Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are membranous structures, which are secreted by almost every cell type analyzed so far. In addition to their importance for cell-cell communication under physiological conditions, EVs are also released during pathogenesis and mechanistically contribute to this process. Here we summarize their functional relevance in asthma, one of the most common chronic non-communicable diseases. Asthma is a complex persistent inflammatory disorder of the airways characterized by reversible airflow obstruction and, from a long-term perspective, airway remodeling. Overall, mechanistic studies summarized here indicate the importance of different subtypes of EVs and their variable cargoes in the functioning of the pathways underlying asthma, and show some interesting potential for the development of future therapeutic interventions. Association studies in turn demonstrate a good diagnostic potential of EVs in asthma.

- airway

- allergy

- asthma

- epigenetic(-s)

- exosome

1. Introduction

Chronic non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are inflammatory conditions, which are not caused by infectious agents (e.g., bacteria, viruses, parasites). To name a few, these diseases include respiratory disorders such as asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), chronic inflammatory bowel diseases, cardiovascular disorders such as coronary artery disease/ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease or stroke, all based on atherosclerosis, inflammatory disease conditions in the skin (e.g., atopic dermatitis, psoriasis), metabolic diseases such as obesity, metabolic syndrome, and diabetes, different forms of cancer, adverse mental outcomes, etc. Especially after the development of effective prevention (vaccines) and treatment (e.g., antibiotics) options against infectious diseases over the last decades, NCDs became the most significant cause of death in the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), in 2019 the three top causes of death in the World were ischemic heart disease accounting for about 9 million, stroke for more than 6 million deaths, and COPD for more than 3 million deaths in this single year only [1]. For comparison, as of mid-April 2021, the worldwide number of COVID-19-related deaths since the very beginning of the pandemic was approaching 3 million [2]. The burden of NCDs is high in western countries and still rising, in particular in less developed areas [3][4][5][6]. To effectively face this challenge, novel diagnostic and therapeutic approaches should be established based on the growing knowledge on pathobiological mechanisms underlying the development and the clinical course of NCDs.

This specifically applies also to asthma as one of the most prominent NCDs, for which, despite substantial progress, current diagnostic and therapeutic approaches remain suboptimal. One of the major reasons behind this is the heterogeneity of asthma, with a complex etiology and multiple clinical representations, requiring the development of stratified diagnosis and treatment strategies [7][8][9][10]. These can only be achieved on the basis of novel cellular and molecular insights based on innovative methods. In this review, we summarize the current knowledge on extracellular vesicle (EV)-mediated cell-cell communication obtained in the context of pathobiology and clinical pathology of asthma.

2. Extracellular Vesicles and Asthma: Cellular Level

2.1. Airway Epithelial Cells and Fibroblasts

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterized by recurrent symptoms of varying intensity and severity, including wheezing, shortness of breath, cough, feeling of tightness in the chest, and others. The symptoms of asthma are underlain by reversible airway obstruction resulting from easily triggered bronchospasm and enhanced mucus secretion. In a longer perspective, disease progression is associated with, or rather results from, airway remodeling including changes in structural cell composition and extracellular fibrosis [11][12][13][14].

Clinically, asthma is a very heterogeneous disorder with considerable differences in the symptomatology, factors triggering exacerbations, severity, time of onset, demographics, body weight, and other features. Characteristic clinical representations of asthma form so-called phenotypes that are associated with a variety of distinct pathomechanisms named endotypes. Several endotypes have been proposed, which can be roughly grouped into those related to T helper cell type-2 (Th2) and those related to non-Th2 (e.g., Th1/Th17) immune mechanisms. Since it became evident that Th cytokines can be secreted also by other cell types, e.g., innate lymphoid cells (ILCs), asthma forms are divided into those of a type-2 (mostly allergic) and those of a non-type-2 character, respectively. However, even this paradigm may not cover all possible mechanisms underlying different forms of asthma [8][9][13][15][16].

