Linusorbs (LOs) are natural peptides found in flaxseed oil that exert various biological activities. Of LOs, LOB3 ([1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3) was reported to have antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities; however, its anti-cancer activity has been poorly understood. Therefore, this study investigated the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 and its underlying mechanism in glioblastoma cells.

- Flaxseed oil

- linusorb B3

- anti-cancer

- apoptosis

- actin polymerization

- Src

- glioblastoma

1. Introduction

Glioma is a general term describing brain tumors and includes astrocytic tumors (astrocytomas), oligodendrogliomas, ependymomas, brain stem gliomas, optic pathway gliomas, and mixed gliomas [1]. About one-third of total brain tumors are gliomas originating in the glial cells that surround and support nerve cells in the brain, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and ependymal cells. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), a grade IV astrocytoma, is the most aggressive type of cancer that develops primarily in the brain and spreads into nearby brain tissue. GBM accounts for around 60% of the total primary brain tumors in adults [2]. The annual incidence rate of GBM is up to 5 per 100,000 persons worldwide, and the average survival time is 12–18 months with less than 10% 5-year survival rates after standard treatment [3]. GBM can occur at a broad range of ages but tends to occur more in older adults between the age of 45 and 70, and the mean age for death from brain cancers and other regions of the central nervous system was is 64. GBM diagnosis includes sophisticated imaging techniques, such as computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. GBM can be very difficult to treat and a cure is often not possible. Treatments of GBM may slow cancer progression and reduce the signs and symptoms, but there are no known methods to prevent GBM. Current standard treatment usually involves radiation and chemotherapy therapy followed by surgery [4,5,6]. Surgery removes as much of the tumors as possible, but GBM grows into the normal tissue, so complete removal is not possible [7]. Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells and is usually recommended after surgery in the combination with chemotherapy [7]. Chemotherapy uses medications to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy is also recommended after surgery and is often used during and after radiation therapy [7]. Immunotherapy of GBM is also being studied using programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors [8,9,10]. Preclinical studies in GBM mouse models showed the safety and efficacy, including significant tumor regression and longer survival rate of monoclonal antibody therapeutics targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis [8]. Currently, monoclonal antibody therapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis is being evaluated in clinical trials concerning GBM patients. However, despite recent medical and surgical advances, treatment of GBM remains very difficult, with poor prognoses and disappointingly low survival rates, and one of the critical concerns of the current chemotherapy is a toxicity issue, which raises the demand for the development of more effective and less toxic medications, such as the natural product-derived complementary and alternative medicines to treat GBM.

Glioma is a general term describing brain tumors and includes astrocytic tumors (astrocytomas), oligodendrogliomas, ependymomas, brain stem gliomas, optic pathway gliomas, and mixed gliomas [1]. About one-third of total brain tumors are gliomas originating in the glial cells that surround and support nerve cells in the brain, such as astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and ependymal cells. Glioblastoma multiforme (GBM), a grade IV astrocytoma, is the most aggressive type of cancer that develops primarily in the brain and spreads into nearby brain tissue. GBM accounts for around 60% of the total primary brain tumors in adults [2]. The annual incidence rate of GBM is up to 5 per 100,000 persons worldwide, and the average survival time is 12–18 months with less than 10% 5-year survival rates after standard treatment [3]. GBM can occur at a broad range of ages but tends to occur more in older adults between the age of 45 and 70, and the mean age for death from brain cancers and other regions of the central nervous system was is 64. GBM diagnosis includes sophisticated imaging techniques, such as computer tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. GBM can be very difficult to treat and a cure is often not possible. Treatments of GBM may slow cancer progression and reduce the signs and symptoms, but there are no known methods to prevent GBM. Current standard treatment usually involves radiation and chemotherapy therapy followed by surgery [4][5][6]. Surgery removes as much of the tumors as possible, but GBM grows into the normal tissue, so complete removal is not possible [7]. Radiation therapy uses high-energy radiation to kill cancer cells and is usually recommended after surgery in the combination with chemotherapy [7]. Chemotherapy uses medications to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy is also recommended after surgery and is often used during and after radiation therapy [7]. Immunotherapy of GBM is also being studied using programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1)/PD ligand 1 (PD-L1) immune checkpoint inhibitors [8][9][10]. Preclinical studies in GBM mouse models showed the safety and efficacy, including significant tumor regression and longer survival rate of monoclonal antibody therapeutics targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis [8]. Currently, monoclonal antibody therapy targeting PD-1/PD-L1 axis is being evaluated in clinical trials concerning GBM patients. However, despite recent medical and surgical advances, treatment of GBM remains very difficult, with poor prognoses and disappointingly low survival rates, and one of the critical concerns of the current chemotherapy is a toxicity issue, which raises the demand for the development of more effective and less toxic medications, such as the natural product-derived complementary and alternative medicines to treat GBM.

