Astroviruses (AstVs) are non-enveloped, positive single-stranded RNA viruses that cause a wide range of inflammatory diseases in mammalian and avian hosts.

- astrovirus

- capsid

- structure

- crystallography

- virus maturation

1. Introduction

Astroviruses (AstVs) are positive, single-stranded RNA (+ssRNA), non-enveloped viruses. The family

Astroviridae

consists of two genera,

Mamastrovirus

and

Avastrovirus, that infect a broad range of mammalian and avian hosts, respectively [1,2]. Classical human astroviruses (HAstVs) are classified into eight serotypes (i.e., HAstV-1 to 8), which are known to cause mild to severe gastroenteritis, usually in small children [2,3]. However, there have been recent cases of emerging HAstVs from two new clades, VA and MLB, that are associated with more severe gastroenteritis and neural pathogenesis [4,5,6]. This is especially interesting because animal AstVs are known to cause various inflammatory diseases in their hosts, ranging from gout in chickens, encephalitis in cows, and a degenerative neural infection in minks [7,8,9]. Furthermore, advances in environmental sampling and DNA sequencing technology indicate an increasingly expansive range of hosts. An earlier review by Arias and DuBois has gone into detail about the AstV capsid structure and its roles in virus infection and pathogenesis [10]. The goal of this review is to highlight the most recent findings about the structure and function of the AstV structural proteins and discuss future directions that are urgently needed to address outstanding research questions.

, that infect a broad range of mammalian and avian hosts, respectively [1][2]. Classical human astroviruses (HAstVs) are classified into eight serotypes (i.e., HAstV-1 to 8), which are known to cause mild to severe gastroenteritis, usually in small children [2][3]. However, there have been recent cases of emerging HAstVs from two new clades, VA and MLB, that are associated with more severe gastroenteritis and neural pathogenesis [4][5][6]. This is especially interesting because animal AstVs are known to cause various inflammatory diseases in their hosts, ranging from gout in chickens, encephalitis in cows, and a degenerative neural infection in minks [7][8][9]. Furthermore, advances in environmental sampling and DNA sequencing technology indicate an increasingly expansive range of hosts. An earlier review by Arias and DuBois has gone into detail about the AstV capsid structure and its roles in virus infection and pathogenesis [10]. The goal of this review is to highlight the most recent findings about the structure and function of the AstV structural proteins and discuss future directions that are urgently needed to address outstanding research questions.

2. Astrovirus Capsid Maturation Is a Host-Driven Process

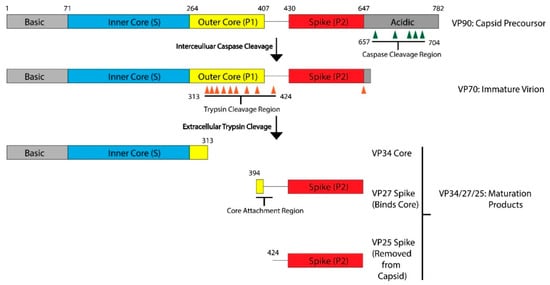

The AstV capsid is first assembled from a polyprotein expressed from the open reading frame 2 (ORF2) located at the 3′-end of the viral RNA genome. ORF2 is translated from a subgenomic RNA, and the lack of sequence similarity in ORF2 to other enteric viruses including picornaviruses and caliciviruses led to the classification of AstVs into a separate family [10]. AstV ORF2 is translated into a five-domain protein called VP90, which is approximately 90kD in size. From N-terminus to C-terminus, the VP90 polypeptide folds into the basic domain (~80 aa), the inner core (S, ~180 aa), the outer core (P1, ~150 aa), the spike (P2, ~200 aa) and the acidic domain (~140 aa) (

). After translation, 180 subunits are assembled into the T = 3 icosahedral capsid and form the VP90 state of the virus. In cellular studies, VP90 mostly associates with the membrane fractions [11]. VP90 can dissociate from the membranes and become soluble after cleavage by proteases, specifically caspases from virus-induced apoptosis [11][12][13]. There are several candidate caspase cleavage sites in the C-terminal acidic domain, and this maturation occurs over a period of 10–20 min after translation [14]. The involvement of host caspases in viral protein cleavage and processing is a process that is not unique to AstVs, having been reported in other viruses including parvovirus, human papillomavirus and SARS-coronavirus [15]. Unlike these other viruses, other than the removal of the ~20 kD acidic domain and dissociation from membranes, very little is known about the role or importance of these caspase cleavages in the transition of the VP90 state to the VP70 state. It is possible that VP90 may play a role in viral capsid assembly or help suppressing host immune response by sequestering the viral capsid and RNA to host membranes, but further studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

