Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common birth defect among newborns worldwide and contributes to significant infant morbidity and mortality. Owing to major advances in medical and surgical management, as well as improved prenatal diagnosis, the outcomes for these children with CHD have improved tremendously so much so that there are now more adults living with CHD than children. Advances in genomic technologies have discovered the genetic causes of a significant fraction of CHD, while at the same time pointing to remarkable complexity in CHD genetics.

- cardiogenesis

- cardiac development

- epigenetics

- transcriptional regulation

- congenital heart disease

1. Introduction

Congenital heart disease (CHD) refers to a heterogeneous collection of structural abnormalities of the heart or the great vessels present at birth. It is the most common birth defect in newborns, affecting >1 million live births per annum globally and causing 10% of stillbirths. The moderate and severe forms of CHD affect approximately 6–20 per thousand live-births [1], and is a major cause of infant mortality and morbidity in the developed world [2], accounting for ~40% of infant deaths in North America [3]. In the most recent era, the survival and outcome of CHD patients, including children with complex cardiac defects, have improved significantly such that more than 75% of CHD children who survive the first year may be expected to reach adulthood in developed countries [4]. This increased survival is due to advances in prenatal and postnatal diagnosis, innovation in surgical techniques, as well as improved clinical surveillance and translational research, which have dramatically improved the clinical management of CHD. As a result, there are more adults living with CHD than there are children with CHD [5], Nevertheless, the clinical course of children with complex CHD may be associated with many late sequelae, and affected children sometimes require subsequent invasive procedures and eventual heart transplantation due to heart failure caused by progressive ventricular dysfunction [6].

Thus, a greater understanding of the etiology of CHD is fundamental, in our effort to improve diagnosis, clinical management and counselling on risk of recurrence during subsequent pregnancies. With only 20–30% of cases traced to a known cause [7], the etiologies of CHD may be divided into genetic and non-genetic categories. While non-genetic etiologies of CHD such as environmental teratogens and infectious agents are widely studied [2], there is still a lot yet to be uncovered for the genetics and epigenetics of CHD [2]. With advancement of sequencing techniques, there has been greater appreciation of the significant genetic contribution to CHD in the recent 10–15 years, although its genetic basis was first recognized more than 3 decades earlier [8]. Epidemiology points to a strong genetic contribution in a proportion of CHD [9]. A greater concordance of CHD exists for monozygotic than dizygotic twins, and there is increased risk of recurrence among siblings or subsequent pregnancies [9]. Conversely, it is also notable that for a large proportion of CHD, particularly the severe forms, there is no other family history of CHD. This underlies a significant contribution from de novo genetic events [9]. Despite this, a specific causal genetic mutation is still only recognized in a minority of cases of sporadic CHD [10]. Currently, approximately 35% of CHD cases, with or without extracardiac malformations, can be attributed to genetic factors (Table 1) including monogenic (3–5%) or chromosomal (8–10%) anomalies, and copy number variants (3–25%). Environmental causes (2%) such as maternal diabetes, smoking or alcohol use, are recognized in ~20–30% of patients [1,11,12,13,14][1][11][12][13][14]. The genetics of CHD is also complex; a single candidate gene or genetic variant can produce a spectrum of heart malformations and may even occur in phenotypically-normal humans. Variation in genetic penetrance also occurs in affected families, resulting in a range of CHD phenotypes in the same pedigree [15,16][15][16].

Table 1. Genes and loci commonly associated with syndromic congenital heart disease.

Syndrome | Genes | Loci | Cardiac Disease | % CHD | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Alagille | JAG 1 | NOTCH2 | 20p12.2 | 1p12-p11 | PPS, TOF, PA | >90 |

.

There remains much to be learned about the genetic and epigenetic bases of CHD, which we are only now beginning to understand through tissue, animal and computational modelling. Multiple experimental animal models have provided invaluable understanding into the molecular mechanisms of CHD. In humans, the basis of these molecular mechanisms remains poorly understood owing to its complexity. Moreover, most CHDs are not part of any genetic syndrome i.e., sporadic malformations, with neither a family history nor a clear Mendelian inheritance of the disease [8]. Whole exome and genome sequencing efforts reveal mutations in genes that contribute to CHD [17], but mutations in protein coding genes only account for 35% of CHD [9]. Importantly, many of these protein coding genes are now recognized as those encoding components of the epigenetic molecular pathways (e.g., histone modifying enzymes), underpinning a causality hypothesis for “molecular epigenetics”, or pathways that regulate networks of gene expression [9].

