Silkworm is an economically important insect that synthetizes silk proteins for silk production in silk gland, and silk gland cells undergo endoreplication during larval period. Transcription factor Myc is essential for cell growth and proliferation. Although silkworm Myc gene has been identified previously, its biological functions in silkworm silk gland are still largely unknown. In this study, we examined whether enhanced Myc expression in silk gland could facilitate cell growth and silk production. Based on a transgenic approach, Myc was driven by the promoter of the fibroin heavy chain (FibH) gene to be successfully overexpressed in posterior silk gland. Enhanced Myc expression in the PSG elevated FibH expression by about 20% compared to the control, and also increased the weight and shell rate of the cocoon shell.

- silkworm

- silk gland

- Myc overexpression

- DNA replication

- silk production

1. Introduction

The silkworm (

Bombyx mori) is an economically important insect that synthesizes silk proteins for silk production in the silk gland. The silk gland comprises three parts, namely, anterior (ASG), middle (MSG), and posterior (PSG). Cell numbers in the silk gland are determined by mitosis during the late embryonic stage [1]. During the larval stage, silk gland cells stop the mitotic cell cycle and enter into endoreplication. After approximately 17–19 rounds of endoreplicating cell cycles, also called the endocycle, the DNA content in each cell can be increased by about 400,000 times, which results in a dendritic nucleus [2,3,4].

) is an economically important insect that synthesizes silk proteins for silk production in the silk gland. The silk gland comprises three parts, namely, anterior (ASG), middle (MSG), and posterior (PSG). Cell numbers in the silk gland are determined by mitosis during the late embryonic stage [1]. During the larval stage, silk gland cells stop the mitotic cell cycle and enter into endoreplication. After approximately 17–19 rounds of endoreplicating cell cycles, also called the endocycle, the DNA content in each cell can be increased by about 400,000 times, which results in a dendritic nucleus [2][3][4].

As is well known, endoreplicating cells generally undergo multiple rounds of genome DNA replication without cell mitosis or chromosome segregation, leading to a giant cell nucleus [5,6]. Numerous studies demonstrated that both the transition of mitosis-to-endocycle and oscillation of DNA replication during the endoreplication process are determined by an upregulated expression of a scaffold protein Fzr [6,7]. Previous studies in

As is well known, endoreplicating cells generally undergo multiple rounds of genome DNA replication without cell mitosis or chromosome segregation, leading to a giant cell nucleus [5][6]. Numerous studies demonstrated that both the transition of mitosis-to-endocycle and oscillation of DNA replication during the endoreplication process are determined by an upregulated expression of a scaffold protein Fzr [6][7]. Previous studies in

Drosophila salivary gland and ovary, two tissues with an endoreplicating cell cycle, reveal that blocking Fzr expression results in an arrest of DNA replication and the failure of mitotic-to-endocycle transition [8,9,10]. Notably, the initiation of DNA replication depends on the assembling of the pre-replication complex (preRC) on the origin of DNA replication [11,12]. The mini-chromosome maintenance proteins 2–7 (MCM2-7), which are identified as preRC subunits, form a hexameric complex during the G1 phase and functions as a DNA helicase to unwind genomic DNA bidirectionally during the S phase; then, they initiate DNA replication [12,13,14]. In silkworm silk gland, oncogene

salivary gland and ovary, two tissues with an endoreplicating cell cycle, reveal that blocking Fzr expression results in an arrest of DNA replication and the failure of mitotic-to-endocycle transition [8][9][10]. Notably, the initiation of DNA replication depends on the assembling of the pre-replication complex (preRC) on the origin of DNA replication [11][12]. The mini-chromosome maintenance proteins 2–7 (MCM2-7), which are identified as preRC subunits, form a hexameric complex during the G1 phase and functions as a DNA helicase to unwind genomic DNA bidirectionally during the S phase; then, they initiate DNA replication [12][13][14]. In silkworm silk gland, oncogene

Ras1(CA), insulin, and ecdysone have been shown to be involved in DNA replication [15,16,17]. Undoubtedly, decoding endoreplication of silk gland cells should be helpful for better understanding silk gland growth and silk protein synthesis. Actually, PSG-specific overexpression of some growth-related regulators, such as