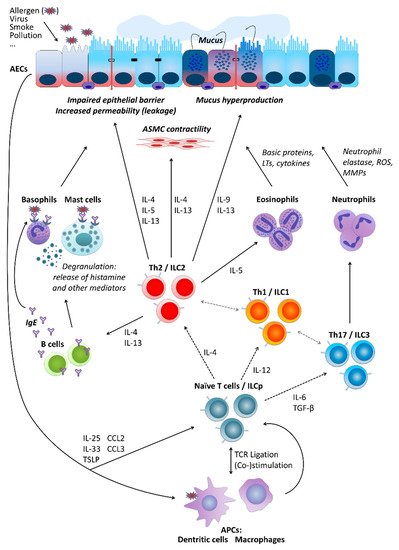

Partly independently of the pathomechanism behind it, several types of cells are crucially involved in asthma pathogenesis. These include airway epithelial cells (AECs) forming together with local macrophages the first point of contact for external influences entering the airways, for instance, allergens (type-2/atopic forms of asthma) or cigarette smoke (neutrophilic asthma belonging to non-type-2 disease forms). Cytokines secreted by AECs (e.g., thymic stromal lymphopoietin, TSLP; interleukin-25, IL-25; and IL-33) in response to stimulation influence of downstream cells including, among others, antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and T cells. Depending on the type of stimulation, T cells differentiate towards Th2 cells secreting cytokines driving allergic forms of the disease or Th17 and Th1 cells contributing to non-type-2 asthma endotypes. As type-2 cytokines, IL-4 triggers the differentiation of further Th2 cells and the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE) by B cells, IL-13 activates mast cells and basophils as well as stimulates airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell contractility and thus airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) and hyperplasia of goblet cells and mucus production, IL-5 activates eosinophils, IL-9 further contributes to increased mucus production and enhanced proliferation of mast cells. Mediators secreted by mast cells and basophils result in allergic inflammation of the respiratory tract accompanied by a respective clinical picture. IL-17 released by Th17 cells, in turn, stimulates neutrophil activation, which leads to severe endothelial injury typical for non-type-2 neutrophilic asthma (Figure 1) [9][14][17][18][19].

Basic cellular mechanisms underlying type-2 and non-type-2 asthma. For a more detailed description, please refer to the main text, Section 2. “Asthma”. AECs, airway epithelial cells; ASMC, airway smooth muscle cells; LTs, leukotrienes; ROS, reactive oxygen species; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; IL, interleukin; ILC, innate lymphoid cells; ILCp, ILC precursors; Th (cells), T helper (cells); IgE, immunoglobulin E; TGF-β, transforming growth factor beta; TSLP, thymic stromal lymphopoietin; CCL, C-C motif chemokine ligand; TCR, T cell receptor; APCs, antigen-presenting cells.

2.2. Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs)

2.3. Granulocytes and Mast Cells

2.4. Platelets

3. ConExtraclusions and Perspectivellular Vesicles

A key feature that has significantly contributed to the evolution of multicellular organisms and especially higher levels of complexity is represented by the ability of intercellular communication such as transfer of soluble molecules between cells and/or direct cell-cell contact. After the discovery that cells release so-called apoptotic bodies during programmed cell death, it was shown already in the mid-60s that physiologically active cells also release extracellular particles, at that time referred to as the so-called “platelet dust” [20]. However, within the last two decades, EVs have turned out to be more prominent and functionally important than initially expected and emerged as an interesting and promising research field. Virtually all cell types analyzed so far release EVs, which can roughly be classified into two major groups: endosomal derived exosomes and microvesicles (MVs; also referred to as microparticles or ectosomes), the latter directly budding from the plasma membrane [21][22][23][24][25]. Although exosomes and MVs show differences, such as their biogenesis and release pathways, they also share many bio-physicochemical properties, including size range, density as well as certain surface proteins (for a summary of the differential characteristics of EVs see Table 1) [26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33]. These features barely allow distinguishing between the individual subpopulations in detail. Instead of referring to the individual subpopulations, the term EV should therefore be preferred in the nomenclature, which encompasses vesicles released by cells in their entirety [34], however, in the current review we will retain the terminology used in the original publications to which we refer.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of extracellular vesicles of different types [26][27][31][32][33].

| Exosomes | Microvesicles | Apoptotic Bodies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alternative nomenclature | - | Microparticles, ectosomes | - |

| Size | 10–150 nm | 100–1000 nm | 800–5000 nm |

| Origin | Intraluminal vesicles within multivesicular bodies | Plasma membrane and cellular content | Plasma membrane, fragmented cell |

| Formation mechanism | Fusion of multivesicular bodies with plasma membrane | Outward blebbing of plasma membrane | Shrinkage and programmed death of the cell |

| Release | Constitutive and/or cell activation | Constitutive and/or cell activation | Apoptosis |

| Time of release | ≥10 min | <1 s | - |

| Composition | Protein, lipids, coding RNA, noncoding RNA, DNA | Protein, lipids, cell organelles, coding RNA, noncoding RNA, DNA | Cell organelles, proteins, nuclear fractions, coding RNA, noncoding RNA, DNA |

| Enriched protein markers | CD81, CD63, Alix, Tsg101 | Selectins, integrin, CD40 | Caspase 3, histones |

