The transient receptor potential melastatin (TRPM) family belongs to the superfamily of TRP ion channels. It consists of eight family members that are involved in a plethora of cellular functions. TRPM2 is a homotetrameric Ca2+-permeable cation channel activated upon oxidative stress and is important, among others, for body heat control, immune cell activation and insulin secretion. Invertebrate TRPM2 proteins are channel enzymes; they hydrolyze the activating ligand, ADP-ribose, which is likely important for functional regulation. Since its cloning in 1998, the understanding of the biophysical properties of the channel has greatly advanced due to a vast number of structure–function studies. The physiological regulators of the channel have been identified and characterized in cell-free systems. In the wake of the recent structural biochemistry revolution, several TRPM2 cryo-EM structures have been published. These structures have helped to understand the general features of the channel, but at the same time have revealed unexplained mechanistic differences among channel orthologues.

- TRPM2

- ion channels

- single particle cryo-EM

- ADP-ribose

- Nudix hydrolase

1. Introduction

TRPM2 channels are widely expressed in bone marrow, the heart, liver, pancreas, leukocytes, lungs, spleen, eye, and brain [5][6][7]. TRPM2 is a nonselective cation channel which is co-activated by ADP-ribose (ADPR) and Ca

2+

2+, TRPM2 is also involved in many pathophysiological processes that lead to cell death [11], including neuronal cell death upon reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and in neurodegenerative disorders [5][12][13][14]. Hence, TRPM2 has become an attractive pharmacological target.

TRPM2 is a homotetramer; its subunits are built from ~1500 amino acid residues and consist of a large cytosolic N-terminal region, followed by a transmembrane domain (TMD) and a cytosolic C-terminal region. Both the intracellular and transmembrane regions are involved in ligand binding. The TMD contains six transmembrane helices (S1–6), and its structural organization resembles that of voltage-dependent cation channels [15][16]. In voltage-gated K

+

5

7

2+

2+

+

2. Characterization of TRPM2 in a Cell-Free System and Identification of Direct Effectors

2.1. Activation of TRPM2 by ADPR, Ca2+ and Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2)

2+ [7][26][27][28][29]. As in whole-cell studies the composition of the cytosolic solution, and particularly that of microdomains, is not strictly controlled, the location of the activating Ca

2+ binding sites (extra- or intracellular) could not be unambiguously determined [27][29]. In contrast, inside-out patch clamp recordings afford strict control over the composition of the cytosolic solution, and rapid application/removal (on the timescale of tens of milliseconds) of intracellular ligands. In patches excised from

Xenopus laevis

2+

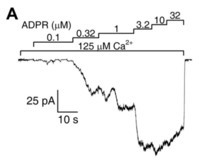

Figure 1A) [30][31]. Both ligands were required for channel activity, but interestingly, effective concentrations differed from those published earlier in studies using whole cells [7][24][26][27][28][29]. Whereas in whole-cell recordings EC

50

2+ were ~100 μM and ~300 nM, respectively [7][27], in inside-out patches, ADPR apparent affinity was two orders of magnitude higher (EC

50

2+

50~20 μM), and these apparent affinities were little affected by the concentration of the other ligand [30][31]. A possible explanation for a lower Ca

2+ affinity could have been the loss of calmodulin in the patch (cf [29][32]); however, the addition of external bovine calmodulin had no effect on fractional currents at micromolar Ca

2+

2+

2+

Figure 1.

A

+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2+

2

2

2+ [33] or by administration with external PIP

2 [34]. While H

2

2 potently stimulates TRPM2 currents in intact cells [5][26][35], this effect must be a secondary consequence of ADPR and/or Ca

2+ release in response to the induced oxidative stress [35], as H

2

2

2.2. Pyridine Nucleotides and Their Derivatives Are Not Direct Activators of TRPM2

In the body, CD38, a multifunctional glycoprotein enzyme present on the surface of immune cells, converts the pyridine nucleotides NAD and NAAD into ADPR, but NADP and NAADP into ADPR-2-phosphate (ADPRP) [36]. These nucleotides and others, the metabolism of which is intertwined with that of ADPR, were tested to address the potential effects on TRPM2. NAD was identified as a channel agonist in early studies [5][28], while no binding to the NUDT9-H domain was later reported [24]. NAAD [31], NAADP [31][37][38] and cADPR [37][38] were reported to act as activators, AMP as an inhibitor [24][26], while NADH and NADP were found to be ineffective [5]. Besides these reported effects on channel activity, cADPR [26][37][38] and NAADP [37][38] were also shown to augment the effects of ADPR in a positively cooperative manner. 8-Br-cADPR, an agent shown to reduce ischæmic acute kidney injury [37], was suggested to act as a partial TRPM2 agonist and a competitive inhibitor of activation by cADPR [26]. Most of the above studies examined the effects of nucleotides in whole-cell systems. In a study in inside-out patches, the effects of cADPR on TRPM2 channel activity were shown to be attributable to ADPR contamination [31]. Decontamination of commercial cADPR stocks with a nucleotide pyrophosphatase which selectively cleaves ADPR but not cADPR eliminated channel stimulation by the compound in excised patches. Furthermore, no cooperative effects of cADPR with ADPR were observed. Recently, Yu et al reported that synthetic pure cADPR directly binds to the human NUDT9-H domain [39]. SPR titration indicated an apparent affinity (K

d

50 ~250 μM) were required to stimulate macroscopic TRPM2 currents. Considering its submicromolar cellular concentration [40], cADPR does not seem to act as a physiological activator of TRPM2. TRPM2 channel activation by various pyridine dinucleotides is explained by their spontaneous degradation, which also produces ADPR(P). Cleavage of contaminating ADPR in NAD and NAAD stocks, or of contaminating ADPRP in NAADP stocks, by the purified NUDT9 ADPRase abolished the stimulatory effects of the dinucleotides, ruling them out as direct effectors of TRPM2 [41]. Moreover, these experiments also demonstrated that none of the spontaneous and/or enzymatic cleavage products—nicotinamide, nicotinic acid, AMP(P) or ribose-5-phosphate—are TRPM2 channel activators. An apparent stimulatory effect of NAADP prior to decontamination pinpointed its spontaneous degradation product ADPRP as an agonist. Indeed, in inside-out patches, pure ADPRP opened TRPM2 channels, albeit its apparent affinity was lower (EC

50~13 μM) and maximal stimulation smaller (~80%) when compared to ADPR. The lower open probability supported by ADPRP was explained by an approximately three-times faster macroscopic closing rate, reflecting a shortened open burst [41]. A similar efficacy but even lower affinity (EC

50~110 μM) for ADPRP was reported in a whole-cell study [42] that also showed 2’-deoxy-ADPR (dADPR) to act as a superagonist on hsTRPM2 channels. In the presence of dADPR, whole-cell TRPM2 currents were 37% larger, and following patch excision channels inactivated slower, but the EC

50

In summary, recordings in cell-free systems demonstrated that (d)ADPR is a physiologically relevant activator of the hsTRPM2 channel and ADPRP is a partial agonist, whereas AMP and pyridine dinucleotides are without effect [31][41] and cADPR is probably a non-physiological low affinity agonist [39]. Note, however, that nucleotide affinity and efficacy profiles differ among channel orthologues.