Immunotherapy is promising in treating TNBCs.

- triple negative

- breast cancer

- mesenchymal subtype

- immunotherapy

- target therapy

1. Introduction

The management of breast cancer (BC), the most common tumor in women [1] has improved since its sub-classification based on the expression of estrogen (ER), progesterone receptors (PR) [2] and human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 (HER2) [3]. Four main molecular subtypes of BC have been identified so far, based on the analysis of its global gene expression: Luminal A, luminal B, HER2, basal-like, and the more recently identified claudin-low tumor subtype [4,5][4][5].

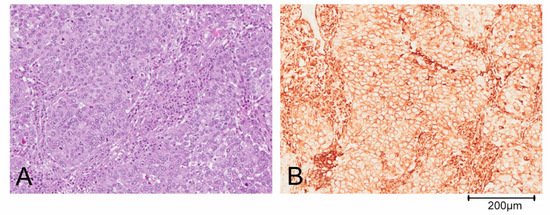

Triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) is defined by the lack of expression of ER, PR and HER2 and accounts for about 10–20% of BCs [6]. This definition of TNBC is, however, limiting and does not allow for understanding its heterogeneous clinical behavior. Based on gene expression profiling, TNBCs were originally divided by Lehmann into six different subtypes: Basal-like 1 (BL1), basal-like 2 (BL2), immunomodulatory (IM), mesenchymal-like (M), mesenchymal stem cell-like (MSL) and luminal androgen receptor (LAR). Both M and MSL subtypes express genes involved in the epithelial to mesenchymal transition (ETM), stromal interaction and cell motility. Moreover, the M subgroup displays a higher expression of genes involved in proliferation, while the MSL more frequently shows expression of genes associated with cell stemness [5,7][5][7]. Further studies revealed that the IM and MSL subtypes were strongly influenced by the contribution of transcripts from normal stroma and immune cells of the tumor microenvironment, respectively. Thus, the classification has been refined in the following 4 subtypes: BL1, BL2, M and LAR [7,8,9][7][8][9]. The complexity of the TNBC classification is also determined by the possibility of identification of more than one subgroup in some histological types: For example, metaplastic breast carcinoma could belong to either the BL2 or the M subtype of BCs. Predominantly, metaplastic tumor cells are pleomorphic and arranged in solid nests (Figure 1A). The epithelial cells shows a diffuse positivity for the mesenchymal marker vimentin on immunohistochemical staining (Figure 1B).

For the last two decades chemotherapy has been the only therapeutic option, in the absence of a druggable target. It played a central role in the treatment of TNBC in all disease settings, even though each TNBC subtype has a different response pattern to the available chemotherapy regimens [10]. Gene expression analysis may also influence chemotherapy treatment choices; a randomized phase III trial was performed comparing use of carboplatin vs. docetaxel in unselected advanced TNBC and in a priori specified biomarker defined sub-populations [11]. In the unselected TNBC patient population, carboplatin was not more active compared to docetaxel (the standard of care). Furthermore, there was no evidence that basal-like biomarkers could be predictive of higher response to platinum. Conversely, in patients with breast cancer gene (BRCA) mutation, likely to have targetable defects in DNA repair, treatment with carboplatin doubled the response rate. Finally, the response to docetaxel was significantly better than the one to carboplatin in patients with non-basal-like TNBCs. Unfortunately, such poor platinum response results were not further stratified into M and LAR subtypes, given that the first one is known to be chemoresistant while the latter being responsive to anti androgenic hormone treatment. Targeted therapies have recently expanded the options for treatment, offering the potential for a dramatic change in clinical practice. Such is the case with Poli ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors in BRCA-mutated breast cancer [12[12][13],13], serine/threonine protein kinase (AKT) inhibitors in phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase (PI3K)/AKT/Phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN)-altered TNBC [14[14][15],15], and trophoblast cell surface antigen-2 (Trop-2) directed antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) sacituzumab govitecan in heavily pre-treated TNBC [16].

The immune cell profiling highlights that each TNBC subtype showed a correlation to an immunomodulatory pattern, with the exception of the M subgroup in which no immune infiltrate was shown, and which is characterized by an immunosuppressive microenvironment [17]. The immune suppression can influence the response to treatment in all settings [18,19,20][18][19][20]. The cold status of the M phenotype is extremely important in light of the results achieved with immunotherapy in TNBCs. As a matter of fact, immunotherapy has recently shown a significant impact on progression free survival (PFS) in association with chemotherapy in inoperable or metastatic TNBC [21].

