Ovarian high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSCs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases. They include fallopian-tube-epithelium (FTE)-derived and ovarian-surface-epithelium (OSE)-derived tumors. The risk/protective factors suggest that the etiology of HGSCs is multifactorial.

- ovarian cancer

- high-grade serous carcinoma

- carcinogenesis

- molecular alterations

Note: The following contents are extract from your paper. The entry will be online only after author check and submit it.

1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the most lethal gynecological malignancy. Epithelial ovarian cancers (EOCs) are a heterogeneous group of diseases and can be divided into five main types, based on histopathology and molecular genetics [1]: high-grade serous, low-grade serous, endometrioid, clear cell, and mucinous tumors. These tumors may be classified into type I and II tumors. Type I tumors include endometriosis-related tumors (endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas), low-grade serous carcinoma, and mucinous carcinoma. Type II tumors are composed of high-grade serous carcinomas, for the most part [2]. Although this classification conflicts with recent molecular insights into the etiology of EOCs [3], type II tumors that also include carcinosarcomas could be classed together.

High-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) is the most common and lethal subtype of EOC, as most women with HGSC are diagnosed at a late stage, when achieving a cure is rare [4]. The vast majority of serous carcinomas are high-grade tumors [5]. To develop an effective method for prevention and early detection, elucidation of carcinogenesis is essential. Recently, our understanding of the origins and pathogenesis of HGSC has substantially progressed through whole genome and bioinformatic analyses.

2. Carcinogenic Hypotheses and Risk/Protective Factors

2.1. Incessant Ovulation

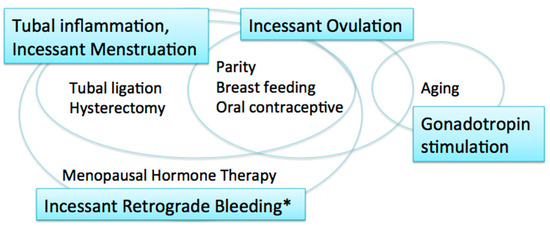

EOCs were traditionally thought to arise from the ovarian surface epithelium (OSE). The OSE is the pelvic mesothelium that overlies the ovary and lines ovarian epithelial inclusion cysts, and is derived from the coelomic epithelium [6][7]. The risk/protective factors for EOCs include parity, breast-feeding, and oral contraceptive use; all of these factors reduce ovarian cancer risk [8] (

). These reproductive and hormonal factors are associated with ovulation suppression. Thus, the risk of EOC is thought to be associated with the number of ovulatory cycles.

Carcinogenic hypotheses and risk/protective factors. * including menstruation and postmenopausal bleeding.

The incessant ovulation hypothesis was proposed by Fathalla in 1971 based on these observations [9]. This hypothesis proposes that recurrent damage and repair of the OSE from repeated ovulation increase the risk of cell damage and subsequent neoplastic transformation. A study showed that a higher number of ovulatory cycles may be associated with increased amounts of DNA damage [10].

2.2. Gonadotropin Stimulation

The majority of women with ovarian cancer present in the postmenopausal period, when pituitary gonadotropin levels are elevated. The gonadotropin stimulation hypothesis proposes that high gonadotropin levels can have an effect on OSE cells and promote carcinogenesis [11][12]. Gonadotropins that persist in high levels for many years after menopause may stimulate the OSE, in which gonadotropin receptors are expressed, and OSE cells may subsequently undergo malignant transformation [12]. Surges of gonadotropins that initiate each ovulation may also play a role in carcinogenesis; thus, the incessant ovulation and gonadotropin hypotheses are interrelated.

