Chronic diarrhoea affects up to 14% of adults, it impacts on quality of life and its cause can be variable. Patients with chronic diarrhoea are presented with a plethora of dietary recommendations, often sought from the internet or provided by those who are untrained or inexperienced. Once a diagnosis is made, or serious diagnoses are excluded, dietitians play a key role in the management of chronic diarrhoea. The dietitian’s role varies depending on the underlying cause of the diarrhoea, with a wide range of dietary therapies available. Dietitians also have an important role in educating patients about the perils and pitfalls of dietary therapy.

- chronic diarrhoea

- diet

- irritable bowel syndrome

- FODMAP

- SIBO

- lactose intolerance

- bile acid diarrhoea

- sucrase-isomaltase deficiency

- dietitian

1. Introduction

Chronic diarrhoea is variably defined but usually includes stools ranging from type 5 to type 7 on the Bristol stool form scale, a duration of more than four weeks, and frequency of stools (usually >25% of the time) [1]. The prevalence of chronic diarrhoea is difficult to determine due to these definition variations [2]. In a population of older adults, 14% were classified as having chronic diarrhoea based on increased stool frequency and the absence of abdominal pain [3]. However, this may include patients with structural or functional causes such as microscopic colitis or chronic diseases such as diabetes. A population-based study from the United States using a validated bowel health questionnaire based on the Bristol stool form scale, reported a prevalence of 6.6% in the adult American population [2].

When dietitians are faced with patients with chronic diarrhoea, it is imperative that a diagnosis is pursued and that sinister diagnoses are excluded. This will involve referral to, and collaboration with, the patient’s General Practitioner or Gastroenterologist. Alarm features that suggest more worrying diagnoses include rectal bleeding, symptoms that wake the patient from sleep, unintentional weight loss, severe unremitting symptoms, a family history of inflammatory bowel disease or colorectal cancer and onset of new symptoms in a patient over the age of 50 years. However, patients without alarm symptoms may also need to undergo appropriate investigations.

Non-invasive investigations could include a full blood count, urea and electrolytes, coeliac serology, iron, vitamin B12 and folate, faecal culture and parasites. A measure of pancreatic exocrine function (e.g., faecal fat concentration or elastase) can be pursued if steatorrhoea is suspected. If indicated, colonoscopy with mucosal biopsy is the gold-standard test to diagnose serious ileocolonic pathology including colorectal cancer, microscopic colitis and inflammatory bowel disease. Other testing can be helpful in specific circumstances including hydrogen and methane breath testing for carbohydrate malabsorption and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth.

Once a diagnosis is made, or serious diagnoses are excluded, dietitians play a key role in the management of chronic diarrhoea. Often the cause may be functional and can lead to a diagnosis of functional diarrhoea (FD) or diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS-D) (Table 1). The dietitian’s role varies depending on the underlying cause of the diarrhoea, with a wide range of dietary therapies available. However, dietitians also have an important role in educating patients about the perils and pitfalls of dietary therapy. Depending upon the cause, if left untreated, chronic diarrhoea may lead to malnutrition and micronutrient deficiencies [4]. Likewise, micronutrient deficiencies may occur when foods or food groups are removed to manage symptoms without considering diet adequacy [5]. Chronic diarrhoea may also impact on quality of life, with increased incidence of depression described in populations of both young [2] and older adults [6].

Table 1. Rome IV criteria for irritable bowel syndrome and functional diarrhoea.

| Rome IV Criteria for Irritable Bowel Syndrome–D, M | Rome IV Criteria for Functional Diarrhoea |

|---|---|

| Abdominal pain on average at least 1 day/week in the last 3 months that is associated with at least 2 of the following | Not usually associated with pain |

|

Loose or watery stools at least 25% of the time |

| Duration of more than three months | Duration of more than three months |

1.1. Diet Seeking Behaviour by Patients with Gastrointestinal Symptoms

Prior to seeing a health professional, patients often identify intolerance to specific foods or food groups, either by trial and error or through doing their own research. The internet has become a platform for seeking such advice [7]. A study comparing the advice provided in blogs by registered dietitians and non-dietitians (non-RD) such as certified holistic nutritionists, nutrition therapists, personal trainers and massage therapists found that non-RD most often provided specific nutrition advice on avoiding foods and promoting supplement use for health conditions including gut disorders [8]. The researchers also found that non-dietitian bloggers used fear-driven strategies and non-evidenced recommendations to support their advice. A survey of 1500 gastroenterologists at the American College of Gastroenterology found that almost 60% of patients seen had made dietary changes prior to their appointment with lactose-reduced and gluten-free diets being the most common [9]. A Swedish study of 197 IBS patients found that 84% reported at least one food as a trigger for their symptoms, with the number of foods identified as problematic increasing linearly in proportion to symptom severity [10]. Dairy and wheat products were commonly avoided [9][10].