2. Overview of Congenital Heart Disease

As CHD comprises a heterogeneous group of cardiac malformations, the key clinical manifestation is dependent on the type of CHD. Since Maude Abbott developed The Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease more than a century ago, the classification of CHD has evolved substantially [18]. Broadly speaking, CHD can be classified, based on morphology and hemodynamics, into cyanotic and acyanotic CHD. Cyanosis is a bluish discoloration of the skin and mucous membrane resulting from reduced oxygen saturation in the circulating blood. Patients with cyanotic CHD have mixing of deoxygenated with oxygenated blood, with overall reduction of circulating oxyhemoglobin.

Common examples of acyanotic CHD include atrial septal defect (ASD) and ventricular septal defect (VSD). In ASD, there is a defect/hole in the septum/wall that divides the left and right atria; in VSD, the defect is in the septum between the left and right ventricles. Notably, VSD is one of the commonest congenital malformation of the heart. Atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), also known as endocardial cushion or atrioventricular canal defect, comprises of a defect in atrioventricular septum, and malformed atrioventricular valves. In these defects, oxygenated blood shunts from the oxygen-rich (left) chambers to the oxygen-poor (right) chambers; therefore, these lesions are also termed left-to-right shunts. As the mixing is from the oxygenated to the deoxygenated chambers, there is no reduction in the oxygen saturation in the systemic circulation. However, this may result in increased pulmonary blood flow with consequent lung congestion.

Cyanotic CHD encompass defects such as tetralogy of Fallot, pulmonary atresia, transposition of the great arteries, double outlet right ventricle, persistent truncus arteriosus, tricuspid atresia, and total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage, to name a few. Table 2 summarizes the common types of cyanotic CHD.

Table 2. Cyanotic congenital heart diseases.

Cyanotic CHD | Brief Description |

|---|

21]. Overall, epigenetics are heritable, and mutations in single gene responsible for these mechanisms can lead to dysregulation on an array of genes leading to polygenic diseases including CHD. Here, we describe the list of genes implicated in CHD across the different mechanisms. Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 summarize the current available literature of human studies.

Table 3. DNA methylation in CHDs.

DNA Methylation | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Allele | Clinical Sample Size | Modification | Tissue Type | Cardiac Disease Phenotype | |||||||||||||

* Repetitive Long Interspersed Nucleotide Element-1. Cardiac disease abbreviations: ADA (Absent Ductus Arteriosus), ASD (Atrial Septal Defects), AVA (Aortic Valve Atresia), AVSD (Atrioventricular Septal Defect), CoA (Coarctation of the pre-ductal Aorta), DCRV (Double-Chambered Right Ventricle), DORV (Double Outlet Right Ventricle), HAA (Hypoplasia of the Ascending Aorta), HLHS (Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome), LHH (Left Heart Hypoplasia), MVA (Mitral Valve Atresia), PFO (Patent Foramen Ovale), RHH (Right Heart Hypoplasia), TA (Truncus Arteriosus), (Tetralogy of Fallot), TVS (Tricuspid Valve Stenosis), VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect).

Table 4. Histone modifications in CHDs.

Histone Modification | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Allele | Clinical Sample Size | Modification | Source Type | Reference | ||||||||||||||||||||

Cardiac Disease Phenotype | Reference | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) | A common cyanotic CHD; characterized by pulmonary stenosis/right ventricular outflow tract obstruction, VSD, over-riding aorta and hypertrophy of the right ventricle | CFC | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Transposition of the great arteries (TGA) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

NOX5 | 21 VSD and 15 controls | Hypermethylation | Fetal myocardial tissue | VSD | ||||||||||||||||||||

WHSC1 | Case study | H3K36me3 | In vivo mouse models [94] | [38] |

[78] |

[22] |

||||||||||||||||||

BRAF | KRAS | Discordant ventriculoarterial connection—the right ventricle is connected to the aorta (instead of pulmonary artery), and left ventricle to pulmonary artery (instead of aorta) MAP2K1 | MAP2K2 | 7q34 | 12p12.1 | 15q22.31 | 19p13.3 | PVS, ASD, HCM | 75 | |||||||||||||||

Cantu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Double outlet right ventricle (DORV) | ABCC9 |

Both the aorta and pulmonary artery arise predominantly or completely, from the right ventricle | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Persistent truncus arteriosus | Failure of septation of the primitive truncus into the aorta and pulmonary artery, resulting in a single, common arterial trunk that overlies a large VSD | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | Underdevelopment of the left-sided structures of the heart, including the ascending aorta, left ventricle and aortic and mitral valves | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Note: TOF, TGA, DORV, and persistent truncus arteriosus are collectively known as conotruncal defects, as these lesions involve the conus and truncus arteriosus of the embryonic heart.