Maturation Process Modeled with HAstV-8. After translation, the viral capsid protein forms the VP90 precursor. The acidic domain is cleaved by caspases along sites in the acidic domain, resulting in the VP70 immature virion. This VP70 virion exits the cell, where it is exposed to extracellular proteases. There are multiple trypsin cleavage sites in the P1 outer core domain, leading to the generation of the VP34 core, VP27 spike, and VP25 spike domains. These three products, and possibly some of the digested peptides from the outer core domain, assemble into the VP34/27/25 mature capsid. VP27 can form a homodimer and associate with the VP34 core domain. VP25, which has the core attachment region cleaved, is not present in the mature particle. Domains and regions are numbered according to the sequence of HAstV-8, but the domain architecture and many of the protease cleavage sites are conserved across HAstV-1 to 8 serotypes. Adapted from [16][17].

After the removal of the acidic domain by caspases, the astrovirus capsid is converted into the VP70 state. The virus can now dissociate from cellular membranes and exit the cell [18]. AstV infection increases cell-to-cell and tight junction permeability without inducing cell death, indicating that the VP70 exits from intestinal cells in a non-lytic fashion [19]. However, the capsid properties and host membrane remodeling process that allow for non-lytic exit are unknown. Very few functional studies have been conducted on the VP70 state of the virus, but it appears to be a transitory state that is stable in the extracellular environment. Astrovirus with the VP70 capsid is non-infectious, however, and infectivity requires a maturation step that involves another round of proteolytic processing by host extracellular proteases. In vitro, the VP70 capsid can be matured by trypsin to the VP34/27/25 state [20][21]. On SDS-PAGE, mature astrovirus capsid produces three bands at 34 kD, 27 kD and 25 kD that roughly correspond to the inner core domain, the longer and the shorter version of the spike domain, respectively. The VP34 core is separated from the VP27/25 spike domains [20], with a gap of approximately 80 amino acids in between that is unaccounted for in the SDS-PAGE [16]. Therefore, the VP27 spikes are retained in the mature astrovirus particle due to noncovalent inter-domain binding rather than covalent polypeptide linkage, with the VP25 dissociating from the mature viral capsid during the trypsin cleavage. Functionally, trypsin treatment increases the infectivity of the viral particles by up to 10

fold. The molecular determinant of the trypsin-imparted infectivity is unknown, but proposed to be related to the loss of 60 capsid spikes and freeing of a possible functional motif(s) on the capsid [20][21].

In summary, the AstV capsid maturation process is quite dynamic, resulting in the virus moving from a non-infectious intracellular state (VP90) to a primed extracellular state (VP70), and finally to a fully mature and infectious particle (VP34/27/25). This process is driven by the host proteases, which may have a major role in virus–host interactions and tissue/cellular tropism. There are still many unanswered questions related to viral maturation process, such as the level of conservation across strains, capsid functions enabled by maturation, and the nature of protease factors driving maturation in different hosts or different tissue environments.

3. Capsid Structures and Modelling Provide Insights into Serotype Variability

X-ray crystallography studies have produced several high-resolution structures that reveal an extensive amount of information about individual domains of the AstV capsid and the level of variations across strains (

and

). These structures cover two main regions of the virus, the S/P1 core domains and the P2 spike domain. Currently, there are no high-resolution structures of the N-terminal basic or C-terminal acidic domains. The N-terminal basic domain is rich in lysine and arginine residues but is predicted to have very little secondary structure. The C-terminal acidic domain is predicted to have a number of short alpha helixes, but the rest of the domain is unstructured and has regions high in aspartate and glutamate [22]. It has been difficult to obtain crystal structures of the N- and C-terminal domains due to their high charge content and the lack of secondary structures.