, insulin, and ecdysone have been shown to be involved in DNA replication [15][16][17]. Undoubtedly, decoding endoreplication of silk gland cells should be helpful for better understanding silk gland growth and silk protein synthesis. Actually, PSG-specific overexpression of some growth-related regulators, such as

Ras

and

Yorkie, can elevate silk protein genes transcription and silk production by promoting endoreplication progression and increasing DNA content in the PSG cells [15,18]. On the contrary, PSG-specific knockout of the

, can elevate silk protein genes transcription and silk production by promoting endoreplication progression and increasing DNA content in the PSG cells [15][18]. On the contrary, PSG-specific knockout of the

LaminA/C

gene, which is involved in maintaining the chromatin structure, causes a decrease in DNA content, silk protein gene transcriptions, and silk production [19].

Transcription factor Myc has been primarily identified as an oncogene in mammalian tumor cells and belongs to leucine zipper transcription factor family [20]. Previous reports in animals and plants have demonstrated that Myc is involved in regulating multiple physiological processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation [21,22], cell growth [23], and cell self-renewal [24,25]. Enhanced

Transcription factor Myc has been primarily identified as an oncogene in mammalian tumor cells and belongs to leucine zipper transcription factor family [20]. Previous reports in animals and plants have demonstrated that Myc is involved in regulating multiple physiological processes, such as cell proliferation and differentiation [21][22], cell growth [23], and cell self-renewal [24][25]. Enhanced

Myc

expression promotes tumorigenesis, while

Myc deletion strongly inhibits cell activity and leads to proliferative arrest [22,26]. Increasing evidence demonstrated that Myc is involved in cell-cycle progression mainly by the initiating DNA replication and G1-S phase transition [27,28]. The observation in

deletion strongly inhibits cell activity and leads to proliferative arrest [22][26]. Increasing evidence demonstrated that Myc is involved in cell-cycle progression mainly by the initiating DNA replication and G1-S phase transition [27][28]. The observation in

Drosophila

salivary gland reveals that

Myc

heterozygous mutation induces continuous segregation of mitotic cells and prevents the entrance of endoreplication progression [29].

Previous reports in silkworm have demonstrated that silencing

Myc expression in ovary-derived BmN4 cells causes an arrest in cell-cycle progression, and Myc is also involved in ecdysteroid regulation of cell-cycle progression in wing disc [30,31]. However, the function of Myc in silkworm silk gland with endoreplicating cell cycle remains unclear. In the present study, based on a transgenic approach, we used the promoter of the PSG-specific

expression in ovary-derived BmN4 cells causes an arrest in cell-cycle progression, and Myc is also involved in ecdysteroid regulation of cell-cycle progression in wing disc [30][31]. However, the function of Myc in silkworm silk gland with endoreplicating cell cycle remains unclear. In the present study, based on a transgenic approach, we used the promoter of the PSG-specific

FibH

gene to drive

Myc

overexpression in the PSG. PSG-specific overexpression of the

Myc

gene not only increased the size and DNA content of PSG cells but also elevated the weight and shell rate of cocoon. Mechanistically, in addition to silk protein gene

FibH

,

Myc

overexpression also upregulated the transcription of the

MCM

genes that are involved in DNA replication. These data suggest that enhanced

Myc

expression in silkworm silk gland promotes DNA replication and silk production.

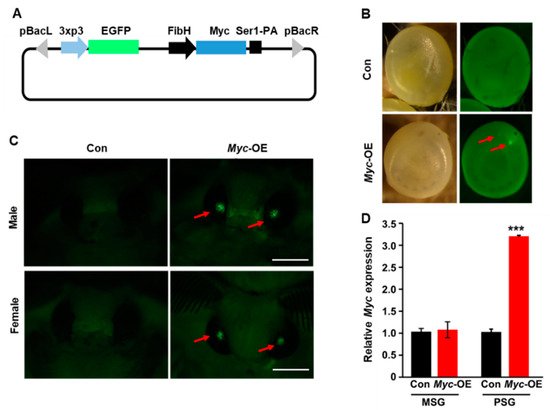

2. Construction of Transgenic Silkworm with PSG-Specific Myc Overexpression

To understand the roles of the

Myc

gene in both silk gland development and silk production, we first constructed transgenic silkworm with PSG-specific