TOF, TGA, DORV, and persistent truncus arteriosus are collectively known as conotruncal defects, as these lesions involve the conus and truncus arteriosus of the embryonic heart.

3. Overview of Cardiogenesis and Transcriptional Events during Cardiac Development

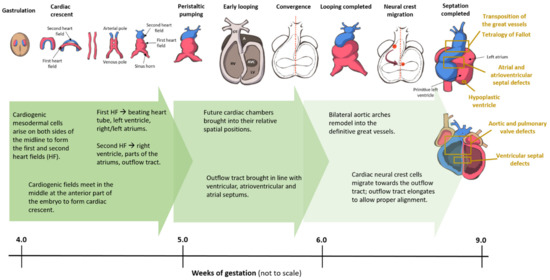

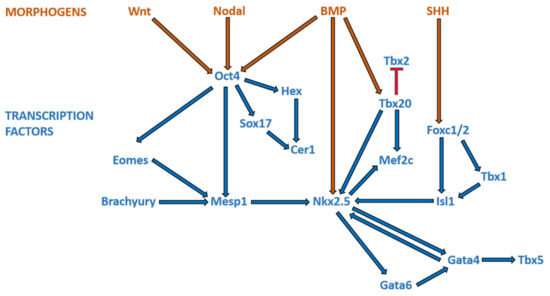

Broadly speaking, CHD can be considered as the consequence of normal cardiac development gone awry. Heart development or cardiogenesis, is a complex developmental process (Figure 1) governed by multiple interlinked and dose-dependent pathways [19]. Owing to the complexity of the developmental processes governing morphogenesis of the heart, impairment in any of these steps understandably leads to CHD. These events increase the difficulty of identifying and characterizing the genetic risk factors for CHD, and emphasizes the importance of understanding cardiogenesis at the molecular level. Therefore, an overview of the cardiac developmental events and their transcriptional regulation (Figure 2) would be pertinent to provide context to understanding the developmental defects causing CHD.

Figure 1. Cardiac development in the human embryo. This schematic shows the embryonic development of the human heart through first and second heart field formation, heart tube formation and pumping, looping, neural crest migration and septation, resulting in a fully developed heart at the end of gestation. HF: heart field.

Figure 2. Morphogens and transcriptional factors regulating cardiac cell lineage and differentiation. Note: Blue arrows indicate activation; red arrows indicate inhibition.

4. Epigenetics and Congenital Heart Disease

The expression of thousands of genes in millions of cells in a single organism must be tightly regulated, during development and throughout its life. Although the genotype of most cells of a given organism is the same (except the gametes and the cells of the immune system), multiple cell types and functions emerge owing to highly regulated gene activity. Gene activity is largely mediated by transcriptional regulation, which is in turn orchestrated by epigenetic mechanisms. Although the definition of epigenetics may have evolved over time, Conrad Waddington in the 1950s proposed that, “An epigenetic trait is a stably heritable phenotype resulting from changes in a chromosome without alterations in the DNA sequence” [76][20]; and this can involve the heritability of a phenotype, passed on through either mitosis or meiosis. The mechanisms that govern epigenetics comprise of DNA methylation, histone modifications, higher-order chromatin structure, and the activity of certain non-coding RNA species [77][

HLH; WHS | [ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

KIAA0310; RAB43; NDRG2 | 21 VSD and 15 controls | Hypermethylation | Fetal myocardial tissue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

MLL2; CHD7; WDR5; KDM5A; KDM5B | VSD |

[79] |

[23] |

362 severe CHD cases and 264 controls | H3K4me | Whole blood | LVO; CTD |

[97] |

[41] |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

UBE2B; RNF20; USP44 | 12p12.1 | PDA, BAV, HCM, CoA, PE, AS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SIVA1 | Hypomethylation | H2BK120 | 75 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CTD; HTX; LVO | Char | TFAP2B | 6p12.3 | PDA, VSD | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

LINE-1* | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SMAD2 | 48 TOF patients and 16 controls [81] | [ |

H3K27 | 58 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

] | Hypomethylation | HTX | Right ventricular tissue samples [80][24]; Right ventricular outflow tracts [81] | [25] |

TOF |

[80] |

[24] |

CHARGE | CHD7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NKX2.5; HAND1; EGFR; EVC2; TBX5; CFC1B | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

EBAF | 30 TOF and 6 controls [82][26]; 41 TOF and 6 control [838q12 | ] | [27] |

16 VSD and 16 normal fetuses at 22–28 weeks of gestation. | TOF, PDA, DORV, AVSD, VSD | Hypermethylation | H4ac | Right ventricular myocardium tissues | 75–85 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TOF, HLHS | Myocardial tissue | VSD |

