Transthyretin (TTR) is an essential transporter of a thyroid hormone and a holo-retinol binding protein, found abundantly in human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. In addition, this protein is infamous for its amyloidogenic propensity, causing various amyloidoses in humans, such as senile systemic amyloidosis, familial amyloid polyneuropathy, and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy. Decreased stability of the native tetrameric conformation and subsequent misfolding of TTR is the main cause of these diseases.

- transthyretin misfolding

- transthyretin amyloidosis

- protein misfolding

- amyloid

1. Introduction

Transthyretin (TTR) is a transporter of thyroxine (T

4, a thyroid hormone) and a holo-retinol binding protein, from which its name has originated (TRANSporter of THYroxine and RETINol) [1][2][3]. TTR is abundant in the human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In plasma, it is mainly produced in the liver at 3–5 μM, whereas in CSF, it is mostly made in the choroid plexus at 0.25–0.5 μM [4][5]. TTR is the first and the second major transporter of T

, a thyroid hormone) and a holo-retinol binding protein, from which its name has originated (TRANSporter of THYroxine and RETINol) [1,2,3]. TTR is abundant in the human plasma and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). In plasma, it is mainly produced in the liver at 3–5 μM, whereas in CSF, it is mostly made in the choroid plexus at 0.25–0.5 μM [4,5]. TTR is the first and the second major transporter of T

4 in human CSF and plasma, respectively [6]. TTR production in the retina and pancreas has also been reported [7][8].

in human CSF and plasma, respectively [6]. TTR production in the retina and pancreas has also been reported [7,8].

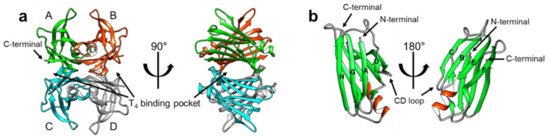

TTR has a β-strand-rich secondary structure; eight β-strands form two β-sheets (CBEF and DAGH), stacking with each other to establish a β-sandwich tertiary structure, with a short α-helix between the β-strands E and F (

). Its functionality as a T

4

transporter originates from the quaternary structure. In its native state, TTR forms a tetrameric complex, giving rise to two hydrophobic pockets for binding T

4

(

Figure 1) [9][10]. The tetrameric architecture of TTR is maintained as a dimer of dimers; one dimeric interface between the subunits AC and BD is maintained by an extensive hydrogen-bond network involving the β-strands F and H, whereas the other dimeric interface between the subunits AB and CD is stabilized mainly by hydrophobic interactions (

) [9,10]. The tetrameric architecture of TTR is maintained as a dimer of dimers; one dimeric interface between the subunits AC and BD is maintained by an extensive hydrogen-bond network involving the β-strands F and H, whereas the other dimeric interface between the subunits AB and CD is stabilized mainly by hydrophobic interactions (

a), thus, efficiently constituting the optimal binding pockets for T

4

[11]. Notably, most structural models of TTR (

) were determined by X-ray crystallography, indicating that structural heterogeneity, which may exist in a physiological condition, could not be properly reflected to these models due to the crystal symmetry and packing artifacts.

Figure 1.

a

4

b

a

In addition to its physiological functions, TTR has also attracted attention owing to its pathological features of aggregating and forming amyloid fibrils. Since the identification of TTR in human amyloid deposits in the 1970s [12], TTR amyloidosis has been shown to be strongly correlated with several amyloidoses. For example, senile systemic amyloidosis is known to be caused by spontaneous aggregation of TTR [13], whereas familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) [14] and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy (FAC) [15] are caused by genetic mutations in TTR. More than 100 TTR mutations have been reported to date, many of which facilitate pathogenic aggregation and amyloid formation [16]. Notably, a recent study estimated that 3% of the African American population has the V122I mutation, which can cause TTR cardiac amyloidosis [17][18], and 8% of the patients suspected to have cardiac amyloidosis were reported to have pathogenic TTR mutations [19].

In addition to its physiological functions, TTR has also attracted attention owing to its pathological features of aggregating and forming amyloid fibrils. Since the identification of TTR in human amyloid deposits in the 1970s [12], TTR amyloidosis has been shown to be strongly correlated with several amyloidoses. For example, senile systemic amyloidosis is known to be caused by spontaneous aggregation of TTR [13], whereas familial amyloid polyneuropathy (FAP) [14] and familial amyloid cardiomyopathy (FAC) [15] are caused by genetic mutations in TTR. More than 100 TTR mutations have been reported to date, many of which facilitate pathogenic aggregation and amyloid formation [16]. Notably, a recent study estimated that 3% of the African American population has the V122I mutation, which can cause TTR cardiac amyloidosis [17,18], and 8% of the patients suspected to have cardiac amyloidosis were reported to have pathogenic TTR mutations [19].