Since EVs play an important role in cell-cell communication, they are not simply empty lipid bins but rather contain various biomolecules such as diverse RNA types, proteins, lipids and metabolites by which they have the potential to regulate the function of recipient cells. With respect to EV-mediated signaling, non-coding RNAs were studied in depth during the last decade. In particular, the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) turned into the focus of research, due to their well-established role in the regulation of gene expression [35][36][37]. Interestingly, the way in which EVs avoid degradation while entering the cell compartment by endocytosis and subsequent cargo release via membrane fusion suggests that EVs exploit mechanisms similar to those observed in certain viral infections, such as endosomal acidification [38][39].

In line with this, recent studies also implicated EVs in the progression of human disease, including cancer and infectious diseases (for a summary see [40][41]).

References

- WHO. The Top 10 Causes of Death. Available online: (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- WHO. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard: With Vaccination Data. Available online: (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- Camps, J.; García-Heredia, A. Introduction: Oxidation and inflammation, a molecular link between non-communicable diseases. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2014, 824, 1–4.

- Pahwa, R.; Goyal, A.; Bansal, P.; Jialal, I. Chronic Inflammation; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021.

- Phillips, C.M.; Chen, L.-W.; Heude, B.; Bernard, J.Y.; Harvey, N.C.; Duijts, L.; Mensink-Bout, S.M.; Polanska, K.; Mancano, G.; Suderman, M.; et al. Dietary Inflammatory Index and Non-Communicable Disease Risk: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1873.

- Prynn, J.E.; Kuper, H. Perspectives on Disability and Non-Communicable Diseases in Low- and Middle-Income Countries, with a Focus on Stroke and Dementia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 3488.

- Ray, A.; Oriss, T.B.; Wenzel, S.E. Emerging molecular phenotypes of asthma. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2015, 308, L130–L140.

- Miethe, S.; Guarino, M.; Alhamdan, F.; Simon, H.-U.; Renz, H.; Dufour, J.-F.; Potaczek, D.P.; Garn, H. Effects of obesity on asthma: Immunometabolic links. Pol. Arch. Intern. Med. 2018, 128, 469–477.

- Potaczek, D.P.; Miethe, S.; Schindler, V.; Alhamdan, F.; Garn, H. Role of airway epithelial cells in the development of different asthma phenotypes. Cell. Signal. 2020, 69, 109523.

- Tost, J. A translational perspective on epigenetics in allergic diseases. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2018, 142, 715–726.

- Quirt, J.; Hildebrand, K.J.; Mazza, J.; Noya, F.; Kim, H. Asthma. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2018, 14, 50.

- Bush, A. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of Asthma. Front. Pediatr. 2019, 7, 68.

- Wenzel, S.E. Asthma phenotypes: The evolution from clinical to molecular approaches. Nat. Med. 2012, 18, 716–725.

- Alashkar Alhamwe, B.; Miethe, S.; Pogge von Strandmann, E.; Potaczek, D.P.; Garn, H. Epigenetic Regulation of Airway Epithelium Immune Functions in Asthma. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1747.

- Kuruvilla, M.E.; Lee, F.E.-H.; Lee, G.B. Understanding Asthma Phenotypes, Endotypes, and Mechanisms of Disease. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 2019, 56, 219–233.

- Carr, T.F.; Zeki, A.A.; Kraft, M. Eosinophilic and Noneosinophilic Asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2018, 197, 22–37.

- Potaczek, D.P.; Harb, H.; Michel, S.; Alhamwe, B.A.; Renz, H.; Tost, J. Epigenetics and allergy: From basic mechanisms to clinical applications. Epigenomics 2017, 9, 539–571.

- Gandhi, N.A.; Bennett, B.L.; Graham, N.M.H.; Pirozzi, G.; Stahl, N.; Yancopoulos, G.D. Targeting key proximal drivers of type 2 inflammation in disease. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2016, 15, 35–50.

- Jeong, J.S.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, Y.C. Defining Bronchial Asthma with Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase Delta Activation: Towards Endotype-Driven Management. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3525.

- Wolf, P. The nature and significance of platelet products in human plasma. Br. J. Haematol. 1967, 13, 269–288.