[98] |

[42] |

Costello | HRAS | 11p15.5 | PVS, ASD, VSD, HCM, arrhythmias | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

GATA4; MSX1 | 6 Down syndrome with CHD, 6 Down syndrome without CHD, 6 isolated heart malformations, and 4 control | Hypermethylation | Whole heart tissue | 44–52 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AVSD, VSD, CoA, TOF, LHH, HAA, DORV, VSD, TOF, MVA, AVA, PFO, TVS; RHH, TA; ADA; TAV | [ | 84] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

RNF20; RNF40; UBE2B | 2645 case trios and 1789 control trios. | H2Bub1 | Whole blood or sputum |

[28] |

Dextrocardia; RAI; TAPVR; CAVC; PA; L-TGA; HLHS; TOF, RAA |

DiGeorge | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[ | ] |

[43] |

SCO2 | TBX1 | 8 TOF, 8 ventricular septal defect, and 4 control | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

JMJD1C; RREB1; MINA; KDM7A | 89 severe CHD cases and 95 controls | 22q11.2 | deletion | Hypermethylation | Conotruncal defects, VSD, IAA, | ASD, VR | 74–85 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Myocardial biopsies | TOF, VSD | H3K27/H3K9 | Whole blood | CTD | [85] |

[29] |

[100] |

[44] |

Ellis-van Creveld | EVC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ZFPM2 | EVC2 | 43 TOF and 6 controls | 4p16.2 | 4p16.2 | Hypermethylation | Common atrium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

KAT2B | Right ventricular outflow tract | 60 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TOF | 400 Chinese Han |

[86] | HAT | Whole blood | TOF, TA and TGA, VSD, AVSD and PDA[30] |

[101] |

[45] |

Holt-Oram | TBX5 | 12q24.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

p16INK4a | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PRDM6 | 63 TOF and 75 controls | 35 individuals and their extended kindreds | Hypermethylation | VSD, ASD, AVSD, conduction defects | H3K9me2/H4K20me2 | 50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whole blood | Whole blood | TOF | N-PDA | [87] |

[31] |

[102] |

[46] |

Kabuki | KMT2D | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

BRG1 | KDM6A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

KANSL1 | 24 CHD and 11 controls | 12q13 | Xp11.3 | Hypomethylation | CoA, BAV, VSD, TOF, TGA, HLHS | Various cardiac tissues. | 50 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TOF, VSD, DCRV | 253 diseased patients | H4K16ac | Whole blood[88] |

[32] |

TOF |

[103] |

[47] |

Noonan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

PTPN11 | SOS1 | RAF1 | KRAS | NRAS | RIT1 | SHOC2 | SOS2 | BRAF | 12q24.13 | 2p22.1 | 3p25.2 | 12p12.1 | 1p13.2 | 1q22 | 10q25.2 | 14q21.3 | 7q34 | MTHFR | Dysplastic PVS, ASD, TOF, AVSD, | HCM, VSD, PDA | 40 Down syndrome without CHD; 40 mothers of Down syndrome with CHD, and 40 age matched control mothers | Hypermethylation | Whole blood | 75 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AVSD; VSD, ASD; TOF | [ | 89] |

[33] |

Williams-Beuren | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

TBX20 | 7q11.23 | 23 TOF and 5 controls [90] deletion (ELN) | [34 | 7q11.23 | ] | SVAS, PAS, VSD, ASD | 80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

; 42 TOF and 6 controls | [91] | [35] |

Hypomethylation | Right ventricular myocardial tissues | TOF |

[90] |

[34] |

Carpenter | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

ZIC3; RAB23 | 6p11.2 | NR2F2 | VSD, ASD, PDA, PS, TOF, TGA |

Monozygotic twin pair discordant for DORV | Hypermethylation | 50 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Whole blood | DORV |

[92] |

[36] |

Coffin-Siris | ARID1B | SMARCB1 | ARID1A | SMARCB1 | SMARCA4 | SMARCE1 | 6q25 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

NRG1 | 7 Down syndrome patients with CHD and 9 Down syndrome without CHD | 22q11 | 1p36.1 | 22q11.23 | 19p13.2 | 17q21.2 | Hypermethylation | ASD, AVSD, VSD, MR, PDA, PS, DEX, AS | Whole blood | 20–44 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Endocardial cushion-type | [ | 93] |