Many biochemical and biophysical studies have been conducted to investigate the amyloidogenic (amyloid-forming) properties of TTR, and it is generally accepted that the tertiary and quaternary stability of TTR correlates with its amyloidogenic propensity [20]. In particular, in vitro turbidity and thioflavin T fluorescence experiments showed that the tetrameric stability of TTR diminished dramatically under mild acidic conditions, which resulted in its dissociation to monomeric species and the subsequent accumulation of amyloid fibrils [21][22]. It was also reported that a molecule that binds to the T

Many biochemical and biophysical studies have been conducted to investigate the amyloidogenic (amyloid-forming) properties of TTR, and it is generally accepted that the tertiary and quaternary stability of TTR correlates with its amyloidogenic propensity [20]. In particular, in vitro turbidity and thioflavin T fluorescence experiments showed that the tetrameric stability of TTR diminished dramatically under mild acidic conditions, which resulted in its dissociation to monomeric species and the subsequent accumulation of amyloid fibrils [21,22]. It was also reported that a molecule that binds to the T

4-binding site could stabilize the tetrameric state and suppress the aggregation of TTR efficiently [23]. By conducting extensive biochemical and biophysical studies on the TTR-ligand complexes, Kelly et al. succeeded in developing a ‘kinetic stabilizer’ to stabilize the tetrameric state of TTR and suppress/prevent its aggregation [24][25]. Tafamidis, a kinetic stabilizer designed to target the T

-binding site could stabilize the tetrameric state and suppress the aggregation of TTR efficiently [23]. By conducting extensive biochemical and biophysical studies on the TTR-ligand complexes, Kelly et al. succeeded in developing a ‘kinetic stabilizer’ to stabilize the tetrameric state of TTR and suppress/prevent its aggregation [24,25]. Tafamidis, a kinetic stabilizer designed to target the T

4-binding site, is an effective drug that is currently approved for clinical use [26][27][28].

-binding site, is an effective drug that is currently approved for clinical use [26,27,28].

However, despite the central role of structural investigations in the development of novel therapeutics, initial structural studies concentrated more on the tetrameric conformation, and provided limited information to reveal the mechanistic details pertaining to TTR aggregation [29][30]. Rather, recent investigations on the structural states of TTR revealed that the protein, either in its stable tetrameric state or in the less stable monomeric state, adopts significant structural heterogeneity, which is strongly associated with many of its physiological and pathological features [31].

However, despite the central role of structural investigations in the development of novel therapeutics, initial structural studies concentrated more on the tetrameric conformation, and provided limited information to reveal the mechanistic details pertaining to TTR aggregation [29,30]. Rather, recent investigations on the structural states of TTR revealed that the protein, either in its stable tetrameric state or in the less stable monomeric state, adopts significant structural heterogeneity, which is strongly associated with many of its physiological and pathological features [31].

2. Deformation of the TTR Quaternary Structure

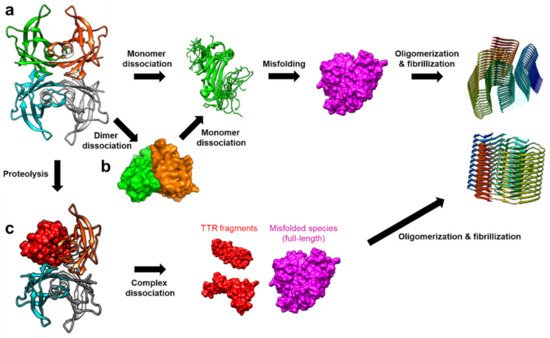

TTR amyloidosis is initiated by the dissociation of the tetramer into monomers, which is followed by deformation into misfolded monomers, non-native oligomers, and finally amyloid fibrils (

) [20]. In this section, recent advancements in revealing details regarding various non-native conformational states of TTR are discussed. Particularly, in addition to numerous structural studies on TTR tetramers, novel findings on the other quaternary states of TTR are discussed focusing on their physiological and pathological aspects.

