; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; MW, molecular weight; NMP22, nuclear mitotic apparatus protein; P, patient; POC, point-of-care; SN, sensitivity; SP, specificity; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization. * weighted or pooled sensitivity/specificity.

Table 2. Novel/investigational urinary biomarkers for UC diagnosis.

| Biomarker/ Test |

Description | SN | (%) | SP | (%) |

P (n) |

Type | C | Sample Material | Method | (n) | SN (%) |

SP (%) | Remark | Reference |

|---|

| P | (n) | C | (n) | Remarks | References |

|---|

BTA-stat | Human complement factor H-related protein | Soluble |

BLCA-4 | Nuclear transcription factor | Cellular | Protein | Protein | Dipstick immunoassay or POC test | 64–69 * | 73–77 * | ELISA | 3175 | – | High false positive rates | 93 * | [9] | (meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

97 * |

BTA-Trak | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 79 | 83 | 64 | 63 |

[8] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

62–71 * | 45–81 * | 829 | – |

[10] | (meta- | analysis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

1119 (total participants) | High sensitivity and specificity for UC detection; further validation required | [ | 14] | (meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

MCM5 ^ | MCM family of proteins that assemble into hexameric complexes with DNA helicase activity; vital for DNA synthesis | Cellular | Protein | Immuno- | fluorometric assay | 69 | 69 | 210 | 1354 | Mix of low and high-grade patients; higher sensitivity but similar specificity compared with cytology |

[15] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

hTERT ^ | Catalytic subunit of telomerase, a ribonucleoprotein that synthesizes telomeres at the ends of chromosomes, thus ensuring genomic stability | Cellular | Protein | Immunocytochemistry | 84.8 | 65.2 | 101 | – | Higher sensitivity than cytology, regardless of tumor grade and stage; lower specificity than cytology; may be used as an adjunct to cytology to identify patients with increased risk of high-grade UC |

[16] |

NMP22/ | NMP22 BladderChek | NMP22 | Soluble | Protein | ELISA or | POC test | 52–59 * | 87–89 * | 5291 | – | Better at detecting high-grade UC; false positives in hematuria or inflammatory bladder conditions |

[11] | (meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

73 * | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

60.6 | 70.4 | 500 | – |

[17] |

Immuno-cyt/ | uCyt+ | High-MW form of glycosylated CEA and mucin-like antigen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CTCs ^ | Malignant epithelial cells that are shed from the primary tumor into bodily fluids | Cellular | Protein | Immunocyto chemistry | Immuno magnetic enrichment (CellSearch) | 35 * | 66 * | Cellular |

97 * | 1602 | 2161 | – | – | Unaffected by hematuria or inflammatory conditions; superior sensitivity to detect early pathological stage than cytology; test results highly dependent on specimen stability and handling | Protein | The only FDA-approved CTC test; Possibility of staining with different antibodies which allows for the identification of new CTC biomarkers | [12] |

[18](meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

(meta- | analysis) | UroVysion FISH | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CK-20 | Aneuploidy for chromosomes 3, 7, and 17, and loss of 9p21 locus | Cytokeratins are components of cytoplasmic intermediate filaments found in epithelial cells; CK-20 is expressed in urothelial carcinoma but not normal urothelial cells | Cellular | DNA | FISH | Cellular | 63 * | 87 * | 3445 | – | Complex assay that requires skilled cytopathologist; low sensitivity in the detection of low-grade UC; high rate of false positives; lack of consensus on the criteria to evaluate abnormal cells | Protein | Immuno- | staining |

[ |

70 | 71 | ] |

42 | 17 | (meta- |

Higher sensitivity than urine cytology as a UC screening test, especially for low-grade low-stage tumor |

[19] | analysis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

80 | 78 | 50 | 20 |

[20] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

82 | 77 | 174 | – |

[21] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RNA (mRNA) | RT-PCR | 78–87 | 56–80 | 3473 | – | Poor performance for low-grade tumors |

[22] | (pooled analysis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CxBladder | mRNA expression of genes (IGF, HOXA, MDK, CDC, and IL8R) | Cellular | RNA (mRNA) | RT-qPCR | 82 | 85 | 66 | 419 | Can distinguish between low-grade Ta tumors and other detected UC with high sensitivity and specificity |

[23] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Xpert | Bladder ^ | mRNA expression of genes (CRH, IGF2, UPK1B, ANXA10, and ABL1) | Cellular | RNA (mRNA) | RT-qPCR | 83 | 76 | 239 | 508 | Mainly high-grade patients |

