Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is one of primary cancers that frequently metastasize to the brain.

- renal cell carcinoma

- brain metastasis

- prognostic factors

- cytoreductive nephrectomy

1. Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 3–5% of all solid malignancies diagnosed worldwide [1]. Approximately one-third of patients with RCC present with metastatic disease at diagnosis, and amongst those with a radically resected localized disease, around 30% will develop metachronous metastases, in up to 17% of cases localized to the brain [2][3].

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 3–5% of all solid malignancies diagnosed worldwide [1]. Approximately one-third of patients with RCC present with metastatic disease at diagnosis, and amongst those with a radically resected localized disease, around 30% will develop metachronous metastases, in up to 17% of cases localized to the brain [2,3].

Patients with sarcomatoid component, large tumor size and lymph node involvement have a higher risk of developing brain metastases (BM) [4]. Despite the improved outcome of metastatic RCC (mRCC) patients, mainly due to the availability novel systemic therapies, BM are associated with a worse prognosis with a median overall survival (mOS), hardly reaching 10 months [5][6][7]. Poor prognosis might be related to the typical resistance to radiotherapy of brain metastatic renal cell carcinoma (BMRCC), the poor penetration of blood-brain barrier (BBB) by many anti-cancer agents [8][9][10], and also by the frequent occurrence of symptomatic neurological impairment. Indeed, central nervous system (CNS) symptoms are observed in as much as 70–80% of the patients with BMRCC.

Patients with sarcomatoid component, large tumor size and lymph node involvement have a higher risk of developing brain metastases (BM) [4]. Despite the improved outcome of metastatic RCC (mRCC) patients, mainly due to the availability novel systemic therapies, BM are associated with a worse prognosis with a median overall survival (mOS), hardly reaching 10 months [5,6,7]. Poor prognosis might be related to the typical resistance to radiotherapy of brain metastatic renal cell carcinoma (BMRCC), the poor penetration of blood-brain barrier (BBB) by many anti-cancer agents [8,9,10], and also by the frequent occurrence of symptomatic neurological impairment. Indeed, central nervous system (CNS) symptoms are observed in as much as 70–80% of the patients with BMRCC.

Furthermore, BMRCC display a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage due to its hypervascular structure [11], often leading to the need for surgical intervention to manage neurological complications [5][12].

Furthermore, BMRCC display a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage due to its hypervascular structure [11], often leading to the need for surgical intervention to manage neurological complications [5,12].

To our knowledge, there are no officially accepted guidelines regarding CNS surveillance in RCC patients, neither in the non-metastatic, nor in metastatic, settings. Although, data are available regarding the improved outcome in well-selected patients due to early BM diagnosis [13][14].

To our knowledge, there are no officially accepted guidelines regarding CNS surveillance in RCC patients, neither in the non-metastatic, nor in metastatic, settings. Although, data are available regarding the improved outcome in well-selected patients due to early BM diagnosis [13,14].

In relation to BMRCC treatment, neuro-surgery or stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) alone, or in combination, represent the gold standard in single or oligo-metastasis. While, whole brain radiotherapy (WBRT) progressively lost its role, and thus, it is limited to the treatment of multiple metastases not amenable to focal therapy [15].

New treatment options, based on targeted agents and/or immunotherapy, have dramatically improved the outcome of metastatic RCC (mRCC) patients. On the other hand, no general consensus on the activity and efficacy of these treatment in BMRCC exist, due to the limited evidence available and the consequent lack of consensus among the scientific community [16].

2. Clinico-Radiological Features of BMRCC and Indications for Brain Surveillance in RCC Patients

BM occur in mRCC with an incidence ranging from 2% to 17% [3][17][18][19], which appears to have significantly increased in the last two decades as a consequence of the increasing life expectancy of mRCC patients due to the availability of effective systemic therapies [4].

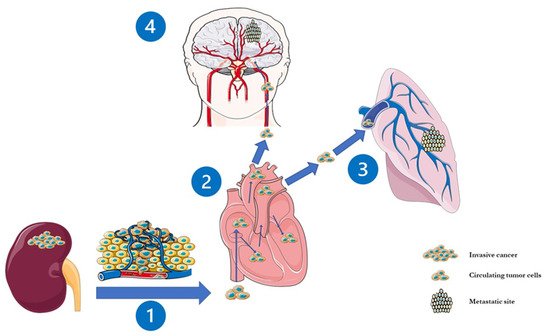

BM occur in mRCC with an incidence ranging from 2% to 17% [3,17,18,19], which appears to have significantly increased in the last two decades as a consequence of the increasing life expectancy of mRCC patients due to the availability of effective systemic therapies [4]. An estimated 2.4% of patients with non-metastatic RCC develops metachronous BM, while only 6.5% have BM already at the time of primary diagnosis [2]. Therefore, BMRCC more often occurs as a metachronous dissemination through different pathways, the most relevant being the cava-type pathway (75% of the cases,Figure 1). This justifies the common observation that BMRCC patients usually present also lung metastasis [2][20][21].

