Dysregulation of the proteolytic balance is often associated with diseases. Serine proteases and matrix metalloproteases are involved in a multitude of biological processes and notably in the inflammatory response. Within the framework of digestive inflammation, several studies have stressed the role of serine proteases and matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) as key actors in its pathogenesis and pointed to the unbalance between these proteases and their respective inhibitors.

- gut microbiota

- protease

- serpin

- digestive inflammation

- holobiont

1. Introduction

The incidence of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) is rising in the Western world, affecting millions of patients in the US and Europe. Over the past decades, developing countries in Asia, South America and the Middle East reported the emergence of IBD, thus highlighting its evolution as a global disease [1]. Modern treatments are significantly improving the quality of life of patients; however, despite advances in the therapeutic field, treatment failure is common [2]. The etiology of IBD remains incompletely comprehended and seems to result from the interaction of genetic and environmental factors [3]. In the area of host–microbe interactions in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, environmental factors can modify the diversity and composition of the intestinal microbiota, which, for genetically predisposed individuals, attends a deterioration of the epithelial barrier integrity and triggers abnormal immune response [4].

The intestinal mucosa not only acts as a physical barrier preventing the entry of microorganisms or harmful components from the lumen into the blood circulation but also allows dietary nutrients’ absorption. Moreover, the GI tract hosts hundreds of trillions of microbes and is exposed to high levels of proteases. An important part of the literature has raised the key role of proteases in maintaining GI homeostasis, and their upregulation causes tissue damage and inflammation [5,6][5][6]. Recent studies have established the association between increased serine protease activity and IBD pathogenesis [7,8][7][8]. Due to their implication in tissue remodeling through their ability to degrade extracellular matrix (ECM) components and their immunomodulating effects [9], matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are considered key actors of IBD pathogenesis and its related complications such as fistula and fibrosis [10]. Under healthy conditions, the proteolytic activity of serine proteases and MMPs is tightly controlled by their respective protease inhibitors due to their implication in many biological processes. Dysregulation of this balance contributes to IBD pathophysiology [5,11][5][11].

2. Association between Proteolytic Enzymes and Digestive Inflammation

Serine proteases and metalloproteinases constitute two protease subfamilies, showing distinct structural features. In the case of metalloproteinases during peptide cleavage, the nucleophile attack is mediated by a water molecule in the presence of a Zn2+ divalent ion. However, the serine proteases form a covalent complex between the peptide and the catalytic serine residue upon the nucleophilic attack. Several reports have stressed the key role of these proteases in digestive inflammation.

2.1. Metalloproteases

MMPs are endoproteases containing a conserved zinc-binding motif in their catalytic site. This enzyme family shares a common domain organization consisting of a propeptide, a catalytic domain, a hinge region (linker) and a hemopexin domain. They can degrade components of the ECM, mediating its homeostasis. The cellular source of MMPs encompasses a wide range of cell types, including epithelial cells, macrophages, leukocytes, neutrophils and myofibroblasts. Investigation studies on MMP substrates’ specificity have unveiled the diversity of molecules cleaved by MMPs, including chemokines, cytokines, growth factors and receptors, thus shedding light on the involvement of MMPs in other biological processes such as angiogenesis, immunity and inflammatory response. Consistent with their role as key regulators, MMP activity is tightly regulated at several levels, from gene expression, activation to inhibition by specific inhibitors. MMPs inhibition will be discussed more specifically in a dedicated section of the present review.