[24] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Survivin | Inhibitor of apoptosis gene | Cellular | DNA | Bio-dot test | 64 | 93 | 117 | 92 | High sensitivity for detecting low-stage and low-grade UC; more accurate than cytology and NMP22 test; requires further validation |

[25] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UroSEEK | Mutations in FGFR3, TP53, ERBB2, CDKN2A, KRAS, HRAS, MET, PIK3CA, MLL, and VHL and TERTp alterations | Cellular | DNA | Massively parallel sequencing- | based assay (NGS/ | Sanger sequencing) | 95 | 93 | 570 | – | Higher performance than urine cytology in low-grade tumors |

[26] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AssureMDX | Mutation analysis in FGFR3, TERT, and HRAS genes and methylation analysis in OTX1, ONECUT2, and TWIST1 genes | Cellular | DNA | PCR | 93 | 86 | 97 | 103 | Mix of high and low-grade patients tested |

[27] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

57–83 | 59 | 977 | – | Patients with primary NMIBC |

[28] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UBC ^ | Soluble fragments of cytoskeletal proteins 8 and 18 | Soluble | Protein | ELISA or POC assay | 64.4 * | 80.3 * | 753 | 1072 | Increased sensitivity when used in combination with cytology; allows separation of high vs. low-grade UC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CYFRA 21-1 | Soluble fragments of cytoskeletal protein cytokeratin 19 | Soluble | Protein | Immunoradio-metric assay or ELISA | 82 * | 80 * | 1262 | 1233 | High sensitivity for detection of high-grade and CIS tumors, poor sensitivity for early detection; generates false positive in inflammatory bladder conditions |

[30] | (Meta- | analysis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Apo-A1 | Major high-density lipoprotein | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 89 | 85 | 223 | 153 | Apolipoproteins are abundant in plasma; hence, urinary concentrations are affected by hematuria |

[31] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

91.6 | 85.7 | 40 | 24 |

[32] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

95 | 92 | 86 | 62 |

[33] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

IL-8 | Leukocyte chemoattractant and angiogenic factor associated with inflammation and carcinogenesis | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 66.4 * | 83.1 * | 225 | 273 | Urinary concentrations elevated in urothelial cell carcinoma |

[34,] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

VEGF | Tumor angiogenesis factor | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 71.4 * | 78.1 * | 509 | 389 | Secreted in urine by UC cells | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CCL18 | Cytokine involved in immunoregulatory and inflammatory processes; promotes cancer cells invasiveness | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 88 | 86 | 64 | 63 | 55 high-grade, 9 low-grade |

[41] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Hyaluronidase/hyaluronic acid | Glycosidase that mainly degrades hyaluronic acid/glycosaminoglycan known to promote tumor metastasis and help avoid immune surveillance | Soluble | Protein | ELISA-like assay/zymography | 90.8 * | 82.5 * | 981 participants | May permit early detection; high sensitivity and specificity for detection of both primary and recurrent tumors; further validation in larger, multi-center trials are required |

[42] | (meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

sFAS | Anti-apoptotic protein released by UC cells | Soluble | Protein | ELISA | 88 | 89.1 | 117 | 74 | Better sensitivity in detecting low-grade UC than cytology |

[43] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

miRNA markers | Short non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression by acting at the post-transcriptional level | Soluble or | cellular | RNA (miRNA) | RT-PCR/NGS | 75 * | 75 * | 719 | 494 | Multi-miRNA assays have higher diagnostic sensitivity than single miRNA assays |

[44] | (meta- | analysis) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

72 * | 76 * | 1556 | 1347 |

[45] | (meta- | analysis) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CD44/CD44 isoforms | Ubiquitously expressed transmembrane glycoprotein involved in cell–cell interactions, cell adhesion and migration | Soluble | RNA (mRNA) | RT-PCR | 63.1 | 88.9 | 136 | 20 | 111 histological diagnosed UC, 25 benign urological disorders |

[46] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cellular | Protein | ELISA | 81 | 100 | 65 | 53 | Presence of hematuria can interfere with the assay |

[47] |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Apo-A1, apolipoprotein-A1; BLCA-4, bladder cancer 4; C: control; CTCs, circulating tumor cells; hTERT, human telomerase reverse transcriptase; MCM, minichromosome maintenance; P, patient; POC, point-of-care; NGS, next-generation sequencing; sFas, soluble Fas; SN, sensitivity; SP, specificity; UBC, urinary bladder carcinoma antigen * Weighted or pooled sensitivity/specificity. ^ In vitro diagnostic test.

