Inflammation is the main driver of tumor initiation and progression in colitis-associated colorectal cancer (CAC). Recent findings have indicated that the signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6) plays a fundamental role in the early stages of CAC, and STAT6 knockout (STAT6−/−) mice are highly resistant to CAC development. Regulatory T (Treg) cells play a major role in coordinating immunomodulation in cancer; however, the role of STAT6 in the induction and function of Treg cells is poorly understood. To clarify the contribution of STAT6 to CAC, STAT6−/− and wild type (WT) mice were subjected to an AOM/DSS regimen, and the frequency of peripheral and local Treg cells was determined during the progression of CAC. When STAT6 was lacking, a remarkable reduction in tumor growth was observed, which was associated with decreased inflammation and an increased number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells. STAT6 has a direct role in the induction and function of Treg cells during CAC development.

- STAT6

- colorectal cancer

- regulatory T cells

- colitis-associated-cancer

1. Introduction

2. The Absence of STAT6 Increases the Number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Cells in Circulation and Spleen during the Early Stages of CAC Development

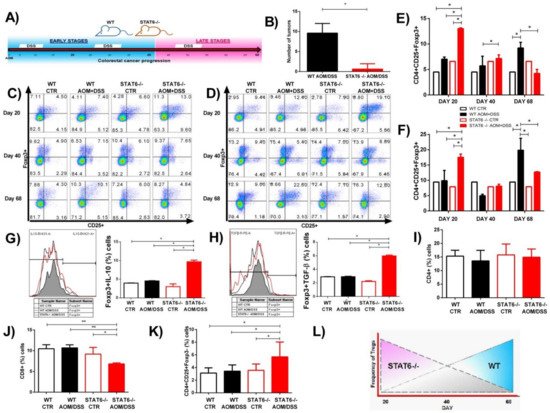

Previously, we determined the role of STAT6 in the development of CAC using the azoxymethane (AOM)/dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) model [13]. STAT6-deficient mice display high resistance to CAC development. The reduced tumorigenicity was associated with diminished inflammation, without changes in the number of goblet cells, and a decreased mRNA expression of IL-17A and TNFα but increased IL-10 expression in early CAC (Day-20), compared to WT mice [13]. Considering that inflammation is the main driver of tumor initiation in CAC, one potential mechanism contributing to the suppression of the inflammatory response in STAT6−/− mice may be the increased recruitment of Treg cells. Patients with more Foxp3+ cells in CAC tended to have a better prognosis [18]. To test this hypothesis, we subjected WT and STAT6−/− mice to an AOM/DSS regimen and analyzed the CAC progression at Day 20, Day 40 (early stages), and Day 68 (late stage of tumor development, where adenoma-like lesions are observed) as an approximation of different stages of tumor progression (Figure 1A). As expected, the WT mice displayed both increased numbers of tumors as well as increased tumor load at Day 68 (9.6 ± 2.4), whereas only 30% of STAT6–/– animals developed tumors, and they were scarce (0.6 ± 1.3, p < 0.05) (Figure 1B). Next, we analyzed the kinetics of Treg cells (CD4+CD25+Foxp3+) at Day 20, Day 40, and Day 68 after AOM injection by flow cytometry in blood and spleens (Figure 1C,D). In the WT AOM/DSS animals, Treg cells were maintained at a similar frequency as those in control animals in the blood and spleen at Day 20 and Day 40. However, remarkably, a significant increase in the frequency of Treg cells was observed at Day 68, compared to the control and STAT6−/− AOM/DSS mice (9.44 ± 0.1 vs. 19.85 ± 3.8, p < 0.05; 12.7 ± 0.1 vs. 19.85 ± 3.8, p < 0.05) (Figure 1C–F). In contrast, we found an increased Treg frequency in the blood and spleen of STAT6−/− AOM/DSS animals at Day 20 (early stages of tumor development), compared to the control and WT AOM/DSS mice (17.5 ± 1 vs. 9.44 ± 0.1, p < 0.05; 17.5 ± 1 vs. 9.8 ± 3.3, p < 0.05) (Figure 1C–F). There was no difference in the frequency of Treg cells between the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS, WT AOM/DSS, and control mice at Day 40. However, on Day 68, the Treg cell frequency dropped in STAT6−/− AOM/DSS animals to similar levels as those in control mice, which is consistent with the fact that there was a lower tumor load (Figure 1C–F). Given that the secretion of suppressive cytokines, such as TGF-β and IL-10, has been considered a mechanism used by Treg cells to suppress the immune responses [14], we decided to evaluate whether Treg cells isolated from spleens with early-stage CAC development (Day 20) may show a different expression of these cytokines under STAT6 deficiency. As shown in Figure 1G,H, at Day 20 of the CAC progression, we observed a higher expression of TGF-β and IL-10 cytokines in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ cells (Figure 1H) from STAT6−/− AOM/DSS compared to WT AOM/DSS mice. In addition, the frequency of CD4+ cells at Day 20 in the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS and WT AOM/DSS animals was similar (Figure 1I). However, at this time, the proportion of CD8+ cells was lower in the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS in comparison to the WT AOM/DSS mice (Figure 1J). On Day 20, the number of CD4+CD25+Foxp3- cells was higher in STAT6−/− AOM/DSS mice compared to WT AOM/DSS animals (Figure 1K).