2. Immune System and Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is promising in treating TNBCs. However, not all TNBCs are equally susceptible, nor do they have the same immunological features. As previously mentioned, in the M subtype, the immune-escape mechanism could be predominant (Table 2). Consequently, in this subgroup, the best strategy could be to revert a non-responsive tumor to a responsive one through the combination of immunotherapy with other agents. A combination of atezolizumab with nab-paclitaxel prolonged PFS in a recent phase III trial [97][22]. In the treatment group, median PFS was 7.2 months (95% CI 5.6–7.4) with atezolizumab and 5.5 months (5.3–5.6) with placebo (HR 0.80 [95% CI 0.69–0.92, p = 0.0021]). In the PD-L1 positive population, the median PFS was significantly longer in the atezolizumab group (7.5 months) than in the placebo group (5.3 months, HR 0.63, p < 0.0001). No difference in PFS was reported in the PD-L1 negative subgroup. The final exploratory analysis showed an increased OS in PD-L1 positive subgroup (25 vs. 18 months, HR 0.71). Median OS was 21.0 months with atezolizumab and 18.7 months with placebo (HR 0.86, p = 0.078) [98][23].

Data from the phase Ib KEYNOTE 173 trial suggest that the association of the anti PD-1 pembrolizumab and different chemotherapy schedules is effective in neoadjuvant setting in locally advanced TNBCs, with an overall pCR of 60%, an ORR from 70% to 100% and a manageable safety profile [99][24]. In a recent phase III trial, the addition of pembrolizumab to the standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy increased the pCR rate from 51.2% in the placebo arm to 64.8% in the combination arm (p < 0.001). Moreover, after a median follow-up of 15.5 months, 7.4% in the pembrolizumab group and 11.8% in the placebo group had local or distant recurrence or passed away (HR 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.93). The efficacy of pembrolizumab in combination with chemotherapy in metastatic TNBC was also evaluated in the phase 3 trial KEYNOTE 355. In this study, patients were stratified according to PD-L1 status (combined positive score [CPS] < 1 or ≥1), previous treatment received, chemotherapy backbone (carboplatin plus gemcitabine or taxanes) but not according to the molecular subtype of TNBC. In patients with CPS of 10 or more, median PFS was 9.7 months in the treatment group and 5.6 months in the control one (HR 0.65, p = 0.0012). PFS rate at 12 months was significantly higher in the pembrolizumab group than in the placebo group (39.1% vs. 23.0%). There was no significant difference in PFS between treatments in patients with CPS ≥ 1 (7.6 vs. 5.6 months, HR 0.74, one-sided p = 0.0014); prespecified statistical criterion of alpha = 0.00111. However, the rate of PFS at 12 months in patients with CPS ≥ 1 was higher in the combination group than in the chemotherapy group (31.7% vs. 19.4%). No difference in PFS was achieved in patients with PD-L1 CPS < 1 (median PFS 6.3 months in the pembrolizumab–chemotherapy group and 6.2 months in the placebo–chemotherapy group; HR 1.08) [100][25]. Finally, the efficacy of durvalumab, another anti PD-L1 agent, was evaluated in neoadjuvant setting both in combination with chemotherapy or alone in a window-phase pre neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT). No statistical difference in pCR rate was seen between durvalumab group and placebo group (53.4% vs. 44.2%, OR = 1.45, unadjusted Wald p = 0.224). However, pCR rate was significantly higher in the window-phase group who received durvalumab alone before starting chemotherapy (61.0% vs. 41.4%, OR = 2.22, 95%, p = 0.035) [101][26].

These results highlight the role of immunotherapy in both metastatic and neoadjuvant setting as an additional strategy in TNBC and the role of PD-L1 as a predictive biomarker. However anti PD-1 agents, either alone or in combination with chemotherapy, seem to be ineffective in PD-L1 negative patients, as a result of a primary resistance that could be at least partly explained by the presence of mesenchymal transition. Furthermore, even in highly selected PD-L1 positive population, about 70% of patients will experience a progression of disease in the first 12 months. Further in-depth genomic investigations are required to understand and overcome resistance mechanisms. As an example, preliminary results from the IMpassion 131 trial are in contrast to those of previous studies, with no benefit in clinical outcomes from a combination of atezolizumab plus weekly paclitaxel vs. weekly paclitaxel alone [102][27]. PFS was not significantly improved by the combination of drugs vs. chemotherapy alone in either the PD-L1–positive (6.0 vs. 5.7 months; HR = 0.82; p = 0.20) or in the intention-to-treat population (5.7 vs. 5.6 months; HR 0.86; significance not formally tested). No subgroup had an additional benefit from the addition of anti PD-L1. Moreover, the combination did not improve OS in the PD-L1–positive group (22.1 vs. 28.3 months; HR 1.12).