Figure 2.

a

b

c

2.1. Conformational States of TTR Monomers

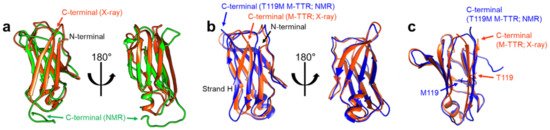

Structural features of TTR monomers were recently revealed using solution-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. Compared with X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy is advantageous for investigating dynamic molecules in a solution state. By employing this technique, solution structural models of two monomeric variants, viz., TTR(F87M/L110M; M-TTR) and TTR(F87M/L110M/T119M; T119M M-TTR), were determined at an atomic resolution [34][35]. M-TTR was designed to stabilize the monomeric state of TTR [36], whereas the T119M substitution is a structure-stabilizing mutation that effectively suppresses the amyloidogenic property of TTR [37][38]. A previous X-ray crystallographic study of M-TTR showed that it tetramerized under crystallization conditions, and its tertiary structure was highly similar to that of wild-type (WT) TTR [36]. In contrast, NMR spectroscopy revealed that both M-TTR [35] and T119M M-TTR [34] stabilized to monomeric states with different secondary and tertiary structures (

Figure 3). Notably, considering the highly dynamic characteristics of M-TTR [39], high-pressure NMR was used to reduce structural heterogeneity and improve the spectral quality [40]. Pressurized conditions were previously employed to investigate the intermediate tetrameric and monomeric states of TTR [41][42][43]. The NMR structural model of M-TTR was characterized by the loss of the final β-strand H, which forms a stable dimeric interface in the tetrameric state, and significant structural alteration of the FG loop (the loop between the β-strands F and G) (

Figure 3.

a

b

c

Notable implications of these results come from one of the initial studies that attempted to identify the amyloidogenic region of TTR. Gustavsson et al. found that the peptide originating from residues 105–115 of TTR, corresponding mostly to the β-strand G, was highly amyloidogenic [44]. Since then, amyloid fibrils made from this peptide have been used as a model to investigate their amyloidogenic features [45][46]. Therefore, this indicates that the β-strand H may play a protective role in minimizing exposure of the amyloidogenic β-strand G, whereas monomeric TTR cannot benefit from this protective effect, thus, becoming more prone to aggregation.

19

Another intriguing point regarding the structural deformation of monomeric TTR is that α-sheets, transient secondary structures that have been observed in several amyloidogenic proteins [55][56], were proposed as intermediate structures of monomeric TTR in its aggregation pathway [57]. Steward et al. reported that amyloidogenic variants of TTR were able to manifest α-sheet structures in the aggregation-prone state [58]. More recently, MD simulation data have indicated that TTR tetramer dissociation facilitates the formation of α-sheet structures on the TTR monomer, which is followed by its aggregation [59]. Based on these observations, Daggett et al. designed α-sheet peptides that are complementary to α-sheet structures of amyloid-β and TTR, and confirmed their activity against amyloidosis [60][61], supporting the hypothesis that α-sheet structures are an intermediate state in the amyloidosis pathway.

2.2. TTR Dimers

4-binding pockets. This observation is consistent with that of Foss et al. in that the dimeric species only maintain the hydrogen-bonded interface, not the hydrophobic interface [32]. Subsequent neutron crystallographic studies further confirmed that S112 of WT TTR is involved in forming a network of hydrogen bonds at the hydrophobic interface between AC and BD [52][63]. Notably, MD simulation study of S117E M-TTR (i.e., TTR[F87M/L110M/S117E]) showed that the tetrameric complex of this construct readily dissociated and formed the relatively stable AB and CD dimers [64]. Furthermore, a recent native mass-spectrometry and surface-induced dissociation study, following subunit exchange with untagged and tagged TTR proteins, revealed that the dimeric state is an intermediate for tetramers to be dissociated into monomers [65].