3. STAT6 Deficiency Increase the Accumulation of Treg Cells in the Colon in Early CAC

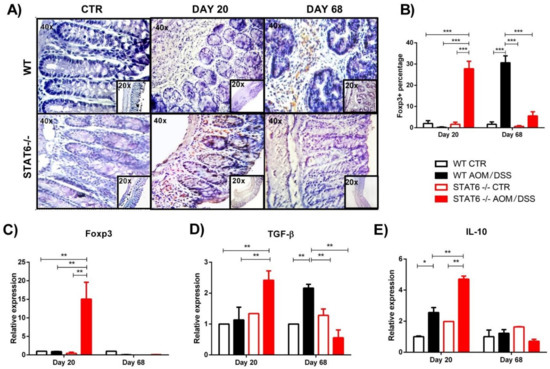

The defective colonic inflammatory response observed in the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS mice at the early stages of CAC, which is correlated with few tumor developments, led us to examine the local recruitment of Treg cells. We analyzed the colonic protein expression of Foxp3 by immunohistochemistry during the early and late stages of colon tumorigenesis. Our analysis revealed a significantly increased accumulation of Foxp3+ cells in the colon of the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS mice, compared to the WT AOM/DSS animals, at Day 20 of the CAC progression (27.8 ± 7.8 vs. 0.2 ± 0.05, p < 0.001) (Figure 2A,B). In contrast, during the advanced stages of tumor development (Day 68), the Foxp3+ cells were significantly higher in the tumor-bearing WT mice, compared to the STAT6−/− AOM/DSS animals, (30.6 ± 7.3 vs. 5.6 ± 4.2, p < 0.001) (Figure 2A,B). Colonic biopsies of the control mice showed barely detectable Foxp3 staining (Figure 2A,B).