A different distribution of molecular subtypes in the population of IMpassion 130 and 131 trials could be a reason for these results, together with the use of a higher dose of corticosteroids or the different immunomodulation of taxanes. Different combinations of anti PD-L1 agents and chemotherapy are currently being evaluated. Preliminary results from the ENHANCE phase I study showed that the combination of eribulin and pembrolizumab in metastatic TNBC resulted in an ORR in the PD-L1 positive and PD-L1 negative subgroups of 34.5% and 16.1%, respectively. Complete response was achieved in three cases, one of which was in a patient with a PD-L1–negative tumor. The combination was active and effective regardless of PD-L1 status or prior treatment with chemotherapy. Patients who received a combination as a first line had a response rate of 29.2 % vs. 22% in patients who received one or two prior lines [103][28]. Several clinical trials are ongoing in order to improve outcomes in TNBC and in M sub-type (Table 1).

Within these studies, some are evaluating immunotherapy in combination strategy for treatment of TNBC, unfortunately without any distinction in molecular subgroups [104][29].

References

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30.

- Lippman, M.E.; Allegra, J.C. Receptors in Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 1978, 299, 930–933.

- Slamon, D.J.; Leyland-Jones, B.; Shak, S.; Fuchs, H.; Paton, V.; Bajamonde, A.; Fleming, T.; Eiermann, W.; Wolter, J.; Pegram, M.; et al. Use of Chemotherapy plus a Monoclonal Antibody against HER2 for Metastatic Breast Cancer That Overexpresses HER2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 344, 783–792.

- Perou, C.M.; Sørlie, T.; Eisen, M.B.; Van De Rijn, M.; Jeffrey, S.S.; Rees, C.A.; Pollack, J.R.; Ross, D.T.; Johnsen, H.; Akslen, L.A.; et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nat. Cell Biol. 2000, 406, 747–752.

- Prat, A.; Parker, J.S.; Karginova, O.; Fan, C.; Livasy, C.; Herschkowitz, J.I.; He, X.; Perou, C.M. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of the claudin-low intrinsic subtype of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2010, 12, R68.

- Mancini, P.; Angeloni, A.; Risi, E.; Orsi, E.; Mezi, S. Standard of Care and Promising New Agents for Triple Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer. Cancers 2014, 6, 2187–2223.

- Lehmann, B.D.; Bauer, J.A.; Chen, X.; Sanders, M.E.; Chakravarthy, A.B.; Shyr, Y.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification of human tri-ple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Investig. 2011, 121, 2750–2767.

- Lehmann, B.D.; Pietenpol, J.A. Identification and use of biomarkers in treatment strategies for triple-negative breast cancer subtypes. J. Pathol. 2014, 232, 142–150.

- Lehmann, B.D.; Jovanović, B.; Chen, X.; Estrada, M.V.; Johnson, K.N.; Shyr, Y.; Moses, H.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Pietenpol, J.A. Refinement of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes: Implications for Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Selection. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0157368.

- Masuda, H.; Baggerly, K.A.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gonzalez-Angulo, A.M.; Meric-Bernstam, F.; Valero, V.; Lehmann, B.D.; Pietenpol, J.A.; Hortobagyi, G.N.; et al. Differential Response to Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy Among 7 Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Molecular Subtypes. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013, 19, 5533–5540.

- Tutt, A.; Tovey, H.; Cheang, M.C.U.; Kernaghan, S.; Kilburn, L.; Gazinska, P.; Owen, J.; Abraham, J.; Barrett, S.; Barrett-Lee, P.; et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: The TNT Trial. Nat. Med. 2018, 24, 628–637.

- Robson, M.; Im, S.-A.; Senkus, E.; Xu, B.; Domchek, S.M.; Masuda, N.; Delaloge, S.; Li, W.; Tung, N.; Armstrong, A.; et al. Olaparib for Metastatic Breast Cancer in Patients with a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 377, 523–533.

- Litton, J.K.; Rugo, H.S.; Ettl, J.; Hurvitz, S.A.; Gonçalves, A.; Lee, K.-H.; Fehrenbacher, L.; Yerushalmi, R.; Mina, L.A.; Martin, M.; et al. Talazoparib in Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer and a Germline BRCA Mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 753–763.

- Kim, S.B.; Maslyar, D.J.; Dent, R.; Im, S.A.; Espié, M.; Blau, S.; Tan, A.R.; Isakoff, S.J.; Oliveira, M.; Saura, C.; et al. Ipatasertib plus paclitaxel versus placebo plus paclitaxel as first-line therapy for metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (LOTUS): A multi-centre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1360–1372.

- Schmid, P.; Abraham, J.; Chan, S.; Wheatley, D.; Brunt, A.M.; Nemsadze, G.; Baird, R.D.; Park, Y.H.; Hall, P.S.; Perren, T.; et al. Capivasertib Plus Paclitaxel Versus Placebo Plus Paclitaxel as First-Line Therapy for Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: The PAKT Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 423–433.