2.3. Tubal Inflammation

These two hypotheses, however, have limitations. If the number of lifetime ovulatory cycles and exposure to high levels of gonadotropins are associated with EOC development, fertility treatment might increase the risk of EOC via the multiple ovulations stimulated by gonadotropins, specifically luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH). In fact, studies suggest that there is no significant relationship between in vitro fertilization treatment using gonadotropin stimulation and subsequent risk of EOC [13][14]. In addition, as the ovulatory rupture sites appear to be random, the repeated rupture and repair that occurs with each ovulation should not affect the same population of surface epithelial cells [15]. Furthermore, neither the incessant ovulation nor gonadotropin stimulation hypotheses explains the protective effect of tubal ligation and hysterectomy on the development of EOC [16].

The fallopian tube, in particular the fimbriae, emerged as another site of origin based on findings related to prophylactic surgery for ovarian cancer risk reduction in women with genetic predisposition to the disease [17]. Based on these observations, the tubal inflammation hypothesis was proposed by Salvador [7]. Chronic inflammation is known to be a risk for cancer. The fallopian tube is regularly exposed to a variety of inflammatory agents, and can show signs of acute and chronic inflammation, through the process of retrograde bleeding from the endometrial cavity during menstruation. Infection also induces inflammation in the fallopian tube [7]. Chlamydia trachomatis infection may be associated with serous carcinogenesis [18].

2.4. Incessant Menstruation

The incessant menstruation hypothesis, proposed by Vercellini [16], also explains why ovarian cancer risk is decreased by tubal ligation and ovulation suppression. In this theory, pathogenesis of endometriosis-associated carcinomas, specifically endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas, as well as serous carcinomas, can be explained. In serous carcinomas, retrograde menstruation from the endometrial cavity into the Douglas pouch is the causative mechanism that generates fallopian tube inflammation [7][16]. The incessant menstruation hypothesis explains ovarian cancer risk well in the premenopausal period. However, in postmenopausal women, another risk factor is related to ovarian carcinogenesis, that is, menopausal hormone therapy (MHT).

2.5. Incessant Retrograde Bleeding

Incessant retrograde bleeding is an expansion of the concept of incessant menstruation and may explain more accurately the etiology of HGSCs in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women [19]. Some types of MHT, also called hormone replacement therapy, increase ovarian cancer risk. The risk of serous ovarian cancer differs by regimen of MHT. Its risk in women with intact uteri is increased with the use of estrogen alone, and estrogen with sequentially added progestin [20][21]. Both regimens cause endometrial bleeding. In contrast, serous ovarian cancer risk is not altered by the use of continuous estrogen and progestin, which results in endometrial atrophy with bleeding cessation [19][21]. Thus, MHT regimens that cause endometrial bleeding are associated with an increased risk of serous ovarian carcinoma.

3. Sites of Origin of HGSCs

Although the dominant site of origin for HGSCs is the distal fallopian tube (fimbriae) [17][22], HGSCs can also arise from the ovary [23][24][25][26][27]. In experimental models, HGSCs developed from both the fallopian tube and ovary with inactivation of a few genes [26][28][29][30]. Cancer may originate from the transition of stem cells, as the acquisition of multiple mutagenic events can occur in long-lived stem cells that are capable of self-renewal [31], and stem cells can be found both in the fallopian tube and ovary, in particular in the distal fallopian tube and in the transition area between the OSE, mesothelium, and tubal epithelium [23][32][33].

3.1. Fallopian Tube Epithelium

A substantial percentage (60–88%) of HGSCs originate in the fallopian tube [17][22][25][34][35], both in women with

mutations and in sporadic cases [2][17][36]. The molecular profile and immunophenotype of HGSCs are more closely related to the FTE than OSE [22][37][38]. Although fallopian tube epithelial secretory cells are believed to give rise to HGSCs [28], ciliated cells may be another cell-of-origin in the fallopian tube epithelium (FTE) [26].