4. Discussion

STAT6 has important roles in the function and activation of immune cells. Here, we showed that STAT6 deficiency is necessary for controlling tumor growth in a model of CAC. Mechanistically, the absence of STAT6 resulted in an increased accumulation of local and peripheral Treg cells and overexpression of molecules associated with the function of Treg cells during the initial stages of CAC. These data are in accordance with our previous analyses, where the colons of STAT6−/− mice showed a reduction in cell infiltration and decreased production of proinflammatory markers and cytokines in the initial tumor stage [13]. Early depletion of Treg cells during CAC development in STAT6−/− mice restores tumor growth, along with inflammatory infiltration in the colon. These data identify STAT6 as a critical pathway for the induction and function of Treg cells during CAC progression. IL-4 and IL-13 are canonical inducers of STAT6 activation when dimers of STAT6 become phosphorylated and are translocated to the nucleus, where they activate or repress target genes. Phospho-STAT6 (p-STAT6) levels have been commonly detected in the colon of patients with clinically detectable CD or UC, and tumoral p-STAT6 is positively correlated to a clinical-stage and poor prognosis of human CRC [9][12]. The STAT6 signaling pathway favors the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins [11] and promotes the proliferation of polyp epithelial cells in the colon [12]. Similarly, the persistent activation of STAT6 modifies the expression of proteins involved in epithelial barrier permeability and interrupts tight junction integrity, resulting in the recurrent exposure of luminal microbiota, favoring inflammation and CAC development [12][27]. While these findings suggest the intrinsic importance of STAT6 in regulating tumor growth, our studies have found an important role of STAT6 in non-tumor cells for controlling tumor growth. AOM/DSS administration resulted in a significant decrease in inflammation and tumor development under STAT6 deficiency. In addition, in the STAT6−/− animals, we found a remarkable increase in the frequency of Treg cells during early CAC, relative to the WT mice. The relationship between STAT6 and immune cells was shown to be important in a model of oxazolone-induced colitis, where T cells, macrophages, and natural killer T cells exhibit increased STAT6 phosphorylation during colitis development [27]. Additionally, ApcMin/+Stat6−/− mice developed few polyps, with a reduced proliferation at the small intestine and MDSCs expansion, decreased PD-1 expression in CD4+ cells, and strong CD8-mediated cytotoxic response [28]. Treg cells have an oncogenic role in tumor progression through the suppression of antitumor immunity and prevention of an active cytotoxic process [29]. Chemokines and cytokines are released in the tumor microenvironment (TME) by cancer cells and tumor stroma-infiltrating cells, leading to the recruitment of Treg cells. In the TME of many tumors, Treg cells suppress effector immune responses, overwhelming the anti-tumor activity mediated by natural killer cells and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells. However, the role of Treg cells in CRC is controversial. Some reports relate Foxp3+ cell infiltration with poor clinical outcomes [30][31][32]. The colonic increase in Foxp3(+) cells is significantly higher in patients with CRC, compared to healthy controls or patients with inflammatory bowel disease [33], and Treg cells with a higher expression of several molecules that correlate with suppression, such as Tim-3, LAG-3, TGF-β, IL-10, CD25, and CTLA-4, are observed in CRC patients [31]. In contrast, a local accumulation and Foxp3 (+) cell density is associated with an improved survival rate and is considered as a good independent prognostic biomarker in the initial stage of colorectal cancers [19][34][35]. The role of Treg cells in CRC seems to be dependent on the co-existence in the tumor tissue and the time of action of different subsets of Foxp3-expressing cells. A study identified two types of Treg cells in CRC, Foxp3hi Treg cells and Foxp3lo non-suppressive T cells [20]. The latter are characterized by secreted inflammatory cytokines along with the instability of Foxp3 and the absence of CD45RA expression, a naive T cell marker [20]. In the present study, we found that in early CAC development, Treg cells were efficiently recruited in STAT6−/− colons, whereas increasing Foxp3 (+) cells in the colon of WT mice were detected only in the late stages of CAC. Interestingly, our previous results for WT mice showed that Treg cells from the late stages of CAC displayed an activated phenotype by expressing PD1, CD127, and Tim-3, along with an increased suppressive capacity in T-CD4+ and T-CD8+ cells. In contrast, Treg cells from WT mice in early CAC were scant and less suppressive [21]. Due to the lack of STAT6−/− Foxp3EGFP reporter mice, we were not able to determine the suppressive capacity of Treg cells in vitro that developed under STAT6 deficiency. However, the immunohistological analyses and H&E staining showed that the STAT6−/− CAC-induced mice displayed decreased inflammatory infiltrate, with less destruction of the intestinal muscle and mucosa, supporting the idea that immunoregulatory mechanisms are taking place. Furthermore, the significant decrease in CD8+ T cells and the positive correlation between the frequency of Treg cells and the transcription levels of Foxp3, TGF-beta, and