HIV-1 (human immunodeficiency virus type 1) infection begins with the attachment of the virion to a host cell by its envelope glycoprotein (Env), which subsequently induces fusion of viral and cell membranes to allow viral entry. Upon binding to primary receptor CD4 and coreceptor (e.g., chemokine receptor CCR5 or CXCR4), Env undergoes large conformational changes and unleashes its fusogenic potential to drive the membrane fusion.

- HIV

- envelope glycoprotein

- viral entry

- membrane fusion

1. HIV-1 Entry

The strategy that enveloped viruses, such as HIV-1 (human immunodeficiency virus type 1), use to gain entry into their host cells is membrane fusion, which is an energetically favorable process but with high kinetic barriers [1][2]. Virus-encoded fusion proteins are catalysts and undergo structural rearrangements from a high-energy, metastable prefusion conformation to a low-energy, stable postfusion conformation, providing free energy for overcoming these kinetic barriers [3][4][5]. In the case of HIV-1, its envelope glycoprotein (Env) functions as the fusion protein. The Env protein is synthesized as a precursor, gp160 (for glycoprotein with an apparent molecular weight of 160 kDa;

3

3. It is generally believed that sequential binding of gp120 to primary receptor CD4 and coreceptor (e.g., chemokine receptor CCR5 or CXCR4) initiates a cascade of refolding events in gp41 that drive the membrane fusion process [7][8]. The mature Env spikes are also the sole antigens on the surface of virion and induce strong immune responses in infected individuals [9][10]. Not surprisingly, HIV-1 Env is a critical target for the development of both vaccines and therapeutics against the virus. Recent advances in the structural biology of HIV-1 Env and its complexes with the host receptors, as well as in the design of novel fusion inhibitors, have provided new insights into HIV-1 entry and its inhibition. In this review, we summarize our latest understanding of the membrane fusion catalyzed by HIV-1 Env and discuss related therapeutic strategies to block viral entry.

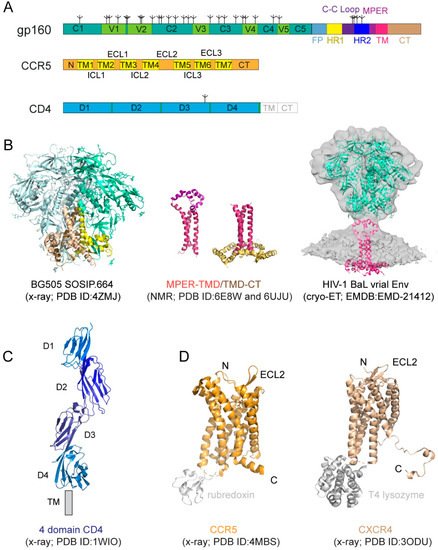

Figure 1.

A

B

C

D

C

2. Structures of HIV-1 Env and Cellular Receptors

2.1. HIV-1 Env

Figure 1A). The protein has been historically a very challenging target for structural analysis due to technical difficulties associated with large membrane-bound glycoproteins. Nevertheless, a truncated version of gp120, named ‘gp120 core’, with V1-V3 and terminal segments deleted, was crystallized in two forms: a deglycosylated one in complex with CD4 and a CD4-induced antibody for HIV-1 [17] and an unliganded and fully glycosylated one for closely related simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) [18], producing structures that gave us the first glimpse of gp120 folding and its interaction with CD4. Likewise, the structure of a gp41 fragment of HR1 and HR2 has been solved by X-ray crystallography and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) [7][8][19][20][21], revealing the postfusion conformation of gp41 as a six-helix bundle, in which the HR1 and HR2 helices are arranged into a trimer of hairpins.

The first breakthrough on high-resolution structures of the Env trimer only came more than a decade later from a designed soluble construct, termed ‘SOSIP’, with stabilizing modifications (i.e., a disulfide bond between gp120 and gp41, an I559P substitution in gp41, and a truncation at residue 664 deleting the MPER; [22]) by both cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography [23][24][25] (

Figure 1B). Subsequently, the structure of a detergent-solubilized Env trimer without the CT and SOSIP modifications was determined in complex with neutralizing antibodies by cryo-EM [26]. More recently, the cryo-EM structures of two full-length HIV-1 Env constructs purified in detergent have also been reported [27][28]. These trimer structures have shown that the prefusion gp41 adopts a drastically different conformation from the postfusion six-helix bundle structure and provided much-needed insights on Env structure and its conformational changes. The MPER, TMD, and CT are all disordered in these structures, however, highlighting the important role of the lipid bilayer in stabilizing the structure of these regions. An attempt to determine the structure of the missing regions using a full-length Env reconstituted in lipid nanodiscs did not yield much additional high-resolution information [29]. In addition, cryo-electron tomography (cryo-ET) has been used to study the structures of Env trimer on the surface of both HIV and SIV chemically inactivated virions, leading to reconstructions at a low resolution (~20 Å) during early days [30][31][32][33], and a more recent one at ~10Å resolution (