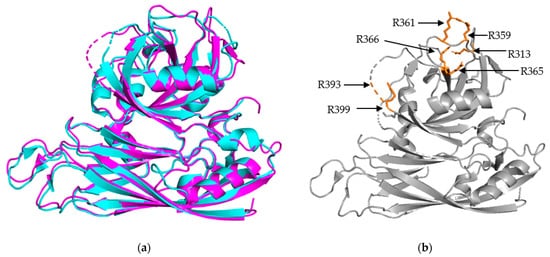

Structural Alignment of HAstV-1 and HAstV-8 core domains. (

) Structural alignment of HAstV-1 aa 80-429 (cyan) and HAstV-8 aa 71-415 (magenta) indicates a high level of structural similarity. (

) Trypsin cleavage sites, labeled in orange, for HAstV-8 (grey) are clustered on the exterior surface of both core domains. R393 is located in a structurally disordered loop, so the arrow is used to indicate its approximate position. Structures adapted from [16][23].

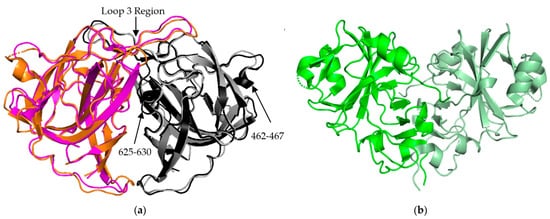

AstV Spike Structures. (

) Structural alignment of HAstV-2 aa 429-645 spike dimer (cyan/black) to HAstV-8 aa 415-646 spike dimer (magenta/grey) indicates a high level of sequence similarity outside of domains from 462-467 and 625-630. The loop 3 region maintains the dimeric state of the spike. (

) Structure of TAstV2 aa 421-724 spike dimer (dark green/light green) shows a significantly different, V-shaped architecture when compared to the human virus structures. Structures adapted from [23][24][25].

3.1. S/P1 Core Domain

The S/P1 core domain structures have been solved for two human astrovirus serotypes, HAstV-8 and HAstV-1 [16][23]. These structures were solved to similar resolutions, 2.15 Å for HAstV-8 and 2.60 Å for HAstV-1. The two structures, aligned in

a, show that the S domain is mostly comprised of β sheets, forming a β barrel jelly roll fold, which is a common structural motif found in viral capsids [26]. The S domain forms the innermost layer of the protein capsid shell. The P1 outer core domain, as the name implies, is oriented away from the capsid core, and sits near the exterior of the virus. It forms trimeric “turret-like” protrusions on the outside, allowing for the arrangement of the P2 spike domain on top (

). The P1 domain is comprised of short β strands (e.g., six for HAstV-1 and seven for HAstV-8) and α helices (e.g., 3 for both HAstV-1 and HAstV-8), with structured/unstructured loops spaced in between. The high percentage of structured loops gives the P1 domain an interwoven layout. When the maturation process is taken into consideration, especially the trypsin-driven transition from VP70 to VP34/27/25, an interesting pattern emerges. In both structures, the trypsin cleavage sites are presented on the edges of the domain, making them accessible to the host proteases (

b) [16][23]. This is a prime example of how the structure can rationalize findings from functional and cell culture studies.

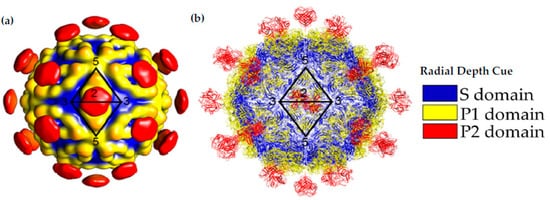

Capsid Structure of the mature HAstV-8 VP34/27/25 Particle. (

) Cryo-electron microscopy map at of resolution of ~25 Å of the mature viral capsid colored by radial depth cue from blue to yellow to red. Dimeric spikes are seen on the 2-fold axis, revealing the 3- and 5-fold axes of the core. (

) HAstV-8 crystal structures for the spike and core modeled into a capsid. The S, P1 and P2 domains are colored in blue, yellow and red, respectively. Adapted from [16][24][27].