- Bardia, A.; Mayer, I.A.; Vahdat, L.T.; Tolaney, S.M.; Isakoff, S.J.; Diamond, J.R.; O’Shaughnessy, J.; Moroose, R.L.; Santin, A.D.; Abramson, V.G.; et al. Sacituzumab Govitecan-hziy in Refractory Metastatic Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 741–751.

- Harano, K.; Wang, Y.; Lim, B.; Seitz, R.S.; Morris, S.W.; Bailey, D.B.; Hout, D.R.; Skelton, R.L.; Ring, B.Z.; Masuda, H.; et al. Rates of immune cell infiltration in patients with triple-negative breast cancer by molecular subtype. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0204513.

- Savas, P.P.; Salgado, R.; Denkert, C.; Sotiriou, C.; Darcy, P.K.P.; Smyth, M.J.M.; Loi, S. Clinical relevance of host immunity in breast cancer: From TILs to the clinic. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2016, 13, 228–241.

- Cerbelli, B.; Scagnoli, S.; Mezi, S.; De Luca, A.; Pisegna, S.; Amabile, M.I.; Roberto, M.; Fortunato, L.; Costarelli, L.; Pernazza, A.; et al. Tissue Immune Profile: A Tool to Predict Response to Neoadjuvant Therapy in Triple Negative Breast Cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 2648.

- Mattarollo, S.R.; Loi, S.; Duret, H.; Ma, Y.; Zitvogel, L.; Smyth, M.J. Pivotal role of innate and adaptive immunity in an-thracycline chemotherapy of established tumors. Cancer Res. 2011, 71, 4809–4820.

- Cortes, J.; Cescon, D.W.; Rugo, H.S.; Nowecki, Z.; Im, S.-A.; Yusof, M.M.; Gallardo, C.; Lipatov, O.; Barrios, C.H.; Holgado, E.; et al. KEYNOTE-355: Randomized, double-blind, phase III study of pembrolizumab + chemotherapy versus placebo + chemotherapy for previously untreated locally recurrent inoperable or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1000.

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Diéras, V.; Hegg, R.; Im, S.-A.; Shaw Wright, G.; et al. Atezolizumab and Nab-Paclitaxel in Advanced Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2108–2121.

- Schmid, P.; Adams, S.; Rugo, H.S.; Schneeweiss, A.; Barrios, C.H.; Iwata, H.; Dieras, V.; Henschel, V.; Molinero, L.; Chui, S.Y.; et al. IMpassion130: Updated overall survival (OS) from a global, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, Phase III study of atezolizumab (atezo) + nab-paclitaxel (nP) in previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 37, 1003.

- Schmid, P.; Salgado, R.; Park, Y.; Muñoz-Couselo, E.; Kim, S.; Sohn, J.; Im, S.-A.; Foukakis, T.; Kuemmel, S.; Dent, R.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment of high-risk, early-stage triple-negative breast cancer: Results from the phase 1b open-label, multicohort KEYNOTE-173 study. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 569–581.

- Schmid, P.; Cortes, J.; Bergh, J.C.S.; Pusztai, L.; Denkert, C.; Verma, S.; McArthur, H.L.; Kummel, S.; Ding, Y.; Karantza, V.; et al. KEYNOTE-522: Phase III study of pembrolizumab (pembro) + chemotherapy (chemo) vs placebo + chemo as neoadjuvant therapy followed by pembro vs placebo as adjuvant therapy for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 30, v853–v854.

- Loibl, S.; Untch, M.; Burchardi, N.; Huober, J.; Sinn, B.V.; Blohmer, J.U.; Grischke, E.M.; Furlanetto, J.; Tesch, H.; Hanusch, C.; et al. A randomised phase II study investigating durvalumab in addition to an anthracycline taxane-based neoadjuvant therapy in early triple-negative breast cancer: Clinical results and biomarker analysis of GeparNuevo study. Ann. Oncol. 2019, 30, 1279–1288.

- Primary Results from IMpassion131, a Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Randomised Phase III Trial of First-Line Paclitaxel (PAC) ± Atezolizumab Atez. OncologyPRO. Available online: (accessed on 6 December 2020).

- Tolaney, S.M.; Kalinsky, K.; Kaklamani, V.G.; D’Adamo, D.R.; Aktan, G.; Tsai, M.L.; O’Regan, R.; Kaufman, P.A.; Wilks, S.; Andreopoulou, E.; et al. A phase Ib/II study of eribulin (ERI) plus pembrolizumab (PEMBRO) in metastatic triple-negative breast cancer (mTNBC) (ENHANCE 1). J. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 38, 1015.

- Keenan, T.E.; Tolaney, S.M. Role of Immunotherapy in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 2020, 18, 479–489.