Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Please note this is a comparison between Version 1 by Sophia Kelaini and Version 2 by Catherine Yang.

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are multi-faceted proteins in the regulation of RNA or its RNA splicing, localisation, stability, and translation.

- RNA binding protein

- splicing factor

- translation regulator

1. Introduction

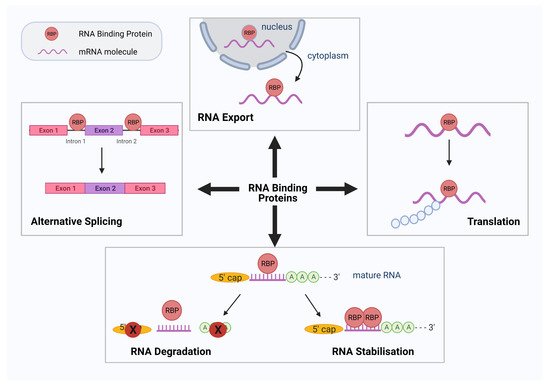

RNA-binding proteins (RBPs) are critical RNA regulators responsible for modulating post-transcriptional events in the cell. RBPs can recognize and interact with binding motifs called RNA recognition motifs (RRM) and/or RNA structure to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for the regulation of various RNA processes such as RNA stability, alternative pre-mRNA splicing, mRNA decay, translocation, post-translational nucleotide modifications, and RNA localization (Figure 1) [1][2][1,2].

Figure 1. Schematic diagram summarizing the various roles of RNA binding proteins (RBPs). RBPs have numerous roles in RNA processing and translation. Four such functions of RBPs are demonstrated diagrammatically above: alternative splicing, RNA export, protein translation, RNA degradation, and stabilization. Figure created using Biorender.com.

2. RBPs in the Pathogenesis of Diabetes and Cardiovascular Disease

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is an increasingly prevalent global health burden [3][6]. DM is a lifelong disease, characterized by chronic hyperglycemia. DM is highly associated with an increased risk of debilitating secondary morbidities manifesting in macrovascular disease (atherosclerosis, ischemic stroke, coronary artery disease) and microvascular disease (diabetic retinopathy, neuropathy, and nephropathy) [4][7]. Close to 10% of worldwide diabetes diagnoses are categorized as Type 1. The remaining majority are diagnosed as Type 2 [5][8], where cells become increasingly resistant to insulin action [6][9], leading to impaired glucose homeostasis with cells unable to internalize circulating blood glucose. Chronic hyperglycemia causes systemic damage to the vasculature triggering multisystemic conditions such as cardiovascular disease (CVD). Additionally, due to the frequency of CVD occurrence in diabetes, it is often considered a CVD in itself. Currently, there is no curative therapy available for diabetes-associated CVD. With rising rates of diabetes, there lies a deepening need for knowledge into the mechanisms behind hyperglycemia-related cardiovascular damage. In vascular endothelial cells (ECs), hyperglycemia has been determined to contribute to a substantial change of gene expression. Transcriptomic analytical assays have uncovered a wide variety of candidate genes implicated in cellular functions such as angiogenesis, coagulation, vascular tone, adhesion, and more. This vascular EC gene expression is tightly controlled by transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms, the latter including regulation of pre-mRNA to mRNA processing, transport, decay and protein translation [7][10]. Precise regulation of these complex post-transcriptional modifications in the RNA network is crucial for the normal function of vascular ECs and the endothelial system. In diabetes, a plethora of RBP-regulated RNA networks are involved in the dysfunction of the vascular endothelium [8][11]. In this section, we will review some of the most common RBPs dysregulated in the pathogenenesis of DM and CVD and their epigenetic effects.

For instance, RNA Binding Fox-1 Homolog 2 (RBFOX2), regulates alternative splicing and is upregulated in the diabetic heart, controlling splicing of genes involved in diabetic cardiomyopathy by binding to target RNA motifs associated with protein trafficking and cell apoptosis [9][10][12,13]. Additionally, Human Antigen R (HuR) also known with its alternative name ELAVL1, is a ubiquitously expressed RBP, which is upregulated and activated under high glucose and in diabetes [11][14]. HuR binds to specific domains known as AU-rich elements (ARE) in the 3′UTRs of target genes that play a role in inflammation and diabetic nephropathy [12][13][14][15,16,17]. Once it is activated, it translocates to the cytoplasm to bind its mRNA targets affecting their stability and translation [15][18]. Tristetraprolin (TTP) binds to 3′ UTR ARE region that results in mRNA destabilization and decay [16][19]. TTP is minimally expressed in healthy aortas but significantly heightened in affected macrophage foam cells as well as ECs of atherosclerotic lesions [17][20]. In another example, Quaking (QKI), an RBP member of the Signal Transduction and Activation of RNA (STAR) protein family and some of its isoforms—namely QKI5, QKI6, QKI7—have been associated with vascular development [16][19]. In our lab, we have previously shown that, compared to controls, there are reduced QKI5 levels in cardiac vessels of diabetic mice, therefore displaying the key status of QKI5 within the diabetic framework of vessel dysfunction. In addition, as we have also reported [18][21], QKI5 played a crucial role in differentiating ECs from induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) via stabilization of VE-cadherin and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 (VEGFR2) activation through Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) signaling. Furthermore, we showed QKI-7 to bind and promote mRNA target degradation such as of VE-cadherin, while the knockdown of QKI7 in a diabetic mouse model of hindlimb ischemia significantly restored reperfusion and blood flow in vivo [19][22].