3.2. P2 Spike Domain

The P2 spike domain structure has been solved for three human astroviruses, HAstV-1, HAstV-2, HAstV-8 (

Figure 3a) [25,27,28]. Across these three astroviruses, the spike domain consistently forms a globular dimer, resulting in 90 spikes covering the VP70 capsid. When superimposed, HAstV-1 and HAstV-8 spikes show close resemblance, with the structure being mostly made up of a hydrophobic core with six β sheets (

a) [25][27][28]. Across these three astroviruses, the spike domain consistently forms a globular dimer, resulting in 90 spikes covering the VP70 capsid. When superimposed, HAstV-1 and HAstV-8 spikes show close resemblance, with the structure being mostly made up of a hydrophobic core with six β sheets (

a). HAstV-1 has a nearly identical structural similarity to HAstV-8 but was not shown in

Figure 3a for the purpose of clarity. The spike interior interface is primarily driven by loop 3, which extends from the top of the spike from one subunit towards the other subunit. This creates a large surface resulting in a strong dimer interaction as indicated by stable dimer formation when the spike domain was expressed alone [23,24,25]. Most of the structural variability across these three human astroviruses appears to be on the exterior surfaces, such as the presence or absence of α helices in the amino acid 462–467 and 625–630 regions (

a for the purpose of clarity. The spike interior interface is primarily driven by loop 3, which extends from the top of the spike from one subunit towards the other subunit. This creates a large surface resulting in a strong dimer interaction as indicated by stable dimer formation when the spike domain was expressed alone [23][24][25]. Most of the structural variability across these three human astroviruses appears to be on the exterior surfaces, such as the presence or absence of α helices in the amino acid 462–467 and 625–630 regions (

a) [28]. These small differences of sequence and secondary structure can significantly contribute to differences in antibody recognition.

The crystal structure of the turkey astrovirus 2 (TAstV-2) spike has also been determined (

b) [29]. The CPs of

Avastrovirus

subfamily are usually smaller than those of

Mammastrovirus [29,30]. This reduction in size is found throughout the ORF2 sequence, but the majority of the variability occurs in the C-terminal 200–300 amino acids out of the ~700 amino acid sequence that are mapped to the spike domain [31,32]. TAstV2 spike also forms a dimer, but has a V-like shape, fewer β strands, and a number of alpha helixes along the inner dimer interface and the exposed regions, leading to a significantly different spike appearance (

[29][30]. This reduction in size is found throughout the ORF2 sequence, but the majority of the variability occurs in the C-terminal 200–300 amino acids out of the ~700 amino acid sequence that are mapped to the spike domain [31][32]. TAstV2 spike also forms a dimer, but has a V-like shape, fewer β strands, and a number of alpha helixes along the inner dimer interface and the exposed regions, leading to a significantly different spike appearance (

b) [25]. This indicates that while astroviruses across both genera share the same functional role and similar overall structural folds, there could be significant structural and functional differences in the spike domain from strains that have not been studied. This could be especially relevant for the emerging MLB and VA strains of AstV, classified to the

Mammastrovirus

genotype 1 and 2, respectively, that appear to have different pathogenesis than the eight classical human astrovirus serotypes [33]. More investigation into the capsid proteins of avian astroviruses will allow for the establishment of molecular patterns across the two astrovirus genera.

While there have been no new astrovirus structures solved using X-ray crystallography in the last four years, there have been several recent studies using existing structural information to model the evolution of AstV structures [34,35]. A large amount of sequencing data has been collected related to known AstV strains, which can be used to analyze amino acid variations in various regions in existing structures. This approach was taken with HAstV-1 sequences from around the world, which identified six key sites across the VP34/27/25 domains that suggest sub-lineages of the virus. Variability in these key sites also indicate that these regions are under strong selection by host and antibody responses [34]. It is anticipated that novel approaches in structure modeling can be used to predict key differences between classical and emerging strains of human astroviruses and can complement structural studies to better understand antibody responses and functions related to the viral capsid protein.

While there have been no new astrovirus structures solved using X-ray crystallography in the last four years, there have been several recent studies using existing structural information to model the evolution of AstV structures [34][35]. A large amount of sequencing data has been collected related to known AstV strains, which can be used to analyze amino acid variations in various regions in existing structures. This approach was taken with HAstV-1 sequences from around the world, which identified six key sites across the VP34/27/25 domains that suggest sub-lineages of the virus. Variability in these key sites also indicate that these regions are under strong selection by host and antibody responses [34]. It is anticipated that novel approaches in structure modeling can be used to predict key differences between classical and emerging strains of human astroviruses and can complement structural studies to better understand antibody responses and functions related to the viral capsid protein.