Myc

overexpression. Based on the full-length sequence of silkworm

Myc

gene, we cloned the opening reading frame of the

Myc

gene and constructed recombinant

Myc

overexpression plasmid driven by

FibH

promoter, which is specifically activated in the PSG (

A). In total, 90 non-diapause D9L embryos were microinjected with the

FibH

-

Myc

recombinant plasmid, and 72 embryos were allowed to survive to develop to adults. EGFP-positive eggs in G1 generation were screened as positive transgenic strains (

B,C) and the positive rate was about 5%. Besides, the PSG of transgenic silkworm was isolated to determine whether

Myc

was specifically overexpressed in the PSG. RT-qPCR analysis confirmed that compared to the control,

Myc

was highly expressed in the PSG of transgenic silkworm (

D). These results indicate that

Myc

was specifically overexpressed in the PSG of transgenic silkworm.

Figure 1. Generation of transgenic silkworm with PSG-specific Myc overexpression. (A) Schematic illustration of the vector for Myc overexpression driven by the FibH promoter. (B,C) EGFP-positive eggs (B) and adults (C) were screened in G1 generation. (D) Myc was highly expressed in the PSG of transgenic silkworm. Values are represented as means ± S.E. (error bars). For the significance test: *** p < 0.001 vs. the control.

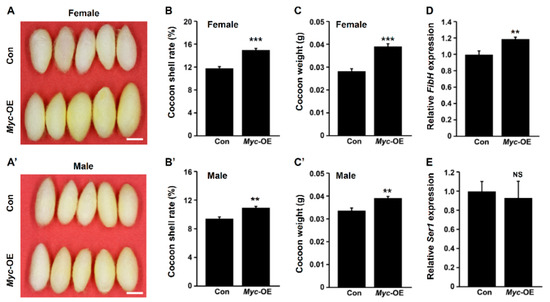

3. PSG-Specific Myc Overexpression Improves Silk Yield

We next investigated the effects of PSG-specific

Myc

overexpression on silk yield. The results showed that the cocoons of female transgenic silkworm individuals with PSG-specific

Myc

overexpression were obviously bigger than that of wild-type silkworm, and the cocoons of male silkworm increased by a small amount compared to the wild-type silkworm (

A,A’). The cocoon shell rates were elevated by 25% and 22% in female and male transgenic silkworms, respectively (

B,B’). Further statistics analysis revealed that compared to the control,

Myc

overexpression led to an increase in the weight of cocoon shell (

C,C’). Moreover, the transcription of silk protein gene

FibH

increased by about 20% following

Myc

overexpression (

D), but

Myc

overexpression did not affect the transcriptions of PSG-specific fibroin light chain (

FibL

) and

P25

genes (

) as well as MSG-specific sericin 1 (

Ser1

) gene (

E). These data suggest that

Myc

overexpression in the PSG improves silk yield.

Figure 2.

Enhanced

Myc

expression in the PSG elevates silk yield. (

A

,

A

’) Cocoon size of female (

A

) and male (

A

’) transgenic silkworms with

Myc

overexpression increased compared with control. Scale bar, 1 cm. (

B

,

C

’) The cocoon shell rates (

B

,

B

’) and cocoon weight (

C

,

C

’) were both largely increased following PSG-specific

Myc

overexpression. (

D

,

E

)

Myc

overexpression in the PSG promoted the transcription of

FibH

(

D

) but had no effect on the transcription of

Ser1

(

E

). Values are represented as means ± S.E. (error bars). For the significance test: **

p

< 0.01, ***

p

< 0.001 vs. the control.