Flax (

Linum usitatissimum

L.), also known as linseed, is a fibrous crop and bluish-flowering plant that belongs to the family

Linaceae. It has been cultivated as a fiber crop and food (flaxseed) in cooler regions of countries, such as Canada, China, and Russia for a long time and is also used in Ayurvedic medicines [11]. Flax is originally cultivated for its fiber, and flax fiber has long been used for manufacturing linen, fabrics, yarn, cordage in many textile industies [12]. Flax is also cultivated for flaxseed. Flaxseed contains 20–25% proteins and 40–45% fatty acids, including the major bioactive ingredients, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids, short-chain omega-3, lignan, mucilage, and linusorbs (LOs) [13]. Flaxseed has been consumed as a dietary supplement for human health and herbal medicines with the purpose of ameliorating many human diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, renal disease, cancers, diabetes, stroke, skin disease, gastrointestinal disease, and inflammatory diseases [11,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24]. Flaxseed has been also used for extracting flaxseed oil that is the oldest commercial oil for foods and pharmaceutical purposes, and flaxseed oil contains many bioactive ingredients such as omega-3 fatty acids, alpha-linolenic acid, lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, and LOs [11,25]. LOs, whose name is derived from

. It has been cultivated as a fiber crop and food (flaxseed) in cooler regions of countries, such as Canada, China, and Russia for a long time and is also used in Ayurvedic medicines [11]. Flax is originally cultivated for its fiber, and flax fiber has long been used for manufacturing linen, fabrics, yarn, cordage in many textile industies [12]. Flax is also cultivated for flaxseed. Flaxseed contains 20–25% proteins and 40–45% fatty acids, including the major bioactive ingredients, such as polyunsaturated fatty acids, short-chain omega-3, lignan, mucilage, and linusorbs (LOs) [13]. Flaxseed has been consumed as a dietary supplement for human health and herbal medicines with the purpose of ameliorating many human diseases, including cardiovascular diseases, hypertension, renal disease, cancers, diabetes, stroke, skin disease, gastrointestinal disease, and inflammatory diseases [11][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24]. Flaxseed has been also used for extracting flaxseed oil that is the oldest commercial oil for foods and pharmaceutical purposes, and flaxseed oil contains many bioactive ingredients such as omega-3 fatty acids, alpha-linolenic acid, lignan secoisolariciresinol diglucoside, and LOs [11][25]. LOs, whose name is derived from

L. usitatissimum, are natural bioactive orbitide consisting of eight, nine or ten amino acid residues with a molecular weight of approximately 1 kDa and can also be found in flaxseed oil [20,26,27,28]. Studies have demonstrated that LOs have various biological and pharmacological activities, including immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, anti-malarial, and anti-cancer effects, [18,20,29,30]. LOB3 ([1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3) was the first LO to be discovered and isolated in flaxseed in 1959 [30] and is the most abundant cyclic nonapeptide. LOB3 and its analogs were reported to have pharmacological properties in disease conditions, such as antioxidative, immunosuppressive, anti-malarial, and anti-inflammatory properties [20,31,32,33]. A few studies have reported that LOB3 also shows cytotoxic activity against several types of cancers [29,34], but its anti-cancer activity, especially anti-GBM activity, and the underlying molecular mechanisms still remain poorly understood. Therefore, the present study investigated the anti-cancer activity of LOB3 and the underlying molecular mechanism in glioblastoma cells.

, are natural bioactive orbitide consisting of eight, nine or ten amino acid residues with a molecular weight of approximately 1 kDa and can also be found in flaxseed oil [20][26][27][28]. Studies have demonstrated that LOs have various biological and pharmacological activities, including immunosuppressive, anti-inflammatory, anti-malarial, and anti-cancer effects, [18][20][29][30]. LOB3 ([1–9-NαC]-linusorb B3) was the first LO to be discovered and isolated in flaxseed in 1959 [30] and is the most abundant cyclic nonapeptide. LOB3 and its analogs were reported to have pharmacological properties in disease conditions, such as antioxidative, immunosuppressive, anti-malarial, and anti-inflammatory properties [20][31][32][33]. A few studies have reported that LOB3 also shows cytotoxic activity against several types of cancers [29][34], but its anti-cancer activity, especially anti-GBM activity, and the underlying molecular mechanisms still remain poorly understood. Therefore, the present study investigated the anti-cancer activity of LOB3 and the underlying molecular mechanism in glioblastoma cells.

2. Cytotoxic and Anti-Proliferative Effect of LOB3 in Cancer Cells

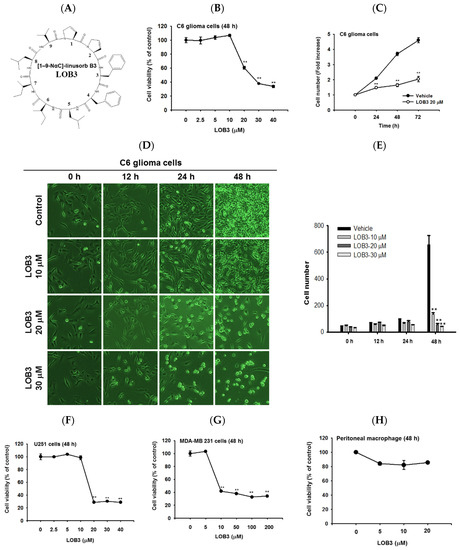

LOs are small biologically active cyclic peptides found in flaxseed oil, and many types of LOs have been identified and named based on their structures [35]. Of LOs, LOB3 (

Figure 1A, molecular weight: 1040.34) and its analogs have been demonstrated to play pivotal roles in antioxidative [31] and anti-inflammatory actions [20]. Interestingly, recent studies have reported the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells [29,34,36]; however, the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 and the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Therefore, this study investigated the anti-cancer activity of LOB3 and the underlying mechanisms in C6 glioblastoma cells, since glioblastoma multiforme is the most aggressive type of brain cancer with a high recurrence rate and a low 5-year survival rate [37].A, molecular weight: 1040.34) and its analogs have been demonstrated to play pivotal roles in antioxidative [31] and anti-inflammatory actions [20]. Interestingly, recent studies have reported the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells [29][34][36]; however, the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 and the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. Therefore, this study investigated the anti-cancer activity of LOB3 and the underlying mechanisms in C6 glioblastoma cells, since glioblastoma multiforme is the most aggressive type of brain cancer with a high recurrence rate and a low 5-year survival rate [37].

