Adverse drug reaction (ADR) is a pressing health problem, and one of the main reasons for treatment failure with antiepileptic drugs. This has become apparent in the event of severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs), which can be life-threatening. Early diagnosis of SCARs that helps in the identification of the culprit drugs is important in the acute stages of the reaction.

- HLA

- cutaneous adverse drug reaction

- SCAR

- genetic polymorphism

- antiepileptics

- CYP450 enzymes

1. Severe Cutaneous Adverse Drug Reactions (SCARs) and AEDs Use

SCARs linked with the use of medications are a type of delayed hypersensitivity reaction that is idiosyncratic, non-predictable and independent of dose. SCARs pose a challenge in the clinical management of patients, as they are related to increased mortality and morbidity, long-term subsequent medical events and high healthcare costs [1].

Skin rash is a common manifestation of ADR in affected individuals. SCARs constitute a large variety of clinical phenotypes, from maculopapular exanthema (MPE) to hypersensitivity syndrome (HSS), SJS, TEN, DRESS and acute generalized acute exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) [2]. A milder form of cutaneous adverse reaction is MPE, a rash that is mild, self-limited and usually resolved after the offending drugs are withdrawn. Unlike MPE, SCARs have serious morbidity, involve systemic manifestation and pose high mortality [3].

About 3% of patients on antiepileptic drugs may develop cutaneous eruptions [4]. A mild form of MPE may occur in about 2.8% of AED users, with phenytoin, lamotrigine and carbamazepine displaying the highest rates (5.9%, 4.8% and 3.7%, respectively), and these reactions may resolve naturally within 3–20 days [5]. Meanwhile, more severe types of cutaneous ADRs including HSS, SJS, TEN and DRESS are less common [6][7]. The histopathology of MPE, DRESS and SJS/TEN is predominated with exocytosis and lymphocyte and macrophage infiltration. In severe cases of SJS/TEN, extensive keratinocyte necrosis is observed. The severity of inflammatory infiltrate and epidermal manifestation increases from MPE to DRESS and SJS/TEN [6].

2. Clinical Manifestations of SCARs

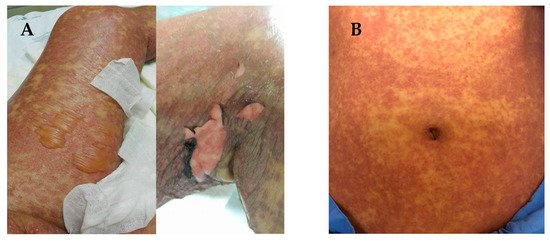

SJS and TEN are characterized by sloughing of the skin, mucosal membranes and the surface of the eye via immune mechanisms that lead to cell death or necrosis [7]. The early stages of SJS/TEN clinical manifestation include fever, malaise, flu-like symptoms, and also symptoms involving eyes, ear, nose and throat for a few days or up to 2 weeks prior to cutaneous manifestations. Cutaneous manifestations of SJS begin with skin pain or a burning sensation (

A,B). It first appears on the face, pre-sternal area of the upper trunk and extremities, and involves erythroderma, purpura, pustules and swelling of the affected area [8]. Symptoms are typically manifested in the proximal parts of the extremities, while the distal parts are relatively spared [9]. In a short period of time, erythematous macules or diffuse erythema will develop over the trunk and extremities. As the red areas develop, the central dusty necrotic areas expand with the subsequent growth of bullae. As the disease progresses, the layers of the full-thickness epidermis will separate, exposing dark red, moist dermis resembling extreme second-degree burns [10][11].

(

) Manifestations of Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS) and toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), in which the skin begins to blister and peel. Erythroderma, extensive skin lesions, aggressive detachment of the epidermis and erosion of mucous membranes can be observed; (

) dermatologic manifestations of drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms (DRESS) typically consist of diffuse pruritic macular and urticarial rash. Facial oedema and periorbital areas with scale and crust around the nose and lip can be found. All patients have provided informed consent before being enrolled and provided the pictures.

A positive Nikolsky sign is significant diagnostic evidence and precedes the occurrence of life-threatening events [12][13]. There is less than 10% and over 30% epidermal detachment in SJS and TEN, respectively. Any disorder with between 10% and 29% epidermal detachment is typically diagnosed as overlapping with SJS/TEN [14]. The clinical presentation of these reactions may also differ among individuals. In one confirmed case of SJS, only mucosal membrane lesions without skin lesions were present in a 14 year-old child [15]. Mucosal membrane involvement may occur in 85% to 95% of SJS and TEN patients; while involvement of conjunctivae, mucous membranes of the nares, mouth, oropharynx, anorectal junction, vulvovaginal area and urethral meatus may occur in 85% to 95% of SJS and TEN patients [16].