Dysregulation in MMP expression and activity has been associated with several pathologic processes such as cancers, cardiovascular diseases, musculoskeletal disorders and chronic inflammation. In the context of IBD, many MMPs are found to be upregulated; for instance, MMP-1, -2, -3, -7, -8, -9, -10, -12 and -13. In patients with ulcerative colitis (UC), a correlation between MMP-1 expression in colonic mucosa and severity of clinical symptoms has been established [12]. In line with previous studies that have identified MMP-2 overexpression in the colonic mucosa of UC patients, Jakubowska et al. [13] demonstrated weak MMP-2 expression in infiltrative inflammatory cells and strong expression in the glandular epithelium of UC and Crohn’s disease (CD) patients. Matsuno et al. [14] established that the level of matrilysin (MMP-7) expression in epithelial cells at the edge of the ulcer of UC patients ties in with the disease activity. Conversely, stromelysin-1 (MMP-3) expression levels in epithelial and stromal cells were not different between patients with mild and those with severe inflammation. Immunostaining of mucosal samples from IBD patients revealed the enhanced expression of MMP-13, another member of the collagenase group of MMPs, which has been positively linked to histological inflammation scores [15]. Indeed, MMP-13 modulates intestinal permeability through the shedding of the transmembrane-bound tumor necrosis factor (TNF), thus releasing active soluble TNF [16]. This release has two effects: (i) it induces caveolin-dependent endocytosis, which results in tight junction (TJ) destabilization, and (ii) it stimulates the expression and secretion of mucin by goblet cells, which eventually cause endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, resulting in mucus depletion and leading to increased interactions between bacteria and intestinal epithelial and Paneth cells. Additionally, moderate protection to dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis was observed in MMP13−/− mice compared to MMP13+/+ mice [16]. In past years, many studies have focused on gelatinase B (MMP-9) as a novel therapeutic target for IBD treatment as a result of the association between its expression and disease development [17,18][17][18]. Al-Sadi et al. [19] demonstrated that MMP-9 causes an increase in intestinal tight-junction permeability via the p38 kinase signaling pathway, upregulating myosin light-chain kinase (MLCK) gene expression. Recent work [20] suggests that MMP-9 upregulation is a consequence of intestinal inflammation, which is in contradiction with a previous investigation that suggests its causative implication in an experimental model of colitis [21]. Collagen degradation by MMPs is an important factor in neutrophilic inflammation in IBD [22]. Neutrophil recruitment to sites of infection is usually mediated by the CXCL8 chemokine. Yet, proline-glycine-proline (PGP) peptide resulting from collagen degradation is also a neutrophil chemoattractant. Three enzymes are involved in its production: MMP-8, MMP-9 and prolyl endopeptidase (PE). Intestinal tissues from IBD patients have increased levels of MMP-8, MMP-9, PGP and its acetylated version (N-Ac-PGP), and PE levels show no difference compared to control. In mice with dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis, PGP neutralization results in a significant reduction of the disease activity index (DAI) score and infiltrating neutrophils, emphasizing its pathophysiological role in neutrophilic inflammation. Considering that (i) in vitro PGP induces the release of MMP-9 and CXCL8 from neutrophils and (ii) neutrophils from IBD patients secrete more MMP-8 and MMP-9 under unstimulated conditions and have increased migration capabilities toward CXCL8 than neutrophils from healthy patients, they form elements of a vicious circle of sustained neutrophilic inflammation in IBD. Recently, the contribution of MMP-10 and, to some extent, MMP-9 and -7 to CD, has been highlighted through the identification of their action on programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), an immune regulatory molecule present in myofibroblasts (MFs) [23]. In healthy conditions, MFs can suppress T-helper 1 (Th1)- and T-helper 17 (Th17)-type responses through the presence of PD-L1 molecules at their surface. In CD conditions, increased MMP-10 expression is linked to reduced levels of membrane-bound PD-L1 (mPD-L1) and a rise of the soluble form of PD-L1, leading to an impairment of the suppressing ability of MF on Th1 and Th17 activities. Levels of mPD-L1 of CD-MF are reinstated upon MMP-10 inhibition as well as their subsequent suppressing abilities. Although a strong increase in mPD-L1 levels is observed when inhibiting MMP-7 and MMP-9, the MF-mediated T-helper suppression function is only partially restored. The protective effect of MMP-19 over colitis seems to originate from its capacity to control neutrophils and macrophage migration to wounded mucosa, possibly through the processing of the chemokine domain of fractalkine (CX3CL1) [24]. In a DDS-induced model of colitis, MMP-19−/− mice show increased susceptibility and exacerbation of colitis reflected by a reduced survival rate, severe tissue destruction, increased levels of colonic and a plasmatic level of proinflammatory modulators and failure to resolve inflammation. In addition, a delay in the infiltration of neutrophils into the colon and reduced migration of macrophages is observed.

Of note, the MMP field of action may be extended to the primary nonresponsiveness of IBD patients to anti-TNF treatments [25]. Indeed, Barberio et al. [26] established that MMP-3 serum levels of IBD patients treated with infliximab are higher in nonresponders compared to responders. This suggests that MMP-3 serum levels may represent an early predictive marker of response to infliximab. In line with these results, three anti-TNF agents (infliximab, adalimumab and etanercept) are degraded by MMP-3 and MMP-12 in vitro, notably by the removal of their Fc region. While infliximab and adalimumab maintained their ability to neutralize TNF after MMP treatment, etanercept lost its neutralization capability. Notwithstanding, loss of the Fc region may still have clinically relevant consequences in vivo as some immunologic properties such as antibody-dependent, cell-mediated cytotoxicity and complement activation require an Fc region. Further in vivo investigations are required to decipher the real impact of MMPs on the nonresponsiveness to anti-TNF treatment mechanisms in IBD patients.

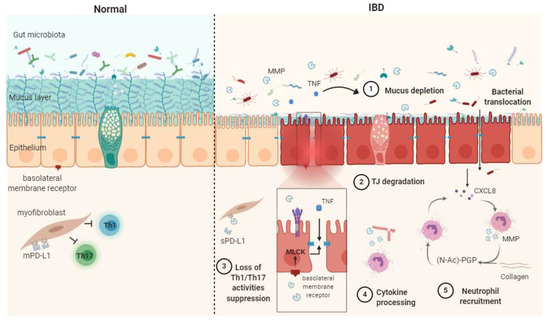

In summary, the dysregulation of MMPs can contribute to IBD via five main processes: cytokine processing, mucus depletion, tight-junction destabilization, neutrophil recruitment and stimulation and Th1/Th17 response (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of matrix metalloproteases (MMPs) mechanisms of action in healthy contet (Normal) and in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathophysiogenesis. The release of soluble TNF-α resulting from the shedding of membrane-bound TNF by MMPs causes mucus depletion (1) and tight-junction destabilization (2), leading to increased epithelial permeability and bacterial translocation. The abrogation of myofibroblast ability in suppressing Th1/Th17 occurs after the MMP processing of membrane-bound PD-L1 to produce soluble PD-L1 (3). Cytokine processing contributes to inflammation processes (4). PGP generation through collagen degradation by MMPs induces neutrophil transmigration and stimulates neutrophil MMP and CXCL8 secretion, therefore sustaining the inflammatory context (5). CXCL8: (C-X-C motif) ligand 8, MLCK: myosin light-chain kinase, PD-L1: programmed death-ligand 1, mPD-L1: membrane-bound PD-L1, sPD-L1: soluble PD-L1, (N-Ac)-PGP: (N-acetyl)-proline-glycine-proline, TJ: tight junction, TNF: tumor necrosis factor α.

2.2. Serine Proteases

The GI tract is regularly exposed to high levels of proteolytic enzymes from both host and enteric bacteria [27]. From the host side, these proteases can be released either by resident or infiltrating cells. Among infiltrating immune cells, neutrophils constitute a prime source of serine proteases. Their granules harbor significant amounts of elastase (HNE), proteinase 3 (PR3) and cathepsin G (catG), which are secreted upon inflammation [28]. Serine proteases can also originate from mast cells, which release tryptase, chymase, catG and granzyme B [29]. Indeed, increased serine protease activity has been detected in both tissue biopsies and fecal samples from IBD patients [7,8,11,30][7][8][11][30]. As major components of the neutrophil proteolytic repertoire, these proteases contribute to the inflammatory response by cleaving junctional proteins, activating protease-activated receptors (PARs) and processing cytokines and chemokines that are in charge of the recruitment and activation of immune cells to the site of inflammation [31]. Neutrophil elastase and catG, for instance, cleave the vascular endothelial cadherin occurring at cellular junctions and thus contribute to leukocyte transmigration to inflammatory sites [32,33][32][33]. Neutrophil proteases also participate in MMP regulation notably through the activation of pro-MMP2 by catG, PR3 and HNE [34] and the inactivation of TIMP-1 by the HNE [35]. Increased levels of HNE have been previously detected in plasma and the colonic mucosa from IBD patients and are therefore explored as a potential biomarker for IBD [36,37][36][37]. Such uncontrolled activity was shown to elicit detrimental effects and drive inflammation in a murine model [38]. CatG also activates PAR4 and elicits the disruption of the epithelial barrier integrity [39]. It is assumed that such effects were associated with MLCK activation, myosin light-chain (MLC) phosphorylation and subsequent TJ destabilization. CatG and PR3 also cleave chemokines such as CXCL5 and CXCL8, thus contributing to higher chemotactic activity toward neutrophils [40]. Other examples include thrombin, which showed a 100-fold increase in activity in colonic biopsies from IBD patients compared with healthy controls [7]. Such activity has been suggested to be derived from the intestinal epithelium and/or the recruitment and activation of prothrombin at the damaged sites following vascular lesions. Active thrombin has been shown to mediate claudin-5 disassembling and increase vascular permeability in vivo [41]. The same response was also induced by PAR1 agonists, suggesting a key role for PAR1 activation in the proinflammatory effects of thrombin. PAR1 is the prototype receptor of thrombin [42]. PAR4 can also be cleaved by thrombin, and quite recently, thrombin signaling through PAR2 activation has been uncovered [43]. Note that the inhibition of colonic thrombin by the intracolonic injection of dabigatran, a thrombin inhibitor, in 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulfonic acid (TNBS)-induced colitis in rats, resulted in a significant reduction of the inflammatory parameters. Mucosal mast cell chymase was also shown to evoke proinflammatory effects as it alters the distribution of tight-junction-associated proteins such as ZO-l and occludins and increases epithelial permeability [44]. The role of this enzyme is not limited to enhanced gut permeability and includes MMPs activation [45]. Indeed, chymase can convert pro-MMP-9 to its active form MMP-9 in vitro and therefore plays a role in extracellular matrix remodeling [45]. A recent study shows the implication of tryptase in promoting IBD-induced intestinal fibrosis by activating the PAR-2/Akt/mTOR pathway in fibroblasts [46]

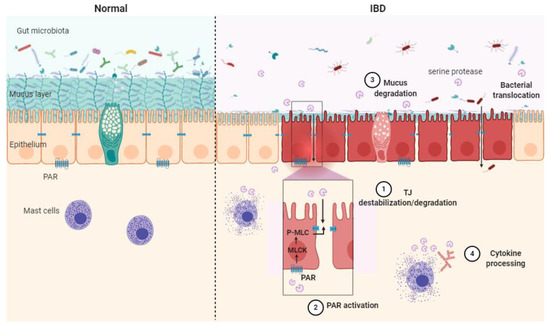

Serine protease contribution to IBD can be described through four main mechanisms: TJ destabilization/degradation, mucus degradation, PAR activation and cytokine processing (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic illustration of the serine protease mode of action in healthy context (Normal) and in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) pathology. Epithelial barrier impairment is associated with serine protease action on the tight junction through direct cleavage. (1) Indirect destabilization deriving from protease-activated receptor (PAR) activation (2), mucus degradation (3) and cytokine processing (4). MLC: myosin light-chain, P-MLC: phosphorylated MLC, MLCK: myosin light-chain kinase, PAR: protease-activated receptor, TJ: tight junction.

2.3. Role of Bacterial Proteases in Digestive Inflammation

The role of microbial proteases in the gut has been largely dismissed, partly due to limited tools setting apart host proteases from their microbial counterparts. Earlier studies have defined a significant contribution of bacterial proteases to proteolysis in the human large intestine [47]. Most identified proteases belong to Bacteroides, Streptococcus and Clostridium species [48]. Seeing that proteases are often studied as virulence factors, pathogen-derived proteases have mostly been explored for their effects in the GI tract. Such proteases have been described as key factors in (i) helping the bacterium to successfully compete with resident microbiota during infection and (ii) promoting bacterial fitness and survival under hostile conditions. Years ago, high-temperature serine protease A (HtrA) was defined as a key virulence factor of Listeria monocytogenes. L. monocytogenes is a facultative pathogen that has been shown to actively invade macrophages and epithelial cells as well as other neighboring host cells [49]. The lack of HtrA expression results in the impaired growth of such a bacterium under stressful conditions, including acidic pH or oxidative stress [50,51][50][51]. Additionally, an L. monocytogenes HtrA mutant revealed a reduced ability to form biofilms and was dimmed for virulence in mice [52]. Recently, a new presumed role of HtrA has been highlighted in listerial replication during infection, thus outlining the relevance of these chaperone serine proteases in bacterial infection [53]. The contribution of HtrA proteases to bacterial virulence has been explored in many other pathogens, including Campylobacter jejuni, Helicobacter pylori and Borrelia burgdorferi [54,55,56][54][55][56]. The main role of HtrA is related to protein quality control and the degradation of misfolded proteins to enhance bacterial fitness under hostile conditions. HtrA is also involved in the processing of tight junctional proteins, thereby leading to the disruption of epithelial barrier integrity [54,55,56][54][55][56]. Other bacteria, including intestinal adherent and invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), most likely secrete serine proteases to invade the mucous layer. A recently described protease produced by AIEC, known as VAT-AIEC, has been shown to contribute to gut colonization in a murine model by enhancing the expansion of bacteria through the mucous layer and adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells [57]. Besides enteric pathogens, nonvirulent bacteria also produce an extremely diverse repertoire of proteolytic enzymes that might contribute to gut inflammation. Subtilisin, a serine protease produced by the nonpathogenic Bacillus subtilis, has been shown to elicit plasma clotting and venous thromboembolism by proteolytically converting prothrombin (ProT) into active prethrombin-2 (σPre2) [58]. Venous thromboembolism is a known complication in patients with inflammatory disorders such as IBD that has been associated with significant morbidity and mortality [59,60][59][60].