Recent data indicate that the membrane-related components of HIV-1 Env, including the MPER, TM domain (TMD), and CT, influence the stability and antigenicity of the Env ectodomain, as well as cell–cell fusion and viral infection [12][35][36][37][38][39], in agreement with their conserved features. For example, the MPER has been studied extensively because it contains epitopes recognized by a group of broadly neutralizing antibodies [40][41][42][43][44]. The TMD has a ‘GXXXG’ motif and a highly conserved positively charged residue (Lys or Arg). The CT includes the Kennedy sequence, three conserved amphipathic α-helices segments referred to as a lentiviral lytic peptide (LLPs: LLP1, LLP2, and LLP3) [45][46][47]. Truncation of the CT of the full-length HIV-1 Envs has minimal impact on their fusogenic activity, but it has an unexpectedly large impact on the antigenic structure of the ectodomain [35]. Some other studies showed that the CT modifications had little effect on the Env antigenicity for certain HIV-1 isolates [48][49][50]. Nevertheless, structural studies in the context of a lipid bilayer appear to support crosstalk between the CT and the ectodomain.

Figure 1B). The TMD forms a well-ordered trimer, and that mutational changes disrupting the TMD trimer alter antibody sensitivity of the ectodomain, suggesting that the TMD contributes to Env stability and antigenicity. Moreover, although previous studies reported that the MPER might be buried in the viral membrane [52][53][54], the NMR structure that contains both the MPER and TMD in the bicelle system has shown that the MPER forms a well-ordered trimeric assembly, not buried in the membrane [12] (

2.2. Primary Receptor CD4

Figure 1A), exposed on the cell surface. It was shown to be the primary HIV-1 receptor shortly after the discovery of the HIV virus [55][56][57]. The structure of CD4 alone or in complex with gp120 core has been determined by X-ray crystallography [14][17][58][59][60] (

2.3. Coreceptor

CD4 alone was not sufficient to support HIV-1 infection, leading to intensive search and subsequent identification of CXCR4 and CCR5, the seven-transmembrane (7TM) chemokine receptors, as the coreceptor for the virus [61][62][63][64][65][66]. Coreceptor usage is the primary determinant for viral tropism [67], as those that use CCR5 (R5 viruses) are the dominant form during viral transmission, and others using CXCR4 (X4 viruses) or both (dual-tropic; R5/X4 viruses) emerge mainly during disease progression [68][69][70][71]. Both CCR5 and CXCR4 have a core structure formed by 7TM helices, decorated by an N-terminal segment and three extracellular loops (ECL) exposed outside of the cell, as well as three intracellular loops (ICL), and a cytoplasmic C-terminal tail on the opposite side of the membrane (

Figure 1A). A C-terminally truncated CXCR4 construct with stabilizing mutations, and a T4 lysozyme fusion in complex with different ligands, and a similarly modified CCR5 construct containing a rubredoxin fusion in complex with the anti-HIV drug, Maraviroc, have been crystallized, yielding high-resolution structures [15][16][72] (

Figure 1C; [73]). A two-site model has been proposed for their ligand interactions [74], as the N-terminal segment of CXCR4 or CCR5 forms the chemokine recognition site 1 (CRS1) to bind the globular core domain of chemokine, while their TM helices make up the chemokine recognition site 2 (CRS2) to interact with the N-terminus of the chemokine. These structures have revealed the general architecture of these chemokine receptors and their interactions with the ligands [15][16][72][75], but they did not provide many of the molecular details of how they function as HIV-1 coreceptors.

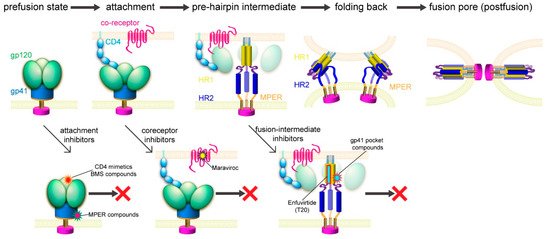

3. Molecular Mechanism of HIV-1 Membrane Fusion

3.1. Interactions between HIV-1 Env and Cellular Receptors

3.1.1. Interactions between Env and CD4

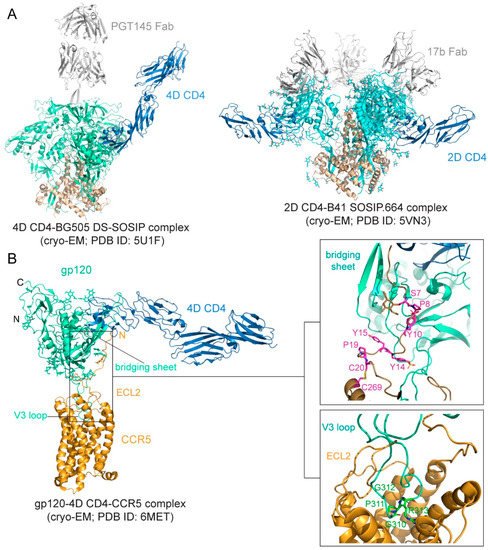

The binding affinity is in the low nM range for soluble CD4 and monomeric gp120 [76][77][78], but it can be ~20 nM for various trimeric forms of soluble Env trimers [78][79]. The binding interface between CD4 and gp120 was first defined in the structure of the gp120 core-CD4 complex [17]. Gp120 core has two separate domains—inner domain and outer domain, and there is also a four-strand β-sheet, named bridging sheet, between the two domains. CD4 interacts with gp120 mainly at the interface between the inner domain and outer domain, inducing the formation of the bridging sheet. The structures of CD4 in complex with Env trimer have been determined using the SOSIP trimer as well. The CD4 bound trimer adopts a more open conformation compared with the unliganded Env SOSIP trimer (