Early diagnosis of SCARs that helps in the identification of the culprit drugs is important in the acute stages of the reaction. A prompt recognition helps to improve the management of the disease and limits long-term sequelae. Classification of SCARs is also important in identifying causal drugs. Studies have shown that the interval between drug intake and SCARs onset differ according to the type of SCARs. SJS/TEN has a shorter latency period compared to DRESS [17]. Assessment scores and tools developed to assist in investigation of SCARs to determine clinical patterns and identify causal drugs are discussed in the following section.

References

- Thong, B.Y.-H.; Tan, T.-C. Epidemiology and risk factors for drug allergy. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 71, 684–700.

- Krivoy, N.; Taer, M.; Neuman, M.G. Antiepileptic drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome reactions. Curr. Drug Saf. 2006, 1, 289–299.

- Mehta, M.; Shah, J.; Khakhkhar, T.; Shah, R.; Hemavathi, K.G. Anticonvulsant hypersensitivity syn-drome associated with carbamazepine administration: Case series. J. Pharmacol. Pharmacother. 2014, 5, 59.

- Anwar, T.M.; Faris, P.M. A Systematic Review on Lamotrigine Induced Skin Rashes. J. Drug Deliv. Ther. 2021, 11, 146–151.

- Roujeau, J.-C. The Spectrum of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Clinical Classification. J. Investig. Dermatol. 1994, 102, 28S–30S.

- Duong, T.A.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Wolkenstein, P.; Chosidow, O. Severe cutaneous adverse reactions to drugs. Lancet 2017, 390, 1996–2011.

- Pavlos, R.; Mallal, S.; Phillips, E. HLA and pharmacogenetics of drug hypersensitivity. Pharmacogenomics 2012, 13, 1285–1306.

- Choudhary, S.; McLeod, M.; Torchia, D.; Romanelli, P. Drug Reaction with Eosinophilia and Systemic Symptoms (DRESS) Syndrome. J. Clin. Aesthetic Dermatol. 2013, 6, 31–37.

- Auquier-Dunant, A.; Mockenhaupt, M.; Naldi, L.; Correia, O.; Schröder, W.; Roujeau, J.-C. Correlations Between Clinical Patterns and Causes of Erythema Multiforme Majus, Stevens-Johnson Syndrome, and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Arch. Dermatol. 2002, 138, 1019–1024.

- Irwin, M.F.; Arthur, Z.E.; Klauss, W.K.; Frank, A.; Lowell, A.G.S.K. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 5th ed.; McGraw Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1999.

- Hall, J.B.; Schmidt, G.A.; Wood, L.D.H. Principles of Critical Care, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1999.

- Fritsch, P.O.; Sidoroff, A. Drug-Induced Stevens-Johnson Syndrome/Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2000, 1, 349–360.

- Creamer, D.; Walsh, S.; Dziewulski, P.; Exton, L.; Lee, H.; Dart, J.; Setterfield, J.; Bunker, C.; Ardern-Jones, M.; Watson, K.; et al. UK guidelines for the management of Stevens–Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis in adults 2016. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthetic Surg. 2016, 69, e119–e153.

- French, L.E.; Trent, J.T.; Kerdel, F.A. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in toxic epidermal necrolysis and Stevens–Johnson syndrome: Our current understanding. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2006, 6, 543–549.

- Vanfleteren, I.; Van Gysel, D.; De Brandt, C. Stevens-Johnson Syndrome: A Diagnostic Challenge in the Absence of Skin Lesions. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2003, 20, 52–56.

- Tomy, M.; Hui, L.I. Severe cutaneous adverse drug reactions: A review on epidemiology, etiology, clinical manifestation and pathogenesis. Chin. Med. J. 2008, 121, 756–761.

- Kardaun, S.; Sidoroff, A.; Valeyrie-Allanore, L.; Halevy, S.; Davidovici, B.; Mockenhaupt, M.; Roujeau, J. Variability in the clinical pattern of cutaneous side-effects of drugs with systemic symptoms: Does a DRESS syndrome really exist? Br. J. Dermatol. 2007, 156, 609–611.

Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia