Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 2 by Peter Tang and Version 1 by Marta Migocka-Patrzałek.

Glycogen phosphorylase (PG) is a key enzyme taking part in the first step of glycogenolysis. Muscle glycogen phosphorylase (PYGM) differs from other PG isoforms in expression pattern and biochemical properties. The main role of PYGM is providing sufficient energy for muscle contraction.

- PYGM

- muscle glycogen phosphorylase

- functional protein partners

- glycogenolysis

- McArdle disease

- cancer

- schizophrenia

1. Introduction

The main energy substrate in animal tissues is glucose, which is stored in the liver and muscles in the form of glycogen, a polymer consisting of glucose molecules. The molecules are connected via α-1,4-glycosidic and α-1,6-glycosidic bonds. Glycogen phosphorylase (GP) breaks α-1,4-glycosidic bonds, and the glucose-1-phosphate (G1P) molecule is released in the first step of glycogenolysis [1]. GP exists in three isoforms in the human body: phosphorylase, glycogen, liver (PYGL, UniProtKB no. P06737); phosphorylase, glycogen, brain (PYGB, no. P11216); and phosphorylase, glycogen, muscle (PYGM, no. P11217, commonly known as a muscle glycogen phosphorylase or myophosphorylase). The three isoforms differ in their physiological role and regulatory properties depending on the tissue in which they occur [2]. The PYGL, PYGB, and PYGM isoforms encoded by three distinct genes (on human chromosome 14q22, 20, and 11q13 respectively) share about 80% sequence identity at the protein level, and are structurally similar [3,4][3][4]. GP is a highly specialized enzyme, and its gene sequence is evolutionarily conserved. The comparative sequence analysis of phosphorylases shows that mammalian muscle and brain isoforms are more closely related to each other than to the liver form [5].

The metabolism, including glucose homeostasis, is linked to the circadian clock. The glycogen synthase (GS), glycogen phosphorylase, and glycogen level itself undergo regular changes in 24-h manner [6,7,8][6][7][8]. Despite that the GS and GP has an opposite functions, namely synthesis and sequestering of glycogen, their mRNA level is rising simultaneously at the morning phase in Neurospora crassa. The deletion of GP abolished the rhythmic GS gene expression, and glycogen accumulation. Regulation of GS and GP activity relies probably on allosteric changes and reversible phosphorylation. The GP is activated by phosphorylation, whereas phosphorylated GS is inactivated. This may result in the “switch like” system, in which one enzyme is active while the second is inactive [8]. The crucial role of clock-controlled glucose homeostasis and energy balance among mammals indicates that this mechanism may be evolutionarily conserved [6,7,9][6][7][9].

Additionally to their primary role in the first step of glycogenolysis, the GP isoforms also play a specific role in particular processes. The main function of PYGM and PYGB is their participation in adenosine triphosphate (ATP) production, gained from the glycogen deposits, to provide sufficient energy for biological processes in cells, such as contraction in the case of muscle. PYGL produces glucose molecules to maintain the glucose level in the bloodstream [5,10,11,12][5][10][11][12].

There are two mechanisms of GP activation: reversible phosphorylation and allosteric regulation. Allosteric regulation is understood as the balance between the T (tense, inactive) and R (relaxed, active) states, based on the conformational changes caused by the binding of regulatory molecules. The activators include adenosine monophosphate (AMP), inorganic phosphate (Pi), G1P, and glycogen, whereas inhibitors include ATP, glucose-6-phosphate (G6P), glucose, and purine [13]. PYGB and PYGM can be regulated by both serine phosphorylation and allosteric changes, but PYGL can only be regulated by reversible phosphorylation at serine 15 [4]. The difference between the biological role of PYGM and PYGB is based on their biochemical properties, particularly on the different affinity to AMP and glucose. When the level of AMP in the cell is low, PYGB reduces its enzymatic activity and does not respond to extracellular activation signals coming from the phosphorylation cascade. Therefore PYGB, present in fetal, brain, and heart tissue, is responsible for maintaining the optimal glycogen level for internal use. Indeed PYGB is responsible for providing an emergency energy source during periods of hypoxia, hypoglycemia, and ischemia [14,15][14][15]. On the other hand, PYGM is very active and responds to extracellular control via phosphorylation regardless of the cellular level of AMP. The mechanism of action results from its physiological role, which is a muscle contraction in response to neural and hormonal signals [16].

PYGM gains attention because of its crucial role in muscle functions and myopathies. Moreover, PYGM was found to be involved not only in glycogenolysis, but is also important in other physiological and pathological processes.

2. PYGM Expression in Different Tissues and Organs

PYGM mRNA expression analysis, based on transcriptomics datasets, shows that besides human skeletal muscles, it is also present in other tissues and organs. PYGM mRNA is present in organs containing skeletal muscle tissue, such as the tongue, glands, and esophagus. However, it is also detected e.g., in different parts of the brain, lymphoid tissues (tonsil), blood (granulocytes), salivary glands, male reproductive system, and adipose tissue [17]. PYGM and PYGB were shown to be colocalized in cardiomyocytes. Moreover, the heart-to-brain ratio of PYGM and PYGB protein and mRNA is similar, indicating that coexistence of the isoforms in heart muscle cells must be important for cardiac functions [18]. The tissue data for RNA expression obtained within one of the approaches, FANTOM5, reveal PYGM mRNA expression also in the eye (retina) [19].

The integrating quantitative transcriptomics performed on the human tissues, together with microarray-based immunohistochemistry, show that PYGM protein is expressed in the skeletal muscle tissue at a high level. At the same time, this analysis reveals that PYGM is also detectable in the cerebellum [17]. The antibody staining data confirm this finding and indicate that PYGM is present in the granular and white matter cells of the cerebellum, although its level is assessed as low. Glycogen muscle phosphorylase is the main form of GP expressed in glial cells in the human nervous system, specifically in astrocytes [20,21,22][20][21][22]. PYGM, identified by mass spectrometry, is also found in T lymphocytes, where it plays an important role in their immunological functions [23,24,25,26][23][24][25][26]. PYGM was also detected in the rat kidney homogenates, where it was localized in the interstitial cells of the cortex and outer medulla [27]. Additionally, the research data confirm the FANTOM5 results, showing that PYGM is expressed in the retinal pigment epithelium and cone photoreceptors [28,29][28][29].

The fact that PYGM is present not only in skeletal muscles, but also in several other tissues and organs, is probably due to its specific functions in these locations, probably connected with its biochemical properties.

3. The Biological Importance of PYGM

3.1. The Role of PYGM in Physiology

Muscle glycogen phosphorylase catalyzes the first step of glycogenolysis to meet the energy requirements for muscle activity. At the resting state, the inactive enzyme can be activated by AMP or inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP), and is inhibited by ATP, G1P, and other metabolites. The coenzymes important for PYGM enzymatic activity regulation are pyridoxal phosphate (PLP, the active form of vitamin B6) [30], and Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1 (Rac1) [23].

The datasets provided by Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG), the biological pathways database, confirm that PYGM is involved mainly in the starch and sucrose metabolism and metabolic pathways, but indicates its involvement also in the insulin and glucagon signaling pathway, insulin resistance, and necroptosis [31].

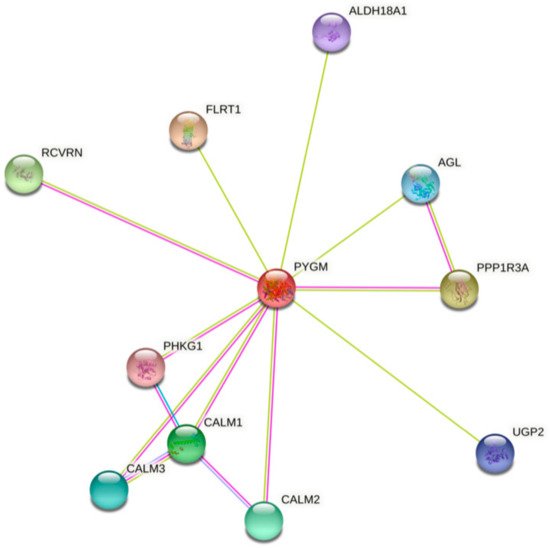

The analysis of bioinformatics resources using the STRING tool shows additional possible protein–protein interactions, which may be important for the PYGM functions (Figure 1) [32]. The predicted physical network of functional protein partners with PYGM includes proteins involved in glycogen metabolism, specifically in glycogen breakdown (glycogenolysis), such as phosphorylase b kinase (PHK) catalytic subunit (PHKG1), and its delta subunit—calmodulin (encoded by three genes, CALM1, CALM2, and CALM3). The analysis additionally indicates the interaction with glycogen debranching enzyme (amylo-alpha-1,6-glucosidase, AGL) via protein phosphatase 1 (PPP1). Some of the predicted interactions have been experimentally verified. The two-hybrid experiment shows the interaction between PYGM and PPP1R3B (protein phosphatase 1, regulatory subunit 3B) [33].

Figure 1. The human muscle glycogen phosphorylase (PYGM) protein–protein interaction network. The prediction, based on text mining, experiments, and databases, of possible PYGM associations. The edges indicate that the proteins are part of a physical complex. Four differently colored lines represent four types of evidence. A pink line indicates the experimentally determined interactions; light blue—database evidence; green—text mining evidence; dark blue—gene co-occurrence. ALDH18A1—aldehyde dehydrogenase 18 family member A1; AGL—amylo-alpha-1,6-glucosidase, 4-alpha-glucanotransferase; CALM1, 2, 3—calmodulin 1, 2, 3; FLRT1—fibronectin leucine rich transmembrane protein 1; PHKG1—phosphorylase kinase catalytic subunit gamma 1; PPP1R3A—protein phosphatase 1 regulatory subunit 3A; RCVRN—recoverin; UGP2—UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase 2. According to the Protein–Protein Interaction Networks Functional Enrichment Analysis, STRING (accessed on 4 February 2021) [32].

PYGM plays a role in insulin and glucagon signaling, and insulin resistance pathways involving regulation of the glycogen level. PYGM participates in these processes through PHK and CALM in the signaling, and through PPP1 in the insulin resistance pathways [31,32][31][32]. The kinase PHK mediates the neural and hormonal regulation of glycogen breakdown by phosphorylating and thereby activating muscle glycogen phosphorylase. The phosphatase PP1 participates e.g., in the regulation of glycogen metabolism, muscle contraction, and protein synthesis. AGL is a multifunctional enzyme acting as a glycosyltransferase and glucosidase in glycogen debranching. CALM1 mediates the control of a large number of enzymes, ion channels, aquaporins, and other proteins through calcium binding [34].