). This justifies the common observation that BMRCC patients usually present also lung metastasis [2,20,21].

Figure 1.

1

2

3

4

To date, several published studies found an increased risk of developing BMRCC in patients with clear cell histology, sarcomatoid differentiation, younger age (<70 years), larger tumour size (>7 cm or 10 cm) and lymphnode metastatic involvement [4][22][23].

To date, several published studies found an increased risk of developing BMRCC in patients with clear cell histology, sarcomatoid differentiation, younger age (<70 years), larger tumour size (>7 cm or 10 cm) and lymphnode metastatic involvement [4,22,23].In relation to the radiological features of BMRCC, these lesions are usually characterized by an increased vascularity, often associated with significant vasogenic peritumoral oedema, with a consequent higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Overall, this leads to localized and non-localized CNS symptoms, such as headache, confusion, altered mental status or behavior, sensor and/or motor deficits, as well as seizures [3][24][25][26][27].

In relation to the radiological features of BMRCC, these lesions are usually characterized by an increased vascularity, often associated with significant vasogenic peritumoral oedema, with a consequent higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage. Overall, this leads to localized and non-localized CNS symptoms, such as headache, confusion, altered mental status or behavior, sensor and/or motor deficits, as well as seizures [3,24,25,26,27]. If untreated, asymptomatic patients will usually become symptomatic with time [28]. At the time of our analysis, current guidelines for localized RCC do not recommend brain imaging evaluation unless patients present CNS symptoms [1], even if published guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend brain imaging surveillance in other tumors with brain tropism, such as lung cancer, breast cancer and melanoma, even in asymptomatic patients. This type of brain surveillance has led to improved OS, which was attributed to early detection and treatment [29].In relation to RCC, some retrospective studies have shown potentially survival benefits derived from CNS screening, with the aim of early identifying smaller lesions that are more amenable to less invasive treatments, potentially resulting in decreased morbidity. In this regard, the evidence of solitary and smaller BM in selected younger patients with a good performance status can lead to a prolonged survival from aggressive therapy, and decreased CNS recurrence risk. [5][30].

In relation to RCC, some retrospective studies have shown potentially survival benefits derived from CNS screening, with the aim of early identifying smaller lesions that are more amenable to less invasive treatments, potentially resulting in decreased morbidity. In this regard, the evidence of solitary and smaller BM in selected younger patients with a good performance status can lead to a prolonged survival from aggressive therapy, and decreased CNS recurrence risk. [5,30]. As a consequence, periodic CNS surveillance during the treatment of mRCC, without BM, may be worth doing, in order to identify patients who can benefit from earlier therapy aimed at survival improvement [31].3. BMRCC’s Prognostic Factors and Risk Scales