Cytotoxic and anti-proliferative effect of LOB3 in cancer cells. (

) Chemical structure of LOB3. (

) C6 cells were treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for 48 h, and cell viability was determined by a conventional 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. (

) C6 cells were treated with LOB3 (20 μM) for the indicated time, and viable cell numbers were determined by a conventional MTT assay. (

,

) C6 cells were treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for the indicated time, and cell numbers and shapes were observed under a light microscope. Photos of the cells were taken by a digital camera (

) and numbers of cells were counted by a cell counter (

). (

–

) U251, MDA-MD-231, and peritoneal macrophage cells were treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for 48 h, and cell viability was determined by a conventional MTT assay. The data (

,

,

,

–

) are expressed as the means ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of three independent experiments. Statistical significance was analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. **

< 0.01 compared to the vehicle-treated controls.

First, the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 was evaluated in C6 cells. C6 cells were treated with various doses of LOB3 for 48 h, and cell viability was examined by an MTT [3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide] assay. LOB3 from 20 to 40 μM exerted a cytotoxic effect in C6 cells in a dose-dependent manner, while no cytotoxic effect of LOB3 was shown at doses lower than 10 μM (

Figure 1B). One of the fundamental features of cancer is tumor clonality and uncontrolled proliferation. Therefore, the anti-proliferative effect of LOB3 was also evaluated in C6 cells. C6 cells treated with LOB3 (20 μM) were cultured for 72 h, and the proliferation rate of LOB3-treated C6 cells was significantly reduced compared to that of the vehicle-treated control cells (

Figure 1C). These results were confirmed by observing the shape and the numbers of C6 cells after LOB3 treatment. Similar to the results depicted in

Figure 1B,C, LOB3 exerted a cytotoxic effect in C6 cells by changing the cell shape and reducing cell numbers at 20 and 30 μM in a time- and dose-dependent manner (

Figure 1D,E).

The cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells was further investigated in another glioblastoma cell line, U251 cells, and a breast cancer cell line, MDA-MB-231 cells. Similar to the C6 cells, LOB3 significantly reduced the viability of U251 cells at doses of 20 μM and greater, but no cytotoxic effect was observed at doses lower than 10 μM (

Figure 1F). Similar to a previous study [34], LOB3 also induced the cytotoxicity of MDA-MB-231 cells, but MDA-MB-231 cells were more sensitive to LOB3. LOB3 exerted the cytotoxic effect in the breast cancer cells at doses as low as 10 μM (

Figure 1G), while the two glioblastoma cell lines were sensitive and dead at 20 μM (

Figure 1B,C,F), indicating that the drug sensitivity and cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells depend on the types of cancer cells. Furthermore, cytotoxicity of this compound was not found in non-malignant cells, peritoneal macrophages (

Figure 1H). Similarly, other natural bioactive orbitides such as surfactins and beauvericin displayed anti-cancer activity in giant-cell tumors of the bone (GCTB) cells, MCF-7 breast tumor cells, and CT-26 lymphoma [38,39,40], implying that cytotoxic activity of LOB3 might be due to structural feature of this compound. Taken together, these results suggest that LOB3 plays an anti-cancer role by inducing cytotoxicity and reducing the proliferation of cancer cells).H). Similarly, other natural bioactive orbitides such as surfactins and beauvericin displayed anti-cancer activity in giant-cell tumors of the bone (GCTB) cells, MCF-7 breast tumor cells, and CT-26 lymphoma [38][39][40], implying that cytotoxic activity of LOB3 might be due to structural feature of this compound. Taken together, these results suggest that LOB3 plays an anti-cancer role by inducing cytotoxicity and reducing the proliferation of cancer cells).