In the FTE, p53 signatures and serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma (STIC), both of which are intraepithelial lesions associated with HGSC, can be identified. The p53 signature is a focus of strong p53 immunostaining in benign tubal mucosa [39] and harbors

mutations and evidence of DNA damage [40]. Telomere shortening occurs in p53 signatures, suggesting that the p53 signature is the earliest precancer lesion [41]. However, the p53 signature may not always be a preneoplastic lesion of HGSC, as p53 overexpression has been found to be common both in

carriers and in noncarriers who underwent surgery for benign disease or RRSO [42]. STIC, which is composed of secretory cells showing significant atypia, architectural alterations, a high proliferative index, and strong p53 immunostaining [43], is a putative precursor lesion of HGSC. Identical somatic

mutations have been detected in the majority of pairs of STIC and concurrent HGSCs [44]. However, not all HGSCs may arise from STIC lesions, even in high-risk women [45]. STIC was observed only in 11–61% (mean 31%) of HGSCs [46], and some STICs are actually metastases from HGSCs, rather than HGSC precursors [47]. Additionally, a subset of serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasias, including STIC, are an intraepithelial metastasis from a contralateral serous tubal intraepithelial neoplasia [48]. STICs and serous tubal intraepithelial lesions (STILs), which are intermediate lesions between the p53 signature and STIC, may not share the protective factors that are associated with HGSC [49]. The development of STICs may be related to random mutations occurring in target cancer drivers, including

[49]. Thus, many potential precursor or premalignant lesions do not advance to malignant tumors or lethal malignancies [45].

3.2. Ovarian Surface Epithelium

The OSE is another site of origin for HGSCs. Ovarian carcinoma in situ has been identified in ovaries removed in risk-reducing oophorectomies in women with a germline

mutation [50]. A literature review of microscopic ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal tumors in

mutation carriers showed that 60.5% were confined to the fallopian tube only, whereas 21.1% and 2.6% involved only the ovary and only the peritoneum, respectively [35]. Ovarian epithelial inclusion cysts are considered to be a possible site of origin of HGSCs. HGSCs may frequently arise within epithelial inclusion cysts, but not the surface epithelium itself [51]. A dysplastic precursor lesion within epithelial inclusion cysts, showing accumulation of p53, precedes carcinoma development. Recently, the concept of precursor escape has been postulated. Cells from early precursors, such as early serous proliferations, are shed from the fallopian tube and undergo subsequent malignant transformation on the surface of the ovary and peritoneum [52]. There are two known types of ovarian inclusion cysts; one is positive for PAX8 (mullerian marker), and the other is positive for calretinin (mesothelial marker) [53]. However, they may not represent FTE-derived and OSE-derived cysts, as many PAX8-positive cells arise from metaplasia of OSE-derived inclusion cysts [54]. In a mouse model, ectopic tubal-type epithelium (endosalpingiosis) in the ovary did not likely arise as a consequence of detachment and implantation of the tubal epithelium [55].

FTE-derived and OSE-derived HGSCs are different in their pattern of metastasis, transcriptome, and response to chemotherapy [26]. FTE-derived tumors have a greater propensity to disseminate, whereas OSE-derived tumors form large, solitary lesions, with less frequent metastasis [26]. OSE-derived HGSC may have a long latent period and a poor prognosis compared to FTE-derived HGSC [24][25]. The poorer prognosis associated with OSE-derived HGSC may partly be explained by its mesenchymal characteristics. OSE cells have a dual epithelia–mesenchymal phenotype [56], and in the mouse ovaries leiomyosarcoma developed with inactivation of

References

- Prat, J.; D’Angelo, E.; Espinosa, I. Ovarian carcinomas: At least five different diseases with distinct histological features and molecular genetics. Hum. Pathol. 2018, 80, 11–27.

- Kurman, R.J.; Shih, I.M. The dualistic model of ovarian carcinogenesis: Revisited, revised, and expanded. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 733–747.

- Salazar, C.; Campbell, I.G.; Gorringe, K.L. When Is “Type I” Ovarian Cancer Not “Type I”? Indications of an Out-Dated Dichotomy. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 654.

- Bowtell, D.D. The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2010, 10, 803–808.