2. Current Research Gaps in UC Diagnosis

Around 70–75% of newly diagnosed UC cases are non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC). The current gold standard NMIBC treatment is surgical removal via TUR. Due to the high rate (~70%) of recurrence after TUR, patients require an intensive follow-up regime that lasts many years following the initial diagnosis. This lifelong requirement for disease surveillance means UC is associated with the highest cost from diagnosis to death [48].

Urine cytology has high sensitivity in detecting high grade urothelial tumors (84%), but low sensitivity in low-grade tumors (16%) [49]; hence, urine cytology can miss low-grade NMIBC tumors. While cystoscopy remains the gold standard evaluation modality in the diagnosis of UC, it is invasive, costly, and the procedure is uncomfortable for the patient. Urine biomarkers offer a non-invasive approach to detect UC, especially for high-grade lesions and CIS, with higher sensitivity but lower specificity than urine cytology [50].

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved six urinary assays for clinical in-vitro diagnostic (IVD) use: BTA-stat, BTA-TRAK, NMP22, NMP22 BladderChek, ImmunoCyt/uCyt+, and UroVysion fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) (Table 1). While these FDA-approved IVD tests show high sensitivity in the detection of high-grade and late-stage UC, they are unable to detect low-grade malignancies and tend to give false positive results for benign inflammatory conditions. As such, they cannot be used as stand-alone diagnostic tests for UC and are used in conjunction with urine cytology or other diagnostic tests.

Novel and emerging biomarkers are continuously being developed and have shown higher sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy than urine cytology and current FDA-approved tests (Table 2). However, their use in clinical practice requires validation studies using independent cohorts and long-term follow-up. At present, there is no non-invasive biomarker that has been recommended to replace the gold standard methods currently used to detect UC.

3. FDA-Approved and Investigational UC Biomarkers

3.1. FDA-Approved IVD Tests for UC Diagnosis

Increasing research efforts have been placed in identifying a suitable urinary biomarker to reduce the necessity of invasive cystoscopy. The various FDA-approved tests are a major step towards this direction. However, the inclusion of large proportions of high-grade tumors inflates the sensitivity and specificity of many FDA-approved tests, and thus the problem of identifying low grade tumors remains.

3.2. Novel/Investigational Biomarkers for UC Detection

Some novel candidate biomarkers have been identified that require further validation and, as such, are not yet FDA-approved. The sensitivity and specificity of some of these markers are better than urine cytology or current FDA-approved tests, especially for low-grade tumors. These investigational biomarkers are grouped into two categories: cell-based and soluble. We discuss the biomarkers belonging to these two categories in the sections below, as well as CD44/CD44 isoforms and microRNA (miRNA) markers that can be classified as either cell-based or soluble.

4. Single-Cell Technologies

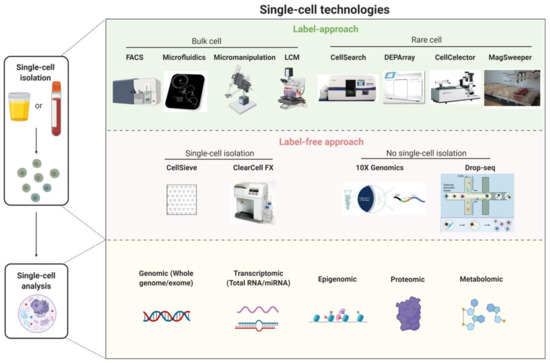

Single-cell technology has made encouraging progress in recent years such that it now provides the means to detect, isolate, and analyze rare target cells such as CTCs, cancer stem cells, or pathogenic immune cells to ultimately guide individualized treatment strategies. Most single-cell technologies involve two steps: single-cell isolation and analysis (Figure 2).

Single-cell isolation is the upstream process required prior to single-cell analysis and includes: (1) marker/phenotype-based methods for isolating single cells from bulk cell populations (e.g., fluorescence-activated cell sorting, microfluidics, micromanipulation, and laser-capture microdissection) or from rare cell populations e.g., CellSearch (Menarini Silicon Biosystems), DEPArray (Menarini Silicon Biosystems), CellCelector (Automated Lab Solutions) and MagSweeper (Illumina Inc.), and (2) label-free approaches based on the biophysical properties of cells such as size, shape, density, and stiffness [e.g., nanofabricated filters (CellSieve) and ClearCell FX (Clearbridge BioMedics)].