PYGM is also involved in the phototransduction pathway, the process in which the photoreceptor cells generate electrical signals in response to captured photons. Probably PYGM is involved in the inactivation, recovery, and/or regulation of the phototransduction cascade through interaction with recoverin (RCVRN) and CALM1, both connected with Ca2+ cellular level regulation. The RCVRN, a low-molecular-weight, neuronal calcium sensor, is involved in phototransduction cascade regulation and signal transmission in a calcium-dependent manner [32,35][32][35]. So far, no experimental data explain the exact role of PYGM in this process. However, it is known that retinopathy can be one of the symptoms in muscle glycogen phosphorylase deficiency (McArdle disease) [29,36,37,38][29][36][37][38]. Analysis of the PYGM expression pattern leads to the conclusion that impaired glycogen metabolism, both in the retinal pigment epithelium and in cone photoreceptors, is involved in McArdle disease-linked retinopathy [29].

The role of PYGM in necroptosis described in the KEGG database, a type of programmed cell death with necrotic morphology, is based on the interaction with receptor interacting serine/threonine kinase (RIPK). RIPK3 activates glycogen phosphorylase and therefore influences glycogenolysis [39,40][39][40].

PYGM was also shown to play an important role in regulating the immune function of T cells. The stimulation of T cells with interleukin 2 (IL-2) leads to the activation of a small GTPase of the RAS family, RAC1. In its active configuration, RAC1 binds to PYGM and modulates PYGM enzymatic activity, leading to T-cell migration and proliferation [23,25,26][23][25][26]. Llavero et al. (2019) propose an additional possible mechanism of this signal cascade. Their model assumes that the PYGM activation (through RAC1) may be controlled by the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [41].

The PYGM protein–protein interaction network and its involvement in the biological processes are probably much wider, i.e., the possibly conserved role of glycolysis in promoting myoblast fusion-based muscle growth [37]. The formation of syncytial muscles is probably founded on glycolysis-based high-rate biomass production. Indeed the attenuation of one of the genes involved in glycolysis, phosphoglycerate mutase 2 (Pglym78/pgam2), leads to the formation of thinner muscles in Drosophila melanogaster embryos [42]. The Pygm protein level was shown to increase during zebrafish (Danio rerio) development, which correlates with the decrease in glycogen level. At the same time, the Pygm distribution in zebrafish muscles changed from dispersed to highly organized. These events correspond to increased energy demand, due to the first movements of the developing embryo [43].

The assembly performed within the Biological General Repository for Interaction Datasets (BioGRID) public database revealed almost 50 proteins involved in the biological interactions with PYGM (see Table S1) [44]. Therefore, it is highly probable that PYGM is an important factor involved not only in glycogenolysis but also in a diverse range of other physiological and pathological biological processes.

3.2. The Role of PYGM in Pathological Processes

3.2.1. Muscle Glycogen Phosphorylase Deficiency (McArdle Disease)

Muscle glycogen phosphorylase deficiency (glycogen storage disorder type V called also McArdle disease; # 232600 in the Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM, database) is the most common disorder of the skeletal muscle carbohydrate [45]. McArdle disease is an autosomal recessive metabolic disorder, caused by a lack of muscle glycogen phosphorylase. The most frequent mutations leading to McArdle disease are p.R50X, p.G205S, and L542T. So far, 206 mutations in the PYGM gene leading to McArdle disease development have been described. These mutations affect the processing of PYGM mRNA, may cause the absence of enzymatic activity, disrupt the interaction between enzyme dimers, or cause the lack of substrate binding [45,46,47][45][46][47]. The severity of the disease is most probably connected with diverse mechanisms, including post-transcriptional events, epigenetics factors, or modification of protein function [48]. The lack of active enzyme leads to the inability to gain the energy from glycogen needed for skeletal muscle contraction. Patients suffer from the onset of exercise intolerance and muscle cramps. Myoglobinuria may occur after physical effort, due to rhabdomyolysis. In some cases severe myoglobinuria may lead to acute renal failure [4,45][4][45].

Several case reports and longitudinal case studies have confirmed that retinopathy is an additional clinical phenotype feature associated with McArdle disease [29,36,37,38,49][29][36][37][38][49]. In the case of McArdle patients, the lack of PYGM may impair the ability of retinal pigment epithelium and cone photoreceptors to obtain sufficient energy, which may further lead to pathological changes [29]. Human retinal pigment epithelium cells express both brain and muscle forms of glycogen phosphorylase [28]. However, the presence of PYGB in epithelial cells may not be sufficient for efficient energy metabolism.

3.2.2. PYGM in Schizophrenia

Disturbances in glutamate-mediated neurotransmission and alteration in energy metabolism in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) are observed in schizophrenia [22,50,51][22][50][51]. The glycogenolysis in neurons provides lactate as a transient energy supply. This source of energy is necessary for integrating the glutamatergic neurotransmission and glucose utilization processes. This mechanism could be altered in the disease and leads to an energy deficit. Pinacho et al. (2016) found that indeed the protein levels of PYGM and RAC1, a kinase that regulates PYGM activity, are reduced in the astrocytes in schizophrenia [22]. The interaction between PYGM and RAC1 in astrocytes may be similar to that described in the T cells [23,25,26][23][25][26]. The metabolic pathway in astrocytes, involving PYGM, could contribute to a transient local energy deficit in DLPFC in schizophrenia [22].

The equilibrium between brain and muscle isoform of glycogen phosphorylase in astrocytes may be controlled in a sex-dependent manner. It is because of the distinct astrocyte receptor profiles in males and females. The noradrenergic control over the astrocyte glycogen mobilization differs in the case of the adrenergic versus estrogen receptors. The exact mechanism needs further investigation, however authors conclude that glycogen turnover in the ventromedial hypothalamic nucleus, key structure responsible for the glucostatic control, is crucially important for maintaining brain functions. Therefore the future understanding of mechanism of noradrenergic control of glycogen level is an important issue [52]. Disturbances in glutamate-mediated neurotransmission have been observed not only in schizophrenia but also in various other neuropsychiatric disorders, including substance abuse, mood disorders, autism-spectrum disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease [53]. Therefore the regulation of glycogenolysis may be an important factor in the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases. Especially in regards to identify the potential therapeutic targets for neuro-protective stabilization of glycogen level in systemic glucose dysregulation states.