[37] |

Cornelia de Lange | NIPBL | SMC1L1 | SMC3 | 5p13 | Xp11.22 | 10q25 | PVS, VSD, ASD, PDA | 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mowat-Wilson | ZEB2 | 2q22.3 | VSD, CoA, ASD, PDA, PAS | 54 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rubinstein-Taybi | CBP | EP300 | 16p13.3 | 22q13.2 | PDA, VSD, ASD, HLHS, BAV | 33 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Smith-Lemli-Opitz | DHCR7 | 11q12-13 | AVSD, HLHS, ASD, PDA, VSD | 50 |

Abbreviations: AS, aortic stenosis; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; BAV, bicuspid aortic valve; CFC, cardiofaciocutaneous; CHARGE, coloboma, heart defects, choanal atresia, retarded growth and development, genital anomalies, and ear anomalies; CoA, coarctation of the aorta; DEX, dextrocardia; DORV, double-outlet right ventricle; HCM, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; CHD, congenital heart disease; HLHS, hypoplastic left heart syndrome; IAA, interruption of aortic arch; MR, mitral regurgitation; PA, pulmonary atresia; PAS, pulmonary artery stenosis; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PE, pericardial effusion; PPS, peripheral pulmonary stenosis; PS, pulmonary stenosis; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; SVAS, supravalvular aortic stenosis; TGA, transposition of great arteries; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VR, vascular ring; and VSD, ventricular septal defect. Note: % CHD denotes the proportion of patients with the particular genetic syndrome affected by CHD. Adapted from [7]

Cardiac disease abbreviations: AVSD (Atrioventricular Septal Defect), CAVC (Complete Atrioventricular Canal), CTD (Conotruncal Defects), HLH (Hypoplastic left heart), HLHS (Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome), HTX (Heterotaxy), L-TGA (Levo-Transposition of The Great Arteries), LVO (Left Ventricular Obstruction), N-PDA (Nonsyndromic Patent Ductus Arteriosus), PA (Pulmonary Atresia), PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus), RAA (Right Aortic Arch), RAI (Right Atrial Isomerism), TA (Truncus Arteriosus), TAPVR (Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Return), TGA (Transposition of the Great Arteries), TOF (Tetralogy of Fallot), VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect), WHS (Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome).

Table 5. Non-coding RNA in CHDs.

Non-Coding RNA | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Allele | Clinical Sample Size | Modification | Tissue Type | Cardiac Disease Phenotype | Reference | ||||||||||||

miR-196a (rs11614913 CC) | 1324 CHD and 1783 controls | Increased mature miR-196a expression | Whole blood | TOF, VSD; ASD |

[104] |

[48] |

|||||||||||

miR-1-1 | 28 VSD and 9 controls | Upregulates GJA1 and SOX9 | Heart tissue | VSD |

[105] |

[49] |

|||||||||||

miR-181c | Downregulates BMPR2 | VSD | |||||||||||||||

miR-1, miR-206 | 30 TOF and 10 controls | Upregulates Cx43 | Myocardium tissue | TOF |

[106] |

[50] |

|||||||||||

let-7e-5p; miR-222-3p; miR-433 | 3 VSD and 3 controls | Downregulated | Blood plasma | VSD |

[107] |

[51] |

|||||||||||

miR-184 | 10 CHD and 10 controls | Downregulated | Right ventricular outflow tract | Cyanotic cardiac defects |

[108] |

[52] |

|||||||||||

miRNA-139-5p | 5 family individuals | (c.1784T > C) gain-of-function | Whole blood | ASDII |

[109] |

[53] |

|||||||||||

miR-518e, miR-518f, and miR-528a | 7 Down syndrome patients with AVSD and 22 Down syndrome patients without CHD | Downregulates AUTS2 | Down syndrome lymphoblastoid cell lines (GSE34457) | AVSD |

[110] |

[54] |

|||||||||||

miR-518a, miR-518e, miR-518f, and miR-96 | Downregulates KIAA2022 | ||||||||||||||||

miR-138 (rs139365823) | 857 CHD and 938 controls | Upregulates miR-138 | Whole blood | VSD; ASD; TOF; PDA |

[111] |

[55] |

|||||||||||

Cardiac disease abbreviations: ASD (Atrial Septal Defects), ASDII (Isolated ostium secundum atrial septal defect), AVSD (Atrioventricular Septal Defect), PDA (Patent Ductus Arteriosus), TOF (Tetralogy of Fallot), VSD (Ventricular Septal Defect).

References

- Hoffman, J.I.; Kaplan, S. The incidence of congenital heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2002, 39, 1890–1900.

- Fahed, A.C.; Gelb, B.D.; Seidman, J.G.; Seidman, C.E. Genetics of congenital heart disease: The glass half empty. Circ. Res. 2013, 112, 707–720.