IL-10 in STAT6−/− colons indicate that the latter is a consequence of the modulating function of Treg cells during CAC progression. Some authors have suggested that distinct subpopulations of tumor-infiltrating Foxp3 (+) T cells contribute in opposing ways to the determination of CRC prognosis [36][37]. During the early CAC development, epithelial tight junction dysfunction promotes enhanced gut permeability, resulting in the deregulation of the interactions between the intestinal epithelial cells, immune cells, and gut microbiota. Continual exposure to luminal microbiota leads to intestinal inflammation, characterized by the recruitment of innate immune cells, the release of inflammatory mediators, and the subsequent generation and expansion of T-helper 17 (Th17) cells [38]. The local increase of Treg cells in early CAC could suppress or prevent tumor formation through Th17 cell suppression. Here, we use an anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody (PC61) to deplete Treg cells only during early CAC. Interestingly, we observed histological damage and tumor growth recovery during STAT6 deficiency, supporting the idea that Treg cells developed in STAT6−/− mice are protective against colon tumorigenesis. This finding seems to be compatible with that of a recent study showing that the administration of the natural compound, Parthenolide, during experimental colitis significantly relieved colon inflammation and improved the colitis symptoms [39]. The protective effect of this molecule was associated with an increased frequency of colonic Treg cells, a downregulation of the ratio of colonic Th17 cells, together with a more abundant gut microbial diversity and flora composition [39]. One possible reason for the protection observed in the STAT6−/− mice during CAC progression could be the alterations in gut microbiota. Thus, this condition needs further research. Because the balance between Th17/Treg cells and these regulatory factors is decisive in CAC progression, it could be interesting to determine if the tumor growth observed in STAT6−/− mice after Treg depletion is Th17-mediated. Depending on the grade of alteration during CRC progression, Treg cells may modify their phenotype and exert different effects on cancer progression. Foxp3 (+) cells infiltrating colorectal carcinomas could be associated with their capacity to suppress tumor-promoting inflammatory immune response caused by infectious stimuli from bacterial translocation through the mucosal barrier [40]. In a number of murine models, adoptively transferred Treg cells prevent the onset of colitis or treat established colitis [41][42][43], and the in vitro expansion of Treg cells from the blood of patients with CD is considered as a feasible adoptive cell therapy for this disease [44][45]. The significantly higher percentages of Treg cells found in STAT6−/− CAC-induced colons, compared with those found in WT colons, suggest that STAT6 limits Treg generation and recruitment by undetermined mechanisms. Additionally, a previous study from our laboratory demonstrated that the number of circulating CD11b+Ly6ChiCCR2+ monocytes and CD11b+Ly6ClowLy6G+ granulocytes was decreased in a STAT6-dependent manner [13]. Additionally, a significant reduction in the expression of the chemokines, CCL9, and CCL25, and the chemokine receptor, CXCR2, both involved in the recruitment of inflammatory cells, was shown in STAT6−/− mice during CAC progression. CCR2 is responsible for the recruitment of Ly6Chi “inflammatory monocytes” to peripheral sites of inflammation, where they display inflammatory, phagocytic, and proteolytic functions [46]. Thus, the STAT6 pathway in Treg cells has an intricate outcome and should be addressed in the context of an inflammatory environment. However, the local increase of Foxp3 (+) cells could be used to suppress antitumor immunity in the final phase of tumor formation. In our lab, when the Treg cells were depleted during the second DSS cycle of experimental CAC in WT mice, a reduction of 50% of Treg cells resulted in a better prognostic value, with a significant reduction in the tumor load [22]. In contrast, in the present study, an earlier Treg depletion slightly increased the tumor load in WT mice. All these results suggest that Treg cells have a dynamic behavior influenced by STAT6 during CAC development. Recently, a study demonstrated that STAT6 plays a critical role in the generation of Treg cells induced by B cells (Treg-of-B cells) [47]. STAT6 phosphorylation was associated with the capacity of Treg-of-B cells to alleviate inflammation in an animal model of asthma in vivo [47]. In accordance with our results, in an allergic disease model, a high number of Treg cells in the lungs and spleens in STAT6−/− mice, compared to WT animals, were associated with a decreased allergic response [26]. However, it would be interesting to determine if the stability in the expression of Foxp3 and therefore the differentiation and functional properties of Treg cells are modified in a STAT6-dependent manner. Furthermore, the role of STAT6 in modulating different types of Treg cells (natural, induced, type 1 T regulatory cells, and Treg-of-B cells) may be useful to develop new therapeutic strategies for relieving CAC or CRC. In conclusion, STAT6 seems to play a central role in the regulation of the activity of Treg cells, particularly during the initial stages of CAC development, through the modulation of intense inflammatory responses.References