- Doyle, L.M.; Wang, M.Z. Overview of Extracellular Vesicles, Their Origin, Composition, Purpose, and Methods for Exosome Isolation and Analysis. Cells 2019, 8, 727.

- Akers, J.C.; Gonda, D.; Kim, R.; Carter, B.S.; Chen, C.C. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): Exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies. J. Neurooncol. 2013, 113, 1–11.

- Kowal, J.; Tkach, M.; Théry, C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2014, 29, 116–125.

- Raposo, G.; Stoorvogel, W. Extracellular vesicles: Exosomes, microvesicles, and friends. J. Cell Biol. 2013, 200, 373–383.

- van Niel, G.; D’Angelo, G.; Raposo, G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2018, 19, 213–228.

- Benedikter, B.J.; Wouters, E.F.M.; Savelkoul, P.H.M.; Rohde, G.G.U.; Stassen, F.R.M. Extracellular vesicles released in response to respiratory exposures: Implications for chronic disease. J. Toxicol. Environ. Health B Crit. Rev. 2018, 21, 142–160.

- Burger, D.; Schock, S.; Thompson, C.S.; Montezano, A.C.; Hakim, A.M.; Touyz, R.M. Microparticles: Biomarkers and beyond. Clin. Sci. 2013, 124, 423–441.

- Jan, A.T.; Rahman, S.; Khan, S.; Tasduq, S.A.; Choi, I. Biology, Pathophysiological Role, and Clinical Implications of Exosomes: A Critical Appraisal. Cells 2019, 8, 99.

- Lawson, C.; Vicencio, J.M.; Yellon, D.M.; Davidson, S.M. Microvesicles and exosomes: New players in metabolic and cardiovascular disease. J. Endocrinol. 2016, 228, R57–R71.

- Stahl, P.D.; Raposo, G. Extracellular Vesicles: Exosomes and Microvesicles, Integrators of Homeostasis. Physiology 2019, 34, 169–177.

- Ståhl, A.-L.; Johansson, K.; Mossberg, M.; Kahn, R.; Karpman, D. Exosomes and microvesicles in normal physiology, pathophysiology, and renal diseases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 34, 11–30.

- Todorova, D.; Simoncini, S.; Lacroix, R.; Sabatier, F.; Dignat-George, F. Extracellular Vesicles in Angiogenesis. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 1658–1673.

- Zhang, W.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, H.; Yao, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Z. Extracellular vesicles in diagnosis and therapy of kidney diseases. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2016, 311, F844–F851.

- Witwer, K.W.; Théry, C. Extracellular vesicles or exosomes? On primacy, precision, and popularity influencing a choice of nomenclature. J. Extracell. Vesicles 2019, 8, 1648167.

- Bélanger, É.; Madore, A.-M.; Boucher-Lafleur, A.-M.; Simon, M.-M.; Kwan, T.; Pastinen, T.; Laprise, C. Eosinophil microRNAs Play a Regulatory Role in Allergic Diseases Included in the Atopic March. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 9011.

- Pegtel, D.M.; Cosmopoulos, K.; Thorley-Lawson, D.A.; van Eijndhoven, M.A.J.; Hopmans, E.S.; Lindenberg, J.L.; de Gruijl, T.D.; Würdinger, T.; Middeldorp, J.M. Functional delivery of viral miRNAs via exosomes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 6328–6333.

- Valadi, H.; Ekström, K.; Bossios, A.; Sjöstrand, M.; Lee, J.J.; Lötvall, J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2007, 9, 654–659.

- Joshi, B.S.; de Beer, M.A.; Giepmans, B.N.G.; Zuhorn, I.S. Endocytosis of Extracellular Vesicles and Release of Their Cargo from Endosomes. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 4444–4455.

- O’Brien, K.; Breyne, K.; Ughetto, S.; Laurent, L.C.; Breakefield, X.O. RNA delivery by extracellular vesicles in mammalian cells and its applications. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2020, 21, 585–606.

- Becker, A.; Thakur, B.K.; Weiss, J.M.; Kim, H.S.; Peinado, H.; Lyden, D. Extracellular Vesicles in Cancer: Cell-to-Cell Mediators of Metastasis. Cancer Cell 2016, 30, 836–848.

- Coakley, G.; Maizels, R.M.; Buck, A.H. Exosomes and Other Extracellular Vesicles: The New Communicators in Parasite Infections. Trends Parasitol. 2015, 31, 477–489.