The production of MMP by intestinal bacteria has been described as well. Strains of Bacteroides fragilis, for instance, produce a MMP that is able to cleave the ECM component E-cadherin [61], and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron encodes putative proteases with similar homology [62]. E-cadherin plays critical roles in maintaining the integrity of the epithelium barrier, and the loss or reduction of this protein expression has been linked to gastrointestinal disorders [63,64][63][64]. Clostridium perfringens MMP can target components of the ECM such as gelatin, type IV collagen and mucin and effectively degrade the mucus barrier [65]. More recently, the commensal bacterium Enterococcus faecalis was shown to produce gelatinase that cleaves E-cadherin, promoting colonic barrier impairment, thus increasing colitis severity in mice [66]. As proteases exhibit broad and pleiotropic effects, one could hypothesize that their microbial counterparts may have similar effects and could influence inflammation, wound healing, mucus cleavage, matrix remodeling, etc. As such, microbial proteolytic balance could be considered a promising contributor to gut homeostasis.

References

- Kaplan, G.G. The global burden of IBD: From 2015 to 2025. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2015, 12, 720–727.

- Volk, N.; Siegel, C.A. Defining Failure of Medical Therapy for Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2019, 25, 74–77.

- Zhang, M.; Sun, K.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Tso, P.; Wu, Z. Interactions between Intestinal Microbiota and Host Immune Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Front. Immunol. 2017, 8, 942.

- Neurath, M.F. Targeting immune cell circuits and trafficking in inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Immunol. 2019, 20, 970–979.

- Vergnolle, N. Protease inhibition as new therapeutic strategy for GI diseases. Gut 2016, 65, 1215–1224.

- Sina, C.; Lipinski, S.; Gavrilova, O.; Aden, K.; Rehman, A.; Till, A.; Rittger, A.; Podschun, R.; Meyer-Hoffert, U.; Haesler, R.; et al. Extracellular cathepsin K exerts antimicrobial activity and is protective against chronic intestinal inflammation in mice. Gut 2013, 62, 520–530.

- Denadai-Souza, A.; Bonnart, C.; Tapias, N.S.; Marcellin, M.; Gilmore, B.; Alric, L.; Bonnet, D.; Burlet-Schiltz, O.; Hollenberg, M.D.; Vergnolle, N.; et al. Functional Proteomic Profiling of Secreted Serine Proteases in Health and Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1–9.

- Jablaoui, A.; Kriaa, A.; Mkaouar, H.; Akermi, N.; Soussou, S.; Wysocka, M.; Wołoszyn, D.; Amouri, A.; Gargouri, A.; Maguin, E.; et al. Fecal Serine Protease Profiling in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10, 21.

- Ra, H.J.; Parks, W.C. Control of matrix metalloproteinase catalytic activity. Matrix Biol. 2007, 26, 587–596.

- Fontani, F.; Domazetovic, V.; Marcucci, T.; Vincenzini, M.T.; Iantomasi, T. MMPs, ADAMs and Their Natural Inhibitors in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Involvement of Oxidative Stress. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. Treat. 2017, 3, 39.

- Motta, J.P.; Magne, L.; Descamps, D.; Rolland, C.; Squarzoni-Dale, C.; Rousset, P.; Martin, L.; Cenac, N.; Balloy, V.; Huerre, M.; et al. Modifying the protease, antiprotease pattern by elafin overexpression protects mice from colitis. Gastroenterology 2011, 140, 1272–1282.

- Wang, Y.D.; Mao, J.W. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and tumor necrosis factor-α in ulcerative colitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, 5926–5932.

- Jakubowska, K.; Pryczynicz, A.; Iwanowicz, P.; Niewiński, A.; Maciorkowska, E.; Hapanowicz, J.; Jagodzińska, D.; Kemona, A.; Guzińska-Ustymowicz, K. Expressions of matrix metalloproteinases (MMP-2, MMP-7, and MMP-9) and their inhibitors (TIMP-1, TIMP-2) in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2016, 2016, 1–7.

- Matsuno, K.; Adachi, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Goto, A.; Arimura, Y.; Endo, T.; Itoh, F.; Imai, K. The expression of matrix metalloproteinase matrilysin indicates the degree of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. J. Gastroenterol. 2003, 38, 348–354.

- Vizoso, F.J.; González, L.O.; Corte, M.D.; Corte, M.G.; Bongera, M.; Martínez, A.; Martín, A.; Andicoechea, A.; Gava, R.R. Collagenase-3 (MMP-13) expression by inflamed mucosa in inflammatory bowel disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 41, 1050–1055.

- Vandenbroucke, R.E.; Dejonckheere, E.; Van Hauwermeiren, F.; Lodens, S.; De Rycke, R.; Van Wonterghem, E.; Staes, A.; Gevaert, K.; López-Otin, C.; Libert, C. Matrix metalloproteinase 13 modulates intestinal epithelial barrier integrity in inflammatory diseases by activating TNF. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 1000–1016.

- O’Sullivan, S.; Wang, J.; Pigott, M.T.; Docherty, N.; Boyle, N.; Lis, S.K.; Gilmer, J.F.; Medina, C. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 by a barbiturate-nitrate hybrid ameliorates dextran sulphate sodium-induced colitis: Effect on inflammation-related genes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2017, 174, 512–524.