4. Discussion

Silkworm is an economically important insect that produces silk fiber and silk proteins that are synthesized by the silk gland in which the cells undergo endoreplication. It has been demonstrated that the overexpression of

Ras1(CA)

and

Yorkie in the silk gland improved silk yield by promoting DNA replication and increasing protein synthesis [15,18], while PSG-specific knockout of

in the silk gland improved silk yield by promoting DNA replication and increasing protein synthesis [15][18], while PSG-specific knockout of

LaminA/C causes a decrease in DNA content, silk protein gene transcription, and silk yield [19]. DNA replication in silk gland cells can also be regulated by ecdysone and insulin [16,17]. Intriguingly, previous studies reported that ecdysone mediated DNA replication and cell proliferation in silkworm wing disc cells by positively regulated

causes a decrease in DNA content, silk protein gene transcription, and silk yield [19]. DNA replication in silk gland cells can also be regulated by ecdysone and insulin [16][17]. Intriguingly, previous studies reported that ecdysone mediated DNA replication and cell proliferation in silkworm wing disc cells by positively regulated

Myc

transcription, and Myc is required for DNA replication and tissue growth in

Drosophila endoreplicating tissues [10,29,30,33]. Accordingly, we here conducted a transgenic overexpression of the

endoreplicating tissues [10][29][30][32]. Accordingly, we here conducted a transgenic overexpression of the

Myc

gene in the PSG and observed that enhanced

Myc

expression promotes DNA replication and silk protein synthesis. These data indicate that Myc plays conserved roles in regulating DNA replication and protein synthesis in different types of endoreplicating cells.

The members of the MCM family, MCM2-MCM7, interacted physically to form a hexameric complex and colocalized at assembled replication origins to initiate DNA synthesis in endoreplicating cells [12,13,14]. This hexameric helicase complex is essential for DNA replication by providing a platform for recruitment of other preRC subunits and bidirectionally unwinding genomic DNA [34,35]. Our previous study found that

The members of the MCM family, MCM2-MCM7, interacted physically to form a hexameric complex and colocalized at assembled replication origins to initiate DNA synthesis in endoreplicating cells [12][13][14]. This hexameric helicase complex is essential for DNA replication by providing a platform for recruitment of other preRC subunits and bidirectionally unwinding genomic DNA [33][34]. Our previous study found that

Drosophila

Myc positively regulated the transcription of the

MCM6

gene by directly binding to a specific motif within its promoter during endoreplication [10]. We here observed that

Myc

overexpression in silkworm PSG can upregulate the transcription of three members of the MCM family,

MCM5

,

MCM6

, and

MCM7

, which is most likely correlated with an increase in DNA content following

Myc

overexpression. Whether Myc can directly bind to the promoter of silkworm

MCM

genes needs further investigation.

High expression of silk proteins in silkworm silk gland is required for silk production. We found that enhanced

Myc

expression in the PSG elevates both the transcription of silk protein gene

FibH

and silk production. This elevation may be associated with a

Myc

overexpression-caused increase in DNA content. In addition, the transcription of the

FibH

gene can be regulated by other silk gland-specific transcription by its direct binding to the

FibH promoter, including basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Sage [36], nuclear hormone receptor FTZ-F1 [37], and fibroin modulator binding protein-1 [38]. It should be necessary for elucidating whether Myc can directly regulate the transcription of silk protein genes.

promoter, including basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Sage [35], nuclear hormone receptor FTZ-F1 [36], and fibroin modulator binding protein-1 [37]. It should be necessary for elucidating whether Myc can directly regulate the transcription of silk protein genes.

References

- Perdrix-Gillot, S. DNA synthesis and endomitoses in the giant nuclei of the silkgland of Bombyx mori. Biochimie 1979, 61, 171–204.

- Henderson, S.C.; Locke, M. The development of branched silk gland nuclei. Tissue Cell 1991, 23, 867–880.

- Niranjanakumari, S.; Gopinathan, K.P. DNA polymerase Delta from the silk glands of Bombyx mori. J. Biol. Chem. 1992, 267, 17531–17539.

- Dhawan, S.; Gopinathan, K.P. Cell cycle events during the development of the silk glands in the mulberry silkworm Bombyx mori. Dev. Genes Evol. 2003, 213, 435–444.

- Edgar, B.A.; Zielke, N.; Gutierrez, C. Endocycles: A recurrent evolutionary innovation for post-mitotic cell growth. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2014, 15, 197–210.

- Zielke, N.; Edgar, B.A.; De Pamphilis, M.L. Endoreplication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2013, 5, a012948.