3. Cytotoxic Effect of LOB3 on C6 Cells by Apoptosis

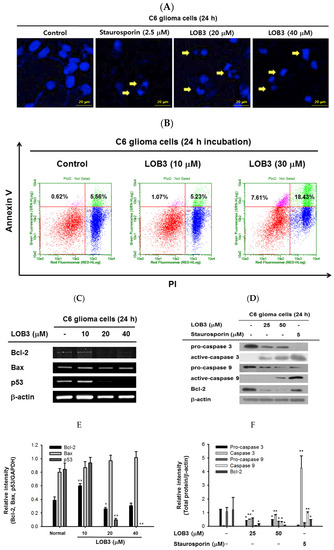

Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death occurring in multicellular organisms and is characterized by many biochemical events leading to cell changes and eventually death [41,42]. surfactins and beauvericin were reported to induce apoptosis in cancer cells [36,38,43]; therefore, whether the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells is mediated by apoptosis was evaluated in C6 cells. One of the major characteristics of apoptosis is nuclear shrinking and fragmentation [44,45], and these events were examined in LOB3-treated C6 cells by Hoechst nuclear staining. Compared to the control, LOB3 (20 and 30 μM) had a similar effect on C6 cells as staurosporine, an apoptosis inducer [46], in that it stimulated nuclear shrinking and fragmentation (Apoptosis is a form of programmed cell death occurring in multicellular organisms and is characterized by many biochemical events leading to cell changes and eventually death [41][42]. surfactins and beauvericin were reported to induce apoptosis in cancer cells [36][38][43]; therefore, whether the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on cancer cells is mediated by apoptosis was evaluated in C6 cells. One of the major characteristics of apoptosis is nuclear shrinking and fragmentation [44][45], and these events were examined in LOB3-treated C6 cells by Hoechst nuclear staining. Compared to the control, LOB3 (20 and 30 μM) had a similar effect on C6 cells as staurosporine, an apoptosis inducer [46], in that it stimulated nuclear shrinking and fragmentation (

Figure 2A). Double staining of annexin V and propidium iodide (PI) is a commonly used analytical approach for detecting apoptosis of cells [47], and this method was used to examine LOB3-induced apoptosis of C6 cells. The proportions of early and late apoptosis of LOB3-treated C6 cells were quantified by flow cytometry analysis after Annexin V/PI staining, and the results indicated that LOB3 significantly induced the apoptotic population of C6 cells at doses of 30 μM, but not 10 μM (

Figure 2B). This result is consistent with the result that LOB3 exhibited the cytotoxicity-inducing effect from doses of 20 μM (

Figure 1B,D).

Cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on C6 cells by apoptosis. (

) The nuclei of C6 cells treated with either staurosporine (2.5 μM) or LOB3 (20 and 30 μM) were stained with Hoechst 33342 and observed under a fluorescence microscope. Yellow arrows indicate nuclear shrinking and fragmentation. (

) C6 cells treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for 24 h were stained with PI and annexin V-FITC, and the cell population was determined by flow cytometry analysis. (

) C6 cells were treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for 24 h, and mRNA levels of Bcl-2, BAX, and p53 were analyzed by semiquantitative RT-PCR. (

) C6 cells were treated with either staurosporine (5 μM) or LOB3 (25 and 50 μM) for 24 h, and protein levels of pro-caspase-3, caspase-3, pro-caspase-9, and caspase-9 were determined by Western blot analysis. The data (

,

) are expressed as the means ± standard deviation (SD) of three experiments. Statistical significance was analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Results (

,

). Data of band intensity (

,

) were measured and quantified using ImageJ. *

< 0.05 and **

< 0.01 compared to the vehicle-treated controls.

The mechanism by which LOB3 exhibited an apoptotic effect on C6 cells was next evaluated at a molecular level. Bcl-2 family members play pivotal roles in the regulation of apoptosis and are categorized into two major groups: anti-apoptotic members, including Bcl-2, Bcl-X

L, Bcl-W, MCL-1, and BFL-1/A1, and pro-apoptotic members, including BAX, BAK, BOK, and BAD [48]. The effect of LOB3 on the mRNA expression of both anti-apoptotic and pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 family members was examined in C6 cells. LOB3 decreased mRNA expression of the anti-apoptotic member Bcl-2 at doses of 20 and 40 μM (

Figure 2C–F) but showed no marked effect on mRNA expression of the pro-apoptotic member BAX at all doses in C6 cells (

Figure 2C,E), suggesting that LOB3 induced apoptotic death of C6 cells by inhibiting the expression of the anti-apoptotic member, Bcl-2 rather than increasing the expression of the pro-apoptotic member, BAX. p53 is a tumor suppressor, but strong evidence has accumulated to indicate that p53 plays an anti-apoptotic role by transcriptionally activating many genes whose products efficiently suppress apoptosis [49]. Therefore, the effect of LOB3 on mRNA expression of p53 was examined, and mRNA expression of p53 was markedly decreased in the LOB3-treated C6 cells at doses of 20 and 40 μM (

Figure 2C,E).

Caspases are a family of endonucleases that act as critical links in the molecular networks that control apoptosis and play critical roles in the induction of apoptosis as both initiators (caspase-2, -8, -9, -10, 20, and -22) and executioners (caspase-3, -6, -7, and 21) [50,51]. Caspases are initially expressed as inactive procaspases that are activated by pro-apoptotic signals via proteolytic cleavage. Therefore, the effect of LOB3 on the proteolytic activation of caspases was examined in C6 cells. LOB3 activated both an apoptosis initiator, caspase-9, as well as an executioner, caspase-3, by promoting the proteolytic cleavage of these caspases at doses of 25 and 50 μM in C6 cells (Caspases are a family of endonucleases that act as critical links in the molecular networks that control apoptosis and play critical roles in the induction of apoptosis as both initiators (caspase-2, -8, -9, -10, 20, and -22) and executioners (caspase-3, -6, -7, and 21) [50][51]. Caspases are initially expressed as inactive procaspases that are activated by pro-apoptotic signals via proteolytic cleavage. Therefore, the effect of LOB3 on the proteolytic activation of caspases was examined in C6 cells. LOB3 activated both an apoptosis initiator, caspase-9, as well as an executioner, caspase-3, by promoting the proteolytic cleavage of these caspases at doses of 25 and 50 μM in C6 cells (