Figure 2A). The Env conformational changes include V1–V2 flip, V3 exposure, the bridging sheet formation, and repositioning of the fusion peptide in gp41 [80][81]. Another further constrained trimer, named DS-SOSIP.664, was created by introducing a disulfide bond (201C–433C) into the SOSIP [11]. This trimer binds sCD4 with an asymmetric 1:1 (CD4:trimer) stoichiometry. It appears that a single CD4 molecule is embraced by a quaternary HIV-1 Env surface with the previous defined CD4-binding region in the outer domain of one gp120 protomer and with the second CD4-binding site (CD4-BS2) in the inner domain of a neighboring gp120 protomer (

Figure 2.

A

B

3.1.2. Interactions between Env and Coreceptor

Preparing stable and homogenous samples of purified CCR5 or CXCR4 has been technically challenging, and various assays have, therefore, been employed to measure the binding affinity for the Env-coreceptor interactions in the presence of soluble CD4 (<10 nM for CCR5; 200–500 nM for CXCR4; [84][85][86][87]). The first structure of a full-length monomeric gp120 in complex with a soluble 4D-CD4 and an unmodified human CCR5 was determined by cryo-EM [83] (

Figure 2B), revealing details of the interactions between gp120 and CCR5, largely consistent with the predictions based on previous mutational data [88][89]. The crown of the V3 loop insets into a deep pocket formed by the 7-TM helices of CCR5. The ECL2 forms a semicircular grip and wraps around the V3 loop, making contact with residues from both the V3 stem and crown. The N terminus of CCR5 and the bridging sheet of gp120 make up the second interface between them, in which the N terminal segment of the coreceptor adopts an extended conformation with several sharp turns and latches onto the surface of the bridging sheet (

3.2. Membrane Fusion

Figure 3.

Figure 2B). The only obvious structural changes were the reconfiguration of the V3 loop and flipping back of the N- and C-termini of gp120 near its interface with gp41. In the prefusion structure of the Env trimer [23][24][25][26][80], gp41 folds into a so-called “4-helix collar” with its four helices [25], wrapping around the N- and C-termini of gp120. If gp120 departures, gp41 would be destabilized and likely enter an irreversible refolding process. Partial or complete gp120 dissociation may, therefore, be the crucial “trigger” that prompts a series of refolding events in gp41 and the membrane fusion process. Indeed, CD4 binding causes a large shift of the C-terminal helix away from the gp120 termini, creating a pocket filled by the fusion peptide [80], which normally packs against the gp120 N-terminus. When the fusion peptide flips away from the pocket because of the intrinsic conformational dynamics, it opens up one side of the gp41 grip on the gp120 termini, and the N-terminal segment of gp120 can then bend back to adopt the conformation seen in the CCR5-bound structure. The replacement of the gp120 termini can prevent the fusion peptide from reoccupying the pocket and effectively weaken the gp120-gp41 association. Spontaneous or CD4-induced gp120 dissociation from the Env trimers has been well documented for many HIV-1 isolates [97][98], indicating that gp120 has the tendency to dissociate from gp41 even without a coreceptor. We note that this model is very similar to that proposed for membrane fusion catalyzed by coronavirus spike proteins, in which dissociation of the receptor-binding subunit initiates the irreversible refolding of the metastable fusion subunit, allowing the fusogenic transition to a stable postfusion structure [99][100].

If CCR5 does not induce further structural rearrangements in gp120 to activate gp41, what is a coreceptor needed for then? First, it would be non-productive if gp120 dissociates prematurely in the absence of a coreceptor, because when a virion attaches to the target cell surfaces with the Env trimer forming a complex only with CD4, the distance between the gp41 fusion peptide and the cell surface is not close enough for it to reach the target membrane. Engaging a coreceptor, which is largely embedded in the membrane, will bring the fusion peptide substantially closer [25]. Second, single-molecule force spectroscopy data using infectious virions and live host cells indicated that the Env-CD4 association is unstable and rapidly reversible unless CCR5 binding immediately follows [101][102]. CCR5 is needed merely to stabilize the CD4-induced conformational changes in Env, which are already sufficient to drive membrane fusion. Third, fusion pore formation probably requires 2–3 Env trimers clustered together [26][90][94], also demonstrated for other viral fusion proteins [103]. A stable Env-receptor complex would help synchronize these trimers to undergo the same conformational changes. Thus, a coreceptor probably functions by stabilizing and anchoring the CD4-induced conformation of the Env trimer near the cell membrane to facilitate productive membrane fusion.