- Sigrist, S.J.; Lehner, C.F. Drosophila fizzy-related down-regulates mitotic cyclins and is required for cell proliferation arrest and entry into endocycles. Cell 1997, 90, 671–681.

- Schaeffer, V.; Althauser, C.; Shcherbata, H.R.; Deng, W.M.; Ruohola-Baker, H. Notch-dependent Fizzy-related/Hec1/Cdh1 expression is required for the mitotic-to-endocycle transition in Drosophila follicle cells. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, 630–636.

- Shcherbata, H.R.; Althauser, C.; Findley, S.D.; Ruohola-Baker, H. The mitotic-to-endocycle switch in Drosophila follicle cells is executed by Notch-dependent regulation of G1/S, G2/M and M/G1 cell-cycle transitions. Development 2004, 131, 3169–3181.

- Qian, W.; Li, Z.; Song, W.; Zhao, T.; Wang, W.; Peng, J.; Wei, L.; Xia, Q.; Cheng, D. A novel transcriptional cascade is involved in Fzr-mediated endoreplication. Nucl. Acids Res. 2020, 48, 4214–4229.

- Blow, J.J.; Dutta, A. Preventing re-replication of chromosomal DNA. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 6, 476–486.

- Costa, A.; Hood, I.V.; Berger, J.M. Mechanisms for initiating cellular DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2013, 82, 25–54.

- Pacek, M.; Tutter, A.V.; Kubota, Y.; Takisawa, H.; Walter, J.C. Localization of MCM2-7, Cdc45, and GINS to the site of DNA unwinding during eukaryotic DNA replication. Mol. Cell 2006, 21, 581–587.

- Eward, K.L.; Obermann, E.C.; Shreeram, S.; Loddo, M.; Fanshawe, T.; Williams, C.; Jung, H.I.; Prevost, A.T.; Blow, J.J.; Stoeber, K.; et al. DNA replication licensing in somatic and germ cells. J. Cell Sci. 2004, 117, 5875–5886.

- Ma, L.; Xu, H.; Zhu, J.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, R.J.; Xia, Q.; Li, S. Ras1(CA) overexpression in the posterior silk gland improves silk yield. Cell Res. 2011, 21, 934–943.

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Tang, X.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, P.; Pan, M.; Lu, C. DNA synthesis during endomitosis is stimulated by insulin via the PI3K/Akt and TOR signaling pathways in the silk gland cells of Bombyx mori. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 6266–6280.

- Li, Y.F.; Chen, X.Y.; Zhang, C.D.; Tang, X.F.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.H.; Pan, M.H.; Lu, C. Effects of starvation and hormones on DNA synthesis in silk gland cells of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Insect Sci. 2016, 23, 569–578.

- Zhang, P.; Liu, S.; Song, H.S.; Zhang, G.; Jia, Q.; Li, S. Yorkie (CA) overexpression in the posterior silk gland improves silk yield in Bombyx mori. J. Insect Physiol. 2017, 100, 93–99.

- Liu, Y.; Ma, S.; Chang, J.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Shi, R.; Zhang, J.; Lu, W.; Liu, Y.; Xia, Q. Tissue-specific genome editing of laminA/C in the posterior silk glands of Bombyx mori. J. Genet. Genom. 2017, 44, 451–459.

- Roussel, M.; Saule, S.; Lagrou, C.; Rommens, C.; Beug, H.; Graf, T.; Stehelin, D. Three new types of viral oncogene of cellular origin specific for haematopoietic cell transformation. Nature 1979, 281, 452–455.

- Fulco, C.P.; Munschauer, M.; Anyoha, R.; Munson, G.; Grossman, S.R.; Perez, E.M.; Kane, M.; Cleary, B.; Lander, E.S.; Engreitz, J.M. Systematic mapping of functional enhancer-promoter connections with CRISPR interference. Science 2016, 354, 769–773.

- Scognamiglio, R.; Cabezas-Wallscheid, N.; Thier, M.C.; Altamura, S.; Reyes, A.; Prendergast, A.M.; Baumgartner, D.; Carnevalli, L.S.; Atzberger, A.; Haas, S.; et al. Myc depletion induces a pluripotent dormant state mimicking diapause. Cell 2016, 164, 668–680.