References

- Donato, C.; Vijaykrishna, D. The Broad Host Range and Genetic Diversity of Mammalian and Avian Astroviruses. Viruses 2017, 9, 102.

- Johnson, C.; Hargest, V.; Cortez, V.; Meliopoulos, V.A.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Astrovirus Pathogenesis. Viruses 2017, 9, 22.

- Caballero, S.; Guix, S.; El-Senousy, W.M.; Calicó, I.; Pintó, R.M.; Bosch, A. Persistent Gastroenteritis in Children Infected with Astrovirus: Association with Serotype-3 Strains. J. Med. Virol. 2003, 71, 245–250.

- Cordey, S.; Brito, F.; Vu, D.-L.; Turin, L.; Kilowoko, M.; Kyungu, E.; Genton, B.; Zdobnov, E.M.; D’Acremont, V.; Kaiser, L. Astrovirus VA1 Identified by Next-Generation Sequencing in a Nasopharyngeal Specimen of a Febrile Tanzanian Child with Acute Respiratory Disease of Unknown Etiology. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2016, 5, e67.

- Finkbeiner, S.R.; Le, B.-M.; Holtz, L.R.; Storch, G.A.; Wang, D. Detection of Newly Described Astrovirus MLB1 in Stool Samples from Children. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2009, 15, 441–444.

- Kumthip, K.; Khamrin, P.; Ushijima, H.; Maneekarn, N. Molecular Epidemiology of Classic, MLB and VA Astroviruses Isolated from <5 Year-Old Children with Gastroenteritis in Thailand, 2011–2016. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 65, 373–379.

- Blomström, A.-L.; Widén, F.; Hammer, A.-S.; Belák, S.; Berg, M. Detection of a Novel Astrovirus in Brain Tissue of Mink Suffering from Shaking Mink Syndrome by Use of Viral Metagenomics. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 4392–4396.

- Bulbule, N.R.; Mandakhalikar, K.D.; Kapgate, S.S.; Deshmukh, V.V.; Schat, K.A.; Chawak, M.M. Role of Chicken Astrovirus as a Causative Agent of Gout in Commercial Broilers in India. Avian Pathol. 2013, 42, 464–473.

- Schlottau, K.; Schulze, C.; Bilk, S.; Hanke, D.; Höper, D.; Beer, M.; Hoffmann, B. Detection of a Novel Bovine Astrovirus in a Cow with Encephalitis. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2016, 63, 253–259.

- Monroe, S.S.; Jiang, B.; Stine, S.E.; Koopmans, M.; Glass, R.I. Subgenomic RNA Sequence of Human Astrovirus Supports Classification of Astroviridae as a New Family of RNA Viruses. J. Virol. 1993, 67, 3611–3614.

- Méndez, E.; Aguirre-Crespo, G.; Zavala, G.; Arias, C.F. Association of the Astrovirus Structural Protein VP90 with Membranes Plays a Role in Virus Morphogenesis. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 10649–10658.

- Guix, S.; Bosch, A.; Ribes, E.; Dora Martínez, L.; Pintó, R.M. Apoptosis in Astrovirus-Infected CaCo-2 Cells. Virology 2004, 319, 249–261.

- Méndez, E.; Salas-Ocampo, E.; Arias, C.F. Caspases Mediate Processing of the Capsid Precursor and Cell Release of Human Astroviruses. J. Virol. 2004, 78, 8601–8608.

- Geigenmüller, U.; Ginzton, N.H.; Matsui, S.M. Studies on Intracellular Processing of the Capsid Protein of Human Astrovirus Serotype 1 in Infected Cells. J. Gen. Virol. 2002, 83, 1691–1695.

- Richard, A.; Tulasne, D. Caspase Cleavage of Viral Proteins, Another Way for Viruses to Make the Best of Apoptosis. Cell Death Dis. 2012, 3, e277.

- Toh, Y.; Harper, J.; Dryden, K.A.; Yeager, M.; Arias, C.; Mendez, E.; Tao, Y.J. Crystal Structure of the Human Astrovirus Capsid Protein. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 9008–9017.

- Aguilar-Hernández, N.; López, S.; Arias, C.F. Minimal Capsid Composition of Infectious Human Astrovirus. Virology 2018, 521, 58–61.