- Siegel, R.; DeSantis, C.; Jemal, A. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2014, 64, 104–117.

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2021, 68, 394–424.

- Colotta, F.; Allavena, P.; Sica, A.; Garlanda, C.; Mantovani, A. Cancer-related inflammation, the seventh hallmark of cancer: Links to genetic instability. Carcinogenesis 2009, 30, 1073–1081.

- Van Der Kraak, L.; Gros, P.; Beauchemin, N. Colitis-associated colon cancer: Is it in your genes? World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 11688–11699.

- Hebenstreit, D.; Wirnsberger, G.; Horejs-Hoeck, J.; Duschl, A. Signaling mechanisms, interaction partners, and target genes of STAT6. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2006, 17, 173–188.

- Delgado-Ramirez, Y.; Colly, V.; Gonzalez, G.V.; Leon-Cabrera, S. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 as a target in colon cancer therapy (Review). Oncol. Lett. 2020, 20, 455–464.

- Andre, F.; Arnedos, M.; Baras, A.S.; Baselga, J.; Bedard, P.L.; Berger, M.F.; Bierkens, M.; Calvo, F.; Cerami, E.; Chakravarty, D.; et al. AACR Project GENIE: Powering Precision Medicine through an International Consortium. Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 818–831.

- Uhlén, M.; Zhang, C.; Lee, S.; Sjöstedt, E.; Fagerberg, L.; Bidkhori, G.; Benfeitas, R.; Arif, M.; Liu, Z.; Edfors, F.; et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science 2017, 357, eaan2507.

- Wang, C.-G.; Ye, Y.-J.; Yuan, J.; Liu, F.-F.; Zhang, H.; Wang, S. EZH2 and STAT6 expression profiles are correlated with colorectal cancer stage and prognosis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2421–2427.

- Wick, E.C.; Leblanc, R.E.; Ortega, G.; Robinson, C.; Platz, E.; Pardoll, E.M.; Iacobuzio-Donahue, C.; Sears, C.L. Shift from pStat6 to pStat3 predominance is associated with inflammatory bowel disease-associated dysplasia. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2012, 18, 1267–1274.

- Li, B.H.; Yang, X.Z.; Li, P.D.; Yuan, Q.; Liu, X.H.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, W.J. IL-4/Stat6 activities correlate with apoptosis and metastasis in colon cancer cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008, 369, 554–560.

- Lin, Y.; Li, B.; Yang, X.; Liu, T.; Shi, T.; Deng, B.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, L.; Jiang, Z.; He, R. Non-hematopoietic STAT6 induces epithelial tight junction dysfunction and promotes intestinal inflammation and tumorigenesis. Mucosal Immunol. 2019, 12, 1304–1315.

- Leon-Cabrera, S.A.; Molina-Guzman, E.; Delgado-Ramirez, Y.G.; Vázquez-Sandoval, A.; Ledesma-Soto, Y.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.G.; Chirino, Y.I.; Delgado-Buenrostro, N.L.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; et al. Lack of STAT6 Attenuates Inflammation and Drives Protection against Early Steps of Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2017, 5, 385–396.

- Olguín, J.E.; Medina-Andrade, I.; Rodríguez, T.; Rodríguez-Sosa, M.; Terrazas, L.I. Relevance of Regulatory T Cells during Colorectal Cancer Development. Cancers 2020, 12, 1888.

- Liu, Z.; Huang, Q.; Liu, G.; Dang, L.; Chu, D.; Tao, K.; Wang, W. Presence of FOXP3+Treg cells is correlated with colorectal cancer progression. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Med. 2014, 7, 1781–1785.

- Argon, A.; Vardar, E.; Kebat, T.; Ömer, E.; Erkan, N. The Prognostic Significance of FoxP3+ T Cells and CD8+ T Cells in Colorectal Carcinomas. J. Environ. Pathol. Toxicol. Oncol. 2016, 35, 121–131.

- Reimers, M.S.; Engels, C.C.; Putter, H.; Morreau, H.; Liefers, G.J.; Van De Velde, C.J.H.; Kuppen, P.J.K. Prognostic value of HLA class I, HLA-E, HLA-G and Tregs in rectal cancer: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 2014, 14, 486.

- Soh, J.S.; Jo, S.I.; Lee, H.; Do, E.-J.; Hwang, S.W.; Park, S.H.; Ye, B.D.; Byeon, J.-S.; Yang, S.-K.; Kim, J.H.; et al. Immunoprofiling of Colitis-associated and Sporadic Colorectal Cancer and its Clinical Significance. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1–10.

- Vlad, C.; Kubelac, P.; Fetica, B.; Vlad, D.; Irimie, A.; Achimas-Cadariu, P. The prognostic value of FOXP3+ T regulatory cells in colorectal cancer. J. BUON 2015, 20, 114–119.