This review addresses the diet-responsive causes of chronic diarrhoea, provides an evidence-based overview of diet-based therapies, explores the pearls and pitfalls of each therapy and outlines the role that dietitians have in ensuring the nutritional adequacy and safety of dietary changes.

1.2. Understanding the Role of Diet in the Management of Chronic Diarrhoea

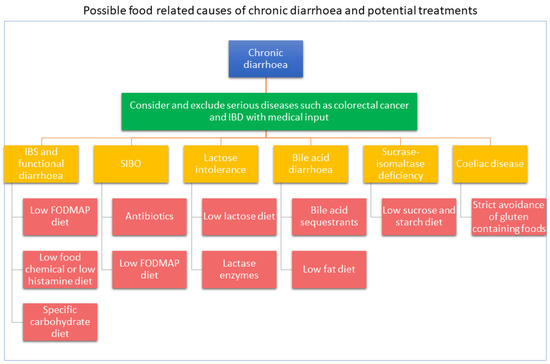

There is a wide range of common causes of diarrhoea that can be classified depending on their responsiveness to dietary therapy (Table 2). The mechanisms for causing diarrhoea are varied and provide the basis for evidence-based dietary interventions. Often dietary therapy is part of a multidisciplinary approach to treat diarrhoea and may include drugs, gut-directed hypnotherapy or stress management. Figure 1 describes evidence-based approaches for the management of chronic diarrhoea.

Figure 1. Evidence-based approaches for the management of chronic diarrhoea.

Table 2. Common causes of chronic diarrhoea—pharmaceutical and dietary responsive.

. Patients may be reacting to other components within food such as fermentable carbohydrates [19][20]. Because this diet therapy is currently unproven it is not included in this review.

Table 3. The pearls and pitfalls of dietary therapies for the management of chronic diarrhoea.

| Disease | Dietary Therapy | Pearls | Pitfalls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) | Low FODMAP diet | The most studied dietary intervention across all age groups. | The long length of time to establish likely trigger foods. | |

| There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books, magazines. | Obsolete and outdated information is likely; resources need regular review by qualified health professionals. | |||

| Comprehensive dietitian training is available. | FODMAP content differs by country. Individual tolerance may differ. | |||

| Commercial product FODMAP testing is available increases consumer choice. | ||||

| Nutritional deficiencies | Phase 1 may restrict prebiotic food intake. | |||

| Review oral intake prior to commencing diet to determine if any already existing nutrient deficiencies | A modified version can be used with those at high risk. | Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | ||

| Small amounts of wheat are allowed so a gluten-free diet is not required. | Phase 1 may reduce abundance of multiple bacterial species. | |||

| High-lactose dairy is avoided. A dairy free diet is not required. | ||||

| Specific-carbohydrate diet | Breaking the Vicious Cycle book provides detailed instruction. | Limited evidence of mechanisms, food composition and efficacy. | ||

| Online support is available. | Long length of time to achieve improvements. | |||

| Discuss suitable food alternatives | ||||

| Consider nutritional supplements for likely nutrient deficits | No evidence of impact on diet adequacy, quality of life and mental health. | |||

| Limited and conflicting guidance on use of the diet and reintroducing foods. | ||||

| Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | ||||

| Likely restricts prebiotic food intake and nutrient intake. | ||||

| Diet restrictiveness | Consider lifestyle and general dietary advice first, e.g., NICE guidelines [17] | |||

| Consider a modified version of the diet [21 | The low-food chemical/low-histamine diet | The Royal Prince Alfred Hospital provides detailed instruction for the low-food chemical diet. | Limited evidence of efficacy. | |

| ][22] | ||||

| Discuss food swaps where examples of food alternatives are given for each suggested eliminated food | There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | |||

| Develop a personalised plan during dietary eliminations [23] | Limited and conflicting food chemical content data. | |||

| Provide shopping lists of suitable alternatives | Relatively short elimination period. | Triggers may be non-diet related. | ||