Some single-cell technologies (e.g., 10× Genomics, Drop-Seq) do not isolate individual target cells prior to single-cell analysis. Instead, these technologies involve encapsulating single cells with single barcoded beads in nanoliter-sized droplets and allow ultra-high-throughput phenotyping and molecular characterization of all individually encapsulated cells in the samples. Cell identity is then inferred through reverse bioinformatics analysis of the high throughput data (e.g., transcriptome analysis).

Single-cell analysis reveals the heterogeneities in morphology, function, composition, and genetic make-up of apparently identical cells. Recent advances in single-cell analysis can overcome the difficulties arising in the diagnostics for a targeted model of disease due to cell heterogeneity. Single-cell analysis techniques include genomic (whole genome/whole exome), transcriptomic, epigenomic, proteomic, and metabolomic profiles of cancer cells. Among these, single-cell genomic analysis has shown the most encouraging progress [18,95,96][18][51][52].

4.1. Applications of Single-Cell Technologies for UC Diagnosis

In UC, tumor cells that carry key genetic information of the primary tumor are shed directly by the growing tumor of the bladder into bodily fluids, such as blood or urine, making them a promising liquid biomarker for UC detection. However, in UC patients, the detection of UETCs is complicated by the presence of other urinary components such as normal urothelial cells, red blood cells, crystals, urinary cylinders, and other impurities. Furthermore, the extreme rarity and heterogeneity of CTCs/UETCs makes detecting these cells a challenging endeavor in UC diagnosis.

Advancements in single-cell technologies have increased the sensitivity and reliability of the methodologies for CTC detection, such as the CellSearch system and microfluidic-based techniques. CellSearch is an FDA-approved CTC test for the analysis of blood samples from patients with metastatic breast, prostate and colorectal cancer [97,98,99,100][53][54][55][56]. The CellSearch system has been successfully used to detect CTCs derived from patients with UC in multiple studies [68,101][57][58]. Although the number of patients enrolled and the sensitivity remains low, these early data provide a proof-of-concept for the identification of UETCs in UC patients using the CellSearch system. Microfluidic-based techniques to detect cancer cells in urine have also been recently developed and provide a novel approach to UC diagnosis. Several microfluidic devices that can detect rare UETCs have been developed [102[59][60],103], including a single-cell microscopic observation device for detecting tumor cells using droplet microfluidic technology [104][61].

Single-cell analysis can have broad applications in the UETC diagnostic workflow. Single-cell sequencing (SCS) such as whole-genome sequencing (WGS) was used by Chen et al. to analyze copy number aberrations (CNAs) in 12 UETCs captured using a novel microfluidic immunoassay approach [102][59]. The identities of the captured UETCs were successfully verified based on their genomic instability profiles, demonstrating the potential diagnostic capability of these methods for patients with UC. Single-cell miRNA profiling and single-cell epigenomic profiling also provide the exciting possibility of linking genetic and transcriptional heterogeneity in the context of cancer biology, leading to improved cancer diagnosis. The relative stability of miRNAs and DNA methylation has led to the development of diagnostic urinary biomarkers in UC [105,106,107,108,109,110,111][62][63][64][65][66][67][68]. Single-cell miRNA and epigenomic profiling have the potential to identify modifications specific to UETCs and thus guide the appropriate diagnosis. Finally, single-cell metabolomics analyses can detail the metabolic characteristics of UETCs at the single-cell level, thus identifying potential biomarkers that could be used for early UC diagnosis.

References

- Richters, A.; Aben, K.K.H.; Kiemeney, L.A. The global burden of urinary bladder cancer: An update. World J. Urol. 2020, 38, 1895–1904.

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424.

- Ferlay, J. Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Available online: (accessed on 1 August 2020).

- Lee, C.S.; Yoon, C.Y.; Witjes, J.A. The past, present and future of cystoscopy: The fusion of cystoscopy and novel imaging technology. BJU Int. 2008, 102, 1228–1233.

- Risk, M.C.; Soubra, A. Diagnostics techniques in nonmuscle invasive bladder cancer. Indian J. Urol. 2015, 31, 283–288.

- Chakraborty, A.; Dasari, S.; Long, W.; Mohan, C. Urine protein biomarkers for the detection, surveillance, and treatment response prediction of bladder cancer. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1104–1117.

- D’Costa, J.J.; Goldsmith, J.C.; Wilson, J.S.; Bryan, R.T.; Ward, D.G. A Systematic Review of the Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Urinary Protein Biomarkers in Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Bl. Cancer 2016, 2, 301–317.