- Bodurka, D.C.; Deavers, M.T.; Tian, C.; Sun, C.C.; Malpica, A.; Coleman, R.L.; Lu, K.H.; Sood, A.K.; Birrel, M.J.; Ozols, R.; et al. Reclassification of serous ovarian carcinoma by a 2-tier system. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer 2012, 119, 3087–3094.

- Auersperg, N.; Woo, M.M.; Gilks, C.B. The origin of ovarian carcinomas: A developmental view. Gynecol. Oncol. 2008, 110, 452–454.

- Salvador, S.; Gilks, B.; Köbel, M.; Huntsman, D.; Rosen, B.; Miller, D. The fallopian tube: Primary site of most pelvic high-grade serous carcinomas. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2009, 19, 58–64.

- Menon, U.; Karpinskyj, C.; Gentry-Maharaj, A. Ovarian Cancer Prevention and Screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2018, 131, 909–927.

- Fathalla, M.F. Incessant ovulation—A factor in ovarian neoplasia? Lancet 1971, 2, 163.

- Schildkraut, J.M.; Bastos, E.; Berchuck, A. Relationship between lifetime ovulatory cycles and overexpression of mutant p53 in epithelial ovarian cancer. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 1997, 89, 932–938.

- Stadel, B.V. The etiology and prevention of ovarian cancer. Am. J. Obstet Gynecol. 1975, 123, 772–774.

- Mertens-Walker, I.; Baxter, R.C.; Marsh, D.J. Gonadotropin signalling in epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Lett. 2012, 324, 152–159.

- Siristatidis, C.T.N.; Sergentanis, P.; Kanavidis, P.; Trivella, M.; Sotiraki, M.; Marvromatis, I.; Psaltopoulou, T.; Skalkidou, A.; Petridou, E.T. Controlled ovarian hyperstimulation for IVF: Impact on ovarian, endometrial and cervical cancer—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod Update 2013, 19, 105–123.

- Gronwald, J.; Glass, K.; Rosen, B.; Karlan, B.; Tung, N.; Neuhausen, S.L.; Moller, P.; Ainsworth, P.; Sun, P.; Narod, S.A.; et al. Treatment of infertility does not increase the risk of ovarian cancer among women with a BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation. Fertil Steril 2016, 105, 781–785.

- Smith, E.R.; Xu, X.X. Etiology of epithelial ovarian cancer: A cellular mechanism for the role of gonadotropins. Gynecol. Oncol. 2003, 91, 1–2.

- Vercellini, P.; Crosignani, P.; Somigliana, E.; Vigano, P.; Buggio, L.; Bolis, G.; Fedele, L. The incessant menstruation’ hypothesis: A mechanistic ovarian cancer model with implications for prevention. Hum. Reprod 2011, 26, 2262–2273.

- Crum, C.P.; Drapkin, R.; Kindelberger, D.; Medeiros, F.; Miran, A.; Lee, Y. Lessons from BRCA: The tubal fimbria emerges as an origin for pelvic serous cancer. Clin. Med. Res. 2007, 5, 35–44.

- Idahl, A.; Le Cornet, C.; Maldonado, S.G.; Waterboer, T.; Bender, N.; Tjønneland, A.; Hansen, L.; Boutron-Ruault, M.-C.; Fournier, A.; Kvaskoff, M.; et al. Serologic markers of Chlamydia trachomatis and other sexually transmitted infections and subsequent ovarian cancer risk: Results from the EPIC cohort. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 2042–2052.

- Otsuka, I.; Matsuura, T. Screening and prevention for high-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary based on carcinogenesis—Fallopian tube- and ovarian-derived tumors and incessant retrograde bleeding. Diagnostics 2020, 10, 120.

- Riman, T.; Dickman, P.W.; Nilsson, S.; Correia, N.; Nordlinder, H.; Magnusson, C.M.; Weiderpass, E.; Persson, I.R. Hormone replacement therapy and the risk of invasive epithelial ovarian cancer in Swedish women. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 2002, 94, 497–504.