- Marshall, D.C.; Lyman, S.K.; McCauley, S.; Kovalenko, M.; Spangler, R.; Liu, C.; Lee, M.; O’Sullivan, C.; Barry-Hamilton, V.; Ghermazien, H.; et al. Selective Allosteric Inhibition of MMP9 Is Efficacious in Preclinical Models of Ulcerative Colitis and Colorectal Cancer. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127063.

- Al-Sadi, R.; Youssef, M.; Rawat, M.; Guo, S.; Dokladny, K.; Haque, M.; Watterson, M.D.; Ma, T.Y. MMP-9-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight permeability is mediated by p38 kinase signaling pathway activation of MLCK gene. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2019, 316, G278–G290.

- De Bruyn, M.; Breynaert, C.; Arijs, I.; De Hertogh, G.; Geboes, K.; Thijs, G.; Matteoli, G.; Hu, J.; Van Damme, J.; Arnold, B.; et al. Inhibition of gelatinase B/MMP-9 does not attenuate colitis in murine models of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1–15.

- Santana, A.; Medina, C.; Paz-Cabrera, M.C.; Díaz-Gonzalez, F.; Farré, E.; Salas, A.; Radomski, M.W.; Quintero, E. Attenuation of dextran sodium sulphate induced colitis in matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficient mice. World J. Gastroenterol. 2006, 12, 6464–6472.

- Koelink, P.J.; Overbeek, S.A.; Braber, S.; Morgan, M.E.; Henricks, P.A.; Abdul Roda, M.; Verspaget, H.W.; Wolfkamp, S.C.; Velde, A.A.T.; Jones, C.W.; et al. Collagen degradation and neutrophilic infiltration: A vicious circle in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2014, 63, 578–587.

- Aguirre, J.E.; Beswick, E.J.; Grim, C.; Uribe, G.; Tafoya, M.; Palma, G.C.; Samedi, V.; McKee, R.; Villeger, R.; Fofanov, Y.; et al. Matrix metalloproteinases cleave membrane-bound PD-L1 on CD90+ (myo-)fibroblasts in Crohn’s disease and regulate Th1/Th17 cell responses. Int. Immunol. 2020, 32, 57–68.

- Brauer, R.; Tureckova, J.; Kanchev, I.; Khoylou, M.; Skarda, J.; Prochazka, J.; Spoutil, F.; Beck, I.M.; Zbodakova, O.; Kasparek, P.; et al. MMP-19 deficiency causes aggravation of colitis due to defects in innate immune cell function. Mucosal Immunol. 2016, 9, 974–985.

- Biancheri, P.; Brezski, R.J.; Di Sabatino, A.; Greenplate, A.R.; Soring, K.L.; Corazza, G.R.; Kok, K.B.; Rovedatti, L.; Vossenkämper, A.; Ahmad, N.; et al. Proteolytic cleavage and loss of function of biologic agents that neutralize tumor necrosis factor in the mucosa of patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology 2015, 149, 1564–1574.e3.

- Barberio, B.; D’Incà, R.; Facchin, S.; Dalla Gasperina, M.; Tagne, C.A.F.; Cardin, R.; Ghisa, M.; Lorenzon, G.; Marinelli, C.; Savarino, E.V.; et al. Matrix Metalloproteinase 3 Predicts Therapeutic Response in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Patients Treated with Infliximab. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2020, 26, 756–763.

- Barrett, A.J.; Rawlings, N.D.; Woessner, J.F. Handbook of Proteolytic Enzymes; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003.

- Meyer-Hoffert, U.; Wiedow, O. Neutrophil serine proteases: Mediators of innate immune responses. Curr. Opin. Hematol. 2011, 18, 19–24.

- Dai, H.; Korthuis, R.J. Mast Cell Proteases and Inflammation. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Model. 2011, 8, 47–55.

- Rolland-Fourcade, C.; Denadai-Souza, A.; Cirillo, C.; Lopez, C.; Jaramillo, J.O.; Desormeaux, C.; Cenac, N.; Motta, J.P.; Larauche, M.; Taché, Y.; et al. Epithelial expression and function of trypsin-3 in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut 2017, 66, 1767–1778.

- Solà-Tapias, N.; Vergnolle, N.; Denadai-Souza, A.; Barreau, F. The Interplay between Genetic Risk Factors and Proteolytic Dysregulation in the Pathophysiology of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Crohns Colitis 2020, 14, 1149–1161.