| Provide recipe ideas and discuss meal planning | ||||

| Reintroduce restricted foods in a timely manner if improvements with symptoms or advise return to usual diet if not improvement was experienced | ||||

| Develop a personalised plan to include previously restricted foods that have been tolerated during the reintroduction phase | ||||

| Encourage frequent reintroduction of identified trigger foods, if appropriate, to test if threshold tolerance has increased | ||||

| Changes in the microbiome | Promote diet diversity to prevent reducing fermentable fibre [24], encourage allowed foods that may not have been eaten before starting the diet | A modified version can be used with those at high risk. | ||

| Encourage vegetables or fruit at all meal times, pectin-containing fruit and vegetables may be better tolerated prebiotics | Likely restricts prebiotic and nutrient intake. | |||

| [24] | May address a wider range of intolerances. | Restrictive diets may contribute to disordered eating patterns. | ||

| Encourage a fibre supplement if fibre intake is likely to be low [25 | Small intestinal bacteria overgrowth (SIBO) | Low FODMAP diet | Excellent support information available. | Online information is prevalence, but given the lack of evidence in this field, it is likely to lack any validity. |

| Dietary changes may not be needed if antibiotics are effective | Reoccurrence of SIBO is common, risking nutritional deficiencies if repeated dietary restriction is conducted. | |||

| Elemental diet | Nutritional complete | Provides no fibre and restricts prebiotics. | ||

| Patients may not require any dietary restrictions. | May not be palatable and therefore poorly tolerated. | |||

| ] | Lactose intolerance | Low-lactose diet | Credible methods for diagnosing are available. | Lactose-free products or lactase enzymes may not be easily available or affordable for all. |

| Suitable alternatives are available providing nutrition in similar amounts. | Risk of low intake of calcium and vitamin D. | |||

| High-lactose dairy is avoided. A dairy free diet is not required. | ||||

| Bile acid diarrhoea | Low-fFat diet | May be better tolerated than bile acid sequestrants. | Risk of inadequate intake of fat-soluble vitamins and reduction in overall energy intake leading to unintended weight loss. | |

| Dietary changes may not be needed if bile acid sequestrants are effective | A variety of low-fat products are readily available at same cost to the full fat varieties. | |||

| Sucrase-isomaltase deficiency (SID) | Low-sucrose/starch diet | There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | Limited research on the long-term management of dietary changes. | |

| Oral enzymes are available to allowing for a broader range of foods to be eaten. | Sucrose enzymes are not available in all countries. | |||

| With good planning the diet can still provide adequate fibre. | May restrict prebiotic food intake. | |||

| Limited research on the long-term management of dietary changes. | ||||

| Coeliac disease | Gluten-free diet | Gold standards for diagnosis. | Lifelong avoidance of all gluten-containing food is required. | |

| Gluten-free food alternatives are readily available. | Cross contamination can occur. | |||

| There are multiple resources; designated websites, apps, recipes, Facebook pages, books. | Gluten-free alternatives can be more expensive, reducing diet compliance for some. |

| Common Causes of Chronic Diarrhoea | Mechanism | Dietary Management |

|---|---|---|

| Predominantly pharmaceutical responsive | ||

| Pancreatic insufficiency | Insufficient secretion of pancreatic digestive enzymes into the small intestine | Teaching patients sources of fat so they are able to titrate digestive enzymes effectively |

| Microscopic colitis | Inflammation occurring at a microscopic level in the lining of the large intestine | N/A |

| Combination of pharmaceutical and dietary responsive | ||

| Short-bowel syndrome | Reduced mucosal surface due to removal or damage of part of the small intestine | Dietary manipulation to enhance absorption such as small frequent meals, higher protein and less refined sugar |

| Inflammatory bowel diseases | Chronic intestinal inflammation occurring throughout the gastrointestinal tract | Dietary and nutrition therapies to manage inflammation and promote maintenance of remission |

| Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth | Overgrowth of colonic bacteria in the small intestine | Restriction of fermentable carbohydrates (the low FODMAP diet) or an elemental diet may reduce overgrowth if antibiotics have not been responsive |

| Bile acid diarrhoea | Excess bile acids entering the large intestine | A low-fat diet may reduce the production of bile acids |

| Predominantly dietary responsive | ||

| Irritable bowel syndrome | Mechanisms are not clearly understood but could be due to increased gut transit, visceral hypersensitivity or altered gut microbiome | Dietary strategies could include: reducing portion sizes, regular eating, reducing fermentable carbohydrates or reducing natural food chemicals |

| Lactose intolerance | Reduced lactase enzyme activity in the small intestine | Limiting lactose-containing milk and milk products |

| Sucrase-isomaltase intolerance | Reduced enzyme activity of sucrase and or isomaltase in the small intestine | Reducing dietary intake of foods containing sucrose, isomaltose and maltose |

| Coeliac disease | Genetic condition resulting in damage to the lining of the small intestine when gluten is consumed | A strict lifelong gluten-free diet resolves symptoms and results in healing the lining of the small intestine |