- Goodison, S.; Chang, M.; Dai, Y.; Urquidi, V.; Rosser, C.J. A Multi-Analyte Assay for the Non-Invasive Detection of Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47469.

- Guo, A.; Wang, X.; Shi, J.; Sun, C.; Wan, Z. Bladder tumour antigen (BTA stat) test compared to the urine cytology in the diagnosis of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Can. Urol. Assoc. J. 2014, 8, 347–352.

- Glas, A.S.; Roos, D.; Deutekom, M.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Kurth, K.H. Tumor Markers in the Diagnosis of Primary Bladder Cancer. A Systematic Review. J. Urol. 2003, 169, 1975–1982.

- Wang, Z.; Que, H.; Suo, C.; Han, Z.; Tao, J.; Huang, Z.; Ju, X.; Tan, R.; Gu, M. Evaluation of the NMP22 BladderChek test for detecting bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 100648–100656.

- He, H.; Han, C.; Hao, L.; Zang, G. ImmunoCyt test compared to cytology in the diagnosis of bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Oncol. Lett. 2016, 12, 83–88.

- Chou, R.; Gore, J.L.; Buckley, D.; Fu, R.; Gustafson, K.; Griffin, J.C.; Grusing, S.; Selph, S. Urinary Biomarkers for Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann. Intern. Med. 2015, 163, 922–931.

- Cai, Q.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Gong, R.; Tang, Y.; Yang, K.; Li, X.; Guo, X.; Niu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Urine BLCA-4 exerts potential role in detecting patients with bladder cancers: A pooled analysis of individual studies. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 37500–37510.

- Kelly, J.D.; Dudderidge, T.J.; Wollenschlaeger, A.; Okoturo, O.; Burling, K.; Tulloch, F.; Halsall, I.; Prevost, T.; Prevost, A.T.; Vasconcelos, J.C.; et al. Bladder Cancer Diagnosis and Identification of Clinically Significant Disease by Combined Urinary Detection of Mcm5 and Nuclear Matrix Protein 22. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e40305.

- E Khalbuss, W.; Goodison, S. Immunohistochemical detection of hTERT in urothelial lesions: A potential adjunct to urine cytology. CytoJournal 2006, 3, 18.

- Allison, D.B.; Sharma, R.; Cowan, M.L.; Vandenbussche, C.J. Evaluation of Sienna Cancer Diagnostics hTERT Antibody on 500 Consecutive Urinary Tract Specimens. Acta Cytol. 2018, 62, 302–310.

- Zhang, X.; Marjani, S.L.; Hu, Z.; Weissman, S.M.; Pan, X.; Wu, S. Single-Cell Sequencing for Precise Cancer Research: Progress and Prospects. Cancer Res. 2016, 76, 1305–1312.

- Srivastava, R.; Arora, V.K.; Aggarwal, S.; Bhatia, A.; Singh, N.; Agrawal, V. Cytokeratin-20 immunocytochemistry in voided urine cytology and its comparison with nuclear matrix protein-22 and urine cytology in the detection of urothelial carcinoma. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2011, 40, 755–759.

- I Morsi, M.; I Youssef, A.; E E Hassouna, M.; El-Sedafi, A.S.; A Ghazal, A.; Zaher, E.R. Telomerase activity, cytokeratin 20 and cytokeratin 19 in urine cells of bladder cancer patients. J. Egypt. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2006, 18, 82–92.

- Golijanin, D.; Shapiro, A.; Pode, D. Immunostaining of cytokeratin 20 in cells from voided urine for detection of bladder cancer. J. Urol. 2000, 164, 1922–1925.

- Mi, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Shi, F.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Liu, X. Diagnostic accuracy of urine cytokeratin 20 for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 15, e11–e19.

- O’Sullivan, P.; Sharples, K.; Dalphin, M.; Davidson, P.; Gilling, P.; Cambridge, L.; Harvey, J.; Toro, T.; Giles, N.; Luxmanan, C.; et al. A Multigene Urine Test for the Detection and Stratification of Bladder Cancer in Patients Presenting with Hematuria. J. Urol. 2012, 188, 741–747.

- Van Valenberg, F.J.P.; Hiar, A.M.; Wallace, E.; Bridge, J.A.; Mayne, D.J.; Beqaj, S.; Sexton, W.J.; Lotan, Y.; Weizer, A.Z.; Jansz, G.K.; et al. Prospective Validation of an mRNA-based Urine Test for Surveillance of Patients with Bladder Cancer. Eur. Urol. 2019, 75, 853–860.