- del Banos-Lara, M.R.; Méndez, E. Role of Individual Caspases Induced by Astrovirus on the Processing of Its Structural Protein and Its Release from the Cell through a Non-Lytic Mechanism. Virology 2010, 401, 322–332.

- Moser, L.A.; Carter, M.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Astrovirus Increases Epithelial Barrier Permeability Independently of Viral Replication. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 11937–11945.

- Méndez, E.; Fernández-Luna, T.; López, S.; Méndez-Toss, M.; Arias, C.F. Proteolytic Processing of a Serotype 8 Human Astrovirus ORF2 Polyprotein. J. Virol. 2002, 76, 7996–8002.

- Bass, D.M.; Qiu, S. Proteolytic Processing of the Astrovirus Capsid. J. Virol. 2000, 74, 1810–1814.

- Drozdetskiy, A.; Cole, C.; Procter, J.; Barton, G.J. JPred4: A Protein Secondary Structure Prediction Server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, W389–W394.

- York, R.L.; Yousefi, P.A.; Bogdanoff, W.; Haile, S.; Tripathi, S.; DuBois, R.M. Structural, Mechanistic, and Antigenic Characterization of the Human Astrovirus Capsid. J. Virol. 2016, 90, 2254–2263.

- Dong, J.; Dong, L.; Méndez, E.; Tao, Y. Crystal Structure of the Human Astrovirus Capsid Spike. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 12681–12686.

- DuBois, R.M.; Freiden, P.; Marvin, S.; Reddivari, M.; Heath, R.J.; White, S.W.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Crystal Structure of the Avian Astrovirus Capsid Spike. J. Virol. 2013, 87, 7853–7863.

- Khayat, R.; Johnson, J.E. Pass the Jelly Rolls. Structure 2011, 19, 904–906.

- Dryden, K.A.; Tihova, M.; Nowotny, N.; Matsui, S.M.; Mendez, E.; Yeager, M. Immature and Mature Human Astrovirus: Structure, Conformational Changes, and Similarities to Hepatitis E Virus. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 422, 650–658.

- Bogdanoff, W.A.; Campos, J.; Perez, E.I.; Yin, L.; Alexander, D.L.; DuBois, R.M. Structure of a Human Astrovirus Capsid-Antibody Complex and Mechanistic Insights into Virus Neutralization. J. Virol. 2017, 91.

- Bosch, A.; Pintó, R.M.; Guix, S. Human Astroviruses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 1048–1074.

- Koci, M.D.; Schultz-Cherry, S. Avian Astroviruses. Avian Pathol. 2002, 31, 213–227.

- De Benedictis, P.; Schultz-Cherry, S.; Burnham, A.; Cattoli, G. Astrovirus Infections in Humans and Animals—Molecular Biology, Genetic Diversity, and Interspecies Transmissions. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2011, 11, 1529–1544.

- Smyth, V.J.; Todd, D.; Trudgett, J.; Lee, A.; Welsh, M.D. Capsid Protein Sequence Diversity of Chicken Astrovirus. Avian Pathol. 2012, 41, 151–159.

- Lum, S.H.; Turner, A.; Guiver, M.; Bonney, D.; Martland, T.; Davies, E.; Newbould, M.; Brown, J.; Morfopoulou, S.; Breuer, J.; et al. An Emerging Opportunistic Infection: Fatal Astrovirus (VA1/HMO-C) Encephalitis in a Pediatric Stem Cell Transplant Recipient. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2016, 18, 960–964.

- De Grazia, S.; Lanave, G.; Bonura, F.; Urone, N.; Cappa, V.; Li Muli, S.; Pepe, A.; Gellért, A.; Banyai, K.; Martella, V.; et al. Molecular Evolutionary Analysis of Type-1 Human Astroviruses Identifies Putative Sites under Selection Pressure on the Capsid Protein. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2018, 58, 199–208.

- De Nova-Ocampo, M.; Soliman, M.C.; Espinosa-Hernández, W.; Velez-del Valle, C.; Salas-Benito, J.; Valdés-Flores, J.; García-Morales, L. Human Astroviruses: In Silico Analysis of the Untranslated Region and Putative Binding Sites of Cellular Proteins. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2018.