2. Dietary Management of Chronic Diarrhoea

2.1. Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and Functional Diarrhoea

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 4–20% of the population [11]. Women are more likely than men to be diagnosed with IBS, and its prevalence, based on the Rome IV criteria (Table 1), is greater in the 30–45 year age group and for those living in Western countries [11]. IBS results in changes in bowel habits, bloating, pain and nausea. It also impacts energy levels [10] and quality of life [10][12] and is a common reason for visits to general practice [13], yet its aetiology remains unclear. IBS can persist for many years and develop at any age. A ten year follow-up study of over 8000 patients enrolled in a screening programme found that almost two-thirds of patients with IBS continued to have symptoms at follow up, while 28% of patients without symptoms at baseline subsequently developed IBS [14].

To diagnose IBS, abdominal pain must be present, and other gut-related causes eliminated such as coeliac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer or diverticulitis. The Rome criteria classifies IBS as diarrhoea predominant (IBS–D), constipation predominant (IBS–C), mixed bowel habits (IBS-M) or unclassified (IBS-U) [15]. FD is diagnosed in those with diarrhoea but not abdominal pain.

2.1.1. Dietary Therapies for IBS

First-line dietary advice such as eating regularly, limiting intake of high-fibre food, reducing the intake of alcohol, caffeine, fizzy drinks and managing stress is sufficient to resolve IBS symptoms for up to 50% of patients [16][17]. If symptoms persist, a trial of an elimination diet to identify specific foods that trigger IBS symptoms may be warranted. There are a number of elimination diets described in the literature. The following sections outline three elimination diets, the evidence to support their use and the pearls and pitfalls of each dietary treatment (Table 3). Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity, which is often reported by patients, remains difficult to diagnose and define [18]

Table 4. Pitfalls of the dietary management of chronic diarrhoea and management strategies.

| Potential Pitfall | Management Strategy |

|---|---|

| Unnecessary use of restrictive diet | Rule out other potential causes such as IBD, coeliac disease, diverticular disease, colorectal cancer [17] |

| Consider general lifestyle and dietary advice first such as the NICE guidelines [17] | |

| Diagnostic testing to rule out SIBO and lactose malabsorption if available |

References

- Arasaradnam, R.P.; Brown, S.; Forbes, A.; Fox, M.R.; Hungin, P.; Kelman, L.; Major, G.; O’Connor, M.; Sanders, D.S.; Sinha, R.; et al. Guidelines for the investigation of chronic diarrhoea in adults: British Society of Gastroenterology. Gut 2018, 67, 1380–1399.

- Singh, P.; Mitsuhashi, S.; Ballou, S.; Rangan, V.; Sommers, T.; Cheng, V.; Iturrino-Moreda, J.; Friedlander, D.; Nee, J.; Lembo, A. Demographic and Dietary Associations of Chronic Diarrhea in a Representative Sample of Adults in the United States. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2018, 113, 593–600.

- Talley, N.J.; O’Keefe, E.A.; Zinsmeister, A.R.; Melton III, L.J. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: A population-based study. Gastroenterology 1992, 102, 895–901.

- Gorospe, E.C.; Oxentenko, A.S. Nutritional consequences of chronic diarrhoea. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2012, 26, 663–675.

- McCoubrey, H.; Parkes, G.; Sanderson, J.; Lomer, M. Nutritional intakes in irritable bowel syndrome. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2008, 21, 396–397.

- Ganda Mall, J.-P.; Östlund-Lagerström, L.; Lindqvist, C.M.; Algilani, S.; Rasoal, D.; Repsilber, D.; Brummer, R.J.; Keita, A.V.; Schoultz, I. Are self-reported gastrointestinal symptoms among older adults associated with increased intestinal permeability and psychological distress? BMC Geriatr. 2018, 18, 75.