- Koskela-Niska, V.; Riska, A.; Lyytinen, H.; Pukkala, E.; Ylikorkala, O. Primary fallopian tube carcinoma risk in users of postmenopausal hormone therapy in Finland. Gynecol. Oncol. 2012, 126, 241–244.

- Ducie, J.; Dao, F.; Considine, M.; Olvera, N.; Shaw, P.A.; Kurman, R.J.; Shih, I.M.; Soslow, R.A.; Cope, L.; Levine, D.A. Molecular analysis of high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma with and without associated serous tubal intra-epithelial carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 990.

- Ng, A.; Tan, S.; Singh, G.; Rizk, P.; Swathi, Y.; Tan, T.Z.; Huang, R.Y.; Leushacke, M.; Barker, N. Lgr5 marks stem/progenitor cells in ovary and tubal epithelia. Nat. Cell. Biol. 2014, 16, 745–757.

- Coscia, F.; Watters, K.M.; Curtis, M.; Eckert, M.A.; Chiang, C.Y.; Tyanova, S.; Montag, A.; Lastra, R.R.; Lengyel, E.; Mann, M. Integrative proteomic profiling of ovarian cancer cell lines reveals precursor cell associated proteins and functional status. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12645.

- Hao, D.; Li, J.; Jia, S.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Di, L.-J. Integrated analysis reveals tubal- and ovarian-originated serous ovarian cancer and predicts differential therapeutic responses. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017, 23, 7400–7411.

- Zhang, S.; Dolgalev, I.; Zhang, T.; Ran, H.; Levine, D.A.; Neel, B.G. Both fallopian tube and ovarian surface epithelium are cells-of-origin for high-grade serous ovarian carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5367.

- Geistlinger, L.; Oh, S.; Ramos, M.; Schiffer, L.; Larue, R.S.; Henzler, C.M.; Munro, S.A.; Daughters, C.; Nelson, A.C.; Winterhoff, B.J.; et al. Multiomic Analysis of Subtype Evolution and Heterogeneity in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2020, 80, 4335–4345.

- Karst, A.M.; Levanon, K.; Drapkin, R. Modeling high-grade serous ovarian carcinogenesis from the fallopian tube. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 7547–7552.

- Szabova, L.; Yin, C.; Bupp, S.; Guerin, T.M.; Schlomer, J.L.; Householder, D.B.; Baran, M.L.; Yi, M.; Song, Y.; Sun, W.; et al. Perturbation of Rb, p53, and Brca1 or Brca2 cooperate in inducing metastatic serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2012, 72, 4141–4153.

- Zhai, Y.; Wu, R.; Kuick, R.; Sessine, M.S.; Schulman, S.; Green, M.; Fearon, E.R.; Cho, K.R. High-grade serous carcinomas arise in the mouse oviduct via defects linked to the human disease. J. Pathol. 2017, 243, 16–25.

- Reya, T.; Morrison, S.J.; Clarke, M.F.; Weissman, I.L. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 2001, 414, 105–111.

- Paik, D.Y.; Janzen, D.M.; Schafenacker, A.M.; Velasco, V.S.; Shung, M.S.; Chieng, D.; Huang, J.; Witte, O.N.; Memarzadeh, S. Stem-like epithelial cells are concentrated in the distal end of the fallopian tube: A site for injury and serous cancer initiation. Stem Cells 2012, 30, 2487.

- Flesken-Nikitin, A.; Hwang, C.I.; Cheng, C.Y.; Michurina, T.V.; Enikolopov, G.; Nikitin, A.Y. Ovarian surface epithelium at the junction area contains a cancer-prone stem cell niche. Nature 2013, 495, 241–245.

- Crum, C.P. Intercepting pelvic cancer in the distal fallopian tube: Theories and realities. Mol. Oncol. 2009, 3, 165–170.

