Diabetes mellitus is a widespread disease, and represents an important public health burden worldwide. Together with cardiovascular, renal and neurological complications, many patients with diabetes present with gastrointestinal symptoms, which configure the so-called diabetic enteropathy.

- dyspepsia

- diabetes

- gastroparesis

1. Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is a widespread disease. According to the last estimate from the International Diabetes Federation (ID) it affects 463 million people worldwide with increasing prevalence [1]. DM represents an important public health burden, mainly because of its cardiovascular, renal and neurological complications. In addition, many patients with diabetes present with upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and motility alterations. Among the latter, delayed gastric emptying (GE) affects up to 50% of patients with both type 1 and type 2 DM manifesting with dyspepsia, gastroparesis or, for a proportion of patients, remaining asymptomatic [2]. As dyspepsia and diabetic gastroparesis (DG) share similar pathogenetic mechanisms and clinical features, the differential diagnosis may be challenging. Recently, some authors suggested that functional dyspepsia (FD) and DG could be different expressions of the same spectrum of gastric neuromuscular disorders, with common histopathological alterations and comparable clinical manifestations and prognosis [3].

2. Dyspepsia: Definition and Clinical Classification

The term dyspepsia includes a set of symptoms with epigastric localization, which can be episodic or persistent, with variable intensity and severity. In the clinical setting, it is often difficult to characterize these symptoms and to distinguish dyspepsia from other GI disorders such as gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [4]. The American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) and Canadian Association of Gastroenterology (CAG) clinical guidelines give a useful definition of dyspepsia as predominant epigastric pain which lasts at least one month and is associated with any other upper GI symptom such as epigastric fullness, nausea, vomiting or heartburn [5].

For the appropriate clinical management, it is important to distinguish organic dyspepsia from FD. The former includes patients in whom clinical evaluation, laboratory tests, endoscopy or radiologic studies can identify a pathologic process which is the cause of dyspeptic symptoms, while FD includes all cases of dyspepsia without evidence of an organic cause [6]. The exclusion of organic causes requires endoscopy and, where needed, radiologic investigations, such as ultrasound or computed tomography, along with Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) testing and treating and re-evaluation of symptoms after its eradication [7].

Functional dyspepsia can be classified on the basis of prevalent symptoms in postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) [8]. These two entities, however, have blurred boundaries as they frequently overlap and they share similar therapeutic strategies. Moreover, due to their common motility alterations, PDS is more likely to overlap with gastroparesis.

Although different definitions of FD have been previously proposed, the most recent update is represented by Rome IV criteria, shown in Table 1 [9].

Table 1. Rome IV diagnostic criteria of functional dyspepsia modified from [9].

|

Functional Dyspepsia: |

AND

a. Must fulfill criteria for PDS (Postprandial Distress Syndrome) and/or EPS (Epigastric Pain Syndrome). b. Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. |

|

Postprandial Distress Syndrome (PDS): |

|

1. One or both of the following for at least 3 days per week and severe enough to impact on usual activities: (a) postprandial fullness (b) early satiation 2. No evidence of organic, systemic, or metabolic disease which can explain symptoms. Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis. Supportive remarks:

|

|

Epigastric Pain Syndrome(EPS): |

|

1. One or both of the following for at least 1 day per week and severe enough to impact on usual activities: (a) epigastric pain (b) epigastric burning 2. No evidence of organic, systemic, or metabolic disease which can explain symptoms Criteria fulfilled for the last 3 months with symptom onset at least 6 months before diagnosis Supportive remarks:

|

H. pylori-associated dyspepsia represents a distinct form of dyspepsia [10]. If dyspepsia resolves six months after bacterial eradication it can be attributed to H. pylori infection [11][12][11,12] otherwise the disorder is deemed FD [7].

3. Dyspepsia in Diabetic Patients

Dyspeptic symptoms are a frequent finding in patients with diabetes and they are part of the so-called diabetic enteropathy (DE), which includes the GI manifestations of DM [13][30]. Autonomic neuropathy has an important pathogenetic role in DE, together with interstitial cells of Cajal depletion and reduced expression of neuronal nitric oxide syntethase [13][30]. These alterations lead to abnormal GI motility, causing symptoms such as dyspepsia, nausea, vomiting, constipation and fecal incontinence.

Despite the high incidence of dyspepsia in patients with diabetes, the current literature offers limited data about the clinical features and the appropriate management of dyspepsia in this population. In case of a patient with DM presenting with upper GI symptoms, organic disease and medication side effects should be excluded: GLP-1 analogues, for example, can cause nausea and vomiting [13][30]. Moreover, DG should be excluded through GE measurement, as discussed below [2][14][2,31]. When organic dyspepsia, medication side effects and DG are excluded, the clinical management is analogous to that of non-diabetic patients, except for a more important therapeutic role of prokinetics in patients with DM.

4. H. pylori Infection in Patients with Diabetes

Many studies have analyzed the prevalence of H. pylori infection in symptomatic and asymptomatic patients with DM [15][16][17][32,33,34]. Hyperglycemia has been suggested as a predisposing factor for H. pylori colonization [15][32]. A recent case–control serological study demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of H. pylori infection in patients with DM, who had positive antibody titers in 50.7% of cases, compared to 38.2% of controls [16][33]. Moreover, H. pylori positive patients showed higher incidence of GI symptoms, including bloating, distention, vomiting, abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhea, as well as systemic manifestations such as hypertension, muscular symptoms and chronic bronchitis, which is potentially attributable to H. pylori contribution to inducing systemic inflammation [16][33].