- Saito, T.; Nishikawa, H.; Wada, H.; Nagano, Y.; Sugiyama, D.; Atarashi, K.; Maeda, Y.; Hamaguchi, M.; Ohkura, N.; Sato, E.; et al. Two FOXP3+CD4+ T cell subpopulations distinctly control the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Nat. Med. 2016, 22, 679–684.

- Olguín, J.E.; Medina-Andrade, I.; Molina, E.; Vázquez, A.; Pacheco-Fernández, T.; Saavedra, R.; Pérez-Plasencia, C.; Chirino, Y.I.; Vaca-Paniagua, F.; Arias-Romero, L.E.; et al. Early and Partial Reduction in CD4+Foxp3+ Regulatory T Cells during Colitis-Associated Colon Cancer Induces CD4+ and CD8+ T Cell Activation Inhibiting Tumorigenesis. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 239–249.

- Bruns, H.A.; Schindler, U.; Kaplan, M.H. Expression of a Constitutively Active Stat6 In Vivo Alters Lymphocyte Homeostasis with Distinct Effects in T and B Cells. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 3478–3487.

- Sanchez-Guajardo, V.; Tanchot, C.; O’Malley, J.T.; Kaplan, M.H.; Garcia, S.; Freitas, A.A. Agonist-driven development of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells requires a second signal mediated by Stat6. J. Immunol. 2007, 178, 7550–7556.

- Zorn, E.; Nelson, E.A.; Mohseni, M.; Porcheray, F.; Kim, H.; Litsa, D.; Bellucci, R.; Raderschall, E.; Canning, C.; Soiffer, R.J.; et al. IL-2 regulates FOXP3 expression in human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells through a STAT-dependent mechanism and induces the expansion of these cells in vivo. Blood 2006, 108, 1571–1579.

- Takaki, H.; Ichiyama, K.; Koga, K.; Chinen, T.; Takaesu, G.; Sugiyama, Y.; Kato, S.; Yoshimura, A.; Kobayashi, T. STAT6 inhibits TGF-beta 1-mediated Foxp3 induction through direct binding to the Foxp3 promoter, which is reverted by retinoic acid receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 14955–14962.

- Dorsey, N.J.; Chapoval, S.P.; Smith, E.P.; Skupsky, J.; Scott, D.W.; Keegan, A.D. STAT6 controls the number of regulatory T cells in vivo, thereby regulating allergic lung inflammation. J. Immunol. 2013, 191, 1517–1528.

- Rosen, M.J.; Chaturvedi, R.; Washington, M.K.; Kuhnhein, L.A.; Moore, P.D.; Coggeshall, S.S.; McDonough, E.M.; Weitkamp, J.-H.; Singh, A.B.; Coburn, L.A.; et al. STAT6 deficiency ameliorates severity of oxazolone colitis by decreasing expression of claudin-2 and Th2-inducing cytokines. J. Immunol. 2013, 190, 1849–1858.

- Jayakumar, A.; Bothwell, A.L. Stat6 Promotes Intestinal Tumorigenesis in a Mouse Model of Adenomatous Polyposis by Expansion of MDSCs and Inhibition of Cytotoxic CD8 Response. Neoplasia 2017, 19, 595–605.

- Vignali, D.A.A.; Collison, L.W.; Workman, C.J. How regulatory T cells work. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008, 8, 523–532.

- Ling, Z.-A.; Zhang, L.-J.; Ye, Z.-H.; Dang, Y.-W.; Chen, G.; Li, R.-L.; Zeng, J.-J. Immunohistochemical distribution of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in colorectal cancer patients. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Patho. 2018, 11, 1841–1854.

- Ma, Q.; Liu, J.; Wu, G.; Teng, M.; Wang, S.; Cui, M.; Li, Y. Co-expression of LAG3 and TIM3 identifies a potent Treg population that suppresses macrophage functions in colorectal cancer patients. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2018, 45, 1002–1009.

- Norton, S.E.; Ward-Hartstonge, K.A.; McCall, J.L.; Leman, J.K.H.; Taylor, E.S.; Munro, F.; Black, M.A.; Groth, B.F.D.S.; McGuire, H.M.; Kemp, R.A. High-Dimensional Mass Cytometric Analysis Reveals an Increase in Effector Regulatory T Cells as a Distinguishing Feature of Colorectal Tumors. J. Immunol. 2019, 202, 1871–1884.