- Agopian, A.J.; Goldmuntz, E.; Hakonarson, H.; Sewda, A.; Taylor, D.; Mitchell, L.E. Pediatric Cardiac Genomics Consortium* Genome-Wide Association Studies and Meta-Analyses for Congenital Heart Defects. Circ. Cardiovasc. Genet. 2017, 10, e001449.

- Zimmerman, M.S.; Smith, A.G.C.; Sable, C.A.; Echko, M.M.; Wilner, L.B.; Olsen, H.E.; Atalay, H.T.; Awasthi, A.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Boucher, J.L.; et al. Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4, 185–200.

- Marelli, A.J.; Ionescu-Ittu, R.; Mackie, A.S.; Guo, L.; Dendukuri, N.; Kaouache, M. Lifetime Prevalence of Congenital Heart Disease in the General Population From 2000 to 2010. Circulation 2014, 130, 749–756.

- Bacha, E.A.; Cooper, D.; Thiagarajan, R.; Franklin, R.C.; Krogmann, O.; Deal, B.; Mavroudis, C.; Shukla, A.; Yeh, T.; Ba-rach, P.; et al. Cardiac complications associated with the treatment of patients with congenital cardiac disease: Consensus definitions from the Multi-Societal Database Committee for Pediatric and Congenital Heart Disease. Cardiol. Young 2008, 18 (Suppl. 2), 196–201.

- Pierpont, M.E.; Brueckner, M.; Chung, W.K.; Garg, V.; Lacro, R.V.; McGuire, A.L.; Mital, S.; Priest, J.R.; Pu, W.T.; Roberts, A.; et al. Genetic Basis for Congenital Heart Disease: Revisited: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2018, 138, e653–e711.

- Pierpont, M.E.; Basson, C.T.; Benson, D.W.; Gelb, B.D.; Giglia, T.M.; Goldmuntz, E.; McGee, G.; Sable, C.A.; Srivastava, D.; Webb, C.L. Genetic Basis for Congenital Heart Defects: Current Knowledge—A scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Circulation 2007, 115, 3015–3038.

- Zaidi, S.; Brueckner, M. Genetics and Genomics of Congenital Heart Disease. Circ. Res. 2017, 120, 923–940.

- Mitchell, M.E.; Sander, T.L.; Klinkner, D.B.; Tomita-Mitchell, A. The Molecular Basis of Congenital Heart Disease. Semin. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007, 19, 228–237.

- Cowan, J.R.; Ware, S.M. Genetics and Genetic Testing in Congenital Heart Disease. Clin. Perinatol. 2015, 42, 373–393.

- Kuciene, R.; Dulskiene, V. Selected environmental risk factors and congenital heart defects. Medicina 2008, 44, 827.

- Meberg, A.; Hals, J.; Thaulow, E. Congenital heart defects—Chromosomal anomalies, syndromes and extracardiac malformations. Acta Paediatr. 2007, 96, 1142–1145.

- Van Der Bom, T.; Zomer, A.C.; Zwinderman, A.H.; Meijboom, F.J.; Bouma, B.J.; Mulder, B.J.M. The changing epidemiology of congenital heart disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2010, 8, 50–60.

- Brown, C.B.; Wenning, J.M.; Lu, M.M.; Epstein, D.J.; Meyers, E.N.; Epstein, J.A. Cremediated excision of Fgf8 in the Tbx1 expression domain reveals a critical role for Fgf8 in cardiovascular development in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2004, 267, 190–202.

- Farr, G.H.; Imani, K.; Pouv, D.; Maves, L. Functional testing of a human PBX3 variant in zebrafish reveals a potential modifier role in congenital heart defects. Dis. Model. Mech. 2018, 11, dmm035972.

- Jin, S.C.; Homsy, J.; Zaidi, S.; Lu, Q.; Morton, S.; DePalma, S.R.; Zeng, X.; Qi, H.; Chang, W.; Sierant, M.C.; et al. Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nat. Genet. 2017, 49, 1593–1601.

- Millar, R.; Barnhart, W.S. Dr. Maude Abbott’s Atlas of Congenital Cardiac Disease. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 1936, 34, 194–195.

- Witman, N.; Zhou, C.; Beverborg, N.G.; Sahara, M.; Chien, K.R. Cardiac progenitors and paracrine mediators in cardiogenesis and heart regeneration. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 100, 29–51.

- Waddington, C.H. Genetic Assimilation of the Bithorax Phenotype. Evolution 1956, 10.

- Feinberg, A.P. The Key Role of Epigenetics in Human Disease Prevention and Mitigation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 1323–1334.