- Fan, L.; Peng, G.; Sahgal, N.; Fazli, L.; Gleave, M.; Zhang, Y.; Hussain, A.; Qi, J. Regulation of c-Myc expression by the histone demethylase JMJD1A is essential for prostate cancer cell growth and survival. Oncogene 2016, 35, 2441–2452.

- Kanatsu-Shinohara, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ogonuki, N.; Ogura, A.; Morimoto, H.; Cheng, P.F.; Eisenman, R.N.; Trumpp, A.; Shinohara, T. Myc/Mycn-mediated glycolysis enhances mouse spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 2637–2648.

- Zheng, H.; Ying, H.; Yan, H.; Kimmelman, A.C.; Hiller, D.J.; Chen, A.J.; Perry, S.R.; Tonon, G.; Chu, G.C.; Ding, Z.; et al. Pten and p53 converge on c-Myc to control differentiation, self-renewal, and transformation of normal and neoplastic stem cells in glioblastoma. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 2008, 73, 427–437.

- Adhikary, S.; Eilers, M. Transcriptional regulation and transformation by Myc proteins. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005, 6, 635–645.

- Dominguez-Sola, D.; Gautier, J. MYC and the control of DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2014, 4, a014423.

- Dominguez-Sola, D.; Ying, C.Y.; Grandori, C.; Ruggiero, L.; Chen, B.; Li, M.; Galloway, D.A.; Gu, W.; Gautier, J.; Dalla-Favera, R. Non-transcriptional control of DNA replication by c-Myc. Nature 2007, 448, 445–451.

- Maines, J.Z.; Stevens, L.M.; Tong, X.; Stein, D. Drosophila dMyc is required for ovary cell growth and endoreplication. Development 2004, 131, 775–786.

- Moriyama, M.; Osanai, K.; Ohyoshi, T.; Wang, H.B.; Iwanaga, M.; Kawasaki, H. Ecdysteroid promotes cell cycle progression in the Bombyx wing disc through activation of c-Myc. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2016, 70, 1–9.

- Mon, H.; Li, Z.; Kobayashi, I.; Tomita, S.; Lee, J.; Sezutsu, H.; Tamura, T.; Kusakabe, T. Soaking RNAi in Bombyx mori BmN4-SID1 cells arrests cell cycle progression. J. Insect Sci. 2013, 13, 155.

- Pierce, S.B.; Yost, C.; Britton, J.S.; Loo, L.W.; Flynn, E.M.; Edgar, B.A.; Eisenman, R.N. dMyc is required for larval growth and endoreplication in Drosophila. Development 2004, 131, 2317–2327.

- Frigola, J.; He, J.; Kinkelin, K.; Pye, V.E.; Renault, L.; Douglas, M.E.; Remus, D.; Cherepanov, P.; Costa, A.; Diffley, J.F.X. Cdt1 stabilizes an open MCM ring for helicase loading. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 15720.

- Fernandez-Cid, A.; Riera, A.; Tognetti, S.; Herrera, M.C.; Samel, S.; Evrin, C.; Winkler, C.; Gardenal, E.; Uhle, S.; Speck, C. An ORC/Cdc6/MCM2-7 complex is formed in a multistep reaction to serve as a platform for MCM double-hexamer assembly. Mol. Cell 2013, 50, 577–588.

- Zhao, X.M.; Liu, C.; Li, Q.Y.; Hu, W.B.; Zhou, M.T.; Nie, H.Y.; Zhang, Y.X.; Peng, Z.C.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q.Y. Basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor Bmsage is involved in regulation of fibroin H-chain gene via interaction with SGF1 in Bombyx mori. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e94091.

- Zhou, C.; Zha, X.; Shi, P.; Zhao, P.; Wang, H.; Zheng, R.; Xia, Q. Nuclear hormone receptor BmFTZ-F1 is involved in regulating the fibroin heavy chain gene in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2016, 1860, 2529–2536.

- Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, P.; Liu, C.; Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhao, P.; Xia, Q.; He, H. Insights into the repression of fibroin modulator binding protein-1 on the transcription of fibroin H-chain during molting in Bombyx mori. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2019, 104, 39–49.