Several researchers looked at BMRCC clinico-molecular and radiological features with respect to their outcome, with the aim of identifying prognostic factors and developing risk scales to guide clinicians’ therapeutic choices. In this regard, in 2010, Sperduto et al. published a multi-institutional analysis of 4259 patients with BM from solid tumors. This led to the development of the Diagnosis-Specific Graded Prognostic Assessment (DS-GPA) tool, aimed at identifying significant diagnosis-specific prognostic factors and indexes. The hypothesis of their analysis was based on the concept that BM might behave differently depending on the primary tumor type, and as a consequence, should be treated differently based on their primitive site of disease. In this analysis, the authors found that significant prognostic factors varied with histological diagnosis and, focusing on RCC, identified as significant prognostic factors the Karnofsky performance status and the number of BMs (1 versus 2–3 versus >3) [32]. Further studies specifically focused on BMRCC. In particular, Bennani et al. retrospectively analyzed prognostic factors of 28 patients with BMRCC. mOS from BM onset was 13.3 months, one-year survival rate was 60.2% and two-year survival rate was 16.4%. Significant prognostic factors since BM’s diagnosis were the presence of intracranial hypertension (ICH), and/or other systemic metastasis, the absence of deep BMs metastasis and the surgical resection, the latter underlying the importance of defining surgical criteria for operability. In fact, patients who underwent surgery exhibited a markedly longer survival (25.7 months). Whereas, non-operated patients had a shorter survival (8.5 months). The surgical selection of patients has been influenced by the presence of a single brain metastasis, an accessible location within the brain, as well as a controlled systemic disease. The authors, in this analysis, did not confirm the prognostic role of DS-GPA criteria, evidencing a non-uniformity of accepted BMRCC prognostic factors [13]. Moreover, poor MSKCC risk score, the presence of sarcomatoid component and more than 3 BMs were indicated as prognostic factors of poorer outcome in a multivariate analysis of 93 BMRCC patients treated at University of Ulsan College of Medicine. On the other hand, local treatment was identified as an independent factor for a better OS. In this work, which was published in 2017, Choi SY et al. examined the survival differences between synchronous and metachronous BM, and did not find any differences, in terms of BM progression and OS after the diagnosis of BM [14]. Takeshita et al. confirmed, in their study, which was published in 2019, the prognostic factors evidenced in the above-mentioned papers, including DS-GPA. In particular, in their study, BMRCC features are associated with poor OS were KPS < 70, a DS-GPA score ≤ 2, no treatment for brain metastasis and the presence of sarcomatoid components. Moreover, OS plots showed a lower mOS for patients with a GPA ≤ 2 than those with a GPA > 2 as for patients with sarcomatoid components [33]. More recently, El Ali et al. retrospectively analysed a cohort of 93 BMRCC patients in order to validate, in mRCC, two prognostic scores formulated for BM from different tumor hystologies (namely the “Radiation Therapy Oncology Group Recursive Partitioning Analysis”—RTOG RPA and the “Basic Score for Brain Metastases”—BS-BM). Moreover, the same authors formulated a potential new prognostic score, named CERENAL score, which is specifically tailored on RCC. In this work, patients were distributed among RTOG RPA classes I, II or III basing on age, KPS and presence of extracranial metastases at brain metastasis diagnosis. On the other hand, the BS-BM was determined using KPS, management of systemic disease and presence of extracranial metastases at brain metastasis diagnosis. The new edited CERENAL prognostic score was based on the prognostic parameters used for the RTOG RPA and the BS-BM and on new findings that showed that a low number of intracranial metastases and SRS may predict a substantial survival benefit for metastatic RCC patients. In their analysis, all prognostic scores showed significance for PFS after first-line targeted therapy and a multivariate analysis proved that the CERENAL score was the sole independent prognostic factor associated with an improved PFS from first-line therapy. In relation to OS, the authors confirmed, in a univariate analysis the prognostic value of the three prognostic scores [34]. The principal characteristics of BMRCC prognostic score are summed in .Table 1.

| DS-GPA * |

|---|

| Points | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| KPS | <70 | 70–80 | 90–100 |

| No of BMs | >3 | 2–3 | 1 |

| RTOG RPA | |||

| Class | I | II | III |

| KPS | ≥70 | ≥70 | <70 |

| and | and | and | |

| Age | <65 | all | all |

| and | and | and | |

| Extracranial metastases | No | No/Yes | No/Yes |

| BS-BM * | |||

| Points | 0 | 1 | |

| KPS | ≤70 | ≥80 | |

| Systemic disease | PD | SD-PR-CR-NED | |

| Extracranial metastases | Yes | No | |

| CERENAL * | |||

| Points | 0 | 1 | |

| KPS | >70 | ≤70 | |

| Age | ≤50 | >50 | |

| PD of systemic disease | No | Yes | |

| Extracranial metastases | No | Yes | |

| No of BM | 1 | ≥2 | |

| SRS | Yes | No |

*

4. Role of Cytoreductive Nephrectomy

Beyond the debate which surrounds cytoreductive nephrectomy (cyNx) in the post-CARMENA era, Fclinicinal score is obtainans usually do not suggest cyNx in patients with BMRCC, due to their poor prognosis (mOS 11 months), especially when lesions are synchronous. Although no prospective data are available in this setting, to date, BMRCCs are considered a de facto contraindication to cyNx.