- Shariat, S.F.; Casella, R.; Khoddami, S.M.; Hernandez, G.; Sulser, T.; Gasser, T.C.; Lerner, S.P. Urine Detection of Survivin is a Sensitive Marker for the Noninvasive Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer. J. Urol. 2004, 171, 626–630.

- Springer, S.U.; Chen, C.-H.; Pena, M.D.C.R.; Li, L.; Douville, C.; Wang, Y.; Cohen, J.D.; Taheri, D.; Silliman, N.; Schaefer, J.; et al. Non-invasive detection of urothelial cancer through the analysis of driver gene mutations and aneuploidy. eLife 2018, 7.

- Van Kessel, K.E.; Beukers, W.; Lurkin, I.; Der Made, A.Z.-V.; Van Der Keur, K.A.; Boormans, J.L.; Dyrskjøt, L.; Márquez, M.; Ørntoft, T.F.; Real, F.X.; et al. Validation of a DNA Methylation-Mutation Urine Assay to Select Patients with Hematuria for Cystoscopy. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 590–595.

- Beukers, W.; Van Der Keur, K.A.; Kandimalla, R.; Vergouwe, Y.; Steyerberg, E.W.; Boormans, J.L.; Jensen, J.B.; Lorente, J.A.; Real, F.X.; Segersten, U.; et al. FGFR3, TERT and OTX1 as a Urinary Biomarker Combination for Surveillance of Patients with Bladder Cancer in a Large Prospective Multicenter Study. J. Urol. 2017, 197, 1410–1418.

- Ecke, T.H.; Weiß, S.; Stephan, C.; Hallmann, S.; Barski, D.; Otto, T.; Gerullis, H. UBC®Rapid Test for detection of carcinoma in situ for bladder cancer. Tumor Biol. 2017, 39, 1010428317701624.

- Huang, Y.-L.; Chen, J.; Yan, W.; Zang, D.; Qin, Q.; Deng, A. Diagnostic accuracy of cytokeratin-19 fragment (CYFRA 21-1) for bladder cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 3137–3145.

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, T.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Chang, J. Discovery of Apo-A1 as a potential bladder cancer biomarker by urine proteomics and analysis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 446, 1047–1052.

- Li, H.; Li, C.; Wu, H.; Zhang, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Chang, J. Identification of Apo-A1 as a biomarker for early diagnosis of bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Proteome Sci. 2011, 9, 21.

- Chen, Y.-T.; Chen, C.-L.; Chen, H.-W.; Chung, T.; Wu, C.-C.; Chen, C.-D.; Hsu, C.-W.; Chen, M.-C.; Tsui, K.-H.; Chang, P.-L.; et al. Discovery of Novel Bladder Cancer Biomarkers by Comparative Urine Proteomics Using iTRAQ Technology. J. Proteome Res. 2010, 9, 5803–5815.

- Abogunrin, F.; O’Kane, H.F.; Ruddock, M.W.; Stevenson, M.; Reid, C.N.; O’Sullivan, J.M.; Anderson, N.H.; O’Rourke, D.; Duggan, B.; Lamont, J.V.; et al. The impact of biomarkers in multivariate algorithms for bladder cancer diagnosis in patients with hematuria. Cancer 2011, 118, 2641–2650.

- Rosser, C.; Charles, J.; Dai, Y.; Miyake, M.; Zhang, G.; Goodison, S. Simultaneous multi-analyte urinary protein assay for bladder cancer detection. BMC Biotechnol. 2014, 14, 24.

- Sheryka, E.; Wheeler, M.A.; Hausladen, D.A.; Weiss, R.M. Urinary interleukin-8 levels are elevated in subjects with transitional cell carcinoma. Urol. 2003, 62, 162–166.

- Urquidi, V.; Chang, M.; Dai, Y.; Kim, J.; Wolfson, E.D.; Goodison, S.; Rosser, C.J. IL-8 as a urinary biomarker for the detection of bladder cancer. BMC Urol. 2012, 12, 12.

- Bian, W.; Xu, Z. Combined assay of CYFRA21-1, telomerase and vascular endothelial growth factor in the detection of bladder transitional cell carcinoma. Int. J. Urol. 2007, 14, 108–111.

- Chen, L.-M.; Chang, M.; Dai, Y.; Chai, K.; Karl, X.; Dyrskjot, L.; Sanchez-Carbayo, M.; Szarvas, T.; Zwarthoff, E.; Lokeshwar, V.; et al. External Validation of a Multiplex Urinary Protein Panel for the Detection of Bladder Cancer in a Multicenter Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 1804–1812.