- Zhu, C.; Yu, Z.-B.; Chen, X.-H.; Ji, C.-B.; Qian, L.-M.; Han, S.-P. DNA hypermethylation of the NOX5 gene in fetal ventricular septal defect. Exp. Ther. Med. 2011, 2, 1011–1015.

- Zhu, C.; Yu, Z.B.; Chen, X.H.; Pan, Y.; Dong, X.Y.; Qian, L.M.; Han, S.-P. Screening for differential methylation status in fetal myocardial tissue samples with ventricular septal defects by promoter methylation microarrays. Mol. Med. Rep. 2010, 4, 137–143.

- Sheng, W.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Zheng, F.; Chen, L.; Huang, G.; Ma, D. LINE-1 methylation status and its association with tetralogy of fallot in infants. BMC Med. Genomics 2012, 5, 20.

- Sheng, W.; Qian, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, P.; Chen, L.; Ma, D.; Huang, G. Association between mRNA levels of DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, MBD2 and LINE-1 methylation status in infants with tetralogy of Fallot. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2013, 32, 694–702.

- Sheng, W.; Qian, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Zhang, P.; Diao, L.; An, Q.; Chen, L.; Ma, D.; Huang, G. DNA methylation status of NKX2-5, GATA4 and HAND1in patients with tetralogy of fallot. BMC Med. Genomics 2013, 6, 46.

- Sheng, W.; Qian, Y.; Zhang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Chen, L.; Ma, D.; Huang, G. Association of promoter methylation statuses of congenital heart defect candidate genes with Tetralogy of Fallot. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 31.

- Serra-Juhé, C.; Cuscó, I.; Homs, A.; Flores, R.; Torán, N.; Pérez-Jurado, L.A. DNA methylation abnormalities in congenital heart disease. Epigenetics 2015, 10, 167–177.

- Grunert, M.; Dorn, C.; Cui, H.; Dunkel, I.; Schulz, K.; Schoenhals, S.; Sun, W.; Berger, F.; Chen, W.; Sperling, S.R. Comparative DNA methylation and gene expression analysis identifies novel genes for structural congenital heart diseases. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 112, 464–477.

- Sheng, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Ma, D.; Huang, G. CpG island shore methylation of ZFPM2 is identified in tetralogy of fallot samples. Pediatr. Res. 2016, 80, 151–158.

- Gao, S.-J.; Zhang, G.-F.; Zhang, R.-P. High CpG island methylation of p16 gene and loss of p16 protein expression associate with the development and progression of tetralogy of Fallot. J. Genet. 2016, 95, 831–837.

- Qian, Y.; Xiao, D.; Guo, X.; Chen, H.; Hao, L.; Ma, X.; Huang, G.; Ma, D.; Wang, H. Hypomethylation and decreased expression of BRG1 in the myocardium of patients with congenital heart disease. Birth Defects Res. 2017, 109, 1183–1195.

- Asim, A.; Agarwal, S.; Panigrahi, I.; Saiyed, N.; Bakshi, S. MTHFR promoter hypermethylation may lead to congenital heart defects in Down syndrome. Intractable Rare Dis. Res. 2017, 6, 295–298.

- Yang, X.; Kong, Q.; Li, Z.; Xu, M.; Cai, Z.; Zhao, C. Association between the promoter methylation of the TBX20 gene and tetralogy of fallot. Scand. Cardiovasc. J. 2018, 52, 287–291.

- Gong, J.; Sheng, W.; Ma, D.; Huang, G.; Liu, F. DNA methylation status of TBX20 in patients with tetralogy of Fallot. BMC Med. Genomics 2019, 12, 75.

- Lyu, G.; Zhang, C.; Ling, T.; Liu, R.; Zong, L.; Guan, Y.; Huang, X.; Sun, L.; Zhang, L.; Li, C.; et al. Genome and epigenome analysis of monozygotic twins discordant for congenital heart disease. BMC Genomics 2018, 19, 1–13.

- Dobosz, A.; Grabowska, A.; Bik-Multanowski, M. Hypermethylation of NRG1 gene correlates with the presence of heart defects in Down’s syndrome. J. Genet. 2019, 98, 110.

- Nimura, K.; Ura, K.; Shiratori, H.; Ikawa, M.; Okabe, M.; Schwartz, R.J.; Kaneda, Y. A histone H3 lysine 36 trimethyl-transferase links Nkx2-5 to Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Nature 2009, 460, 287–291.

- Von Elten, K.; Sawyer, T.; Lentz-Kapua, S.; Kanis, A.; Studer, M. A Case of Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome and Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2012, 34, 1244–1246.

- Cooper, H.; Hirschhorn, K. Apparent deletion of short arms of one chromosome (4 or 5) in a child with defects of midline fusion. Mamm. Chromosom. Newsl. 1961, 4, 479–482.