The relationship between McArdle disease and schizophrenia, if any, is so far elusive. However, the recent data coming from the European registry for patients with McArdle disease and other muscle glycogenoses (EUROMAC) report the mental disorders reaching 6.6% (16 in the cohort of 241 patients). One case of schizophrenia was indicated within this category [54].

3.2.3. PYGM in Cancer

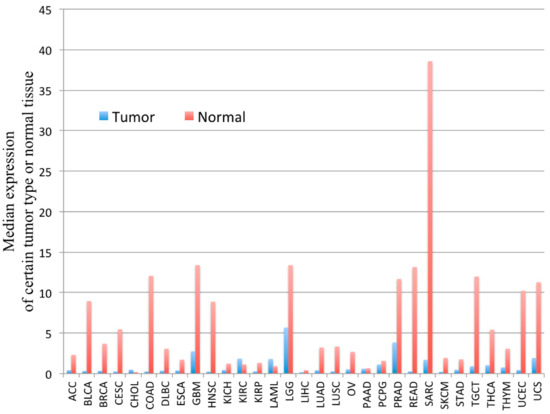

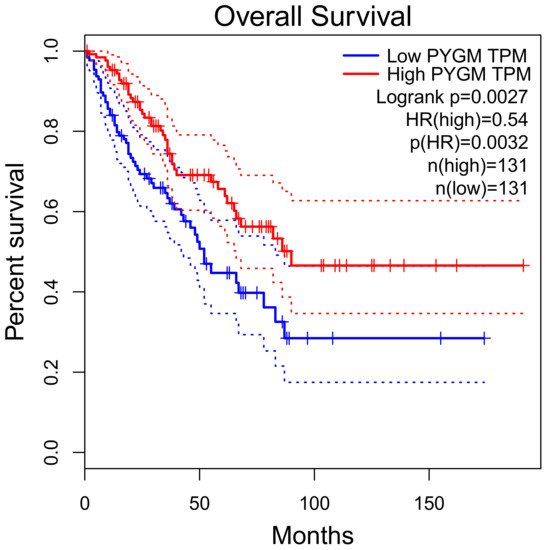

PYGM expression is down-regulated in cancer. According to the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA) of the RNA sequencing data, PYGM expression is lower in many types of cancer than in normal tissues (Figure 2). One of the largest differences is observed in the case of sarcoma (SARC), where PYGM expression is almost 20 times lower than in normal tissue. The analysis of data obtained from patients with SARC shows a significant difference in the survival rate between patients with low and high PYGM expression levels (Figure 3), indicating that PYGM may be a biomarker for SARC, and a useful parameter for disease prognosis [55]. Another example is the bioinformatics-based discovery indicating that PYGM and troponin C2, fast skeletal type (TNNC2), are significantly down-regulated in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. The bioinformatics analysis of RNA sequencing data, confirmed experimentally, shows that both PYGM and TNNC2 could be potentially used as therapeutics or biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis in this type of cancer [56]. Interestingly, the expression of TNNC1 and TNNC2 genes was also shown to be significantly down-regulated in the case of PYGM deficiency (McArdle) disease [57].

Figure 2. The PYGM gene expression profile across tumor samples and corresponding normal tissues. The height of the bar represents the median expression of a certain tumor type (blue) or normal tissue (red). ACC—adrenocortical carcinoma, BLCA—bladder urothelial carcinoma, BRCA—breast invasive carcinoma, CESC—cervical squamous cell carcinoma and endocervical adenocarcinoma, CHOL—cholangiocarcinoma, COAD—colon adenocarcinoma, DLBC—lymphoid neoplasm diffuse large b-cell lymphoma, ESCA—esophageal carcinoma, GBM—glioblastoma multiforme, HNSC—head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, KICH—kidney chromophobe, KIRC—kidney renal clear cell carcinoma, KIRP—kidney renal papillary cell carcinoma, LAML—acute myeloid leukemia, LGG—brain lower grade glioma, LIHC—liver hepatocellular carcinoma, LUAD—lung adenocarcinoma, LUSC—lung squamous cell carcinoma, MESO—mesothelioma, OV—ovarian serous cystadenocarcinoma, PAAD—pancreatic adenocarcinoma, PCPG—pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma, PRAD—prostate adenocarcinoma, READ—rectum adenocarcinoma, SARC—sarcoma, SKCM—skin cutaneous melanoma, STAD—stomach adenocarcinoma, TGCT—testicular germ cell tumors, THCA—thyroid carcinoma, THYM—thymoma, UCEC—uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma, UCS—uterine carcinosarcoma, UVM—uveal melanoma. According to the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, GEPIA, on-line tool www.gepia.cancer (accessed on 4 February 2021) [55].

Figure 3. Overall survival rate of patients with sarcoma, depending on the PYGM gene expression rate. Low (median) PYGM expression correlated with poorer survival. Normalized RNA-sequencing data as transcripts per million (TPM). HR—hazard ratio calculated using Cox PH Model. The solid line represents the survival curve and the dotted line represents the 95% confidence interval. According to the Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis, GEPIA, available online www.gepia.cancer (accessed on 4 February 2021) [55].