- Sun, Y.; He, D.-L.; Ma, Q.; Wan, X.-Y.; Zhu, G.-D.; Li, L.; Luo, Y.; He, H.; Yang, L. Comparison of seven screening methods in the diagnosis of bladder cancer. Chin. Med. J. 2006, 119, 1763–1771.

- Urquidi, V.; Kim, J.; Chang, M.; Dai, Y.; Rosser, C.J.; Goodison, S. CCL18 in a Multiplex Urine-Based Assay for the Detection of Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e37797.

- Liang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, C.; Shi, F.; Cao, H.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, M.; Liu, X. Hyaluronic acid/Hyaluronidase as biomarkers for bladder cancer: A diagnostic meta-analysis. Neoplasma 2017, 64, 901–908.

- Srivastava, A.K.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, D.; Dalela, D.; Rath, S.K.; Bhatt, M. Clinical utility of urinary soluble Fas in screening for bladder cancer. Asia-Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 12, e215–e221.

- Lu, Q.; Cheng, Y.; Deng, X.; Yang, X.; Li, P.; Wang, Z.; Li, P.; Tao, J.; Zhang, X. Urine microRNAs as biomarkers for bladder cancer: A diagnostic meta-analysis. OncoTargets Ther. 2015, 8, 2089–2096.

- Shi, H.-B.; Yu, J.-X.; Yu, J.-X.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, C.; Li, G.-Y.; Zhao, R.-N.; Yang, X.-B. Diagnostic significance of microRNAs as novel biomarkers for bladder cancer: A meta-analysis of ten articles. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2017, 15, 1–10.

- Eissa, S.; Zohny, S.F.; Swellam, M.; Mahmoud, M.H.; El-Zayat, T.M.; Salem, A.M. Comparison of CD44 and cytokeratin 20 mRNA in voided urine samples as diagnostic tools for bladder cancer. Clin. Biochem. 2008, 41, 1335–1341.

- Woodman, A.C.; Goodison, S.; Drake, M.; Noble, J.; Tarin, D. Noninvasive diagnosis of bladder carcinoma by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay detection of CD44 isoforms in exfoliated urothelia. Clin. Cancer Res. 2000, 6, 2381–2392.

- Smith, Z.L.; Guzzo, T.J. Urinary markers for bladder cancer. F1000Prime Rep. 2013, 5, 21.

- Yafi, F.A.; Brimo, F.; Steinberg, J.; Aprikian, A.G.; Tanguay, S.; Kassouf, W. Prospective analysis of sensitivity and specificity of urinary cytology and other urinary biomarkers for bladder cancer. Urol. Oncol. Semin. Orig. Investig. 2015, 33, 66.e25–66.e31.

- Chan, K.M.; Gleadle, J.M.; Li, J.Y.; Vasilev, K.; MacGregor, M. Shedding Light on Bladder Cancer Diagnosis in Urine. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 383.

- Kolodziejczyk, A.A.; Kim, J.K.; Svensson, V.; Marioni, J.C.; Teichmann, S.A. The Technology and Biology of Single-Cell RNA Sequencing. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 610–620.

- Winterhoff, B.J.; Maile, M.; Mitra, A.K.; Sebe, A.; Bazzaro, M.; Geller, M.A.; Abrahante, J.E.; Klein, M.; Hellweg, R.; Mullany, S.A.; et al. Single cell sequencing reveals heterogeneity within ovarian cancer epithelium and cancer associated stromal cells. Gynecol. Oncol. 2017, 144, 598–606.

- Cohen, S.J.; Punt, C.J.A.; Iannotti, N.; Saidman, B.H.; Sabbath, K.D.; Gabrail, N.Y.; Picus, J.; Morse, M.; Mitchell, E.; Miller, M.C.; et al. Relationship of Circulating Tumor Cells to Tumor Response, Progression-Free Survival, and Overall Survival in Patients With Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3213–3221.

- Cristofanilli, M.; Budd, G.T.; Ellis, M.J.; Stopeck, A.; Matera, J.; Miller, M.C.; Reuben, J.M.; Doyle, G.V.; Allard, W.J.; Terstappen, L.W.; et al. Circulating Tumor Cells, Disease Progression, and Survival in Metastatic Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 351, 781–791.