Figure 2D,F), indicating that LOB3 induces apoptosis of C6 cells by activating the apoptosis initiators and executioners. Moreover, similar to the semi-quantitative RT-PCR result (

Figure 2C,E), LOB3 markedly reduced the protein expression of the anti-apoptotic Bc1 family member, Bcl-2, at doses of 25 and 50 μM in C6 cells (

Figure 2D,F). Taken together, these results suggest that the cytotoxic effect of LOB3 on C6 cells is mediated by the induction of apoptosis through inhibiting the expression of anti-apoptotic genes, such as Bcl-2 and p53, as well as activating the proteolytic processing of both apoptosis initiator, caspase-9, and executioner, caspase-3.

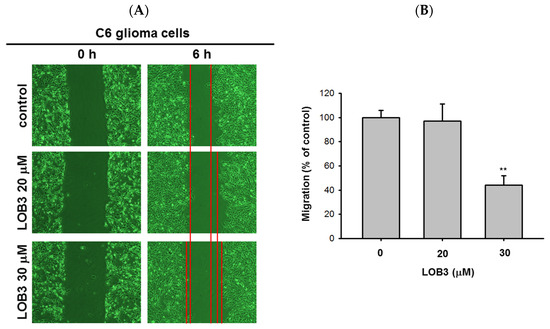

4. Anti-Migratory Effect of LOB3 in C6 Cells

Another fundamental feature of cancer is the migration of tumor cells from the original location where tumors arise to other parts of the body. It was reported that surfactin can reduce the 12-

O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA)-induced metastatic potentials, including invasion and migration of human breast carcinoma cells [52]. Therefore, the anti-migratory effect of LOB3 was evaluated in C6 cells. C6 cells treated with LOB3 (20 and 30 μM) were cultured for 6 h, and the degree of C6 cell migration was examined. Compared to the control, LOB3 markedly suppressed the migration of C6 cells at a dose of 30 μM (

Figure 3A,B). Interestingly, although LOB3 exerted a cytotoxic and anti-proliferative effect on C6 cells (

Figure 1B–D) by facilitating apoptosis at doses as low as 20 μM (

Figure 2), LOB3 did not suppress the migration of C6 cells at 20 μM, but 30 μM. This result indicates that the doses of LOB3 required to inhibit the proliferation and migration of C6 cells might not be same, since the molecules critical for cell proliferation and migration are different, and the inhibitory effect of LOB3 on the biological actions of these molecules might also be different in C6 cells. To identify the effective and optimal doses targeting both sets of these molecules and thereby inhibiting both the proliferation and migration of C6 cells, further molecular mechanism studies using various doses of LOB3 will be required. Taken together, these results suggest that LOB3 plays an anti-cancer role by not only inducing cytotoxicity but also suppressing the migration of C6 cells.

5. Conclusions

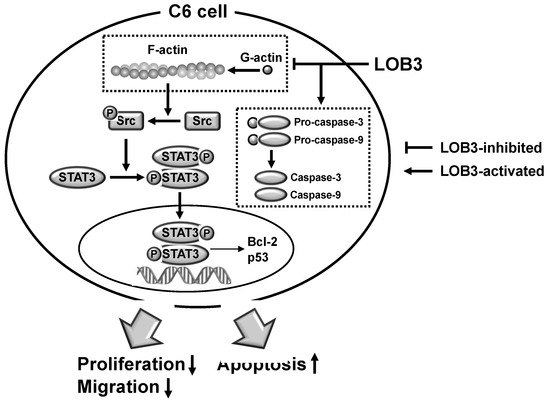

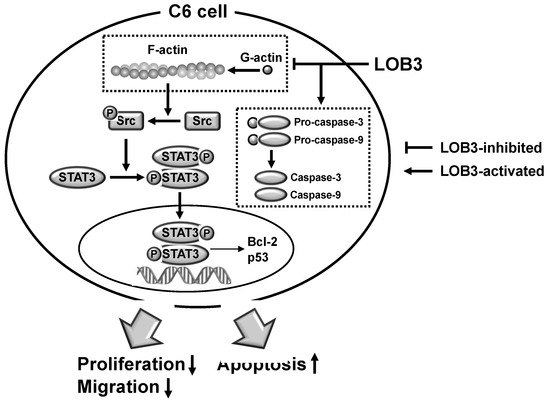

The current study investigated the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 and the underlying molecular mechanism in glioblastoma C6 cells. LOB3 induces the cytotoxicity of C6 cells by promoting apoptosis through modulating the expression of apoptosis-related genes and molecules. LOB3 also suppressed the motility of C6 cells, which is critical for cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis, by inhibiting actin polymerization, and LOB3 suppressed the activation of Src and STAT3, which are proto-oncogenic factors activated by actin polymerization in cancer cells. Despite these results, this study was limited to in vitro experiments using cancer cell lines, and further ex vivo studies using tumor cells from cancer animal models or human patients as well as in vivo studies using animal xenograft or orthotopic models are required to support and confirm the results of this study. In addition, the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 needs to be expanded to other types of cancers to confirm the general anti-cancer effect of LOB3 in a broad range of cancers. Moreover, the comparison studies for the anti-cancer effect of various LOs also need to be further investigated. In conclusion, LOB3 plays an anti-cancer role by facilitating the apoptotic death of C6 cells as well as inhibiting the migratory activity of C6 cells by modulating multiple factors associated with apoptosis, motility, cytoskeleton formation, and proto-oncogenic functions, as described in Figure 5. Given this evidence, this study proposes an anti-cancer role of a cyclic peptide, LOB3, which is present in flaxseed oil, in glioblastoma cells with a new understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms, which could provide insight into the development of effective and safer LO-based therapeutics to prevent and treat glioblastoma and even other types of cancers.