RBPs are also implicated in the dysfunction of ECs under diabetic conditions in relation to their association with non-protein coding RNAs (ncRNAs), which include long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). The latter are, in fact, responsible for the preponderance of gene transcripts and act as positive or negative regulators based on their interactions with RBPs [20][23]. The importance of the RBP and lncRNAs system as a fundamental part of healthy cellular function through regulation of epigenetic machineries is largely acknowledged [21][24]. In recent years, data from numerous studies has showed a correlation between abnormal levels of lncRNAs and different diseases such as diabetes. For example, the levels of Metastasis-Associated Lung Adenocarcinoma Transcript 1 (MALAT1) were significantly elevated both in vivo (in retinal ECs of a streptozotocin (STZ) diabetic rat model) and in vitro when human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were treated with high glucose. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) knockdown of MALAT1 reduced vascular dysfunction and also decreased reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels in hyperglycemic ECs signifying its connection with diabetic retinopathy and EC dysfunction [22][23][25,26]. Similarly, under diabetic conditions, myocardial infarction associated transcript (MIAT) lncRNA is elevated, as data from studies of diabetic retinas and high-glucose treated ECs have shown. Furthermore, knockdown of MIAT reversed the dysfunction [24][27]. More such examples of lncRNA dysregulation in diabetic conditions exist as in the case of increased antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 Locus (ANRIL) [18][21] promoting pathogenic angiogenesis [25][28] or in the case of Maternally Expressed Gene 3 (MEG3), which had reduced levels in the retinal ECs as shown in an STZ model of diabetic mice [26][29].

34. RBPs and Their Role in Neurodegenerative Disease

Even though the functional mechanisms of RBPs are still not fully elucidated, more recent evidence has indicated that RBPs are key players in the preservation and integrity of neurons. Any defects and alterations in the function of RBPs and in RNA metabolism arising from mutations can cause several neurodegenerative diseases that affect the central nervous system, such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTD), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), fragile X syndrome (FXS), or spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). Other diseases usually associated with aging and that can be affected by RBP dysregulation include Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD). The increasing aging global population has additionally resulted in an increase in the number of worldwide dementia cases, despite a relative decrease in developed countries [27][58]. In the case of ALS for instance, analytical investigations have revealed a strong genetic relationship between mutations of RBP-encoding genes like Ataxin 2 (ATXN2), Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1), Matrin 3 (MATR3) or TIA1 Cytotoxic Granule Associated RNA Binding Protein (TIA-1), and development and progression of the disease [28][29][59,60]. Likewise, in FTD, which shares many common characteristics with ALS [30][31][61,62], fragmentation of RBPs such as TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) in the cytoplasm, has been shown to advance the onset of the disease [32][33][63,64]. In the case of SMA, a serious motor neuron disease, small molecule drug analogs of RG-7916 (SMN-C2 or -C3) were found to selectively regulate alternative splicing of Survival of Motor Neuron 2 (SMN2) by binding to the gene’s pre-mRNA and increasing the affinity of the RBP Far Upstream Element Binding Protein 1 (FUBP1) to it [34][65]. Another neurological syndrome Paraneoplastic opsoclonus-myoclonus ataxia (POMA) is caused by autoantibody secretion against the RBP neuro-oncological ventral antigen 1 and 2 (Nova 1, Nova 2) [35][66], which are neuron-specific found in the nucleus and regulate RNA splicing [36][67]. In another example, myotonic dystrophy (MD) which commonly presents in patients as muscular degeneration, is also characterized by aberrant RNA splicing; CUG triplet repeat (CUGBP) has been specifically linked to MD through its interaction with myotonic dystrophy protein kinase (DMPK) mRNA [37][68].

These types of neurological diseases usually present with aggressive and irreversible characteristics that can prove devastating, and on many occasions even fatal, such as permanent neuron loss, which involves neural cells such as microglia and astrocytes. In neurodegenerative disease a great deal of attention has been concentrated on the different protein aggregates; however, it is of utmost importance to also focus on additional avenues that involve RNA and post transcriptional modifications as a pathogenic component of neurodegenerative disease [38][39][69,70]. In neurons, looking at the high incidence of RNA transport granules may explain why RBP dysfunction can initiate neuronal disease. The RNA granules creation and aggregate formation in a cell’s cytoplasm has been considered to be pathogenic in nature. During cellular stress, RBPs like those with low complexity domains (LCD), such as FUS RNA binding protein (FUS) or hnRNPA1 translocate from the nucleus, where they are usually present, to the cytoplasm and localize in granules [40][41][71,72]. Once there, they transiently form droplet organelles [42][73] with different functions based on their components [43][74]. Higher RBP concentrations can change these functions and lead to the polymerization of LCDs and the creation of amyloid-like fibers and insoluble aggregates [44][75]. Studies on these aggregates are giving rise to hypotheses that in neurons affected by dementias such as ALS or AD, disturbances such as mutations in RBPs play a role in impairing their regular physiological function. In the case of dementias such as AD, a study on RBP-containing stress granules showed their elevated accumulation in the brains of transgenic mice used as a model of tauopathy [45][76]. Furthermore, these granules have an interconnecting role with miRNAs, since the latter interact with RBP to regulate protein translation [46][77], adding an additional layer of complexity.

In general, mutations in the proteins associated with disease increase their propensity for higher aggregation, shifting the balance towards increased creation of more stable, less soluble and, thus, more persistent, stress granules, including secondary granules, which are usually associated with disease. Equally, approaches in neuroprotective therapeutics are directing their efforts against pathogenesis by reducing the creation of stress granules and restoring the balance [47][78].