Next-generation sequencing applied to three different subtypes of rare aggressive breast cancers (metaplastic, micropapillary, and pleomorphic lobular breast cancer) showed a 30% mutation rate in the PYGM gene. The missense mutation, similar in location to those identified in McArdle disease, probably leads to a loss-of-function effect, which could be one of the pathological mechanisms of cancer development. Immunohistochemical analysis confirmed lower PYGM expression in the tumor area when compared to non-malignant tissue surrounding tumor cells [58].

Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) is a cancer syndrome, inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with high penetrance. MEN1 patients suffer from the development of a variety of tumors, such as parathyroids, endocrine pancreas, and anterior pituitary [59,60][59][60]. Interestingly, the MEN1 gene was found to be tightly linked to PYGM on the 11q13 chromosome. MEN1 is located less than 100 kb telomeric to PYGM [61]. The correlation between MEN1 and PYGM is worth noting, because the losses of heterozygosity regarding the 11q13 chromosome are often observed not only in MEN1 but also in the case of sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung and invasive breast cancers [62,63,64,65,66][62][63][64][65][66]. It is also known that the 11q13 chromosome rearrangements play an important role in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (B-NHL) [67].

On the other hand, Pastor et al. (2013) observed up-regulation of the PYGM protein in samples obtained from patients with lung cancer. The results revealed that PYGM protein and other proteins involved in the regulation of glycolysis, such as transketolase (TKT), fructose-bisphosphatase 1 (FBP1), aldolase fructose-bisphosphate A (ALDOA), and pyruvate kinase M1/2 (PKM2), were up-regulated in that set of experiments [68]. There are several possible explanations why the results differ from those previously reported, such as specificity of the patient group (15 males, mainly smokers), or a particular type of cancer with a distinct molecular mechanism [68].

In summary, the RNA sequencing results from public databases as well as the experimental data from different research indicates that PYGM could be an important factor in cancer development and progression. In the group of 241 McArdle disease and other muscle glycogenoses patients, the 4.6% cases of cancer were identified [54]. The glycogen metabolism plays a key role in tumorigenesis. Not only PYGM, but also PYGB level is up-regulated in different kinds of cancer such as colorectal cancer [69], hepatocellular carcinoma [70], prostate cancer [71], non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [72], and ovarian cancer [73]. However, one should keep in mind that carcinogenesis is a complex process in which many factors interact together [74]. Therefore, the exact role of PYGM and other GPs in this process needs further study.

References

- Di Mauro, S. Muscle glycogenoses: An overview. Acta Myol. 2007, 26, 35–41.

- Nogales-Gadea, G.; Santalla, A.; Brull, A.; De Luna, N.; Lucia, A.; Pinós, T. The pathogenomics of McArdle disease—Genes, enzymes, models, and therapeutic implications. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2015, 38, 221–230.

- Freeman, S.; Bartlett, J.B.; Convey, G.; Hardern, I.; Teague, J.L.; Loxham, S.J.G.; Allen, J.M.; Poucher, S.M.; Charles, A.D. Sensitivity of glycogen phosphorylase isoforms to indole site inhibitors is markedly dependent on the activation state of the enzyme. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 149, 775–785.

- Llavero, F.; Sastre, A.A.; Montoro, M.L.; Gálvez, P.; Lacerda, H.M.; Parada, L.A.; Zugaza, J.L. McArdle Disease: New Insights into Its Underlying Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5919.

- Hudson, J.W.; Golding, G.; Crerar, M.M. Evolution of Allosteric Control in Glycogen Phosphorylase. J. Mol. Biol. 1993, 234, 700–721.

- Turek, F.W.; Joshu, C.; Kohsaka, A.; Lin, E.; Ivanova, G.; McDearmon, E.; Laposky, A.; Losee-Olson, S.; Easton, A.; Jensen, D.R.; et al. Obesity and Metabolic Syndrome in Circadian Clock Mutant Mice. Science 2005, 308, 1043–1045.

- Stenvers, D.J.; Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Schrauwen, P.; La Fleur, S.E.; Kalsbeek, A. Circadian clocks and insulin resistance. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2019, 15, 75–89.

- Baek, M.; Virgilio, S.; Lamb, T.M.; Ibarra, O.; Andrade, J.M.; Gonçalves, R.D.; Dovzhenok, A.; Lim, S.; Bell-Pedersen, D.; Bertolini, M.C.; et al. Circadian clock regulation of the glycogen synthase (GSN) gene by WCC is critical for rhythmic glycogen metabolism inNeurospora crassa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 10435–10440.

- Scheer, F.A.J.L.; Hilton, M.F.; Mantzoros, C.S.; Shea, S.A. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 4453–4458.

- Chasiotis, D. The regulation of glycogen phosphorylase and glycogen breakdown in human skeletal muscle. Acta Physiol. Scand. Suppl. 1983, 518, 1–68.

- Hue, L.; Bontemps, F.; Hers, H. The effects of glucose and of potassium ions on the interconversion of the two forms of glycogen phosphorylase and of glycogen synthetase in isolated rat liver preparations. Biochem. J. 1975, 152, 105–114.

- Ding, Y.-J.; Li, G.-Y.; Xu, C.-D.; Wu, Y.; Zhou, Z.-S.; Wang, S.-G.; Li, C. Regulatory Functions of Nilaparvata lugens GSK-3 in Energy and Chitin Metabolism. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 518876.

- Madsen, N.B.; Avramovic-Zikic, O.; Honikel, K.O. Structure-Function Relationships in Glycogen Phosphorylase with Respect to Its Control Characteristics. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1973, 210, 222–237.

- Lillpopp, L.; Tzikas, S.; Ojeda, F.; Zeller, T.; Baldus, S.; Bickel, C.; Sinning, C.R.; Wild, P.S.; Genth-Zotz, S.; Warnholtz, A.; et al. Prognostic Information of Glycogen Phosphorylase Isoenzyme BB in Patients with Suspected Acute Coronary Syndrome. Am. J. Cardiol. 2012, 110, 1225–1230.

- Pudil, R.; Vašatová, M.; Lenco, J.; Tichy, M.; Řeháček, V.; Fucikova, A.; Horacek, J.M.; Vojacek, J.; Pleskot, M.; Stulik, J.; et al. Plasma glycogen phosphorylase BB is associated with pulmonary artery wedge pressure and left ventricle mass index in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2010, 48, 1193–1195.

- Crerar, M.M.; Karlsson, O.; Fletterick, R.J.; Hwang, P.K. Chimeric Muscle and Brain Glycogen Phosphorylases Define Protein Domains Governing Isozyme-specific Responses to Allosteric Activation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 13748–13756.

- Uhlén, M.; Fagerberg, L.; Hallström, B.M.; Lindskog, C.; Oksvold, P.; Mardinoglu, A.; Sivertsson, Å.; Kampf, C.; Sjöstedt, E.; Asplund, A.; et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science 2015, 347, 1260419.

- Schmid, H.; Pfeiffer-Guglielmi, B.; Dolderer, B.; Thiess, U.; Verleysdonk, S.; Hamprecht, B. Expression of the Brain and Muscle Isoforms of Glycogen Phosphorylase in Rat Heart. Neurochem. Res. 2009, 34, 581–586.

- Abugessaisa, I.; Noguchi, S.; Hasegawa, A.; Harshbarger, J.; Kondo, A.; Lizio, M.; Severin, J.; Carninci, P.; Kawaji, H.; Kasukawa, T. FANTOM5 CAGE profiles of human and mouse reprocessed for GRCh38 and GRCm38 genome assemblies. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170107.

- Jakobsen, E.; Bak, L.K.; Walls, A.B.; Reuschlein, A.-K.; Schousboe, A.; Waagepetersen, H.S. Glycogen Shunt Activity and Glycolytic Supercompensation in Astrocytes May Be Distinctly Mediated via the Muscle form of Glycogen Phosphorylase. Neurochem. Res. 2017, 89, 537–2494.

- Pfeiffer-Guglielmi, B.; Fleckenstein, B.; Jung, G.; Hamprecht, B. Immunocytochemical localization of glycogen phosphorylase isozymes in rat nervous tissues by using isozyme-specific antibodies. J. Neurochem. 2003, 85, 73–81.

- Pinacho, R.; Vila, E.; Prades, R.; Tarragó, T.; Castro, E.; Ferrer, I.; Ramos, B. The glial phosphorylase of glycogen isoform is reduced in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in chronic schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2016, 177, 37–43.

- Arrizabalaga, O.; Lacerda, H.M.; Zubiaga, A.M.; Zugaza, J.L. Rac1 Protein Regulates Glycogen Phosphorylase Activation and Controls Interleukin (IL)-2-dependent T Cell Proliferation. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11878–11890.

- De Luna, N.; Brull, A.; Lucia, A.; Santalla, A.; Garatachea, N.; Martí, R.; Andreu, A.L.; Pinós, T. PYGM expression analysis in white blood cells: A complementary tool for diagnosing McArdle disease? Neuromuscul. Disord. 2014, 24, 1079–1086.

- Llavero, F.; Urzelai, B.; Osinalde, N.; Gálvez, P.; Lacerda, H.M.; Parada, L.A.; Zugaza, J.L. Guanine Nucleotide Exchange Factor αPIX Leads to Activation of the Rac 1 GTPase/Glycogen Phosphorylase Pathway in Interleukin (IL)-2-stimulated T Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 9171–9182.

- Llavero, F.; Artaso, A.; Lacerda, H.M.; Parada, L.A.; Zugaza, J.L. Lck/PLCγ control migration and proliferation of interleukin (IL)-2-stimulated T cells via the Rac1 GTPase/glycogen phosphorylase pathway. Cell. Signal. 2016, 28, 1713–1724.

- Schmid, H.; Dolderer, B.; Thiess, U.; Verleysdonk, S.; Hamprecht, B. Renal Expression of the Brain and Muscle Isoforms of Glycogen Phosphorylase in Different Cell Types. Neurochem. Res. 2008, 33, 2575–2582.

- Hernández, C.; Garcia-Ramírez, M.; García-Rocha, M.; Saez-López, C.; Valverde, Á.M.; Guinovart, J.J.; Simó, R. Glycogen storage in the human retinal pigment epithelium: A comparative study of diabetic and non-diabetic donors. Acta Diabetol. 2014, 51, 543–552.

- Vaclavik, V.; Naderi, F.; Schaller, A.; Escher, P. Longitudinal case study and phenotypic multimodal characterization of McArdle disease-linked retinopathy: Insight into pathomechanisms. Ophthalmic Genet. 2020, 41, 73–78.

- Johnson, L.N. Glycogen phosphorylase: Control by phosphorylation and allosteric effectors. FASEB J. 1992, 6, 2274–2282.

- Kanehisa, M.; Goto, S.; Furumichi, M.; Tanabe, M.; Hirakawa, M. KEGG for representation and analysis of molecular networks involving diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, D355–D360.

- Szklarczyk, D.; Gable, A.L.; Lyon, D.; Junge, A.; Wyder, S.; Huerta-Cepas, J.; Simonovic, M.; Doncheva, N.T.; Morris, J.H.; Bork, P.; et al. STRING v11: Protein–protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D607–D613.