Dedspite all the by sum of all individual points; GPA of 4.0 indicates best prognosis and 0.0 indicates worst; for BS-BM and above, Daugherty M. et al. retrospectively collected clinico-therapeutic information and outcomes of 775 synchronous BM from RCC, focusing on the putative prognostic role of cyNx. In their cohort, the authors evidenced that patients with brain-only metastasis were more likely to undergo cyNx with respect to the counterpart with extracranial metastasis (40.8% vs. 20.8%). More importantly, patients with isolated BM who underwent cyNx displayed similar survival rates than those with isolated lung, liver, or bone metastasis, thus, showing that the presence of isolated BM did not correlate with a worse prognosis, as compared to another isolated extracranial metastasis. Similarly, in patients who did not undergo cyNx, no significant differences, in terms of outcome based on the site of isolated metastases (brain only versus lung only, brain only versus liver only, and brain only versus bone only) were observed. Furthermore, the subgroup with isolated BMRCC showed a better outcome if compared to those with multiple sites of disease with a 1 and 2 year survival of 44%, and 31%, respectively, for the brain-only subgroup. Notably, patients who underwent cyNx in the setting of brain-only metastasis had a significantly improved one- and two-year survival of 67%, and 52%, respectively, and an overall median survival of 33 months. Interestingly, patients with isolated BMRCC, who were not treated with cyNx, had a one- and two-year survival rates of 26% and 14%, and a median survival of five months. From these results, the detection of BMRCC should not necessarily be considered an indication of poor prognosis; what seems more important is the presence of an oligometastatic disease, and in particular, one metastatic site only, irrespective of the anatomic localization [35].

Zhuang et al. examined 933 RCC patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 with BM within the Surveillance, ERENAL, cut-off of worse prognpidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. The authors found that cyNx provided significant benefits in terms of survival. Indeed, survival analysis performed on matched cases showed that mOS of nephrectomized patients was 14.0 months, versus 5.0 months for the non-surgical group, a difference which was statistically significant. To date, it has been taken in count that cyNx has a 30-day mortality of 0.5–1.8% and that the perioperative mortality is associated with increasing tumour stage and depends also on surgeon and hospital operative volume. Moreover, severe complications occur in 3–8% of patients undergoing cyNx [22].

As a whole, prosis was taken at ≤2 and ≤4, repective clinical trials would be needed to clarify the prognostic role of cyNx in synchronous BMRCC. Furthermore, the positive combination of good KPS, low cerebral burden of disease, surgical resectability and the absence of other metastatic sites, as predictors of benefit from cyNx, should be prospectively confirmed.

4. Role of Cytoreductive Nephrectomy

Beyond the debate which surrounds cytoreductive nephrectomy (cyNx) in the post-CARMENA era, clinicians usually do not suggest cyNx in patients with BMRCC, due to their poor prognosis (mOS 11 months), especially when lesions are synchronous. Although no prospective data are available in this setting, to date, BMRCCs are considered a de facto contraindication to cyNx.

Despite all the above, Daugherty M. et al. retrospectively collected clinico-therapeutic information and outcomes of 775 synchronous BM from RCC, focusing on the putative prognostic role of cyNx. In their cohort, the authors evidenced that patients with brain-only metastasis were more likely to undergo cyNx with respect to the counterpart with extracranial metastasis (40.8% vs. 20.8%). More importantly, patients with isolated BM who underwent cyNx displayed similar survival rates than those with isolated lung, liver, or bone metastasis, thus, showing that the presence of isolated BM did not correlate with a worse prognosis, as compared to another isolated extracranial metastasis. Similarly, in patients who did not undergo cyNx, no significant differences, in terms of outcome based on the site of isolated metastases (brain only versus lung only, brain only versus liver only, and brain only versus bone only) were observed. Furthermore, the subgroup with isolated BMRCC showed a better outcome if compared to those with multiple sites of disease with a 1 and 2 year survival of 44%, and 31%, respectively, for the brain-only subgroup. Notably, patients who underwent cyNx in the setting of brain-only metastasis had a significantly improved one- and two-year survival of 67%, and 52%, respectively, and an overall median survival of 33 months. Interestingly, patients with isolated BMRCC, who were not treated with cyNx, had a one- and two-year survival rates of 26% and 14%, and a median survival of five months. From these results, the detection of BMRCC should not necessarily be considered an indication of poor prognosis; what seems more important is the presence of an oligometastatic disease, and in particular, one metastatic site only, irrespective of the anatomic localization [35].

Zhuang et al. examined 933 RCC patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2014 with BM within the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database. The authors found that cyNx provided significant benefits in terms of survival. Indeed, survival analysis performed on matched cases showed that mOS of nephrectomized patients was 14.0 months, versus 5.0 months for the non-surgical group, a difference which was statistically significant. To date, it has been taken in count that cyNx has a 30-day mortality of 0.5–1.8% and that the perioperative mortality is associated with increasing tumour stage and depends also on surgeon and hospital operative volume. Moreover, severe complications occur in 3–8% of patients undergoing cyNx [22].

As a whole, prospective clinical trials would be needed to clarify the prognostic role of cyNx in synchronous BMRCC. Furthermore, the positive combination of good KPS, low cerebral burden of disease, surgical resectability and the absence of other metastatic sites, as predictors of benefit from cyNx, should be prospectively confirmed.