- Yates, M.S.; Meyer, L.A.; Deavers, M.T.; Daniels, M.S.; Keeler, E.R.; Mok, S.C.; Gershenson, D.M.; Lu, K.H. Microscopic and early-stage ovarian cancers in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers: Building a model for early BRCA-associated tumorigenesis. Cancer Prev. Res. 2011, 4, 463–470.

- Gilks, C.B.; Irving, J.; Köbel, M.; Lee, C.; Singh, N.; Wilkinson, N.; McCluggage, W.G. Incidental Nonuterine High-grade Serous Carcinomas Arise in the Fallopian Tube in Most Cases Further Evidence for the Tubal Origin of High-grade Serous Carcinomas. Am. J. Surg Pathol. 2015, 39, 357–364.

- Xiang, L.; Rong, G.; Zhao, J.; Wang, Z.; Shi, F. Identification of candidate genes associated with tubal origin of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 2018, 15, 7769–7775.

- Beirne, J.P.; McArt, D.G.; Roddy, A.; McDermott, C.; Ferris, J.; Buckley, N.E.; Coulter, P.; McCabe, N.; Eddie, S.I.; McCluggage, W.G.; et al. Defining the molecular evolution of extrauterine high grade serous carcinoma. Gynecol. Oncol. 2019, 155, 305–317.

- Lee, Y.; Miron, A.; Drapkin, R.; Nucci, M.R.; Medeiros, F.; Saleemuddin, A.; Garber, J.; Birch, C.; Mou, H.; Gordon, R.W.; et al. A candidate precursor to serous carcinoma that originates in the distal fallopian tube. J. Pathol. 2007, 211, 26–35.

- Xian, W.; Miron, A.; Roh, M.; Semmel, D.R.; Yassin, Y.; Garber, J.; Oliva, E.; Goodman, A.; Mehra, K.; Berkowitz, R.S.; et al. The Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS): A model for the initiation of p53 signatures in the distal Fallopian tube. J. Pathol. 2010, 220, 17–23.

- Asaka, S.; Davis, C.; Lin, S.-F.; Wang, T.-L.; Heaphy, C.M.; Shih, I.-M. Analysis of Telomere Lengths in p53 Signatures and Incidental Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Carcinomas without Concurrent Ovarian Cancer. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2019, 43, 1083–1091.

- Mehra, K.K.; Chang, M.C.; Folkins, A.K.; Raho, C.J.; Lima, J.F.; Yuan, L.; Mehrad, M.; Tworoger, S.S.; Crum, C.P.; Saleemuddin, A. The impact of tissue block sampling on the detection of p53 signatures in fallopian tubes from women with BRCA 1 or 2 mutations (BRCA+) and controls. Mod. Pathol. 2011, 24, 152–156.

- Horn, L.C.; Kafkova, S.; Leonhardt, K.; Kellner, C.; Einenkel, J. Serous tubal in situ carcinoma (STIC) in primary peritoneal serous carcinomas. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2013, 32, 339–344.

- Kuhn, E.; Kurman, R.J.; Vang, R.; Sehdev, A.S.; Han, G.; Soslow, R.; Wang, T.L.; Shih, I.M. TP53 mutations in serous tubal intraepithelial carcinoma and concurrent pelvic high-grade serous carcinoma—Evidence supporting the clonal relationship of the two lesions. J. Pathol. 2012, 226, 421–426.

- Kim, J.; Park, E.Y.; Kim, O.; Schilder, J.M.; Coffey, D.M.; Cho, C.H.; Bast, R.C., Jr. Cell Origins of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 433.

- Chen, F.; Gaitskell, K.; Garcia, M.J.; Albukhari, A.; Tsaltas, J.; Ahmed, A.A. Serous tubal intraepithelial carcinomas associated with high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas: A systematic review. BJOG 2017, 124, 872–878.