- Cohen-Mazor, M.; Mazor, R.; Kristal, B.; Sela, S. Elastase and cathepsin G from primed leukocytes cleave vascular endothelial cadherin in hemodialysis patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–10.

- Hermant, B.; Bibert, S.; Concord, E.; Dublet, B.; Weidenhaupt, M.; Vernet, T.; Gulino-Debrac, D. Identification of proteases involved in the proteolysis of vascular endothelium cadherin during neutrophil transmigration. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 14002–14012.

- Shamamian, P.; Schwartz, J.D.; Pocock, B.J.; Monea, S.; Whiting, D.; Marcus, S.G.; Mignatti, P. Activation of progelatinase A (MMP-2) by neutrophil elastase, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3: A role for inflammatory cells in tumor invasion and angiogenesis. J. Cell Physiol. 2001, 189, 197–206.

- Itoh, Y.; Nagase, H. Preferential inactivation of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 that is bound to the precursor of matrix metalloproteinase 9 (progelatinase B) by human neutrophil elastase. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 16518–16521.

- Adeyemi, E.O.; Neumann, S.; Chadwick, V.S.; Hodgson, H.J.; Pepys, M.B. Circulating human leucocyte elastase in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 1985, 26, 1306–1311.

- Langhorst, J.; Boone, J.; Lauche, R.; Rueffer, A.; Dobos, G. Faecal Lactoferrin, Calprotectin, PMN-elastase, CRP, and White Blood Cell Count as Indicators for Mucosal Healing and Clinical Course of Disease in Patients with Mild to Moderate Ulcerative Colitis: Post Hoc Analysis of a Prospective Clinical Trial. J. Crohns Colitis 2016, 10, 786–794.

- Barry, R.; Ruano-Gallego, D.; Radhakrishnan, S.T.; Lovell, S.; Yu, L.; Kotik, O.; Glegola-Madejska, I.; Tate, E.W.; Choudhary, J.S.; Williams, H.R.T.; et al. Faecal neutrophil elastase-antiprotease balance reflects colitis severity. Mucosal. Immunol. 2020, 13, 322–333.

- Dabek, M.; Ferrier, L.; Annahazi, A.; Bézirard, V.; Polizzi, A.; Cartier, C.; Leveque, M.; Roka, R.; Wittmann, T.; Theodorou, V.; et al. Intracolonic infusion of fecal supernatants from ulcerative colitis patients triggers altered permeability and inflammation in mice: Role of cathepsin G and protease-activated receptor-4. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1409–1414.

- Mortier, A.; Loos, T.; Gouwy, M.; Ronsse, I.; Van Damme, J.; Proost, P. Posttranslational modification of the NH2-terminal region of CXCL5 by proteases or peptidylarginine Deiminases (PAD) differently affects its biological activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 29750–29759.

- Kondo, N.; Ogawa, M.; Wada, H.; Nishikawa, S. Thrombin induces rapid disassembly of claudin-5 from the tight junction of endothelial cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2009, 315, 2879–2887.

- Cirino, G.; Vergnolle, N. Proteinase-activated receptors (PARs): Crossroads between innate immunity and coagulation. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2006, 6, 428–434.

- Mihara, K.; Ramachandran, R.; Saifeddine, M.; Hansen, K.K.; Renaux, B.; Polley, D.; Gibson, S.; Vanderboor, C.; Hollenberg, M.D. Thrombin-Mediated Direct Activation of Proteinase-Activated Receptor-2: Another Target for Thrombin Signaling. Mol. Pharmacol. 2016, 89, 606–614.

- Scudamore, C.L.; Jepson, M.A.; Hirst, B.H.; Miller, H.R. The rat mucosal mast cell chymase, RMCP-II, alters epithelial cell monolayer permeability in association with altered distribution of the tight junction proteins ZO-1 and occludin. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 1998, 75, 321–330.

- Ishida, K.; Takai, S.; Murano, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Inoue, T.; Murano, N.; Inoue, N.; Jin, D.; Umegaki, E.; Higuchi, K.; et al. Role of chymase-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 activation in mice with dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2008, 324, 422–426.

- Liu, B.; Yang, M.Q.; Yu, T.Y.; Yin, Y.Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.D.; He, Z.G.; Yin, L.; Chen, C.Q.; Li, J.Y. Mast Cell Tryptase Promotes Inflammatory Bowel Disease—Induced Intestinal Fibrosis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2021, 27, 242–255.

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Allison, C.; Gibson, S.A.; Cummings, J.H. Contribution of the microflora to proteolysis in the human large intestine. J. Appl. Bacteriol. 1988, 64, 37–46.

- Macfarlane, G.T.; Cummings, J.H.; Allison, C. Protein degradation by human intestinal bacteria. Microbiology 1986, 132, 1647–1656.