Figure 5. ThAnti-migratory effe pct of LOB3 in C6 cells. (A) Migratioposed modeln of C6 cells treated with the indicated doses of LOB3 for 6 h was analyzed under a light microscope. (B) Migrato illustrate theion areas (% of control) were calculated and plotted with Figure 3A. Stanti-cancetistical significance was analyzed by the Mann-Whitney U test. Result (A) is a r epresentactivitytive of three experiments. The data (B) are expressed as the means ± SD of LOB3three in experiments. ** p < 0.01 compared C6 cellto the vehicle-treated controls.

5. Conclusions

The current study investigated the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 and the underlying molecular mechanism in glioblastoma C6 cells. LOB3 induces the cytotoxicity of C6 cells by promoting apoptosis through modulating the expression of apoptosis-related genes and molecules. LOB3 also suppressed the motility of C6 cells, which is critical for cancer cell migration, invasion, and metastasis, by inhibiting actin polymerization, and LOB3 suppressed the activation of Src and STAT3, which are proto-oncogenic factors activated by actin polymerization in cancer cells. Despite these results, this study was limited to in vitro experiments using cancer cell lines, and further ex vivo studies using tumor cells from cancer animal models or human patients as well as in vivo studies using animal xenograft or orthotopic models are required to support and confirm the results of this study. In addition, the anti-cancer effect of LOB3 needs to be expanded to other types of cancers to confirm the general anti-cancer effect of LOB3 in a broad range of cancers. Moreover, the comparison studies for the anti-cancer effect of various LOs also need to be further investigated. In conclusion, LOB3 plays an anti-cancer role by facilitating the apoptotic death of C6 cells as well as inhibiting the migratory activity of C6 cells by modulating multiple factors associated with apoptosis, motility, cytoskeleton formation, and proto-oncogenic functions, as described in Figure 4. Given this evidence, this study proposes an anti-cancer role of a cyclic peptide, LOB3, which is present in flaxseed oil, in glioblastoma cells with a new understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms, which could provide insight into the development of effective and safer LO-based therapeutics to prevent and treat glioblastoma and even other types of cancers.

Figure 4. The proposed model to illustrate the anti-cancer activity of LOB3 in a C6 cell.

References

- Agnihotri, S.; Burrell, K.E.; Wolf, A.; Jalali, S.; Hawkins, C.; Rutka, J.T.; Zadeh, G. Glioblastoma, a brief review of history, molecular genetics, animal models and novel therapeutic strategies. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2013, 61, 25–41.

- Rock, K.; McArdle, O.; Forde, P.; Dunne, M.; Fitzpatrick, D.; O’Neill, B.; Faul, C. A clinical review of treatment outcomes in glioblastoma multiforme—The validation in a non-trial population of the results of a randomised Phase III clinical trial: Has a more radical approach improved survival? Br. J. Radiol. 2012, 85, e729–733.

- Grech, N.; Dalli, T.; Mizzi, S.; Meilak, L.; Calleja, N.; Zrinzo, A. Rising Incidence of Glioblastoma Multiforme in a Well-Defined Population. Cureus 2020, 12, e8195.

- Gallego, O. Nonsurgical treatment of recurrent glioblastoma. Curr. Oncol. 2015, 22, e273–281.

- Khosla, D. Concurrent therapy to enhance radiotherapeutic outcomes in glioblastoma. Ann. Transl. Med. 2016, 4, 54.

- Hirsch, S.; Roggia, C.; Biskup, S.; Bender, B.; Gepfner-Tuma, I.; Eckert, F.; Zips, D.; Malek, N.P.; Wilhelm, H.; Renovanz, M.; et al. Depatux-M and temozolomide in advanced high-grade glioma. Neuro Oncol. Adv. 2020, 2, vdaa063.

- Bahadur, S.; Sahu, A.K.; Baghel, P.; Saha, S. Current promising treatment strategy for glioblastoma multiform: A review. Oncol. Rev. 2019, 13, 417.

- Litak, J.; Mazurek, M.; Grochowski, C.; Kamieniak, P.; Rolinski, J. PD-L1/PD-1 Axis in Glioblastoma Multiforme. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5347.

- Caccese, M.; Indraccolo, S.; Zagonel, V.; Lombardi, G. PD-1/PD-L1 immune-checkpoint inhibitors in glioblastoma: A concise review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2019, 135, 128–134.

- Wang, X.; Guo, G.; Guan, H.; Yu, Y.; Lu, J.; Yu, J. Challenges and potential of PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy for glioblastoma. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2019, 38, 87.

- Parikh, M.; Maddaford, T.G.; Austria, J.A.; Aliani, M.; Netticadan, T.; Pierce, G.N. Dietary Flaxseed as a Strategy for Improving Human Health. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1171.