Among patients with DM, H. pylori infection has been shown to be higher in patients with gastroparesis, and bacterial eradication reduced symptoms such as upper abdominal pain and distention, early satiety and anorexia [17][34], thus suggesting a pathogenetic role of H. pylori in DG and reaffirming the therapeutic role of its eradication.

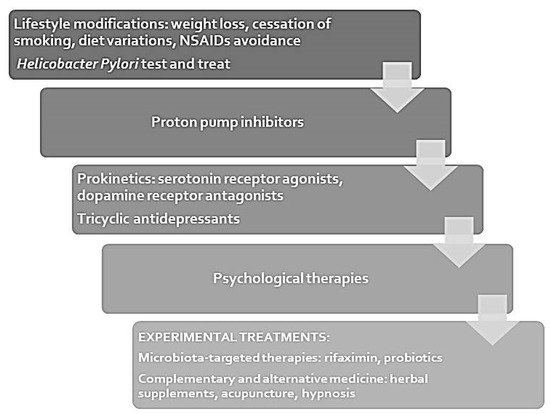

5. Clinical Management of Dyspepsia

The ACG/CAG clinical guidelines [5] provide indications on the diagnostic work-up which should be performed in patients with dyspeptic symptoms in addition to pharmacological therapies. According to guidelines, patients under the age of 60 should not undergo endoscopy to exclude malignancy, while, as previously mentioned, upper GI neoplasia should be excluded in elderly and in subjects with neoplastic risk factors [5]. The ACG/CAG clinical guidelines do not recommend the routine use of motility studies, which should only be performed in case of FD when gastroparesis is strongly suspected, as in patients with predominant symptoms of nausea and vomiting, who do not respond to empiric therapy. As discussed above, gastroparesis is diagnosed by documentation of delayed GE, investigated through GE scintigraphy or 13C-octanoic acid breath test, after exclusion of mechanical obstruction through radiologic or endoscopic examination [5].

Patients under the age of 60 should have a non-invasive test for H. pylori infection and they should be subsequently treated if the test is positive, while they should receive an empirical treatment with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) if they are H. pylori negative or they are still symptomatic after bacterial eradication [5]. Even in the absence of gastric acid secretion abnormalities, PPIs showed to be effective in relieving FD symptoms and their efficacy was not related to concomitant GERD or H. pylori positivity [18][50].

Patients with dyspepsia not responding to PPIs and H. pylori eradication, can be offered a prokinetic therapy, despite the limited effectiveness data only available in non-diabetic dyspeptic patients [5]. However, only in dyspepsia related to DE, prokinetics have shown efficacy in improving gastric motility and reducing symptoms [13][30]. Prokinetics include serotonin-4 receptor agonists such as cisapride, mosapride and tandospirone citrate, which can be effective in relieving abdominal pain [19][51] and dopamine-2 receptor antagonists, like metoclopramide, which have shown efficacy similar to cisapride in improving GE and a better control of nausea, vomiting and early satiety [20][52]. However, metoclopramide is associated with important side effects, including hyperprolactinemia, closely related to gynecomastia and galactorrhea, and extrapyramidal symptoms, such as drug-induced parkinsonism and tardive dyskinesia [2].

Acotiamide is a prokinetic, currently approved for use in Japan and India for FD. It inhibits pre-sinaptic acetil-cholinesterase and antagonized presynaptic M1 and M2 receptors and it seems to relieve PDS symptoms, with a good tolerability [21][22][53,54].

An alternative to prokinetic drugs is represented by neuromodulators. In fact, triciclic antidepressant therapy (TCAs), such as amitriptyline, showed to relieve abdominal pain and improve the quality of life in patients with dyspepsia [23][24][55,56]. Data on serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) are controversial as some studies showed an efficacy similar to TCAs [25][57], while other studies did not demonstrate any efficacy in symptom relief [21][53]. In the clinical setting the decision between prokinetics and TCAs should be made on a case-by-case basis [5].

As previously discussed, microbiota is receiving increasing attention in the context of FD and some authors have studied a potential effect of therapies targeting on gut microbiota, such as rifaximin [26][58] or supplementation with Lactobacillus strains [27][59], which act restoring the physiological microbiota. However, data about the indication to treat dyspeptic patients with probiotics remain scarce.

Finally, patients with FD not responding to drug therapy should be offered psychological therapies. Considering the role of psychological factors in the development of FD, in fact, these treatments may provide a significant symptom relief [10]. The quality of evidence about this approach is very low and the available studies are heterogeneous and do not suggest a specific psychological intervention [5].

Some authors have also proposed complementary and alternative treatments, such as herbal supplements, acupuncture and hypnosis [10], however, the available data are limited and more studies are needed to assess the efficacy of these therapies.

The above discussed therapeutic options for FD are summarized in Figure 1. Together with these pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches, remains crucial the therapeutic role of lifestyle modifications, such as weight loss in obese patients, cessation of smoking, diet variations, NSAIDs avoidance [10]. These interventions represent the first step in FD treatment and should be associated with any other therapy.

Figure 1. Treatment algorithm for functional dyspepsia.