- Blandin, G.; Marchand, S.; Charton, K.; Danièle, N.; Gicquel, E.; Boucheteil, J.-B.; Bentaib, A.; Barrault, L.; Stockholm, D.; Bartoli, M.; et al. A human skeletal muscle interactome centered on proteins involved in muscular dystrophies: LGMD interactome. Skelet. Muscle 2013, 3, 3.

- Adeva-Andany, M.M.; González-Lucán, M.; Donapetry-García, C.; Fernández-Fernández, C.; Ameneiros-Rodríguez, E. Glycogen metabolism in humans. BBA Clin. 2016, 5, 85–100.

- Zang, J.; Neuhauss, S.C.F. The Binding Properties and Physiological Functions of Recoverin. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2018, 11, 473.

- Alsberge, J.B.; Chen, J.J.; Zaidi, A.A.; Fu, A.D. Retinal Dystrophy in a Patient with Mcardle Disease. Retin. Cases Brief. Rep. 2018.

- Leonardy, N.J.; Harbin, R.L.; Sternberg, P. Pattern Dystrophy of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium in a Patient with McArdle’s Disease. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 1988, 106, 741–742.

- Mahroo, O.A.; Khan, K.N.; Wright, G.; Ockrim, Z.; Scalco, R.S.; Robson, A.G.; Tufail, A.; Michaelides, M.; Quinlivan, R.; Webster, A.R. Retinopathy Associated with Biallelic Mutations in PYGM (McArdle Disease). Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 320–322.

- Liu, Y.; Liu, T.; Lei, T.; Zhang, D.; Du, S.; Girani, L.; Qi, D.; Lin, C.; Tong, R.; Wang, Y. RIP1/RIP3-regulated necroptosis as a target for multifaceted disease therapy (Review). Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019, 44, 771–786.

- Zhang, D.-W.; Shao, J.; Lin, J.; Zhang, N.; Lu, B.-J.; Lin, S.-C.; Dong, M.-Q.; Han, J. RIP3, an Energy Metabolism Regulator That Switches TNF-Induced Cell Death from Apoptosis to Necrosis. Science 2009, 325, 332–336.

- Llavero, F.; Montoro, M.L.; Sastre, A.A.; Fernández-Moreno, D.; Lacerda, H.M.; Parada, L.A.; Lucia, A.; Zugaza, J.L. Epidermal growth factor receptor controls glycogen phosphorylase in T cells through small GTPases of the RAS family. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 4345–4358.

- Tixier, V.; Bataillé, L.; Etard, C.; Jagla, T.; Weger, M.; Daponte, J.P.; Strähle, U.; Dickmeis, T.; Jagla, K. Glycolysis supports embryonic muscle growth by promoting myoblast fusion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 18982–18987.

- Migocka-Patrzałek, M.; Lewicka, A.; Elias, M.; Daczewska, M. The effect of muscle glycogen phosphorylase (Pygm) knockdown on zebrafish morphology. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2020, 118, 105658.

- Stark, C.; Breitkreutz, B.J.; Reguly, T.; Boucher, L.; Breitkreutz, A.; Tyers, M. BioGRID: A general repository for interaction datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006, 34, D535–D539.

- Almodóvar-Payá, A.; Villarreal-Salazar, M.; De Luna, N.; Nogales-Gadea, G.; Real-Martínez, A.; Andreu, A.L.; Martín, M.A.; Arenas, J.; Lucia, A.; Vissing, J.; et al. Preclinical Research in Glycogen Storage Diseases: A Comprehensive Review of Current Animal Models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9621.

- Nogales-Gadea, G.; Brull, A.; Santalla, A.; Andreu, A.L.; Arenas, J.; Martín, M.A.; Lucia, A.; De Luna, N.; Pinós, T. McArdle Disease: Update of Reported Mutations and Polymorphisms in thePYGMGene. Hum. Mutat. 2015, 36, 669–678.

- Nogales-Gadea, G.; Pinós, T.; Lucia, A.; Arenas, J.; Cámara, Y.; Brull, A.; De Luna, N.; Martín, M.A.; Garcia-Arumí, E.; Marti, R.; et al. Knock-in mice for the R50X mutation in the PYGM gene present with McArdle disease. Brain 2012, 135, 2048–2057.

- Carvalho, A.A.S.; Christofolini, D.M.; Perez, M.M.; Alves, B.C.A.; Rodart, I.; Figueiredo, F.W.S.; Turke, K.C.; Feder, D.; Junior, M.C.F.; Nucci, A.M.; et al. PYGM mRNA expression in McArdle disease: Demographic, clinical, morphological and genetic features. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236597.

- Casalino, G.; Chan, W.; McAvoy, C.; Coppola, M.; Bandello, F.; Bird, A.C.; Chakravarthy, U. Multimodal imaging of posterior ocular involvement in McArdle’s disease. Clin. Exp. Optom. 2018, 101, 412–415.

- Sears, S.M.; Hewett, S.J. Influence of glutamate and GABA transport on brain excitatory/inhibitory balance. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021.

- Uno, Y.; Coyle, J.T. Glutamate hypothesis in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 73, 204–215.

- Briski, K.P.; Ibrahim, M.M.H.; Mahmood, A.S.M.H.; Alshamrani, A.A. Norepinephrine Regulation of Ventromedial Hypothalamic Nucleus Astrocyte Glycogen Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 759.

- Moghaddam, B.; Javitt, D.C. From Revolution to Evolution: The Glutamate Hypothesis of Schizophrenia and its Implication for Treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 2011, 37, 4–15.