- Pizarro-Cerdá, J.; Cossart, P. Listeria monocytogenes: Cell biology of invasion and intracellular growth. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6.

- Wonderling, L.D.; Wilkinson, B.J.; Bayles, D.O. The htrA (degP) gene of Listeria monocytogenes 10403S is essential for optimal growth under stress conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1935–1943.

- Stack, H.M.; Sleator, R.D.; Bowers, M.; Hill, C.; Gahan, C.G. Role for HtrA in stress induction and virulence potential in Listeria monocytogenes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 4241–4247.

- Wilson, R.L.; Brown, L.L.; Kirkwood-Watts, D.; Warren, T.K.; Lund, S.A.; King, D.S.; Jones, K.F.; Hruby, D.E. Listeria monocytogenes 10403S HtrA is necessary for resistance to cellular stress and virulence. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 765–768.

- Ahmed, J.K.; Freitag, N.E. Secretion Chaperones PrsA2 and HtrA Are Required for Listeria monocytogenes Replication following Intracellular Induction of Virulence Factor Secretion. Infect. Immun. 2016, 84, 3034–3046.

- Elmi, A.; Nasher, F.; Jagatia, H.; Gundogdu, O.; Bajaj-Elliott, M.; Wren, B.; Dorrell, N. Campylobacter jejuni outer membrane vesicle-associated proteolytic activity promotes bacterial invasion by mediating cleavage of intestinal epithelial cell E-cadherin and occludin. Cell. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 561–572.

- Hoy, B.; Löwer, M.; Weydig, C.; Carra, G.; Tegtmeyer, N.; Geppert, T.; Schröder, P.; Sewald, N.; Backert, S.; Schneider, G.; et al. Helicobacter pylori HtrA is a new secreted virulence factor that cleaves E-cadherin to disrupt intercellular adhesion. EMBO Rep. 2010, 11, 798–804.

- Coleman, J.L.; Toledo, A.; Benach, J.L. HtrA of Borrelia burgdorferi Leads to Decreased Swarm Motility and Decreased Production of Pyruvate. mBio 2018, 9.

- Gibold, L.; Garenaux, E.; Dalmasso, G.; Gallucci, C.; Cia, D.; Mottet-Auselo, B.; Faïs, T.; Darfeuille-Michaud, A.; Nguyen, H.T.; Barnich, N.; et al. The Vat-AIEC protease promotes crossing of the intestinal mucus layer by Crohn’s disease-associated Escherichia coli. Cell. Microbiol. 2016, 18, 617–631.

- Pontarollo, G.; Acquasaliente, L.; Peterle, D.; Frasson, R.; Artusi, I.; De Filippis, V. Non-canonical proteolytic activation of human prothrombin by subtilisin from Bacillus subtilis may shift the procoagulant-anticoagulant equilibrium toward thrombosis. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 15161–15179.

- Cheng, K.; Faye, A.S. Venous thromboembolism in inflammatory bowel disease. World J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 26, 1231–1241.

- Andrade, A.R.; Barros, L.L.; Azevedo, M.F.C.; Carlos, A.S.; Damião, A.O.M.C.; Sipahi, A.M.; Leite, A.Z.A. Risk of thrombosis and mortality in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2018, 9, 142.

- Wu, S.; Lim, K.C.; Huang, J.; Saidi, R.F.; Sears, C.L. Bacteroides fragilis enterotoxin cleaves the zonula adherens protein, E-cadherin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1998, 95, 14979–14984.

- Thornton, R.F.; Murphy, E.C.; Kagawa, T.F.; O’Toole, P.W.; Cooney, J.C. The effect of environmental conditions on expression of Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron C10 protease genes. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 190.

- Daulagala, A.C.; Bridges, M.C.; Kourtidis, A. E-cadherin Beyond Structure: A Signaling Hub in Colon Homeostasis and Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 2756.

- Schnoor, M. E-cadherin Is Important for the Maintenance of Intestinal Epithelial Homeostasis under Basal and Inflammatory Conditions. Dig. Dis. Sci. 2015, 60, 816–818.

- Pruteanu, M.; Hyland, N.P.; Clarke, D.J.; Kiely, B.; Shanahan, F. Degradation of the extracellular matrix components by bacterial-derived metalloproteases: Implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2011, 17, 1189–1200.

- Maharshak, N.; Huh, E.Y.; Paiboonrungruang, C.; Shanahan, M.; Thurlow, L.; Herzog, J.; Djukic, Z.; Orlando, R.; Pawlinski, R.; Ellermann, M.; et al. Enterococcus faecalis Gelatinase Mediates Intestinal Permeability via Protease-Activated Receptor 2. Infect. Immun. 2015, 83, 2762–2770.