- Bianco, A.; Zucco, R.; Nobile, C.G.A.; Pileggi, C.; Pavia, M. Parents Seeking Health-Related Information on the Internet: Cross-Sectional Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013, 15, e204.

- Chan, T.; Drake, T.; Vollmer, R.L. A qualitative research study comparing nutrition advice communicated by registered Dietitian and non-Registered Dietitian bloggers. J. Commun. Health 2020, 13, 55–63.

- Lenhart, A.; Ferch, C.; Shaw, M.; Chey, W.D. Use of Dietary Management in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: Results of a Survey of Over 1500 United States Gastroenterologists. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2018, 24, 437–451.

- Böhn, L.; Störsrud, S.; Törnblom, H.; Bengtsson, U.; Simrén, M. Self-Reported Food-Related Gastrointestinal Symptoms in IBS Are Common and Associated With More Severe Symptoms and Reduced Quality of Life. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 108, 634–641.

- Sperber, A.D.; Bangdiwala, S.I.; Drossman, D.A.; Ghoshal, U.C.; Simren, M.; Tack, J.; Whitehead, W.E.; Dumitrascu, D.L.; Fang, X.; Fukudo, S.; et al. Worldwide Prevalence and Burden of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders, Results of Rome Foundation Global Study. Gastroenterology 2021, 160, 99–114.

- El-Salhy, M.; Østgaard, H.; Hausken, T.; Gundersen, D. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol. Med. Rep. 2012, 5, 1382–1390.

- Card, T.R.; Canavan, C.; West, J. The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clin. Epidemiol. 2014, 6, 71–80.

- Ford, A.C.; Forman, D.; Bailey, A.G.; Axon, A.T.R.; Moayyedi, P. Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A 10-Yr Natural History of Symptoms and Factors That Influence Consultation Behavior. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008, 103, 1229–1239.

- Schmulson, M.J.; Drossman, D.A. What Is New in Rome IV. J. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 23, 151–163.

- McKenzie, Y.A.; Bowyer, R.K.; Leach, H.; Gulia, P.; Horobin, J.; O’Sullivan, N.A.; Pettitt, C.; Reeves, L.B.; Seamark, L.; Williams, M.; et al. British Dietetic Association systematic review and evidence-based practice guidelines for the dietary management of irritable bowel syndrome in adults (2016 update). J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 29, 549–575.

- National Institute for Health Clinical Excellence. Irritable Bowel Syndrome in Adults: Diagnosis and Management of IBS in Primary Care. NICE. Available online: (accessed on 8 May 2018).

- Gibson, P.R.; Skodje, G.I.; Lundin, K.E.A. Non-coeliac gluten sensitivity. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 32, 86–89.

- Ajamian, M.; Rosella, G.; Newnham, E.D.; Biesiekierski, J.R.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. Effect of Gluten Ingestion and FODMAP Restriction on Intestinal Epithelial Integrity in Patients with Irritable Bowel Syndrome and Self-Reported Non-Coeliac Gluten Sensitivity. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2021, 65, 1901269.

- Biesiekierski, J.R.; Peters, S.L.; Newnham, E.D.; Rosella, O.; Muir, J.G.; Gibson, P.R. No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013, 145, 320–328.

- Halmos, E.P.; Gibson, P.R. Controversies and reality of the FODMAP diet for patients with irritable bowel syndrome. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2019, 34, 1134–1142.

- Scarlata, K.; Catsos, P.; Smith, J. From a Dietitian’s Perspective, Diets for Irritable Bowel Syndrome Are Not One Size Fits All. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 543–545.

- De Roest, R.H.; Dobbs, B.R.; Chapman, B.A.; O'Brien, L.A.; Leeper, J.A.; Hebblethwaite, C.R.; Gearry, R.B. The low FODMAP diet improves gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: A prospective study. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2013, 67, 895–903.

- Gill, S.K.; Rossi, M.; Bajka, B.; Whelan, K. Dietary fibre in gastrointestinal health and disease. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 101–116.

- Moayyedi, P.; Andrews, C.N.; MacQueen, G.; Korownyk, C.; Marsiglio, M.; Graff, L.; Kvern, B.; Lazarescu, A.; Liu, L.; Paterson, W.G.; et al. Canadian Association of Gastroenterology Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS). J. Can. Assoc. Gastroenterol. 2019, 2, 6–29.