2.3. Oligomerization and Amyloid Formation

Small nonfibrillar oligomers have been observed with various TTR variants in the amyloid formation pathway, suggesting that these oligomers may be responsible for the significant cytotoxicity of TTR aggregates [69][70]. Investigation of TTR oligomers has been challenging due to their transient nature. Yet, there have been recent advancements in understanding their structural features. Faria et al. used SEC-coupled multiangle light scattering to reveal that transient TTR oligomers consisting of 6–10 monomers were formed in the acid-induced aggregation of TTR [71]. As discussed above, Dasari et al. also observed the formation of several oligomeric species in acid-induced aggregation experiments at 4 °C [67]. They used SEC analysis to purify the oligomeric species and analyzed them with circular dichroism to find that the secondary structural features of oligomers were more disordered than those of the native tetramers. Using solid-state NMR analysis, Dasari et al. further confirmed that, although certain regions remained rigid and unchanged, the oligomers exhibited a more extended disorder in their overall structure than the native tetramer. High-resolution AFM analysis by Pires et al. indicated that WT TTR formed annular oligomers of ~16 nm as early intermediates in the amyloidosis at pH 3.6 [72]. Intriguingly, subsequent detailed analysis of AFM images suggested that annular oligomers are likely composed of double stacks of octamers and exhibit a tendency to convert into spheroidal oligomers consisting of 8–16 monomers. In addition, Pires et al. observed that the protofibrils, linear fibrillar intermediates that were often formed from a soluble oligomer, showed a periodic structure, suggesting the presence of ~15-nm subunits. This observation indicated that the protofibril might be formed by the mechanism of adding 15-nm oligomers to the end of the protofibril [73]. More recently, Frangolho et al. used photo-induced crosslinking experiments to capture up to octameric species during acid-induced TTR aggregation at pH 3.6 [74]. They found that amyloidogenic variants of TTR showed faster oligomerization rates, and also provided evidence supporting sequential monomeric addition to oligomers.

Small nonfibrillar oligomers have been observed with various TTR variants in the amyloid formation pathway, suggesting that these oligomers may be responsible for the significant cytotoxicity of TTR aggregates [69,70]. Investigation of TTR oligomers has been challenging due to their transient nature. Yet, there have been recent advancements in understanding their structural features. Faria et al. used SEC-coupled multiangle light scattering to reveal that transient TTR oligomers consisting of 6–10 monomers were formed in the acid-induced aggregation of TTR [71]. As discussed above, Dasari et al. also observed the formation of several oligomeric species in acid-induced aggregation experiments at 4 °C [67]. They used SEC analysis to purify the oligomeric species and analyzed them with circular dichroism to find that the secondary structural features of oligomers were more disordered than those of the native tetramers. Using solid-state NMR analysis, Dasari et al. further confirmed that, although certain regions remained rigid and unchanged, the oligomers exhibited a more extended disorder in their overall structure than the native tetramer. High-resolution AFM analysis by Pires et al. indicated that WT TTR formed annular oligomers of ~16 nm as early intermediates in the amyloidosis at pH 3.6 [72]. Intriguingly, subsequent detailed analysis of AFM images suggested that annular oligomers are likely composed of double stacks of octamers and exhibit a tendency to convert into spheroidal oligomers consisting of 8–16 monomers. In addition, Pires et al. observed that the protofibrils, linear fibrillar intermediates that were often formed from a soluble oligomer, showed a periodic structure, suggesting the presence of ~15-nm subunits. This observation indicated that the protofibril might be formed by the mechanism of adding 15-nm oligomers to the end of the protofibril [73]. More recently, Frangolho et al. used photo-induced crosslinking experiments to capture up to octameric species during acid-induced TTR aggregation at pH 3.6 [74]. They found that amyloidogenic variants of TTR showed faster oligomerization rates, and also provided evidence supporting sequential monomeric addition to oligomers.

In addition to structural studies on oligomers, significant advancements have been made in elucidating the structural details of TTR amyloid fibrils. Cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) of TTR amyloid fibrils, collected from a patient suffering from hereditary TTR(V30M) amyloidosis, revealed that the structural features of TTR amyloid fibrils are fairly distinct from their native structure, suggesting severe structural alterations during TTR aggregation [75]. In comparison, solid-state NMR approaches have suggested that the native-like β-strand architectures of TTR are maintained at least in a part of amyloid fibrils that are formed under acidic conditions [76], along with local structural changes in the AB loop [48]. A subsequent study found that amyloid fibrils formed from amyloidogenic variants, such as V30M and L55P TTR, have distinctive structural states in the β-strands A and D [77]. This discrepancy between cryo-EM and solid-state NMR results, along with another solid-state NMR structural model of the amyloid fibrils made with TTR(105-115) peptides [78], needs to be further elucidated. Yet, it may indicate heterogeneous amyloidosis mechanisms of TTR that are likely to depend on factors such as genetic variations and conditions of aggregation.