- Scalco, R.S.; EUROMAC Consortium; Lucia, A.; Santalla, A.; Martinuzzi, A.; Vavla, M.; Reni, G.; Toscano, A.; Musumeci, O.; Voermans, N.C.; et al. Data from the European registry for patients with McArdle disease and other muscle glycogenoses (EUROMAC). Orphanet. J. Rare Dis. 2020, 15, 1–8.

- Tang, Z.; Li, C.; Kang, B.; Gao, G.; Li, C.; Zhang, Z. GEPIA: A web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, W98–W102.

- Jin, Y.; Yang, Y. Bioinformatics-based discovery of PYGM and TNNC2 as potential biomarkers of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Biosci. Rep. 2019, 39, 20191612.

- Nogales-Gadea, G.; Consuegra-García, I.; Rubio, J.C.; Arenas, J.; Cuadros, M.; Camara, Y.; Torres-Torronteras, J.; Fiuza-Luces, C.; Lucia, A.; Martín, M.A.; et al. A Transcriptomic Approach to Search for Novel Phenotypic Regulators in McArdle Disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31718.

- Dieci, M.V.; Smutná, V.; Scott, V.; Yin, G.; Xu, R.; Vielh, P.; Mathieu, M.-C.; Vicier, C.; Laporte, M.; Drusch, F.; et al. Whole exome sequencing of rare aggressive breast cancer histologies. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2016, 156, 21–32.

- Al-Salameh, A.; Baudry, C.; Cohen, R. Update on multiple endocrine neoplasia Type 1 and 2. La Presse Médicale 2018, 47, 722–731.

- Kedra, D.; Seroussi, E.; Fransson, I.; Trifunovic, J.; Clark, M.; Lagercrantz, J.; Blennow, E.; Mehlin, H.; Dumanski, J. The germinal center kinase gene and a novel CDC25-like gene are located in the vicinity of the PYGM gene on 11q13. Qual. Life Res. 1997, 100, 611–619.

- Lemmes, I.; Van de Ven, W.J.M.; Kas, K.; Zhang, C.X.; Giraud, S.; Wautot, V.; Buisson, N.; Pugeat, M.; Peix, J.L.; Caldener, A.; et al. The search for the MEN1 gene. The European Consortium on MEN-1. Intern. Med. 1998, 243, 441–446.

- Asteria, C.; Anagni, M.; Persani, L.; Beck-Peccoz, P. Loss of heterozygosity of the MEN1 gene in a large series of TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2001, 24, 796–801.

- Bièche, I.; Lidereau, R. Genetic alterations in breast cancer. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 1995, 14, 227–251.

- Debelenko, L.V.; Brambilla, E.; Agarwal, S.K.; Swalwell, J.I.; Kester, M.B.; Lubensky, I.A.; Zhuang, Z.; Guru, S.C.; Manickam, P.; Olufemi, S.-E.; et al. Identification of MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997, 6, 2285–2290.

- Petzmann, S.; Ullmann, R.; Klemen, H.; Renner, H.; Popper, H.H. Loss of heterozygosity on chromosome arm 11q in lung carcinoids. Hum. Pathol. 2001, 32, 333–338.

- Zhuang, Z.; Merino, M.J.; Chuaqui, R.; Liotta, L.; Emmert-Buck, M.R. Identical allelic loss on chromosome 11q13 in microdissected in situ and invasive human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 1995, 55, 467–471.

- Vandenberghe, E.; Peeters, C.D.W.; Wlodarska, I.; Stul, M.; Louwagie, A.; Verhoef, G.; Thomas, J.; Criel, A.; Cassiman, J.J.; Mecucci, C.; et al. Chromosome 11q rearrangements in B non Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br. J. Haematol. 1992, 81, 212–217.

- Pastor, M.; Nogal, A.; Molina-Pinelo, S.; Melendez, R.; Salinas, A.; De La Peña, M.G.; Martín-Juan, J.; Corral, J.; Garcia-Carbonero, R.; Carnero, A.; et al. Identification of proteomic signatures associated with lung cancer and COPD. J. Proteom. 2013, 89, 227–237.

- Tashima, S.; Shimada, S.; Yamaguchi, K.; Tsuruta, J.; Ogawa, M. Expression of brain-type glycogen phosphorylase is a potentially novel early biomarker in the carcinogenesis of human colorectal carcinomas. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2000, 95, 255–263.

- Cui, G.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Xing, J.; Song, W.; Zeng, Z.; Liu, L.; Wang, H.; Wang, X.; Luo, H.; et al. Glycogen Phosphorylase B Is Regulated by miR101-3p and Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Tumorigenesis. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 566494.

- Wang, Z.; Han, G.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, W.; Wang, J. Silencing of PYGB suppresses growth and promotes the apoptosis of prostate cancer cells via the NF-κB/Nrf2 signaling pathway. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 18, 3800–3808.

- Lee, M.K.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kang, C.D.; Kim, Y.D.; Choi, K.U.; Kim, H.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Park, D.Y.; et al. Clinicopathological significance of BGP expression in non-small-cell lung carcinoma: Relationship with histological type, microvessel density and patients’ survival. Pathology 2006, 38, 555–560.

- Zhou, Y.; Jin, Z.; Wang, C. Glycogen phosphorylase B promotes ovarian cancer progression via Wnt/β-catenin signaling and is regulated by miR-133a-3p. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 120, 109449.

- Davis, A.; Gao, R.; Navin, N. Tumor evolution: Linear, branching, neutral or punctuated? Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Bioenerg. 2017, 1867, 151–161.

More