- Zaidi, S.; Choi, M.; Wakimoto, H.; Ma, L.; Jiang, J.; Overton, J.D.; Romano-Adesman, A.; Bjornson, R.D.; Breitbart, R.E.; Brown, K.K.; et al. De novo mutations in histone-modifying genes in congenital heart disease. Nature 2013, 498, 220–223.

- Su, D.; Li, Q.; Guan, L.; Gao, X.; Zhang, H.; Dandan, E.; Zhang, L.; Ma, X. Down-regulation of EBAF in the heart with ventricular septal defects and its regulation by histone acetyltransferase p300 and transcription factors smad2 and cited2. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Basis Dis. 2013, 1832, 2145–2152.

- Robson, A.; Makova, S.Z.; Barish, S.; Zaidi, S.; Mehta, S.; Drozd, J.; Jin, S.C.; Gelb, B.D.; Seidman, C.E.; Chung, W.K.; et al. Histone H2B monoubiquitination regulates heart development via epigenetic control of cilia motility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 14049–14054.

- Guo, T.; Chung, J.H.; Wang, T.; McDonald-McGinn, D.M.; Kates, W.R.; Hawuła, W.; Coleman, K.; Zackai, E.; Emanuel, B.S.; Morrow, B.E. Histone Modifier Genes Alter Conotruncal Heart Phenotypes in 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 97, 869–877.

- Hou, Y.-S.; Wang, J.-Z.; Shi, S.; Han, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhi, J.-X.; Xu, C.; Li, F.-F.; Wang, G.-Y.; Liu, S.-L. Identification of epigenetic factor KAT2B gene variants for possible roles in congenital heart diseases. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40.

- Li, N.; Subrahmanyan, L.; Smith, E.; Yu, X.; Zaidi, S.; Choi, M.; Mane, S.; Nelson-Williams, C.; Bahjati, M.; Kazemi, M.; et al. Mutations in the Histone Modifier PRDM6 Are Associated with Isolated Nonsyndromic Patent Ductus Arteriosus. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016, 98, 1082–1091.

- León, L.E.; Benavides, F.; Espinoza, K.; Vial, C.; Alvarez, P.; Palomares, M.; Lay-Son, G.; Miranda, M.; Repetto, G.M. Partial microduplication in the histone acetyltransferase complex member KANSL1 is associated with congenital heart de-fects in 22q11.2 microdeletion syndrome patients. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1–8.

- Xu, J.; Hu, Z.; Xu, Z.; Gu, H.; Yi, L.; Cao, H.; Chen, J.; Tian, T.; Liang, J.; Lin, Y.; et al. Functional variant in microRNA-196a2 contributes to the susceptibility of congenital heart disease in a Chinese population. Hum. Mutat. 2009, 30, 1231–1236.

- Li, J.; Cao, Y.; Ma, X.-J.; Wang, H.-J.; Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Chen, W.; Wu, Y.; Meng, Y.; Yuan, Y.; et al. Roles of miR-1-1 and miR-181c in ventricular septal defects. Int. J. Cardiol. 2013, 168, 1441–1446.

- Wu, Y.; Ma, X.-J.; Wang, H.-J.; Li, W.-C.; Chen, L.; Ma, D.; Huang, G.-Y. Expression of Cx43-related microRNAs in patients with tetralogy of Fallot. World J. Pediatr. 2013, 10, 138–144.

- Li, D.; Ji, L.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Hou, H.; Yu, K.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, Z. Characterization of Circulating MicroRNA Expression in Patients with a Ventricular Septal Defect. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106318.

- Huang, J.; Li, X.; Li, H.; Su, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhang, H. Down-regulation of microRNA-184 contributes to the development of cyanotic congenital heart diseases. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 14221–14227.

- Wang, Y.; Du, X.; Zhou, Z.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Ye, L.; Hong, H. A gain-of-function ACTC1 3′UTR mutation that introduces a miR-139-5p target site may be associated with a dominant familial atrial septal defect. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25404.

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Song, X.; Liu, L.; Su, G.; Cui, Y. Bioinformatic Analysis of Genes and MicroRNAs Associated With Atrioventricular Septal Defect in Down Syndrome Patients. Int. Heart J. 2016, 57, 490–495.

- Gao, X.; Yang, L.; Luo, H.; Tan, F.; Ma, X.; Lu, C. A Rare Rs139365823 Polymorphism in Pre-miR-138 Is Associated with Risk of Congenital Heart Disease in a Chinese Population. DNA Cell Biol. 2018, 37, 109–116.