- Saleem, M.H.; Fahad, S.; Khan, S.U.; Din, M.; Ullah, A.; Sabagh, A.E.; Hossain, A.; Llanes, A.; Liu, L. Copper-induced oxidative stress, initiation of antioxidants and phytoremediation potential of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) seedlings grown under the mixing of two different soils of China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2020, 27, 5211–5221.

- Saleem, M.H.; Ali, S.; Hussain, S.; Kamran, M.; Chattha, M.S.; Ahmad, S.; Aqeel, M.; Rizwan, M.; Aljarba, N.H.; Alkahtani, S.; et al. Flax (Linum usitatissimum L.): A Potential Candidate for Phytoremediation? Biological and Economical Points of View. Plants 2020, 9, 496.

- Sharma, J.; Singh, R.; Goyal, P.K. Chemomodulatory Potential of Flaxseed Oil Against DMBA/Croton Oil-Induced Skin Carcinogenesis in Mice. Integr. Cancer Ther. 2016, 15, 358–367.

- Zhang, X.; Wang, H.; Yin, P.; Fan, H.; Sun, L.; Liu, Y. Flaxseed oil ameliorates alcoholic liver disease via anti-inflammation and modulating gut microbiota in mice. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 44.

- Zhu, H.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Tu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Wang, X.; Hou, Y.; Wang, C.; Chen, J.; Liu, Y. Flaxseed Oil Attenuates Intestinal Damage and Inflammation by Regulating Necroptosis and TLR4/NOD Signaling Pathways Following Lipopolysaccharide Challenge in a Piglet Model. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, e1700814.

- Bashir, S.; Sharma, Y.; Jairajpuri, D.; Rashid, F.; Nematullah, M.; Khan, F. Alteration of adipose tissue immune cell milieu towards the suppression of inflammation in high fat diet fed mice by flaxseed oil supplementation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0223070.

- De Silva, S.F.; Alcorn, J. Flaxseed Lignans as Important Dietary Polyphenols for Cancer Prevention and Treatment: Chemistry, Pharmacokinetics, and Molecular Targets. Pharmaceuticals 2019, 12, 68.

- Parikh, M.; Pierce, G.N. Dietary flaxseed: What we know and don’t know about its effects on cardiovascular disease. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 97, 75–81.

- Ratan, Z.A.; Jeong, D.; Sung, N.Y.; Shim, Y.Y.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Yi, Y.S.; Cho, J.Y. LOMIX, a Mixture of Flaxseed Linusorbs, Exerts Anti-Inflammatory Effects through Src and Syk in the NF-kappaB Pathway. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 859.

- Watanabe, Y.; Ohata, K.; Fukanoki, A.; Fujimoto, N.; Matsumoto, M.; Nessa, N.; Toba, H.; Kobara, M.; Nakata, T. Antihypertensive and Renoprotective Effects of Dietary Flaxseed and its Mechanism of Action in Deoxycorticosterone Acetate-Salt Hypertensive Rats. Pharmacology 2020, 105, 54–62.

- Zhu, L.; Sha, L.; Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Liu, P.; Dong, X.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. Dietary flaxseed oil rich in omega-3 suppresses severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus via anti-inflammation and modulating gut microbiota in rats. Lipids Health Dis. 2020, 19, 20.

- Saleem, M.H.; Kamran, M.; Zhou, Y.; Parveen, A.; Rehman, M.; Ahmar, S.; Malik, Z.; Mustafa, A.; Ahmad Anjum, R.M.; Wang, B.; et al. Appraising growth, oxidative stress and copper phytoextraction potential of flax (Linum usitatissimum L.) grown in soil differentially spiked with copper. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 257, 109994.

- Imran, M.; Sun, X.; Hussain, S.; Ali, U.; Rana, M.S.; Rasul, F.; Saleem, M.H.; Moussa, M.G.; Bhantana, P.; Afzal, J.; et al. Molybdenum-Induced Effects on Nitrogen Metabolism Enzymes and Elemental Profile of Winter Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Under Different Nitrogen Sources. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 2, 3009.

- Kajla, P.; Sharma, A.; Sood, D.R. Flaxseed-a potential functional food source. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 52, 1857–1871.

- Bruhl, L.; Matthaus, B.; Fehling, E.; Wiege, B.; Lehmann, B.; Luftmann, H.; Bergander, K.; Quiroga, K.; Scheipers, A.; Frank, O.; et al. Identification of bitter off-taste compounds in the stored cold pressed linseed oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 7864–7868.

- Burnett, P.G.; Jadhav, P.D.; Okinyo-Owiti, D.P.; Poth, A.G.; Reaney, M.J. Glycine-containing flaxseed orbitides. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 681–688.

- Burnett, P.G.; Olivia, C.M.; Okinyo-Owiti, D.P.; Reaney, M.J. Orbitide Composition of the Flax Core Collection (FCC). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 5197–5206.

- Okinyo-Owiti, D.P.; Dong, Q.; Ling, B.; Jadhav, P.D.; Bauer, R.; Maley, J.M.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Yang, J.; Sammynaiken, R. Evaluating the cytotoxicity of flaxseed orbitides for potential cancer treatment. Toxicol. Rep. 2015, 2, 1014–1018.