- Clarke, S.L.; Betts, G.J.; Plant, A.; Wright, K.L.; El-Shanawany, T.M.; Harrop, R.; Torkington, J.; Rees, B.I.; Williams, G.T.; Gallimore, A.M.; et al. CD4+CD25+FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells Suppress Anti-Tumor Immune Responses in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2006, 1, e129.

- Hanke, T.; Melling, N.; Simon, R.; Sauter, G.; Bokemeyer, C.; Lebok, P.; Terracciano, L.M.; Izbicki, J.R.; Marx, A.H. High intratumoral FOXP3+ T regulatory cell (Tregs) density is an independent good prognosticator in nodal negative colorectal cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 8227–8235.

- Shang, B.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, S.J.; Liu, Y. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating FoxP3(+) regulatory T cells in cancers: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 1–9.

- Saito, T.; Yamashita, K.; Tanaka, K.; Yamamoto, K.; Makino, T.; Takahashi, T.; Kurokawa, Y.; Yamasaki, M.; Wada, H.; Nishikawa, H.; et al. Impact of tumor infiltrating effector regulatory T cells on the prognosis of colorectal cancers. Cancer Sci. 2021, 112, 390.

- Fantini, M.C.; Favale, A.; Onali, S.; Facciotti, F. Tumor Infiltrating Regulatory T Cells in Sporadic and Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer: The Red Little Riding Hood and the Wolf. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 6744.

- Omenetti, S.; Pizarro, T.T. The Treg/Th17 Axis: A Dynamic Balance Regulated by the Gut Microbiome. Front. Immunol. 2015, 6, 639.

- Liu, Y.-J.; Tang, B.; Wang, F.-C.; Tang, L.; Lei, Y.-Y.; Luo, Y.; Huang, S.-J.; Yang, M.; Wu, L.-Y.; Wang, W.; et al. Parthenolide ameliorates colon inflammation through regulating Treg/Th17 balance in a gut microbiota-dependent manner. Theranostics 2020, 10, 5225–5241.

- Ladoire, S.; Martin, F.; Ghiringhelli, F. Prognostic role of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells infiltrating human carcinomas: The paradox of colorectal cancer. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2011, 60, 909–918.

- Maloy, K.J.; Salaun, L.; Cahill, R.; Dougan, G.; Saunders, N.J.; Powrie, F. CD4(+)CD25(+) T-R cells suppress innate immune pathology through cytokine-dependent mechanisms. J. Exp. Med. 2003, 197, 111–119.

- Mottet, C.; Uhlig, H.H.; Powrie, F. Cutting Edge: Cure of Colitis by CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T Cells. J. Immunol. 2003, 170, 3939–3943.

- Watanabe, K.; Rao, V.P.; Poutahidis, T.; Rickman, B.H.; Ohtani, M.; Xu, S.; Rogers, A.B.; Ge, Z.; Horwitz, B.H.; Fujioka, T.; et al. Cytotoxic-T-Lymphocyte-Associated Antigen 4 Blockade Abrogates Protection by Regulatory T Cells in a Mouse Model of Microbially Induced Innate Immune-Driven Colitis. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 5834–5842.

- Canavan, J.B.; Scotta, C.; Vossenkamper, A.; Goldberg, R.; Elder, M.J.; Shoval, I.; Marks, E.; Stolarczyk, E.; Lo, J.W.; Powell, N.; et al. Developing in vitro expanded CD45RA(+) regulatory T cells as an adoptive cell therapy for Crohn’s disease. Gut 2016, 65, 584–594.

- Clough, J.N.; Omer, O.S.; Tasker, S.; Lord, G.M.; Irving, P.M. Regulatory T-cell therapy in Crohn’s disease: Challenges and advances. Gut 2020, 69, 942–952.

- Desalegn, G.; Pabst, O. Inflammation triggers immediate rather than progressive changes in monocyte differentiation in the small intestine. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1–14.

- Chu, K.-H.; Lin, S.-Y.; Chiang, B.-L. STAT6 Pathway Is Critical for the Induction and Function of Regulatory T Cells Induced by Mucosal B Cells. Front. Immunol. 2021, 11, 11.