- De Bono, J.S.; Scher, H.I.; Montgomery, R.B.; Parker, C.; Miller, M.C.; Tissing, H.; Doyle, G.; Terstappen, L.W.; Pienta, K.J.; Raghavan, D. Circulating Tumor Cells Predict Survival Benefit from Treatment in Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008, 14, 6302–6309.

- Riethdorf, S.; Fritsche, H.; Müller, V.; Rau, T.; Schindlbeck, C.; Rack, B.; Janni, W.; Coith, C.; Beck, K.; Jänicke, F.; et al. Detection of Circulating Tumor Cells in Peripheral Blood of Patients with Metastatic Breast Cancer: A Validation Study of the CellSearch System. Clin. Cancer Res. 2007, 13, 920–928.

- Zhang, Z.; Fan, W.; Deng, Q.; Tang, S.; Wang, P.; Xu, P.; Wang, J.; Yu, M. The prognostic and diagnostic value of circulating tumor cells in bladder cancer and upper tract urothelial carcinoma: A meta-analysis of 30 published studies. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 59527–59538.

- Riethdorf, S.; Soave, A.; Rink, M. The current status and clinical value of circulating tumor cells and circulating cell-free tumor DNA in bladder cancer. Transl. Androl. Urol. 2017, 6, 1090–1110.

- Chen, A.; Fu, G.; Xu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Chen, X.; Cheng, K.S.; Neoh, K.H.; Tang, Z.; Chen, S.; Liu, M.; et al. Detection of Urothelial Bladder Carcinoma via Microfluidic Immunoassay and Single-Cell DNA Copy-Number Alteration Analysis of Captured Urinary-Exfoliated Tumor Cells. Cancer Res. 2018, 78, 4073–4085.

- Liang, L.-G.; Kong, M.-Q.; Zhou, S.; Sheng, Y.-F.; Wang, P.; Yu, T.; Inci, F.; Kuo, W.P.; Li, L.-J.; Demirci, U.; et al. An integrated double-filtration microfluidic device for isolation, enrichment and quantification of urinary extracellular vesicles for detection of bladder cancer. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep46224.

- Lv, S.; Yu, J.; Zhao, Y.; Li, H.; Zheng, F.; Liu, N.; Li, D.; Sun, X. A Microfluidic Detection System for Bladder Cancer Tumor Cells. Micromachines 2019, 10, 871.

- Eissa, S.; Habib, H.; Ali, E.; Kotb, Y. Evaluation of urinary miRNA-96 as a potential biomarker for bladder cancer diagnosis. Med. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1–7.

- Mengual, L.; Lozano, J.J.; Ingelmo-Torres, M.; Gazquez, C.; Ribal, M.J.; Alcaraz, A. Using microRNA profiling in urine samples to develop a non-invasive test for bladder cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2013, 133, 2631–2641.

- Urquidi, V.; Netherton, M.; Gomes-Giacoia, E.; Serie, D.J.; Eckel-Passow, J.; Rosser, C.J.; Goodison, S. A microRNA biomarker panel for the non-invasive detection of bladder cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 86290–86299.

- Zhang, D.-Z.; Lau, K.-M.; Chan, E.S.Y.; Wang, G.; Szeto, C.-C.; Wong, K.; Choy, R.K.W.; Ng, C.-F. Cell-Free Urinary MicroRNA-99a and MicroRNA-125b Are Diagnostic Markers for the Non-Invasive Screening of Bladder Cancer. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100793.

- Feber, A.; Dhami, P.; Dong, L.; De Winter, P.; Tan, W.S.; Martínez-Fernández, M.; Paul, D.S.; Hynes-Allen, A.; Rezaee, S.; Gurung, P.; et al. UroMark—a urinary biomarker assay for the detection of bladder cancer. Clin. Epigenetics 2017, 9, 8.

- Su, S.-F.; Abreu, A.L.D.C.; Chihara, Y.; Tsai, Y.; Andreu-Vieyra, C.; Daneshmand, S.; Skinner, E.C.; Jones, P.A.; Siegmund, K.; Liang, G. A Panel of Three Markers Hyper- and Hypomethylated in Urine Sediments Accurately Predicts Bladder Cancer Recurrence. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 1978–1989.

- Wang, Y.; Yu, Y.; Ye, R.; Zhang, D.; Li, Q.; An, D.; Fang, L.; Lin, Y.; Hou, Y.; Xu, A.; et al. An epigenetic biomarker combination of PCDH17 and POU4F2 detects bladder cancer accurately by methylation analyses of urine sediment DNA in Han Chinese. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 2754–2764.