- Eckert, M.A.; Pan, S.; Hernandez, K.M.; Loth, R.M.; Andrade, J.; Volchenboum, S.L.; Faber, P.; Montag, A.; Lastra, R.; Peter, M.E.; et al. Genomics of ovarian cancer progression reveals diverse metastatic trajectories including intraepithelial metastasis to the fallopian tube. Cancer Discov. 2016, 6, 1342–1351.

- Meserve, E.E.; Strickland, K.C.; Miron, A.; Soong, T.R.; Campbell, F.; Howitt, B.E.; Crum, C.P. Evidence of a Monoclonal Origin for Bilateral Serous Tubal Intraepithelial Neoplasia. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2019, 38, 443–448.

- Visvanathan, K.; Shaw, P.; May, B.J.; Bahadirli-Talbott, A.; Kaushiva, A.; Risch, H.; Narod, S.; Wang, T.L.; Parkash, V.; Vang, R.; et al. Fallopian Tube Lesions in Women at High Risk for Ovarian Cancer: A. Multicenter Study. Cancer Prev. Res. 2018, 11, 697–706.

- Werness, B.A.; Parvatiyar, P.; Ramus, S.J.; Whittemore, A.S.; Garlinghouse-Jones, K.; Oakley-Girvan, I.; DiCioccio, R.A.; Wiest, J.; Tsukada, Y.; Ponder, B.A.J.; et al. Ovarian carcinoma in situ with germline BRCA1 mutation and loss of heterozygosity at BRCA1 and TP53. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2000, 92, 1088–1091.

- Pothuri, B.; Leitao, M.M.; Levine, D.A.; Viale, A.; Olshen, A.B.; Arroyo, O.; Bogomolniy, F.; Olvera, N.; Lin, O.; Soslow, R.A.; et al. Genetic analysis of the early natural history of epithelial ovarian carcinoma. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10358.

- Soong, T.R.; Howitt, B.E.; Miron, A.; Horowitz, N.S.; Campbell, F.; Feltmate, C.M.; Muto, M.G.; Berkowitz, R.S.; Nucci, M.R.; Xian, W.; et al. Evidence for lineage continuity between early serous proliferations (ESPs) in the Fallopian tube and disseminated high-grade serous carcinomas. J. Pathol. 2018, 246, 344–351.

- Banet, N.; Kurman, R.J. Two Types of Ovarian Cortical Inclusion Cysts: Proposed Origin and Possible Role in Ovarian Serous Carcinogenesis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 2015, 34, 3–8.

- Park, K.J.; Patel, P.; Linkov, I.; Jotwani, A.; Kauff, N.; Pike, M.C. Observations on the origin of ovarian cortical inclusion cysts in women undergoing risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy. Histopathology 2018, 72, 766–776.

- Wang, Y.; Sessine, M.S.; Zhai, Y.; Tipton, C.; McCool, K.; Kuick, R.; Connolly, D.C.; Fearon, E.R.; Cho, K.R. Lineage tracing suggests that ovarian endosalpingiosis does not result from escape of oviductal epithelium. J. Pathol. 2019, 249, 206–214.

- Auersperg, N.; Wong, A.S.; Choi, K.C.; Kang, S.K.; Leung, P.C. Ovarian surface epithelium: Biology, endocrinology, and pathology. Endocr. Rev. 2001, 22, 255–288.

- Quinn, B.A.; Brake, T.; Hua, X.; Baxter-Jones, K.; Litwin, S.; Ellenson, L.H.; Connolly, D.C. Induction of ovarian leiomyosarcomas in mice by conditional inactivation of Brca1 and p53. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e8404.

- Murakami, R.; Matsumura, N.; Mandai, M.; Yoshihara, K.; Tanabe, H.; Nakai, H.; Yamanoi, K.; Abiko, K.; Yoshioka, Y.; Hamanishi, J.; et al. Establishment of a Novel Histopathological Classification of High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma Correlated with Prognostically Distinct Gene Expression Subtypes. Am. J. Pathol. 2016, 186, 1103–1113.