- Okinyo-Owiti, D.P.; Young, L.; Burnett, P.G.; Reaney, M.J. New flaxseed orbitides: Detection, sequencing, and (15)N incorporation. Biopolymers 2014, 102, 168–175.

- Sharav, O.; Shim, Y.Y.; Okinyo-Owiti, D.P.; Sammynaiken, R.; Reaney, M.J. Effect of cyclolinopeptides on the oxidative stability of flaxseed oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 88–96.

- Drygala, P.; Olejnik, J.; Mazur, A.; Kierus, K.; Jankowski, S.; Zimecki, M.; Zabrocki, J. Synthesis and immunosuppressive activity of cyclolinopeptide A analogues containing homophenylalanine. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 44, 3731–3738.

- Bell, A.; McSteen, P.M.; Cebrat, M.; Picur, B.; Siemion, I.Z. Antimalarial activity of cyclolinopeptide A and its analogues. Acta Pol. Pharm. 2000, 57, 134–136.

- Yang, J.; Jadhav, P.D.; Reaney, M.J.T.; Sammynaiken, R.; Yang, J. A novel formulation significantly increases the cytotoxicity of flaxseed orbitides (linusorbs) LOB3 and LOB2 towards human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Die Pharm. 2019, 74, 520–522.

- Shim, Y.Y.; Young, L.W.; Arnison, P.G.; Gilding, E.; Reaney, M.J. Proposed systematic nomenclature for orbitides. J. Nat. Prod. 2015, 78, 645–652.

- Zou, X.G.; Li, J.; Sun, P.L.; Fan, Y.W.; Yang, J.Y.; Deng, Z.Y. Orbitides isolated from flaxseed induce apoptosis against SGC-7901 adenocarcinoma cells. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 71, 929–939.

- Ostrom, Q.T.; Cioffi, G.; Gittleman, H.; Patil, N.; Waite, K.; Kruchko, C.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. CBTRUS Statistical Report: Primary Brain and Other Central Nervous System Tumors Diagnosed in the United States in 2012–2016. Neuro Oncol. 2019, 21, v1–v100.

- Heilos, D.; Rodriguez-Carrasco, Y.; Englinger, B.; Timelthaler, G.; van Schoonhoven, S.; Sulyok, M.; Boecker, S.; Sussmuth, R.D.; Heffeter, P.; Lemmens-Gruber, R.; et al. The Natural Fungal Metabolite Beauvericin Exerts Anticancer Activity In Vivo: A Pre-Clinical Pilot Study. Toxins 2017, 9, 258.

- Cao, X.H.; Wang, A.H.; Wang, C.L.; Mao, D.Z.; Lu, M.F.; Cui, Y.Q.; Jiao, R.Z. Surfactin induces apoptosis in human breast cancer MCF-7 cells through a ROS/JNK-mediated mitochondrial/caspase pathway. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010, 183, 357–362.

- Taniguchi, Y.; Yamamoto, N.; Hayashi, K.; Takeuchi, A.; Miwa, S.; Igarashi, K.; Higuchi, T.; Abe, K.; Yonezawa, H.; Araki, Y.; et al. Anti-tumor Effects of Cyclolinopeptide on Giant-cell Tumor of the Bone. Anticancer Res. 2019, 39, 6145–6153.

- Elmore, S. Apoptosis: A review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 2007, 35, 495–516.

- He, B.; Lu, N.; Zhou, Z. Cellular and nuclear degradation during apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2009, 21, 900–912.

- Wang, C.L.; Liu, C.; Niu, L.L.; Wang, L.R.; Hou, L.H.; Cao, X.H. Surfactin-induced apoptosis through ROS-ERS-Ca2+-ERK pathways in HepG2 cells. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2013, 67, 1433–1439.

- Saraste, A.; Pulkki, K. Morphologic and biochemical hallmarks of apoptosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 45, 528–537.

- Zhang, J.H.; Xu, M. DNA fragmentation in apoptosis. Cell Res. 2000, 10, 205–211.

- Belmokhtar, C.A.; Hillion, J.; Segal-Bendirdjian, E. Staurosporine induces apoptosis through both caspase-dependent and caspase-independent mechanisms. Oncogene 2001, 20, 3354–3362.

- Cornelissen, M.; Philippe, J.; De Sitter, S.; De Ridder, L. Annexin V expression in apoptotic peripheral blood lymphocytes: An electron microscopic evaluation. Apoptosis Int. J. Program. Cell Death 2002, 7, 41–47.

- Kale, J.; Osterlund, E.J.; Andrews, D.W. BCL-2 family proteins: Changing partners in the dance towards death. Cell Death Differ. 2018, 25, 65–80.

- Janicke, R.U.; Sohn, D.; Schulze-Osthoff, K. The dark side of a tumor suppressor: Anti-apoptotic p53. Cell Death Differ. 2008, 15, 959–976.

- Espinosa-Oliva, A.M.; Garcia-Revilla, J.; Alonso-Bellido, I.M.; Burguillos, M.A. Brainiac Caspases: Beyond the Wall of Apoptosis. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 500.

- McIlwain, D.R.; Berger, T.; Mak, T.W. Caspase functions in cell death and disease. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2015, 7, a026716.

- Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, Y.J.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, Y. Surfactin suppresses TPA-induced breast cancer cell invasion through the inhibition of MMP-9 expression. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 42, 287–296.